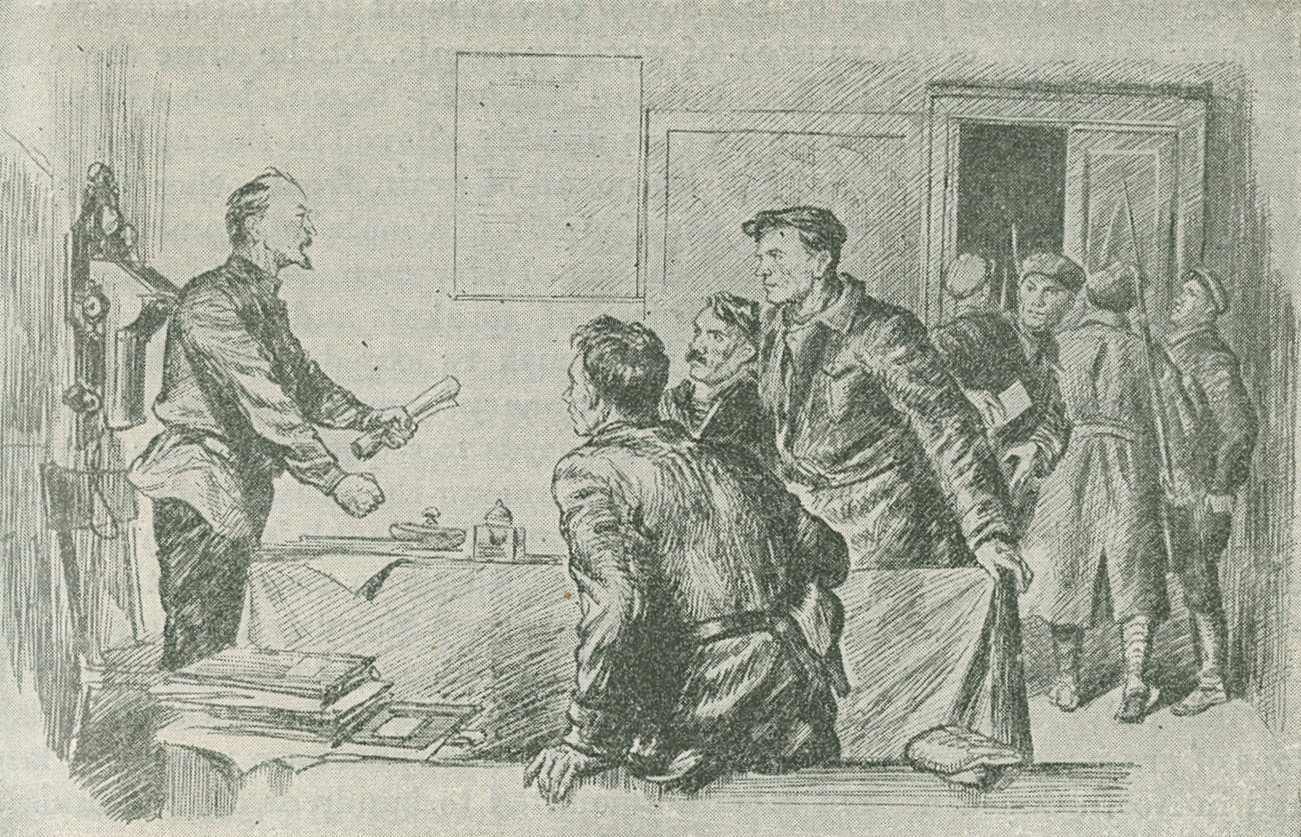

Bonfires were blazing in the square outside the Smolny. At the entrance, Red Guards were scrutinising passes. An endless stream of people flowed into the building. On entering this human flood diverged in two directions, one to the right, to the Military Revolutionary Committee, the other to the left, to the room occupied by the Council of People’s Commissars.

Delegates arrived from distant parts of the country for instructions on how to organise the Soviet administration. Peasants came to receive copies of Lenin’s decree on the land. Delegates from the front arrived to receive copies of the decree on peace. Commanders of detachments left the Military Revolutionary Committee with combat assignments and calling Red Guards out of the darkness of the night, went off to the front.

Long queues were lined up outside the baker shops in the revolutionary capital. The saboteurs wanted to strangle the workers with the gaunt hand of famine, which, in fact, they had deliberately and methodically begun to organise on the eve of the Great Revolution. On October 25, 1917, the stocks of grain in Petrograd were sufficient for only one or two days.

Several days before the October victory of the proletariat the Mensheviks had threatened to resort to the weapon of sabotage in their struggle against the Bolsheviks. Thus, on October 20, the Menshevik A. M. Nikitin, then Minister for the Interior, had said:

“They have no capable forces. Even if they succeed in capturing power we shall refuse to cooperate with them. They will be left isolated.”[1]

On the day the Council of People’s Commissars was formed the Constitutional Democrats, Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries called upon the government officials to refuse to obey the new government. On October 26 the officials of the Petrograd Special Food Department refused to work with the representatives of the Soviet Government and, headed by the Socialist-Revolutionary Dedusenko, they deserted their posts. The officials of the Ministry of Food and of the Petrograd Food Administration went on strike.

The food situation in revolutionary Petrograd was extremely grave. On October 27 there were only 500 tons of grain in the capital, but the starvation ration of less than a half a pound of bread required 800 tons of grain per day. The flour for bread was no longer mixed with barley but with oats. The counter-revolutionary press gloated over the sufferings of the people. The Menshevik Yedinstvo, with the intention of inciting the masses against the Bolsheviks, wrote: “They promised you bread, but they are bringing you starvation.”[2]

All the work of keeping the capital supplied with food was conducted under the direct guidance of Lenin and Stalin. Armed with the right to requisition private stocks, the Bolshevik food officials set to work. Units of Red Guards carefully searched the food warehouses, the barges on the river and freight cars in the railway yards and discovered considerable quantities of grain and flour, which were confiscated. By these means the revolutionary capital obtained an additional supply of 5,000 tons of grain, sufficient for ten days.

The food decrees issued by the Soviet Government stimulated the revolutionary initiative of the masses of working people. At the time the counter-revolutionary forces of Krasnov and Kerensky began their advance on Petrograd the food crisis had been considerably allayed in the capital. Measures were taken to increase the shipment of grain from other districts. In the beginning of November the Council of People’s Commissars sent ten detachments of revolutionary sailors of fifty men each to escort food trains en route to Petrograd. Scores of speakers and Commissars were sent to the rich grain districts of the South to expedite the shipment of grain. Every day the Military Revolutionary Committee formed detachments of revolutionary sailors and Red Guards to requisition grain from the big landlords and to conduct propaganda among the peasants in the grain producing areas to send grain to Petrograd. The People’s Commissariat of Food sent special emissaries all over Soviet Russia to ascertain the whereabouts of food stocks. Some left for Archangel and Murmansk, where, during the war, grain had been shipped abroad. Fifty were sent to Kotlas, where the Northern Dvina meets the Perm-Kotlas Railway. Here, tens of thousands of tons of grain were stored. The stocks of grain in the provinces were very large and in North Caucasus and Siberia amounted to hundreds of thousands of tons.

The provision of grain for Petrograd was greatly hindered by the petty profiteers, or “sack men” as they were called, who swarmed into the grain producing areas and bought grain from the peasants at high prices, thus interfering with government purchases. But the main cause of the food crisis that set in after the great proletarian revolution was the sabotage of the provincial Food Committees, which were controlled by Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik counter-revolutionaries.

The representatives of the revolutionary capital helped the provinces to combat this sabotage on the food front. At the beginning of November the grain reaching the capital did not exceed 15 carloads per day. Hence, notwithstanding the ten days’ stock which had been accumulated by requisitioning, it was found necessary, on November 7, to reduce the daily bread ration to three-eighths of a pound. In the middle of November grain shipments considerably increased, not-withstanding the growing dislocation of the transport system. From November 1 to November 30, 15,277 tons of grain reached Petrograd. By the middle of November 1,200 carloads of grain were under way. In view of that, on November 15, the daily bread ration was increased to half a pound. During the first month of the existence of the Soviet Government the food supply of the capital was quite satisfactory. On November 30 it was decided to increase the bread ration to three-quarters of a pound per day, and to issue an additional pound of flour on every food card. In the middle of November the Petrograd Special Food Department began to issue supplementary food rations for young children.

This considerable improvement in the food supply of the capital was due not only to the increased shipments of grain from outside, but also to a number of measures which had been taken to secure additional stocks in the capital itself, as well as to economy in the expenditure of the available stocks. The criminal saboteurs in various offices had left thousands of tons of food standing in the railway yards. These supplies had to be collected, checked, unloaded and carted into the city. In this matter the Food Administration received considerable assistance from the Military Revolutionary Committee, which, at the beginning of November set up an Unloading Commission vested with extensive powers, including the right to confiscate freights if it deemed necessary. The Commission enlisted the cooperation of the masses in the capital. With their aid it, on November 8, found in the railway goods yard in Petrograd alone, 267 tons of wheat flour, 1,434 tons of wheat, 283 tons of rye flour, 100 tons of rye, 750 tons of fish, over 16 tons of butter, 150 tons of granulated sugar, etc. On November 9, at Navolochnaya Station, on the Nikolayevsky Railway, 5 carloads of grain and 15 tons of sugar were found. The Commission discovered similar stocks every day.

The Commission obtained the voluntary assistance of workers, sailors and soldiers in the difficult task of unloading the freight trains and carting the food supplies to the city. On November 8 several thousand sailors and soldiers were engaged in this work, and all the automobiles and tramcars in the city were mobilised for this purpose. On November 14, about 400 workers were engaged in this work at Navolochnaya Station alone. These were workers from the Obukhov Works, the Pipe Works and other large Petrograd factories who performed this work gratis.

The Bolsheviks called for economy in bread. The Food Administrations vigorously combated the widespread evil of issuing double and treble rations. The private supply of food products to co-operative societies, dining rooms and army units was prohibited. All the restaurants in the city were transformed into public dining rooms, and meals were served only on the presentation of food cards. In its appeal to the working people the Commission of the People’s Commissariat of Food stated:

“Nobody should try to grab for himself more than his comrades and neighbours receive. Let every attempt at food grabbing by individuals or groups, no matter under what pretext, be sternly condemned.”[3]

The Military Revolutionary Committee dealt drastically with food profiteers. In a manifesto it issued to “all loyal citizens” on November 10 it denounced food profiteers as enemies of the people. It called upon the “working people to lodge information of all cases of food pilfering and food profiteering.” “In the prosecution of profiteers and marauders, the Military Revolutionary Committee will be ruthless,” it said.[4] In the middle of November the Council of People’s Commissars adopted the following decision on “Combating Profiteering,” which was published in the press over Lenin’s signature:

“The Council of People’s Commissars orders the Military Revolutionary Committee to take the most determined measures to eradicate profiteering and sabotage, hoarding of food, the malicious holding up of freights, etc. All persons guilty of conduct of this kind are liable to arrest on the warrant of the Military Revolutionary Committee and to confinement in one of the prisons in Kronstadt, pending trial before the Military Revolutionary Tribunal.”[5]

Detachments of Red Guards took profiteers into custody, fined them, and confiscated their stocks. Thus, in the course of combating profiteering and sabotage new revolutionary food administration bodies sprang up. The first measures of the Soviet Government ensured a considerable improvement in the food supply in the capital in November. The counter-revolutionary sabotage of the government officials, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks was broken by the organs of the proletarian dictatorship.

The Socialist-Revolutionaries hastened to the rural districts to organise the kulaks for the purpose of sabotaging the food supply.

The sabotage of the food supply officials was augmented by that of the officials of the Ministries of Finance, Agriculture, the Interior, Ways and Communications, Labour, State Relief, Commerce and Industry, and others. This sabotage was organised. Not only was the privileged upper stratum of the government officials involved, but also the post and telegraph employees, the junior clerks in the government offices, telephone operators and school teachers. The latter categories, though having no economic interest in preserving the capitalist system, nevertheless firmly believed that it was indispensable.

The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks succeeded in convincing the civil servants that the Soviet regime would be shortlived; and so certain were they that the new regime would not last more than two or three days that on leaving their offices they left their sugar ration in their desks as a broad hint that the Bolsheviks would not manage to drink a cup of tea before Kerensky returned. The Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik officials were convinced that running the machinery of state would be the greatest stumbling block to the workers’ rule. In their organ they wrote:

“You may be able to arrest Kerensky and to shoot cadets with artillery; but the best piece of artillery cannot serve as a substitute for even a worn-out typewriter; nor can the bravest sailor take the place of the humblest clerk in any government department.”[6]

The government officials were joined by the officials of the trade unions which were controlled by the Constitutional Democrats and Mensheviks. On the very day the Council of People’s Commissars was formed the Central Committee of the Post and Telegraph Employees’ Union demanded the withdrawal from the union of the Commissars of the Military Revolutionary Committee, threatening to call a strike if this was not done. The Management Board of the All-Russian Union of Credit Institution Employees refused to allow Menzhinsky, the People’s Commissar of Finance, to attend a meeting of the Board on the ground that only the instructions of the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” were valid for it. On October 26, the Menshevik newspaper hastened to sum up the first results of the sabotage in the following terms:

“Only a day has passed since the ‘Bolshevik victory,’ but the Nemesis of history is already on their track. . . . They . . . are simply incapable of grasping political power, it is slipping from their hands . . . they are isolated from everybody, for the entire clerical and technical staff of the state refuses to serve them.”[7]

An important part in organising this sabotage was played by the so-called “Union of Unions,” the federation of civil service employees in Petrograd, which was formed on the initiative of A. M. Kondratyev, N. I. Kharkovtsev, M. I. Lappo-Starzhenetsky and other high, pro-Constitutional Democratic officials, and which was controlled by the privileged upper stratum of the government officials in Petrograd. The first step towards forming the federation was taken in July 1917, but it did not assume definite shape until the eve of the October Revolution. Immediately after the proletarian revolution, the “Union of Unions” established contact with the counter-revolutionary “Committee for the Salvation”—the shadow Provisional Government—and the strike committees of the various Ministries, and undertook the leadership of the sabotage of the officials of those Ministries.

Another important sabotage organisation, which was connected with the “Union of Unions,” was the so-called “Soviet of Working Intelligentsia Deputies,” which was formed in May 1917 and consisted of representatives of the bourgeois, pro-Kornilov intellectuals. This Soviet had 29 representatives on the Moscow Council of State. Like the “Union of Unions,” it was led by Constitutional Democrats, and most of its members were of the same political persuasion. Together with organisations such as the Physicians, Engineers, and Agricultural Workers’ Unions, the “Soviet of Working Intelligentsia Deputies” maintained communication with “intellectual” organisations like the Union of Cossack Forces, and with anti-Soviet organisations like the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Officers’ Deputies and the Manufacturers’ Association.[8] The “Working Intelligentsia” issued a daily bulletin for distribution among the striking government officials in which it repeated the slander liberally culled from the columns of Rech, Volya Naroda, Dyelo Naroda, Petrogradskaya Gazeta, and other counter-revolutionary rags. The following is an example of the tirades indulged in by this “intellectual” Soviet:

“The impending danger is not only of a political but also of a material nature. The salaries of workers engaged in intellectual pursuits will often depend on the caprice of doorkeepers.”[9]

But the “doorkeepers” courageously opposed the sabotage. Thus, Gerasim Ogur, a doorkeeper at the Volga-Kama Bank in Petrograd, refused to join the saboteurs, and to help the Red Guards take control he brought his daughter Maria, a schoolteacher, to the bank. The saboteurs proclaimed a boycott against Gerasim and his daughter. Their names were entered in a “black list” and posted on the doors of the bank; but they refused to be intimidated and continued at their work.

In nearly all the Ministries the junior staffs willingly expressed their readiness to help the workers and Red Guards to build up the new administration. In many cases it turned out that men who for decades had been employed in government offices merely as messengers could be utilised for responsible work. Thus, in spite of the intimidation of the saboteurs, ten members of the Special Credit Department staff of the Ministry of Finance volunteered for work at the People’s Commissariat of Finance. Eight of these had formerly been messengers. In the same Ministry, the messengers informed the Commissar of the members of the staff who were in sorest need and who could be won away from the saboteurs.

The saboteurs at the banks and at the Ministry of Finance believed that as a result of their strike the factory workers would not receive their wages and that this would give rise to hunger riots. This is exactly what I. P. Shipov, the Director of the State Bank, an old bureaucrat, Durnovo’s placeman and colleague of Stolypin the Hangman and of Stürmer, was driving at. But about a thousand members of the junior staff of the State Bank continued at work in spite of all the efforts of the saboteurs to intimidate them, and wages were paid on time. Soldiers and sailors who had formerly been employed in government offices arrived from the front, took the places of the saboteurs and, side by side with the workers, helped to build up the new edifice of state. The more democratic section of the government officials also opposed the saboteurs.

The Constitutional Democratic Party was the chief inspirer of the counter-revolutionary saboteurs, and the leaders of this party, Kutler, Hessen, Khrushchev, Kiesewetter, and others, were at the head of the sabotage organisations. During these days, Lappo-Starzhenetsky, a high official, an engineer by profession, and one of the most active members of the Constitutional Democratic Party, hurried from one Ministry to another forming strike committees and giving directions to the sabotage leaders. Before the government officials he posed as a champion of democracy. “Why must we strike?”—he asked the awe-struck officials who were not accustomed to receive such gracious attention or to hear such “democratic” speeches from the high and mighty bureaucrats. Because, he said, “Soviet decrees mean loss of freedom and uncontrolled tyranny.”[10] The officials were rather hazy about the point as to who were losing their freedom and whose control the Bolsheviks were overthrowing but they voted in favour of a strike because they were convinced that the Bolsheviks could not remain in power long, and this conviction was reinforced by the six weeks’ or two months’ salary in advance which they received from the sabotage leaders.

The sabotage leaders were closely connected with the biggest capitalist organisations in the country and received financial assistance from them for the sabotage movement. Lappo-Starzhenetsky himself was connected with the firm of Ericson, with M. Ferrand, the representative of French trading companies, with the United Cable Works, Ltd., Siemens-Schuckert, and other firms.[11] The saboteurs also received financial assistance from the commercial house of Ivan Stakheyev in Moscow, from the Caucasian Bank, the Tula Land Bank, the Moscow People’s Bank, and from a number of private individuals with interests in large-scale industry and commerce.

These capitalists donated large sums of money for the purpose of the strike, for they were aware that the very existence of the landlord and capitalist administration was at stake. According to the evidence of the ex-Vice-Minister of Justice, Demyanov, the members of the deposed Provisional Government drew 40,000,000 rubles from the State Bank and financed the sabotage movement with the money. The sabotage committee of the private bank employees collected 2,000,000 rubles for a strike fund for the government officials and of this money L. Tessler, the chairman of this committee, transferred to A. M. Kondratyev, the chairman of the “Union of Unions,” 1,500,000 rubles.[12] The saboteurs also received assistance from the French Mission through the Russo-Asiatic Bank and other banks.[13] Members of this committee also collected money by means of subscription lists, and L. V. Urusov, one of the leaders of the “Union of Unions” and formerly on the staff of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, collected a fairly large sum in this way. The sabotage leaders carefully concealed from the masses of the civil servants the sources from which they obtained their funds. Thus, at the Congress of Postal Employees one of the delegates asked from what sources 200,000 rubles were paid out to the employees of the Ministry of Post and Telegraph, but the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik leaders declined to answer the question.

The struggle against the proletarian dictatorship assumed other forms besides open sabotage. The old bourgeois state administration tried to adapt itself to the new conditions and thus insure itself against complete demolition. This was particularly the case with the very part of the administration which was due to be broken up in the first place, immediately. Thus, at a meeting of the central strike committee, the representative of the “Judges’ Union” argued that an exception should be made in their case, that they should be permitted to continue to function in spite of the Bolsheviks’ order to dissolve. “The courts must not go on strike,” he said. “If they do, self-appointed tribunals will arise.”[14] And these tactics were fully approved by the strike committee. The officials were aware that their sabotage would not only hasten the break up of the old state administration, but also stimulate the initiative of the masses in building up new organs of government. “Self-appointed” tribunals were already springing up.

The officials of the Ministry of the Royal Household were also reluctant to go on strike. When the Chancellery of this Ministry was abolished, Prince Gagarin, the Director of the Chancellery, and Baron von der Stackelberg, the Vice-Director, came to Lunacharsky to lodge a protest against this. “We are drawing up memoranda for the Minister, we do not intend to strike and we ought not to be dissolved,” they said.[15] The protest of the Baron and the Prince were of no avail. The Chancellery was abolished. It was evident, however, that the officials were banking on retaining their old staffs and preserving the old state administration.

The Kerensky government had left the old tsarist administration entirely intact with all its trimmings. For example: when Lunacharsky and the officials of the People’s Commissariat of Education came to the Winter Palace, they were met by a footman in grey livery, who, in an ingratiating whisper, invited them to take lunch. In the ex-tsar’s dining room they found the table loaded with the choicest viands. Famine was rampant in Petrograd, the workers were without bread, but here, everything went on as before. The Hofmarschall had at his command a vast staff of footmen and other servants. Under Kerensky, this was retained. Had the tsar returned he would have found his household in perfect order, and there would have been no need for him to change his habits of life in the slightest degree.

The bureaucracy of the tsarist and Provisional Governments urged the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks to preserve the old state administration, but the more democratic section of the administration, the junior officials of the different Ministries, saw through the tactics of the higher bureaucracy. The reactionary trade union bureaucracy also made an attempt to save the old administration and to forestall the Soviet Government. Thus, when all its efforts to form a new government had come to naught, the Railwaymen’s Executive tried to seize control of the Ministry for Ways and Communications. On the instigation of the “Committee for the Salvation” the Post and Telegraph Employees’ Union tried to seize control of the Ministry of Post and Telegraph.

These attempts failed, however, and this induced the saboteurs to pass from passive resistance to active sabotage. They ostensibly abandoned their strike and returned to work, but they did all in their power to discredit the new administration. In the State Bank, for example, the officials deliberately mixed up all the books and accounts. Even in the office of the City Directory, the officials mixed up the address files and created utter chaos. These new tactics of the saboteurs were exposed in December 1917 by a group of employees at the People’s Commissariat of Labour, in the following terms:

“The sabotage of these false friends of the people—whose tactics are to attend meetings, take part in debates and pour cold water on every project, to intimidate everybody and to prevent any results from being achieved in order to be able to say to the masses that so much time has passed and yet the Bolsheviks have achieved nothing and have fooled the people—such sabotage must be overcome by means of unremitting practical activity.”[16]

The sabotaging officials received financial assistance also from the old All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets and from the underground Provisional Government. The old Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik All-Russian Central Executive Committee continued to meet secretly even after the Second Congress of Soviets. Among those who attended these secret meetings were I. G. Tsereteli, Abramovich, Dan, Broido and Weinstein. Some of the members took refuge at General Headquarters in Moghilev and tried to continue their activities there. In Petrograd a bureau of 25 was set up. With the funds which the old All-Russian Executive Committee should have transferred to its legal successor elected at the Second Congress of Soviets, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks organised sabotage and assisted the “Committee for the Salvation.” The salaries of the staff of this “Committee” were paid by the old All-Russian Central Executive Committee. The latter even tried to issue a newspaper, but the workers at the printshop refused to set it up or print it. This obsolete body dragged out a miserable existence. At its meetings the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks discussed such trivial matters as ways and means of obtaining automobiles from the Central Executive Committee’s garage, how to get free box tickets for the theatre, and so forth.

The deposed Provisional Government also tried to extend its existence beyond the span allotted to it by history. Six ex-Ministers and twenty-one ex-Vice-Ministers formed themselves into a so-called government, which met at various intervals between November 6 and 16, its composition different every time it met. Among those who attended these meetings were the ex-Ministers Nikitin, Malyantovich, Liverovsky, Gvozdev and Prokopovich, and several ex-Vice-Ministers and permanent secretaries. A “government” of such a composition lacked validity even according to bourgeois standards of legality. Describing this underground “government,” one of the meetings of which he had attended, V. D. Nabokov wrote:

“We had the customary unbearably long-winded interminable speeches, which nobody listened to. The prevailing mood was appalling, and that of some of them, particularly Gvozdev, was simply panicky. The only concrete method of fighting discussed was, I think, a strike of the officials.”[17]

“This was no longer life, but mere existence, and a rather shameful existence at that,” wrote A. Demyanov, the ex-Vice-Minister of Justice, in his memoirs.[18]

[1] “Interview with A. M. Nikitin,” Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, No. 202, October 20, 1917.

[2] “They Promised Bread But Are Actually Leading to Famine,” Yedinstvo, No. 178, November 3, 1917.

[3] “From the Food Commission,” Pravda, No. 195, November 21, 1917.

[4] “To All True Citizens,” Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee and of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, No. 224, November 13, 1917.

[5] Compendium of Legislative Acts and Orders for the Workers’ and Peasants’ Government, No. 3, December 8, 1917, p. 38.

[6] Tribuna Gosudarstvennikh Sluzhashchikh, (The State Employees’ Tribune), 1917, No. 19, p. 3.

[7] “Without Power,” Rabochaya Gazeta, No. 198, October 28, 1917.

[8] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 314, folios 41-44.

[9] Ibid., File No. 114, folio 13.

[10] Ibid., File No. 233, folio 3.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., File No. 228, Vol. II, folio 30.

[13] Ibid., folio 39.

[14] Ibid., folio 45 (7).

[15] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of the “H.C.W.”

[16] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 130, Roll B, Catalogue No. 6, File No. 6, folio 45.

[17] V. Nabokov, Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. IV, Berlin, 1922, p. 91.

[18] Ibid., p. 120.

Previous: The Rout of the Defeatist Bloc

Next: The Amalgamation of the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies