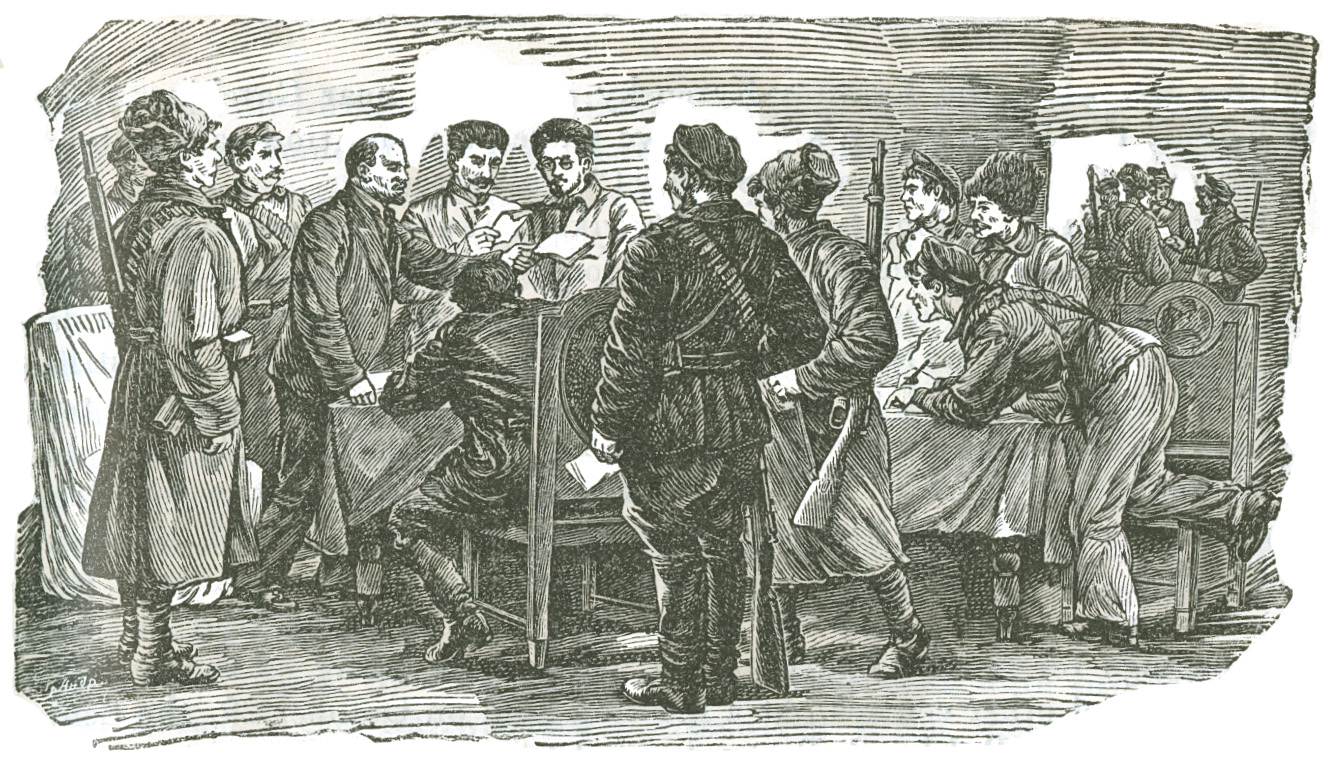

he harbingers of the insurrection—the delegates at the Second Congress of Soviets—dispersed to their respective localities. The Smolny Institute—the Staff Headquarters of the revolution—was connected with every part of the country. The “Smolny period” commenced. In the initial stage of the proletarian dictatorship the Smolny was the hub of the seething activities of the Bolsheviks—the builders of the new state administration.

he harbingers of the insurrection—the delegates at the Second Congress of Soviets—dispersed to their respective localities. The Smolny Institute—the Staff Headquarters of the revolution—was connected with every part of the country. The “Smolny period” commenced. In the initial stage of the proletarian dictatorship the Smolny was the hub of the seething activities of the Bolsheviks—the builders of the new state administration.

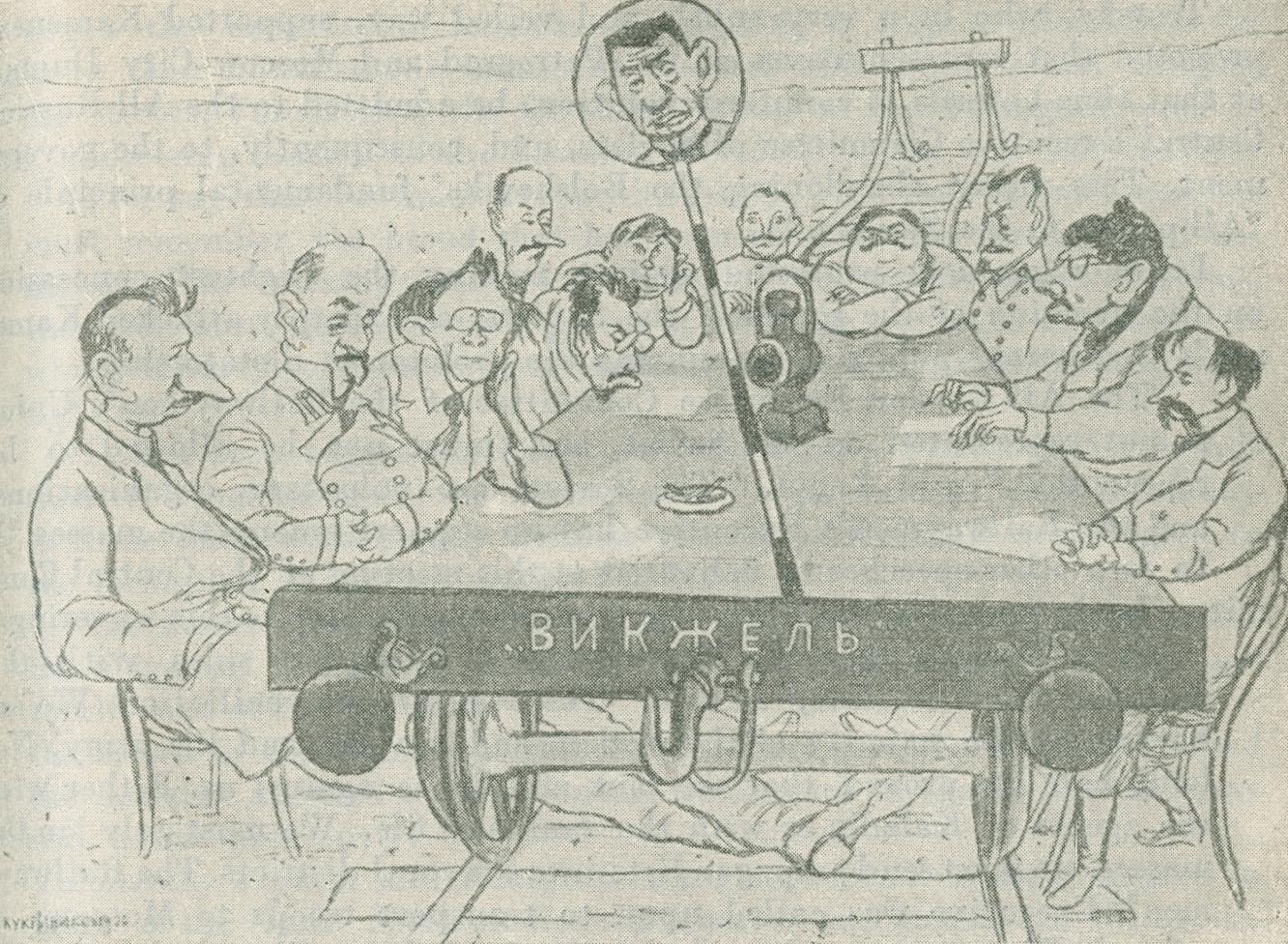

The enemy had not yet been routed. Kerensky was drawing troops to the revolutionary capital; the cadets had risen in revolt; in Moscow a fierce struggle for power was raging. But while the fate of the revolution was being decided by force of arms near Pulkovo and in the streets of Moscow, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks attempted to disrupt the revolution from within and for this purpose transferred their activities to the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Railwaymen’s Union. On October 29, when the Krasnov-Kerensky offensive near Gatchina was at its height, the Railwaymen’s Executive passed a resolution calling for the formation of a homogeneous “Socialist” government.

It was clearly evident to the Bolsheviks that the Railwaymen’s Executive, issuing its statement at the very moment when the political question was “on the verge of becoming a military question,”[1] was on the side of the Kornilovs and Kaledins. Its demand for the cessation of hostilities when all that remained to be done was to give the finishing stroke to the Kerensky affair, was downright support for the counter-revolution.

Sailing under “neutral” colours, the Railwaymen’s Executive could carry some of the wavering railwaymen in its wake. Moreover, it had the railway administration at its disposal. Something had to be done to render it harmless, to prevent the transportation of Kerensky’s troops, and to secure free passage for revolutionary troops which were going to the assistance of Moscow and other centres. At a meeting held on October 29, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party decided to send representatives to negotiate with the Railwaymen’s Executive. As Lenin put it, these negotiations were to act as a diplomatic screen for military operations. On the question of changing the composition of the government the Central Committee advanced the following as the main conditions for negotiations: that the government should be responsible to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets; recognition of the Second Congress of Soviets as the sole seat of power, and endorsement of the decrees on land and peace.

The initial meetings of the Railwaymen’s Executive’s “Commission for Drafting an Agreement between the Parties and Organisations” were held on October 29 and 30 and were attended by prominent representatives of the various Menshevik and Socialist-Revolutionary groups and coteries.[2] Among them were the Menshevik defencists Dan and Erlich, the Internationalist Mensheviks Martov and Martynov, the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries Malkin and Kolegayev, and the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries Jacobin and Hendelmann. In addition to representatives of the “Committee for the Salvation” there was also present one of the organisers of the sabotage movement against the Soviet Government by the civil servants, viz., A. Kondratyev. Officially, he represented the Clerks’ Union. Representatives were also present from the All-Russian Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies, the Government Office Employees’ Union, and other organisations.

The political stand taken by these meetings was predetermined by the views of those attending them. In different keys, perhaps, some more and some less openly, both the Right and the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks demanded one and the same thing, viz., the liquidation of the revolution. At the session held on October 29, Hendelmann, representing the Central Committee of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, reminded the Railwaymen’s Executive that it was “throwing the last weight in the scales of the contending groups” and demanded the liquidation of the “adventure” and the formation of a Ministry without the Bolsheviks. The “Leftist” Martov demanded the organisation of a government “that would rely on the democratically organised elements, not only the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, but also bodies which had sprung up under universal suffrage.”[3] Dan was more candid. He said:

“The first condition of agreement is: liquidation of the conspiracy; dissolution of the Military Revolutionary Committee; the Congress [the Second Congress of Soviets—Ed.] be declared invalid. . . . If this condition is carried out we shall unite our efforts to combat the impending counter-revolution.”[4]

This session ended with the election of a committee to draw up proposals regarding the composition of the government and the measures to be taken to avert civil war.

Late that night, in view of the negotiations that were proceeding for an “armistice,” the Railwaymen’s Executive wired instructions to call off the railway strike which had started, but insisting, however, that the strike committees should not be dissolved, but remain in “full preparedness.”

Early in the morning of October 30, the so-called “Special Commission for Drafting an Agreement between the Parties and Organisations” met. Dan, Weinstein, Posnikov, Kamenev, Ryazanov and others were present. Dan addressed the Commission on behalf of the “Committee for the Salvation” and enumerated the demands that were to be presented to the Bolsheviks. These were:

“To disarm the workers and offer no resistance to Kerensky’s troops. To place the troops at the disposal of the City Duma. To release the arrested members of the government. . . .”[5]

“The workers must abandon the idea of engaging in battle with the troops,” he stormed. “Every Social-Democrat must insist on this, for it is impossible for the proletariat to resist the bourgeois troops.”[6]

Dan was supported by Weinstein. The Mensheviks were already gloating in anticipation of the sweets of victory. They imagined that they were in a position to dictate their terms, for Kerensky’s troops were expected to enter Petrograd at any moment.

Dan and Weinstein were followed by Kamenev who treacherously withheld from the Commission the terms the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party had laid down in its decision of October 29 for changing the composition of the government. This blackleg believed that the opportune moment had arrived to liquidate the proletarian insurrection. He proposed that an appeal be issued to the proletariat and to the troops to. . . disarm!

At 11 a.m. a joint meeting of the Railwaymen’s Executive and representatives of the different political parties was held. By this time the delegation of the Railwaymen’s Executive which had gone to see Kerensky had returned to Petrograd and at this meeting it reported the results of its negotiations. Planson, the representative of the Railwaymen’s Executive, was obliged to admit that:

“Discipline in Kerensky’s camp is below that in the Petrograd camp, where the workers stand shoulder to shoulder with the soldiers.”[7]

On learning that hostilities had commenced at Pulkovo the Railwaymen’s Executive began in the most obvious manner to drag out the negotiations. At one moment Dan threatened the workers of Petrograd with dire punishment and at another promised to plead with Kerensky “to refrain from violence and repression on entering the city.” It was decided to adjourn the meeting until the evening, by which time, it was expected, Kerensky would have defeated the revolutionary troops near Pulkovo.

But on October 30 Kerensky’s troops sustained utter defeat near Pulkovo. The hopes of the Railwaymen’s Executive that the Kerensky-Krasnov forces would enter the revolutionary capital were dashed to the ground. The joint meeting was resumed for the third time that day. The counter-revolutionaries tightly clung to the Railwaymen’s Executive in the hope of being able to smash the Bolshevik government with the aid of blacklegs of the type of Kamenev. At this evening session Kamenev spoke again. He tried to cheer up the despondent Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks and repeated, word for word, the statement he had made in the morning that it was necessary to form a new government. The meeting adopted the following decision:

“Immediately to conclude an armistice and to issue an appeal to both contending sides to cease hostilities.”[8]

At night on November 1, the Railwaymen’s Executive Commission met again in the premises of the Ministry for Ways and Communications and sat all night discussing the composition of a “Provisional People’s Council” to which the government was to be responsible. At this meeting Kamenev, Sokolnikov and Ryazanov treacherously violated the implicit instructions they had received from the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party to the effect that the government was to be responsible only to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee which was elected at the Second Congress of Soviets. Ignoring this decision, Kamenev, Ryazanov and Sokolnikov gave their consent to the formation of another Pre-parliament. Encouraged by Kamenev’s compliance, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks strenuously objected to the inclusion of Lenin in the proposed government.

Kamenev and Sokolnikov not only took part in the discussion of this question, but even failed to insist on Lenin’s inclusion in the government. Together with Ryazanov, they participated in the discussion of the candidatures of Chernov and Avksentyev for the post of . . . Prime Minister! The meeting came to a close just before dawn. At the end of the meeting, Kamenev assured the Railwaymen’s Executive that the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies would agree to the terms it had drafted and promised to take measures to secure the cessation of hostilities on the Petrograd Front. An undertaking of this kind just when the counter-revolutionary forces were being routed near Pulkovo was tantamount to direct assistance to Kerensky and Krasnov, who would have been glad of an armistice in order to save their forces and recuperate.

On November 1, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party discussed Kamenev’s conduct at the conference with the Railwaymen’s Executive.

“. . . Kamenev’s policy must be stopped,” said Lenin. “There is now no point in negotiating with the Railwaymen’s Executive.”[9]

Dzerzhinsky sharply attacked Kamenev and accused him and Sokolnikov of having failed to carry out the instructions of the Central Committee. He moved a vote of no confidence in them, and suggested that they should be replaced by other members of the Central Committee.

Kamenev, in his duplicity, withheld from the Central Committee the fact that he had promised the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks that the Petrograd Red Guards would be disarmed. He also tried to conceal from the Central Committee that the question of keeping Lenin out of the government had been discussed only a few hours previously. “The delegation did not discuss nominations,” he said mendaciously.

Trotsky, who in a very subtle and veiled way, supported Kamenev, proposed that representatives of the Petrograd and Moscow City Dumas, at that time hotbeds of counter-revolution, be admitted to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets, and, consequently, to the government. This meant abandoning the Bolsheviks’ fundamental principle of “All power to the Soviets.”

Lenin vigorously protested against making the slightest concession on the question of the power of the Soviets, and sharply attacked Kamenev’s treacherous policy of renouncing the proletarian dictatorship.

“The All-Russian Executive Committee of the Railwaymen’s Union is not represented on the Soviet, and must not be allowed to be represented,” said Lenin. “The Soviets are voluntary organisations, and the Railwaymen’s Executive has no support among the masses.”[10]

In two other speeches he delivered at this meeting of the Central Committee Lenin demanded that “the waverers must put a stop to this wavering.”

“It is obvious that the Railwaymen’s Executive sides with the Kaledins and Kornilovs,” he said. “There must be no vacillation. We are backed by the majority of the workers and peasants and the army. Nobody here has proved that the rank and file is against us. Either with the agents of Kaledin or with the rank and file. We must rely on the masses, we must send propagandists into the rural districts. The Railwaymen’s Executive was called upon to transport troops to Moscow; it refused. We must appeal to the masses, and they will overthrow it.”[11]

At this meeting the Central Committee adopted the following resolution:

“Whereas the experience of preceding negotiations has shown that the compromising parties conducted these negotiations not with the object of forming a united Soviet Government, but with the object of causing a split among the workers and soldiers, of disrupting the Soviet Government and of finally tying the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries to the policy of compromise with the bourgeoisie, the Central Committee resolves: in view of the decision already adopted by the Central Executive Committee, to permit members of our Party to participate in the last effort to be made today by the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries to secure the formation of a so-called homogeneous government with the object of finally exposing the hopelessness of this attempt and of putting a stop to all further negotiations for the formation of a coalition government.”[12]

The Central Committee drew up the following terms for the negotiations: recognition of the decrees of the Second Congress of Soviets; relentless struggle against the counter-revolution, and recognition of the Second Congress of Soviets as the sole seat of power.

On the night of November 1, Ryazanov reported to a meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets the results of the deliberations of the Railwaymen’s Executive Commission. Again and again Krushinsky, on behalf of the Railwaymen’s Executive, and Kamkov, on behalf of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, got up and vehemently urged the necessity of immediately putting a stop to bloodshed. In reply to their howls about imminent disaster and about blood flowing in the streets, Volodarsky, the favourite orator of the Petrograd workers said, addressing himself to the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks:

“You say that we must avoid bloodshed. Yes, that is true. But we must remember the blood that has been shed for the fundamental demands of the working class and the peasantry. If you are afraid of blood, then you must do all in your power to hold the positions in defence of which hundreds of thousands of workers, peasants and soldiers have been fighting.

“It has been suggested that we should form a Provisional People’s Council—something in the nature of a Pre-parliament; and this body is to be built without any definite principle. We shall never agree to the formation of another mongrel body.

“The insurrection of the workers and soldiers was accomplished under the slogan of ‘All power to the Soviets!’ Concessions on this point are totally out of the question.”[13]

On behalf of the Bolshevik group Volodarsky moved a resolution based on the decision adopted by the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party several hours previously.

Volodarsky’s plain and straightforward statements caused dismay in the ranks of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and Menshevik Unionists. V. A. Bazarov got up and said that the blame for prolonging the civil war would rest on the Bolsheviks, and adhering to his policy of a bloc with Kamenev, Ryazanov and others, he stated that the resolution proposed by Volodarsky ran counter to and violated the principles which Kamenev, Sokolnikov and Ryazanov had accepted at the meeting of the Railwaymen’s Executive Commission.

Karelin stated that the Bolsheviks’ resolution did not satisfy the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary group because it contained much that was categorical and formally uncompromising. On behalf of his group Karelin read a resolution in which it was proposed that a “Convention” of 275 members be formed. In this “Convention” the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets was to have 150 seats, the City Dumas 50 seats, the Gubernia Peasants’ Soviets 50 seats, and the All-Russian Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies 25 seats. The resolution also recognised the necessity of accepting the decrees of the Second Congress of Soviets as the basis of the activities of the proposed Convention.

Karelin’s tactics fully coincided with Trotsky’s. For the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries as well as for Trotsky the important thing was not so much the recognition of the program of the Second Congress of Soviets as the changing of the composition of the governing bodies, the abandonment of the Soviet power. Programs can always be renounced, they held.

On a vote by roll call the Bolshevik resolution polled 38 votes and that of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries 29. Disconcerted by this result the Socialist-Revolutionaries begged for an adjournment. They were in a serious predicament. By voting against the Bolshevik resolution the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries put themselves in danger of becoming isolated from the masses. Fearing isolation and the loss of all influence, they renounced their own resolution. An hour later, when the session was resumed, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee unanimously adopted the resolution moved by Volodarsky.

Meanwhile, the rift among the petty-bourgeois parties became wider. The leaders of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries were not at all sure that the rank-and-file members of their party would support them in the struggle they had started against the Council of People’s Commissars. Their fears were fully warranted. A conference of Petrograd “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries which was held on November 1 called upon the members of their party unreservedly to submit to the Council of People’s Commissars and to cooperate with the Military Revolutionary Committee. In retaliation, the Central Committee of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party dissolved the Petrograd organisation of that party.

Uncertain of the support of their rank and file, the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries hastened to cement their bloc with the Kamenevites. Karelin openly expressed the hope that the latter would within the next few days vote with the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and thus form the majority on the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. The defeat of Kerensky accelerated joint action on the part of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and Right defeatists on the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.

On November 2, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party adopted a decision on the negotiations with the Railwaymen’s Executive. By that time the situation had undergone a marked change. Kerensky was utterly defeated. In Moscow the revolutionary troops were capturing position after position. In these circumstances, the Central Committee, on Lenin’s motion, passed a resolution which, reaffirming the Central Committee’s previous decision concerning an agreement, still more strongly denounced the huckstering of the Railwaymen’s Executive. The resolution stated:

“. . . without betraying the slogan of the power of the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies there can be no entering into petty bargaining with the object of admitting into the Soviets organisations of non-Soviet type, i.e., organisations which are not voluntary associations of the revolutionary vanguard of the masses who are fighting for the overthrow of the landlords and capitalists.

“. . . The Central Committee affirms that to yield to the ultimatums and threats of the minority on the Soviets would be tantamount to complete renunciation not only of the Soviet power but of democracy, for such yielding would mean that the majority fears to make use of its majority, it would mean submitting to anarchy and inviting the repetition of ultimatums on the part of any minority.”[14]

The last point in Lenin’s resolution affirmed the possibility of the victory of Socialism in Russia and indicated the conditions that would ensure this victory. This point read as follows:

“. . . despite all difficulties, the victory of Socialism both in Russia and in Europe, can be ensured, but only by the unswerving continuation of the policy of the present government. The Central Committee expresses its firm belief in the victory of this Socialist revolution, and calls upon all sceptics and waverers to abandon their waverings and whole-heartedly and with supreme energy to support the actions of this government.”[15]

This resolution was a condemnation of the policy of Kamenev and Zinoviev, which was based on the assumption that Socialism could not triumph in one country alone. Lenin’s resolution was adopted in opposition to the votes of Kamenev, Zinoviev, Rykov, Nogin and Milyutin. These Right defeatists left the meeting of the Central Committee determined to secure the latter’s defeat at the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets.

Late at night on November 2, at the meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, Malkin, on behalf of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary group, categorically demanded that the question of the platform for an agreement between the Socialist parties be reconsidered. Malkin was followed by Zinoviev. This traitor to the proletarian revolution resorted to a well-tried method employed in bourgeois parliamentarism, viz., that of setting up the parliamentary group against the Party as a whole. He read the resolution adopted by the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party on the question of agreement with the other Socialist parties and immediately went on to say that the Bolshevik group on the Central Executive Committee had not yet discussed it.

The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks readily agreed to Zinoviev’s motion to adjourn for an hour to enable the groups to discuss the resolution. After this “discussion” Kamenev, in the name of the Bolshevik group, moved another resolution, which was in glaring contradiction to that adopted by the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party. Kamenev’s resolution called for the continuation of the negotiations concerning the government with all the parties affiliated to the Soviets, with the proviso that not less than half the seats in the government should be granted to the Bolsheviks. Hence, the other half was to be taken by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. It also proposed that the All-Russian Central Executive Committee be enlarged by the inclusion of representatives of the Railwaymen’s Executive, the Peasants’ Soviets and the army, but it did not stipulate that new elections of these Soviets and committees were to be held. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries welcomed Kamenev’s resolution.

“The Bolsheviks’ resolution is a step in the direction of agreement. Consequently we shall vote for it,” said Karelin.[16]

The interests of the revolution, of the as yet incomplete insurrection, called for the immediate rout of the Right defeatists. The compromising fuss and bustle of the handful of Kamenevites and “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries had to be opposed by the firm line of the proletarian dictatorship. The meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee at which Kamenev and Zinoviev had so shamefully and treacherously acted contrary to the decisions of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party ended in the small hours of November 3. As soon as Lenin heard of this latest act of disloyalty he drew up an ultimatum to be presented to Kamenev and Zinoviev in the name of the majority of the Central Committee and sent a copy of it to each member of the Central Committee separately with a request that each append his signature. In this ultimatum Lenin denounced the defeatists and in categorical terms demanded strict adherence to Party discipline and the execution of Party decisions.

Having once taken the path of fighting the Bolshevik Party and of compromising with the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks, this group of defeatists proceeded further, accompanied by the plaudits of the petty-bourgeois parties.

Meanwhile, in the lobbies of the Railwaymen’s Executive, the most unscrupulous bargaining was going on around the question of the composition of the so-called “Provisional People’s Council.” On November 3, the Railwaymen’s Executive Commission met again. This time the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party appointed Stalin as their representative. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks sent their leaders to the meeting with the intention of accomplishing what they had failed to accomplish by force of arms near Pulkovo. Among these leaders were the Mensheviks Abramovich, Martov, Yermansky, Martynov, Rosental and Stroyev, and the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries Karelin, Schreider, Spiro, Proshyan, and others. The treacherous policy of Kamenev and Zinoviev had emboldened the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik leaders. Abramovich and Martov furiously attacked the Council of People’s Commissars.

“Oceans of fraternal blood,” shouted Abramovich. “There is no government in Russia. . . . Newspapers are not appearing. . . . Martial law. . . .”[17]

On behalf of the Menshevik Central Committee Abramovich moved a resolution which stated:

“Neither the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks, nor its transfer to the Soviets can be recognised by the other sections of democracy under any circumstances.”[18]

Martov vehemently denounced the reign of terror and the arrest of Railwaymen’s Committees. He forgot to add, however, that the Railwaymen’s Executive was itself arresting railwaymen who were demanding active struggle against the counter-revolution.

When Martov, Abramovich and others demanded guarantees for the cessation of terror, Stalin got up and, addressing Abramovich, asked him in a tone of irony:

“Can anybody guarantee that the troops which are disposed near Gatchina will refrain from attacking Petrograd?”[19]

This meeting proved abortive. Next day, November 4, a meeting of the All-Russian Central Committee was held, at which the Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Mensheviks and the Kamenevites launched a united attack. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries were already talking openly about their bloc with the Kamenevites. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary, Malkin, gleefully shouted that Lenin was in “splendid isolation”[20]; and Karelin blurted out his most cherished thoughts when he said:

“The moderate Bolsheviks will influence the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Petrograd Soviet.”[21]

Meanwhile, Bukharin was negotiating with the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries for joint action against the Council of People’s Commissars with the object of restoring the capitalist system and of organising the assassination of the leaders of the revolution—Lenin, Stalin and Sverdlov.

The initiative in the attack on the Council of People’s Commissars now passed to the Right defeatists who were loudly applauded by the Socialist Revolutionaries. The first to address the meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee on November 4 was Larin. He moved the rescindment of the decree of the Council of People’s Commissars on the press; and without singling out the question of the press “from the other restrictions imposed by the revolutionary government,”[22] he, in the same breath, proposed that a tribunal be set up with the right to examine all cases of arrest, suppression of newspapers, and so forth. This was in effect an open declaration of no confidence in the Council of People’s Commissars. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries lost no time in supporting Larin’s proposal.

All this “democratic” pother around the decree on the press, however, was part and parcel of the general offensive which had been launched against the proletarian dictatorship. Krasnov, the cadets and the Whiteguards fought openly with arms in hand, while the Railwaymen’s Executive, the Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Mensheviks and the Right defeatists acted as saboteurs and disrupters in the rear. The Zinoviev and Kamenev group joined this united front of the counter-revolution. Replying to these alleged champions of “freedom of the press,” Lenin said:

“A miserable handful has started civil war. It is not ended yet. The Kaledinites are approaching Moscow and the shock battalions are approaching Petrograd. . . .

“We are quite ready to believe that the Socialist-Revolutionaries are sincere; nevertheless behind them are Kaledin and Milyukov.

“The firmer you soldiers and workers are, the more we shall achieve. If we are not firm we shall be told: ‘They cannot be strong yet if they are releasing Milyukov.’ We announced beforehand that we would suppress the bourgeois newspapers when we took power. To have tolerated the existence of such newspapers would have meant ceasing to be a Socialist. . . .

“What freedom do these newspapers want? Freedom to buy huge quantities of paper and an army of hacks? We must deny freedom to a press which is dependent on capital. . . . Since we are marching towards the social revolution we cannot allow Kaledin’s bombs to be supplemented by bombs of falsehood.”[23]

The workers and soldiers had already learned what this “freedom of the press” meant. Day after day the counter-revolutionary newspapers released a flood of the filthiest lies and slander against them. The Red Guards were accused of raping the members of the women shock battalions, although the women themselves wrote from the Fortress of Peter and Paul refuting these scurrilous charges. The workers and soldiers were accused of destroying historical monuments, such as the Winter Palace, the Kremlin, and other places. Foreign correspondents refuted these slanders, but the counter-revolutionary newspapers persisted in their mendacious campaign and tried to incite the most backward sections of the population against the workers and soldiers. The compositors at the printshops of these newspapers refused to set up this vicious stuff.

Notwithstanding the solid support of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, Larin’s resolution was defeated. V. Nogin then got up and read a statement on behalf of a “group of People’s Commissars” in which these supporters of Kamenev’s and Trotsky’s policy of capitulation again demanded the inclusion of Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks in the government and read a statement announcing their resignation from the Council of People’s Commissars. This statement was signed by Nogin and the People’s Commissars A. Rykov, V. Milyutin and I. Teodorovich. It was also backed by Ryazanov, Commissar for Ways and Communications; N. Derbyshev Commissar of the Press; I. Arbuzov, Commissar of State Printing Plants; Yurenev, Commissar of the Red Guard; G. Fedorov, Director of the Disputes Department of the Ministry of Labour; G. Larin, and Shlyapnikov, Commissar of Labour. As soon as Nogin had finished reading his statement a representative of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary group got up and submitted the following interpellation to Lenin as Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars:

“1. Why are not draft decrees and other acts submitted for discussion to the Central Executive Committee?

“2. Does the government intend to abandon its arbitrary and totally unwarranted system of legislating by decree?”[24]

All the declarations of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and of the Kamenev-Zinoviev group pursued the definite object of transforming the All-Russian Central Executive Committee into a bourgeois body, standing in opposition to the Council of People’s Commissars. The attacks launched by the traitors at this meeting—Larin’s speech and resolution, the statement made by the group of People’s Commissars, and lastly, the interpellation of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries—all proved that the defeatists had agreed among themselves to express no confidence in the Council of People’s Commissars and to secure the overthrow of the Soviet Government.

Replying to the interpellation of the Socialist-Revolutionaries, Lenin said:

“The new government could not but take into consideration in the course of its work the obstacles that were likely to arise if all the formalities were strictly adhered to. The situation was far too grave and brooked no delay. There was no time to waste on polishing up the government’s measures, which would only have given them an outward finish without in any way changing their substance.”[25]

On behalf of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary group, Spiro, a member of the Central Executive Committee, moved a resolution expressing no confidence in the Council of People’s Commissars, Uritsky moved another resolution which stated in part:

“The Soviet parliament cannot deny the Council of People’s Commissars the right to pass, without preliminary discussion by the Central Executive Committee, urgent decrees which come within the framework of the general program of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets.”[26]

During the voting on these resolutions Rykov, Nogin, Kamenev, Zinoviev and others left the meeting. This act of treachery was committed with the object of enabling the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries to obtain a majority. But this plan was foiled. Uritsky’s resolution was carried by 25 votes against 23.

Thus, the attempt of the bloc of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and Right defeatists to overthrow the Soviet Government failed.

The situation was extremely critical. The counter-revolutionaries exulted and predicted the downfall of the Soviet Government within the next few days, or even hours.

“The victors are already in a state of utter disintegration!” the Mensheviks howled in their sheet. “One after another the People’s Commissars are resigning even before they have visited the Ministries ‘entrusted’ to them.”[27]

The Menshevik Ministerial Party imagined that the desertion of a few leaders was “the beginning of the end.” A party which was divorced from the masses could not think otherwise.

In his memoirs, Sir George Buchanan, the British Ambassador wrote:

“. . . the secession of so many of their leaders would bring the more moderate members of their party into line with the representatives of the other socialist groups, and that a government would be formed from which Lenin would be excluded.”[28]

The entire bourgeoisie was anticipating, if not the imminent collapse of the proletarian dictatorship, then at least important concessions that would lead to its collapse. The demand that half the seats in the government should be allocated to the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks was practically a demand for the abolition of the proletarian dictatorship.

The Bolsheviks, however, were not in the least dismayed. In reply to these demands the Bolshevik Party stated through the medium of its indomitable leader:

“. . . The only government that can exist after the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets is a Bolshevik Government . . . only a Bolshevik Government can now be regarded as a Soviet Government.”[29]

The treachery of a few deserters failed to shake the unity of the masses which followed the Bolshevik Party “not for one minute, and not one iota,” as Lenin expressed it.[30] The coolness with which Lenin received the blow struck by the traitors was the coolness of the entire Bolshevik Party. At the very time that the Dans and Chernovs were expecting the imminent collapse of the Bolsheviks, Lenin wrote the preface to the second edition of his pamphlet Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power? in the course of which he said:

“The theoretical arguments against a Bolshevik power are feeble to the last degree. These arguments have been shattered.

“The task now is to prove by the practical action of the advanced class—the proletariat—the virility of the workers’ and peasants’ government.”[31]

The entire Bolshevik Party supported the Central Committee in opposition to the blacklegs.

A number of local Party organisations categorically called upon the deserters to return to their posts. Similar demands were made by the workers and soldiers. On November 9, the men of the Finland Regiment sent a delegation to the Smolny to demand that the People’s Commissars who had resigned should immediately return to their posts and share the burden of responsibility with the other Commissars “without yielding an inch of any of the gains, and resolutely to put into operation the decrees which had been promulgated.”

The places of the blacklegs on the Council of People’s Commissars were taken by G. I. Petrovsky, A. G. Schlichter and M. T. Elizarov. The work of the Council was not interrupted for a moment. J. M. Sverdlov was elected to take Kamenev’s place as Chairman of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. The members of the defeatist bloc expressed their regret at Kamenev’s dismissal from the post of chairman, and 14 “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries voted against Sverdlov’s nomination for that post. Kamenev’s departure put a stop to the wavering of a section of the Bolshevik group on the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and shattered the hopes of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries of a split among the Bolsheviks.

On November 6, the Railwaymen’s Executive resolved to transfer its headquarters to Moscow. This was an admission that their manoeuvres had failed. Events immediately before and after this date fully confirmed Lenin’s statement that this Executive was a body without any mass following. Thus, on November 4, the railwaymen on the Nikolayevsky Railway, without consulting their Committee, and contrary to the orders of the Railwaymen’s Executive, had dispatched four troop trains to Moscow to assist the revolutionary forces. One of these carried sailors, while another was an armoured train. The railwaymen of the Kharkov junction passed a vote of no confidence in the Railwayman’s Executive. At a joint meeting of representatives of the Chief Railway Committees held on November 13 and 14, at which the result of the “neutrality” of the Railwaymen’s Executive was summed up, the voice of the masses was heard amidst the mumbling of the bureaucracy. The representative of the Ekaterinburg Railway said: “The Executive’s platform was unanimously supported”; but he immediately added: “the railway workshops passed a vote of censure on the Executive for its activities.”[32] The representative of the Kursk Railway was obliged to confess that “the Bolsheviks’ troops” were transported over the Kursk Railway in spite of the ban of the Railwaymen’s Executive. The railway bureaucrats were swept away by the whirlwind of the revolution.

[1] V. I. Lenin, “Conference of Representatives of the Regiments of the Petrograd Garrison, November 11 (October 29), 1917,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXII, p. 30.

[2] Archives of the Trade Unions, Fund 25, File No. 202, 1917, folio 12.

[3] Ibid., folio 6.

[4] Ibid., folio 9.

[5] Ibid., folio 11.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid., folio 14.

[8] “The Conference of Socialist Parties,” Novaya Zhizn, No. 168, October 31, 1917, p. 3.

[9] V. I. Lenin, “Speech Delivered at a Meeting of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.), November 14 (1), 1917,” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 634.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Minutes of Proceedings of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P., August 1917-February 1918, Moscow-Leningrad 1929, pp. 155-156.

[13] Minutes of Proceedings of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Cossack Deputies. Second Convocation, Published by the All-Russian C.E.C., Moscow, 1918, p. 12.

[14] V. I. Lenin, “The Resolution of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.) on the Agreement with the Socialist Parties, November 15 (2) 1917,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXII, p. 36.

[15] Ibid., 37.

[16] Minutes of Proceedings of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Cossack Deputies. Second Convocation, Published by the All-Russian C.E.C., Moscow, 1918, p. 22.

[17] Archives of the Trade Unions, Fund 25, File No. 202, folio 43.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid., folio 46.

[20] Minutes of Proceedings of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Cossack Deputies. Second Convocation, Published by the All-Russian C.E.C., Moscow, 1918, p. 26.

[21] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

[22] Minutes of Proceedings of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Cossack Deputies. Second Convocation, Published by the All-Russian C.E.C., Moscow, 1918, p. 23.

[23] V. I. Lenin, “The Meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee November 17 (4), 1917,” Speech on “Freedom of the Press,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXII, pp. 43-44.

[24] Minutes of Proceedings of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Cossack Deputies. Second Convocation, Published by the All-Russian C.E.C., Moscow, 1918, p. 28.

[25] V. I. Lenin, “Meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, November 17 (4), 1917. Reply to Interpellation of the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXII, p. 45.

[26] Minutes of Proceedings of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Cossack Deputies. Second Convocation, Published by the All-Russian C.E.C., Moscow, 1918, p. 31.

[27] Leading article Rabochaya Gazeta, No. 205, November 6, 1917.

[28] Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia and Other Diplomatic Memories, Boston, Little, Brown & Company, 1923, Vol. II, pp. 218-19.

[29] V. I. Lenin, “From the Central Committee of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks),” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 650.

[30] Ibid., 651.

[31] V. I. Lenin, “Preface to Second Edition of ‘Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power?’” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 551.

[32] Archives of the Trade Unions, Fund 25, File No. 34, folio 3.

Previous: The Dissolution of General Headquarters

Next: Combating Starvation and Sabotage