Kerensky woke up on the morning of October 29 in excellent spirits. He had not yet learned of the failure of the cadets’ revolt. It seemed to him that fortune was at last beginning to smile on him, and his hopes of victory did not seem as remote as they had been two or three days before.

He visited the armoured train which had been called from the front and told the officers that the German fleet had occupied the Aland Islands and was heading for Petrograd. In the capital, he said, a riotous mob led by German officers had occupied the railway and was preventing the troops from entering Petrograd. He therefore ordered the armoured train:

“To clear the line. . . occupy the Nikolayevsky Railway Station to enable the troops to reach Petrograd. It must act with determination.”[1]

Later in the morning he transferred his headquarters to Tsarskoye Selo, which had been occupied by the Cossacks the previous evening. In the palace at Tsarskoye Selo he resumed his feverish mustering of forces. He sent officers to Luga to accelerate the dispatch of troop trains, and also telegraphed to the commandant of that town ordering him immediately to dispatch a detachment of guerrillas to assist the Cossacks.

General Krasnov’s Cossacks continued the occupation of Tsarskoye Selo. But the reinforcements from the front failed to arrive. Kerensky called for three regiments of the Finland Division from the South-Western Front. The troop trains arrived at Dno, but on hearing about the events in Petrograd the men sent representatives to the city to inform the Military Revolutionary Committee that they would not go into action against the Soviet Government.

Two troop trains arrived in Osipovichi on the Libau-Romni line. The men elected a committee and resolved that under no circumstances would they march against Petrograd.

The garrison in Bologoye, from where Kerensky was expecting assistance, set up a Military Revolutionary Committee which began to organise the dispatch of troops and provisions to revolutionary Petrograd.

Only three Hundreds of the Amur Regiment arrived to assist Krasnov and Kerensky, but even these declared that “they would take no part in the fratricidal war.”[2] They actually refused to perform guard duty in the town and took up their quarters in the adjacent villages. An armoured train mounted with heavy guns, and a Hundred of Orenburg Cossacks, armed only with sabres, also arrived.

The Cossacks began to waver; there was a growing suspicion among them that Kerensky was simply fooling them. More and more often the officers heard what to them was the sinister remark: “We shall march with anybody in the world, but not with Kerensky.”[3]

At first Krasnov was saved, as he himself later admitted, by the Commissars Stankevich and Voitinsky, who succeeded in persuading the Cossacks that it was necessary to advance against Petrograd. The Cossacks calmed down somewhat. In the evening, however, representatives of the Cossack Committee again presented themselves to Krasnov and stated that the Cossacks refused to proceed without infantry. Again Krasnov was obliged to plead with them and, as he subsequently stated in his reminiscences, had to “bring all his influence to bear.”

At last he succeeded once again in convincing the Cossacks that it was necessary for them to march against Petrograd. Nevertheless, it was obvious that a decisive assault was already out of the question.

Meanwhile, the temper of the units of the Tsarskoye Selo garrison became more definite. After their skirmish with the Cossacks at the Orlovsky Gate they returned to barracks and categorically refused to give up their arms.

Realising that the prospect of receiving reinforcements from the front was practically nil, Krasnov made another effort to induce the troops in Tsarskoye Selo to join his forces. With this aim in view, he, on October 29, summoned the officers of all the units of the Tsarskoye Selo garrison. The officers, who were hostile to the Bolsheviks, undertook to persuade their men to join the Cossacks; but they were unable to redeem their promise. At the soldiers’ meetings held to discuss this question the men categorically refused to support the Whiteguard mutiny. All that the officers succeeded in obtaining was a far from definite promise of neutrality.

Upon hearing that the machine-gun company of the 14th Don Regiment was in Tsarskoye Selo, Krasnov summoned its officers and its committee, but here, too, disappointment awaited him. To his astonishment, they all proved to be under Bolshevik influence and categorically refused to render the Cossacks any assistance.

The significance of the events that were unfolding was confirmed by the analysis of the political situation made by Lenin on the same evening at a conference of regimental representatives of the Petrograd garrison.

“I need not dwell at length on the political situation,” he said. “The political question now verges on the military question. It is all too clear that Kerensky has enlisted the Kornilovites; he has nobody else to depend on. . . . At the front nobody supports Kerensky. . . . The masses of the soldiers and peasants will not follow the lead of the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries. I have no doubt that at any meeting of workers and soldiers, nine-tenths will vote for us.

“Kerensky’s attempt is as miserable an adventure as Kornilov’s was.”[4]

The popular character of the Great Proletarian Revolution was displayed in all its magnitude and indomitable strength.

In the evening of October 29 Kerensky learned of the failure of the cadet revolt. This sad news was conveyed to him by those leaders without followers, generals without armies—Stankevich, Gotz, and others—who presented themselves to him in the palace chambers. Gotz had intended to flee to Gatchina together with a group of Socialist-Revolutionaries on the night of October 27, but had been arrested and taken to the Smolny. Later, he was released, and taking advantage of this, slipped away and took part in the revolt. The fugitives from Petrograd were panic-stricken. They wrangled among themselves, blamed each other for the failure, and intrigued against one another. Savinkov for example hastened to General Krasnov, who had put up in the servants’ quarters of Grand Duchess Maria’s palace, and suggested to the General that he should depose Kerensky and place himself at the head of the troops.

“Everybody will be with you and behind you,” he said.[5]

The rest of the night was spent in endless negotiations. Fantastic plans for the movement of entire army corps were drawn up. All hopes now were placed on assistance from the front. They believed that aid would be forthcoming if the Cossacks were moved nearer to the capital. Stankevich, Gotz and Voitinsky displayed the greatest zeal in attempting to persuade the troops to march against Petrograd. They travelled to different sectors of the front in search of units loyal to the Provisional Government. They pleaded with the troops in Tsarskoye Selo and in its immediate environs not to take action against Kerensky and Krasnov, and did all in their power to rouse the “fighting spirit” of the Cossacks. But all the efforts of these political corpses were in vain; nobody heeded them.

Suddenly, a new ray of hope flashed on the horizon. On October 29, at about 10 p.m., when the utter defeat of the cadet revolt had become obvious, a delegation of the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Railwaymen’s Union reached the palace in Tsarskoye Selo.

This Executive Committee had been elected at the Inaugural All-Russian Congress of the Railwaymen’s Union in the latter half of July 1917. Its composition fully exposed the real nature of its alleged “above-party” stand. Of its 41 members, 14 were Socialist-Revolutionaries, six Mensheviks, three Popular Socialists and 11 non-party, most of whom, as Wompe, a leading official of the union admitted, “were actually Constitutional Democrats.” A body of such composition, while claiming to lead the railwaymen, naturally became a centre of “legal” anti-Soviet plotting in the days immediately following the proletarian revolution.

This Executive had its headquarters in Moscow. As soon as the news of the revolution was received, the Executive resolved to take upon itself the role of “saviour of democracy” and of “mediator” between the contending sides. On October 26, the Railwaymen’s Executive transferred its headquarters to Petrograd and on the same day it circulated a telegram in which it expressed doubt about the “validity of the Congress of Soviets now convened” and pointed to the “absence of a government whose authority is recognised all over the country.”[6] The statement clearly revealed the Executive’s attitude towards recent events. It had never denounced the Provisional Government. Regarding the latter as being sufficiently authoritative for the whole country, it was constantly on the doorstep of the Ministry of Railways in the role of conciliator between the railwaymen on strike for the redress of their grievances and the Ministers.

But the leaders of the Railwaymen’s Executive had it brought home to them in the very first days after the October Revolution that they would not succeed in turning the masses of the railwaymen against the Bolsheviks. During the October days a member of the Auditing Committee of the Railwaymen’s Executive made the following entry in his diary:

“Most of our railway clerks and senior officials belong to Right Constitutional Democratic trends; the workshops are almost entirely under Bolshevik influence.”[7]

This situation compelled the Railwaymen’s Executive to launch their campaign to save bourgeois democracy under the flag of “neutrality” in the Civil War. Had the circumstances been different, the Railwaymen’s Executive would have openly advocated the overthrow of the Soviets.

On October 29, when the Krasnov-Kerensky offensive near Gatchina was at its height, the Railwaymen’s Executive adopted a resolution on the question of state power and sent out the following telegram addressed: “To All, To All, To All!”

“The country is without a government. . . . The Council of Peoples’ Commissars established in Petrograd, based, as it is, only on one party, cannot receive the recognition and support of the entire country. A new government must be formed.”[8]

This new government, in the opinion of the Executive, should be formed with the co-operation of all the Socialist parties, from the Bolsheviks to the Popular Socialists, inclusively. The telegram went on to say:

“The Railwaymen’s Union declares that it will endeavour to carry through this decision by all the means in its power, even to the extent of stopping all railway traffic. Traffic will cease at midnight, between October 29 and 30, unless hostilities in Petrograd and Moscow cease by that time.”[9]

On the same day the Railwaymen’s Executive sent its delegation to Kerensky and informed him that railway traffic would cease at midnight if its terms were not accepted. Kerensky and his accomplices jumped at this proposal, which was a trump in their hands with which to play for time. Kerensky summoned the representatives of the parties affiliated to the “Committee for the Salvation” and the Socialist Cabinet Ministers to discuss the proposal and requested the Railwaymen’s Union to provide facilities for them to get to Tsarskoye Selo. The delegates consented and promised to report this to their Executives. Kerensky then demanded that a train be placed at his disposal to go to Moghilev to confer with the army organisations. Having vainly tried to reach General Headquarters and the generals for the past few days, he now tried to do so with the aid of the Railwaymen’s Executive. The delegates granted his request, thus proving that the “neutrality” of the Railwaymen’s Executive was merely a screen for its active assistance to the counter-revolution. After their interview with Kerensky the delegates returned to Petrograd.

In Petrograd, in the meantime, intense preparations to repel Krasnov’s forces were continued. After liquidating the cadet revolt, the Military Revolutionary Committee took energetic measures to defend the Red capital and to inflict a crushing blow upon the enemy.

A plan of operations was there and then drawn up. The Pulkovo Heights, which were to serve as the centre of the line, were occupied by the Red Guard, of which the Vyborg District detachments formed the main core. The right flank, in the vicinity of the village of Noviye Suzy was occupied by sailors from Helsingfors and Kronstadt. The left flank, in the district of Bolshoye and Podgornoye Pulkovo, was occupied by the Ismailovsky and Petrograd Regiments. Here four armoured cars were posted. The total strength of the revolutionary forces was about 10,000. There was a severe shortage of artillery; the Soviet troops had only two field guns. This was felt very acutely next day, when the fighting commenced, for General Krasnov had a far larger number of guns at his disposal.

The Soviet units spent the night digging in. The Staff took up its quarters in a cottage on the outskirts of Podgornoye Pulkovo and issued its final orders, distributed the provisions and sent the various units of armed workers who continued to arrive to their appointed positions. The offensive of the Soviet troops was fixed for the morning of October 30.

To accelerate the offensive against Krasnov’s troops Stalin commissioned Sergo Orjonikidze to go to the front at the head of a group of Bolsheviks. On October 29, the Military Revolutionary Committee ordered the Commissar of the Baltic Railway Station to place a special locomotive at Orjonikidze’s disposal and on this Orjonikidze travelled to the front. On his arrival he inspected the positions and talked with the Red Guards. His calm confidence that victory would be achieved greatly cheered the men. He carefully studied the plan for the offensive and sent a report of it to Lenin and Stalin. Stalin considered it necessary to have trenches dug and barricades erected in Pulkovo itself, in case the Cossacks succeeded in breaking through.

Representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee, including D. Z. Manuilsky, visited the lines at Pulkovo and reported that:

“The spirit of the men is splendid: firm, determined and staunch. In the workers’ guard a shortage of officers is felt. The soldiers are resolute. The sailors too. . . . The men were informed that the cadets have been crushed and this had a profound effect.”[10]

At night the representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee visited the Staff Headquarters. In a room, humming with conversation and filled with tobacco smoke, they found many officers and soldiers. Maps were spread out on the table. The plan of the offensive was being discussed. It was decided to strengthen the flanking movement on the Krasnoye Selo side. The soldiers, particularly the scouts, suggested alterations to the plan as it was being discussed. The Red Guards, many of whom had taken part in the capture of the Winter Palace, demanded that the offensive should be accelerated. Their fighting spirit was very high and they were eager to push forward. Their ardour infected the soldiers and the sailors.

The representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee learned that there was an acute shortage of artillery and reported this to the Committee.

On receiving the report of their representatives the Military Revolutionary Committee decided to send two comrades to strengthen the Staff at the front, and also to send additional artillery and motor vehicles. A group of comrades was dispatched to procure the automobiles and after a few hours of energetic effort they requisitioned several score, which were hurriedly dispatched to Pulkovo. At the same time 50 horses were requisitioned to haul the guns.

Meanwhile Lenin and Stalin had been unremitting in their efforts to reinforce the front. On the morning of October 30 they summoned all the district organisers of the Bolshevik Party. About ten or twelve men gathered and Lenin informed them about the situation at Pulkovo. Lenin and Stalin urged the necessity of rousing the masses, as it might be necessary to fight in the city. They recommended that arms be procured and detachments formed. Lenin, personally wrote on a half-sheet of notepaper a mandate authorising the bearer to take from the Putilov Works all that was needed for the front.

Early in the morning of October 30 a student, who had managed to make his way from Petrograd, presented himself to Krasnov and delivered a message from the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces. The panic-stricken leaders of the cadet revolt wrote that “the situation in Petrograd is awful. . . .” The Red Guards are “smashing the cadets.” “The infantry regiments are wavering and are standing idle. . . .” “The Cossacks are waiting” until the infantry units move. All their hopes now rested on Krasnov’s Corps. “The Council of the Union demands your immediate advance on Petrograd.”[11]

General Krasnov ordered the Cossacks to advance. He sent one Cossack Hundred to Krasnoye Selo against the right flank of the Red forces. A half-Hundred was sent to probe the left flank of the Red forces in the vicinity of Bolshoye Kuzmino. A squadron was sent to reconnoitre in the direction of Slovyanka and Kolpino. The artillery, covered by Cossacks, was deployed in the vicinity of the village of Redkoye Kuzmino. Here, somewhat to the rear, Krasnov’s main forces were concentrated. Krasnov personally watched the course of the battle from an observation post on the outskirts of Redkoye Kuzmino.

The Red forces did not wait for the Whiteguards to attack. On the morning of October 30, in accordance with the operational plan, the Red Guards launched their attack. Headed by their commanders, they charged down the hillside.

The Cossacks had a superiority in artillery which, handled by experienced gunners commanded by officers, inflicted heavy losses on the Red troops. Many of the workers were under artillery fire for the first time in their lives. In the midst of the fighting the commanders taught these young soldiers how to take cover. The Red Guards hugged the ground and the shrapnel burst over their heads. The enemy artillery put up a barrage behind which the Cossacks prepared to advance.

But the Red Guards did not flinch. Cheers were heard, rising in volume and again the Red Guards rose and charged.

The Cossacks, seasoned soldiers and tempered in battle though they were, failed to withstand the impetuous onslaught of the Red Guards. The long dense lines of men in civilian overcoats poured down the slopes of the Pulkovo Heights. It seemed as though masses in incalculable numbers, the entire nation, was rushing to overwhelm the handful of mutineers. The Cossacks hesitated and began to waver, and this increased as the Red Guards advanced.

On the right flank where the Kolpino detachment was operating, a Cossack charge broke against the staunchness of the Red Guards. The latter had two armoured cars, but the shells from Krasnov’s artillery pitted the road with deep craters. One of the armoured cars came to a standstill and the Cossacks, under the impression that it had been crippled by shell fire, drew their sabres and charged. The Red Guards allowed them to come close up and then opened a withering rifle and machine-gun fire. The Cossacks were mown down. Their commander and most of the men were killed. The casualties of the Kolpino Detachment amounted to one wounded and one missing.[12]

Towards noon three batteries of artillery arrived from Petrograd. The offensive of the Red forces was now supported by gunfire of increasing intensity. The shells dropped not only in the Cossacks’ forward positions, but also in their rear lines. Their guns were gradually silenced and they began to fall back, pursued by the Red Guards. Outflanking the Cossacks, the Red units captured Bolshoye Kuzmino. The Petrograd and Ismailovsky Reserve Regiments, advancing in open order, came out on the railway line and approached Tsarskoye Selo.

Kerensky was in the palace at Gatchina. All the swagger and arrogance which he had displayed the day before had now vanished. Again he rushed hither and thither from telegraph instrument to telephone. He no longer trusted the people around him. General Krasnov had appointed a chief of the guard of Gatchina and had requested Kerensky to sanction the appointment. Kerensky did so, but fifteen minutes later he appointed his own “super-chief.”[13]

The bad tidings he received from Petrograd drove him to despair. Just as he had done during the siege of the Winter Palace, he again decided to flee or, as he put it, “to leave immediately to meet the approaching troop trains.” Early in the morning of October 30 he sent Krasnov a note informing him of his impending departure. He also drew up a document resigning his powers as Prime Minister in favour of N. D. Avksentyev, one copy of which he handed to Gotz and another to Stankevich. But later in the day, when all the preparations for the flight had been completed, Savinkov, accompanied by representatives of the Council of Cossack Forces, approached him on behalf of Krasnov and stated that his departure would demoralise the troops, and that he ought to wait until the battle was over.

Kerensky remained, but continued to send out telegrams calling for the dispatch of troops from the front. At 4:30 p.m. he sent the following telegram to General Dukhonin:

“Please order the dispatch of shock units and cavalry if any difficulties arise in dispatching infantry. Exert all efforts to accelerate the movement of the troops.”[14]

At the time he dispatched this telegram Kerensky was already aware that the infantry units which General Headquarters had been promising all this time had refused to come to his aid. The original draft of the above telegram, which was preserved in Kerensky’s notebook, contained the following lines which he had crossed out for fear that they might become public:

“Information has been received of incipient unrest among the infantry of the 17th Army Corps which had been dispatched to Petrograd.”[15]

At the beginning of October, General Headquarters had ordered the transfer of the 17th Army Corps from the Rumanian to the Northern Front and placed in the Supreme Commander-in-Chief’s reserves in the region of Vitebsk-Polotsk-Orsha. Probably this Army Corps was already being got ready to be used against the Bolsheviks, for General Headquarters more than once emphasised that:

“In view of the gravity of the situation, reliable troops are needed on the Northern Front, troops that are more concerned about the defence of the country than with politics.”[16]

For two weeks troop trains carrying units of this Army Corps had been arriving at their destination when suddenly an order was received to move the regiments with artillery to Tsarskoye Selo. The Army Corps Commander hastened to entrain brigades of infantry and three batteries of artillery. Telegram after telegram was received from General Headquarters. An order arrived to occupy the railway station at Dno. In reply to the perplexed commander’s question as to what he should do: occupy Dno or go to the capital?—General Headquarters stated: entrain for Petrograd.[17] The units arrived at the railway station, but they found no railway cars. Reports came in from regimental commanders to the effect that the railwaymen were not allowing the soldiers to entrain, or else were providing trains without locomotives. Then more alarming news was received—the Bolsheviks had captured the railway stations and towns on the line of route. The Corps Commander telegraphed to a Divisional Commander as follows:

“The Bolsheviks have captured the Telegraph Office in Vitebsk. I order you to place one of the regimental commanders in command of the guard at Gorodok Station to prevent it from being captured by the Bolsheviks. Act resolutely.”[18]

But a message arrived from Gorodok stating that Bolshevik meetings were being held there. The soldiers refused to entrain. They had seized the railway engines and were demanding to be sent back to their former stations.

The commanders failed to induce a single regiment to go to the aid of Krasnov and Kerensky. Nor did the armoured cars upon which Krasnov had placed such hopes turn up. The Armoured Car Unit commanded by Captain Artifexov refused to entrain at Rezhitsa. The Captain ordered the unit to proceed by road, but on the way the soldiers mutinied and the Captain himself was obliged to seek safety in flight.[19]

The 5th Armoured Car Detachment, which Kerensky had personally called up, also failed to appear. When the second unit of this detachment was ordered in Kerensky’s name to proceed to Petrograd it decided to send a delegate to the capital to enquire why it was being called there. Nevertheless, the Commander succeeded in inducing four armoured cars and 14 motor trucks and passenger cars to go to Kerensky’s aid by road. But even this detachment did not get beyond Staraya Russa; the soldiers refused to go any further.[20]

At 5 p.m., on October 30, Kerensky called for the 17th Cavalry Division which, according to his information, was “definitely opposed to the Bolsheviks.” In the same telegram he called for the dispatch of troops from Moscow “if the news that complete calm now prevailed in Moscow is correct.”[21] This news proved to be incorrect, however. At that time, the counter-revolutionaries in Moscow were themselves appealing to General Headquarters for assistance.

At 5:45 p.m. Kerensky ordered the chief of the Gatchina Aviation School to mount machine guns on two aeroplanes and immediately place them at the disposal of General Krasnov. But at that moment the latter sent bad news from Pulkovo: the Bolsheviks had defeated the Cossacks and Krasnov’s troops might retreat to Gatchina at any moment. It was necessary to take measures to defend the town. At 7:45 p.m. Kerensky ordered the chief of the Aviation School to transfer all his available machine guns to Gatchina to protect the town.

Not one of the numerous units which had been summoned from the front even reported its whereabouts.

Kerensky’s panic may be judged from the following telegram which he sent to the commander of the Polish Rifle Division at 8 o’clock that night:

“I order you urgently to entrain your division and proceed with it to Gatchina.”[22]

For this at least ten trains were required, and to load ten trains with troops and equipment must take time. Kerensky, however, needed assistance at once; the Cossacks at Pulkovo were obviously fighting a losing battle.

The offensive launched by the Red units influenced the garrison at Tsarskoye Selo, but certainly not in Krasnov’s favour. Meetings were again held in the barracks and the resolutions adopted at all of them were couched in identical terms. The soldiers called upon Krasnov to cease hostilities, threatening to attack the Cossacks in the rear if he failed to do so.

Krasnov learned of the temper prevailing among the garrison of Tsarskoye Selo from the bourgeois youth of that town who were employed as spies.

In the end, the Krasnoye Selo garrison supported the offensive of the Red Guard. On October 29, Cossack patrols came into collision with units of the 171st and 176th Reserve Regiments, which were quartered in Krasnoye Selo. Here the Pavlovsky and Chasseur Reserve Regiments, and detachments of sailors arrived by order of the Military Revolutionary Committee. After a heavy exchange of fire, the Cossacks retreated. The Krasnoye Selo garrison, covered on the Gatchina side by the Pavlovsky Regiment, launched an attack in the Tsarskoye Selo direction and reached the Gatchina-Tsarskoye Highway. The machine-gunners of the 2nd Regiment, and the artillery sent from Petrograd, joined the attacking units.

On the night of October 29, the Krasnoye Selo detachment captured a trainload of artillery and 400 men. As the soldiers could not unload the guns from the train they removed the locks, in spite of the fire from a Whiteguard armoured train which had come up. The prisoners were sent to Krasnoye Selo.

Next day, while the Red Guards launched their offensive at Pulkovo, the Krasnoye Selo detachment resumed its operations against the Cossacks’ flank and rear. True, they did not make much headway but their mere presence in the Vitgolovo-Maliye Kobozi area and active operations in the direction of Tsarskoye Selo constituted a threat to Krasnov’s main forces.

At 7 p.m. that day the Commissar of the 176th Infantry Reserve Regiment sent the following dispatch to the Military Revolutionary Committee:

“All rumours about the defeat of the Krasnoye Selo detachment are false. We are conducting a vigorous offensive against Tsarskoye Selo and Alexandrovka. The sailors are fighting like heroes and the soldiers are not a whit behind them. The 176th and 171st Infantry Reserve Regiments are living up to their revolutionary reputation.”[23]

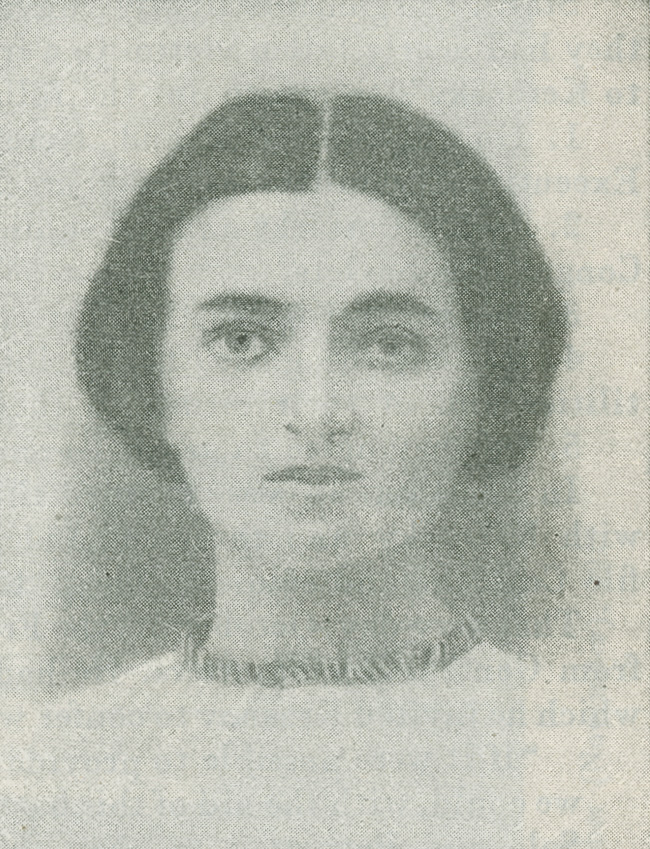

Continuing their offensive, the Red troops occupied Tsarskoye Selo. The Cossacks retreated towards Gatchina. No precise data as to the casualties on the Pulkovo Front have been preserved, only approximate figures are available. The bulletin of the Military Revolutionary Committee estimated the number of killed at 200. Among these was Vera Slutskaya, an active member of the Petrograd organisation of the Bolshevik Party who went to the front in the capacity of a political worker.

On the evening of October 30, Krasnov and his Staff arrived in Gatchina. All night long conferences were held in the palace at which the officers discussed their plan of further operations. Representatives of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party kept on arriving to see Kerensky. One of these was Victor Chernov. On learning of the arrival of their leader, a delegation of Socialist-Revolutionaries from Luga came to seek advice and to enquire whether their line of policy was correct. On the previous evening they had decided to maintain neutrality and to allow troop trains of both sides to pass, i.e., those going to the assistance of the Kerensky government and those called out by the Bolsheviks. Chernov approved of this resolution, but Stankevich said that it was a stab in the back of the government. To this Chernov replied:

“From the practical point of view, one thing is important, and that is to allow the government’s troop trains to pass; for evidently no troop trains are going to the Bolsheviks.”[24]

Kerensky received disastrous news from General Headquarters: The Fifth Army had decided to send assistance to the Bolsheviks; armed collisions had broken out in the Twelfth Army. The retreat to Gatchina completely demoralised the Cossacks. They even refused to guard the bridges at the river Izhora. “It’s no use,” they said, according to Krasnov’s own testimony, “we Cossacks cannot stand alone against the whole of Russia. If all Russia is with them, what can we do?”[25]

On October 31 a council of war was held at which it was decided to enter into negotiations with the Bolsheviks in order to gain time until reinforcements arrived. Two proposals were submitted, one in the name of Krasnov addressed to the commander of the Red Forces on the Gatchina Front, and the other under Kerensky’s signature addressed to Petrograd. Both proposals were couched in obviously unacceptable terms. Kerensky demanded that the Bolsheviks should cease hostilities and submit to a new democratic government. This government was to be formed by agreement with the “existing” Provisional Government and representatives of all political parties and of the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution.” That this offer of “peace” negotiations was a ruse on the part of Kerensky and Co. with the object of gaining time was confirmed by Krasnov himself. As he subsequently confessed:

“Stankevich was to go to Petrograd to seek an agreement or assistance; Savinkov went to fetch the Poles, and Voitinsky went to General Headquarters to ask for shock battalions.”[26]

Stankevich carried Kerensky’s proposals to Petrograd. Taking advantage of the fact that the best units and the most progressive soldiers had been sent to the front at Pulkovo, the “Committee for the Salvation” sent its agents to all the regiments of the garrison with the object of influencing the more politically backward soldiers who had remained in the capital. These agents told the soldiers that Kerensky stood for peace, whereas the Bolsheviks were fomenting civil war. The officers tried to persuade the soldiers to call upon the Bolsheviks to put a stop to the bloodshed. The counter-revolutionaries endeavoured to make political capital out of the soldiers’ passionate desire for peace.

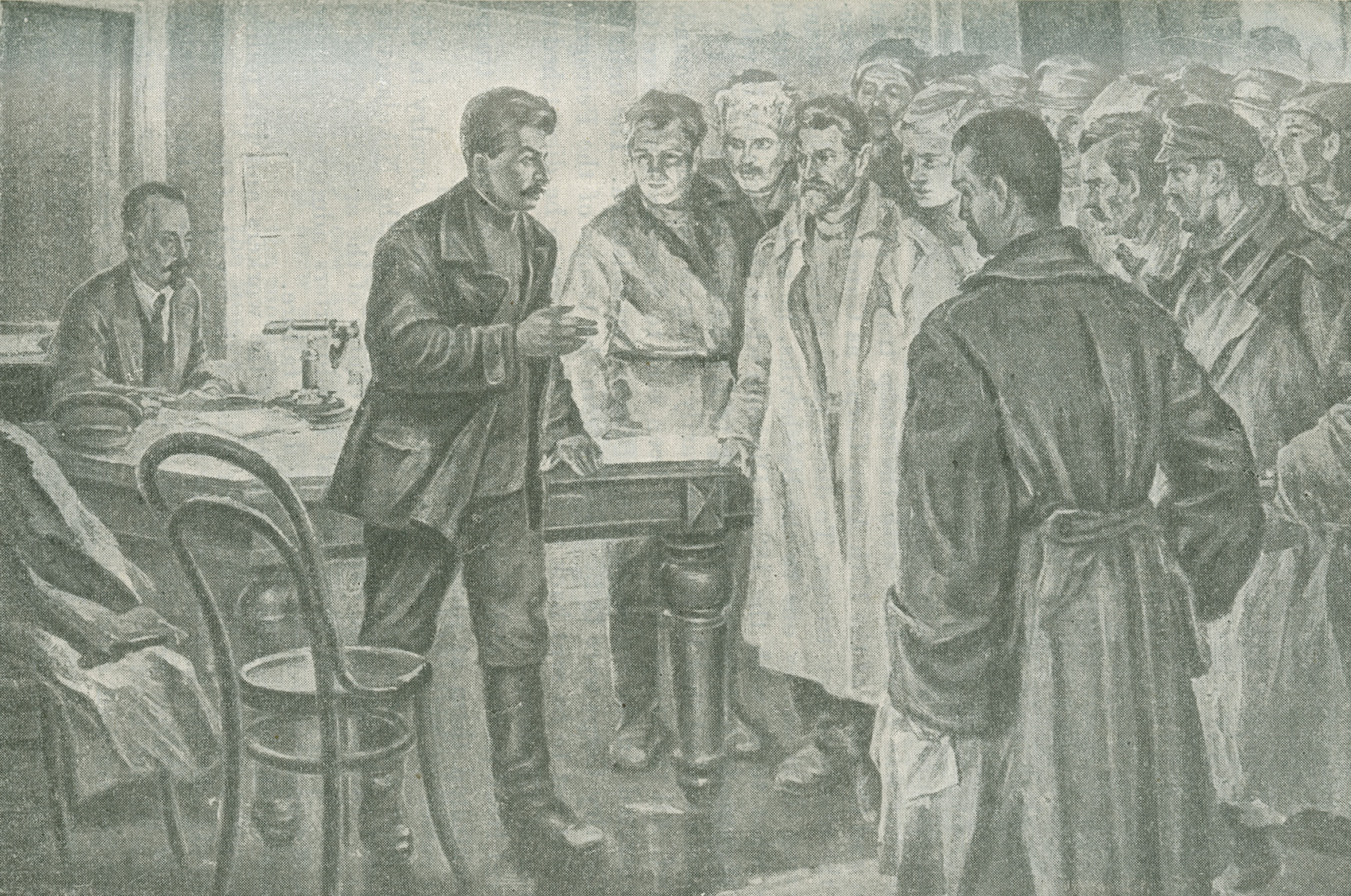

Some of the regiments elected delegates and sent them to the Smolny. During the course of the day delegates arrived from the Chevaliers of St. George, the 3rd Rifle Division and other units. In the evening of October 31, delegates arrived representing the Lithuanian, Semyonovsky, Petrograd, Kexholm, the Grenadier, Ismailovsky, Moscow and the Preobrazhensky Regiments. Among them were soldiers from the front. The chairman of the deputation, a private of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, read an instruction which the delegates had received—obviously dictated by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks—to the effect that the Military Revolutionary Committee and the garrison of Petrograd should appoint representatives consisting of members of all Socialist parties, including the Popular Socialists, for the purpose of negotiating with Kerensky.

The deputation was received by Stalin. He described to the men the situation at the front and explained that the proposal they had made meant assisting Kerensky, whose only object was to gain time. Finally, Stalin urged that it was impossible to negotiate with Kerensky.[27]

Stalin’s words convinced many of the delegates. The representatives of the Lithuanian Regiment stated that they had never had any disagreement with the Military Revolutionary Committee, but they had no information about the character of the negotiations.

Stalin spoke again and explained Kerensky’s manoeuvre.

“Kerensky has submitted an ultimatum demanding the surrender of arms,” he added.[28]

Stalin’s arguments finally convinced the delegates, who realised that they had nearly fallen victim to a fraud. They decided to send a deputation to Kerensky’s troops to put the following five questions to them:

1. Do the Cossacks and Kerensky’s soldiers recognise the Central Executive Committee as the source of power responsible to the Congress?

2. Do the Cossacks and the soldiers recognise the decisions of the Second Congress of Soviets?

3. Do they recognise the decrees on peace and land?

4. Do they recognise the possibility of an immediate cessation of hostilities and of their return to their former stations?

5. Do they agree to arrest Kerensky, Krasnov and Savinkov?[29]

In addition, it was decided that the deputation should not negotiate with Kerensky and the commanders, but exclusively with the rank-and-file Cossacks and soldiers. Thus, Kerensky’s last manoeuvre failed.

That very day, October 31, the French General Niessel arrived in Gatchina from General Headquarters. He had a long interview with Kerensky, after which he invited Krasnov to confer with him. At this conference Krasnov said:

“If it were possible to provide at least one battalion of foreign troops, we could, with the aid of this battalion, compel the garrisons of Tsarskoye Selo and Petrograd to obey the government.”[30]

The counter-revolutionaries could see no way out of their predicament except foreign intervention.

At 6 p.m. on October 31 Kerensky set all the wires buzzing with a telegram to the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Railwaymen’s Union stating that the proposal for an armistice had been accepted and that his representative had left for Petrograd.

At 8:45 p.m. that same evening he sent the following telegram to the “Committee for the Salvation” and to the Railwaymen’s Executive:

“Conforming to the proposal of the ‘Committee for the Salvation’ and of all the democratic organisations affiliated to it, I have ceased operations against the insurgent troops and have commissioned Stankevich, Representative-Commissar of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, to open negotiations. Take measures to prevent useless bloodshed.”[31]

Kerensky tried to avoid negotiating with the victorious Bolsheviks, but while the endless conferences and mutual recrimination dragged on, representatives of the Red Guard, the Petrograd regiments and the sailors appeared in Gatchina and began to negotiate with the rank and file. The workers began to reach an understanding with the Cossacks. They urged them to stop fighting and to arrest Kerensky, promising that after that they would be allowed to return to their homes on the Don. The Cossacks readily agreed to this and went off to place a guard over Kerensky’s quarters. The latter, however, had been warned.

At 10:15 a.m. on November 1 Kerensky sent another very urgent telegram to the Railwaymen’s Executive stating that he had accepted the proposal for an armistice and was waiting for a reply.[32] But the Red Guards and sailors were already on the first floor of the palace. At 1 p.m. Kerensky wired to General Dukhonin:

“In view of my departure for Petrograd, I order you to assume the duties of Supreme Commander-in-Chief.”[33]

This was the last telegram, boastful and false as ever, that this Prime Minister and Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Provisional Government dispatched. Instead of going to Petrograd, as he had stated in the telegram, he, at about 3 p.m. on November 1, escaped from the ancient palace by a secret corridor, abandoning the demoralised counter-revolutionary forces near Petrograd to their fate. The revolutionary troops occupied Gatchina and arrested the Staff of the 3rd Cavalry Corps together with General Krasnov.

Late that night, Baranovsky, Quartermaster-General of the Northern Front, called up General Dukhonin at General Headquarters and informed him of the failure of Krasnov’s operations and of Kerensky’s flight. He enquired what was to be done with the troop trains of the 3rd Finland Division and the units of the 17th Army Corps, as Gatchina had been occupied by the revolutionary troops. To direct these trains to Gatchina meant surrendering them one by one to the Bolsheviks, he said. He also wanted to know what to do with the 182nd Division which the Socialist-Revolutionary Mazurenko had intended to bring to Kerensky’s aid.

Dukhonin replied that he was temporarily acting as Supreme Commander-in-Chief. All the troops which had been sent to Krasnov’s aid were to be concentrated in the region of Luga-Plusna-Peredolskaya. The units of the 3rd Cavalry Corps were to be isolated from the troops of the Petrograd garrison, but not to be sent back to Ostrov. They were to be dispatched to the region of Chudovo.

General Headquarters still hoped to be able to make use of these troops and concentrated them at places not far from Petrograd.

“It is easier to bring up supplies, and the presence of cavalry in this area will have a more salutary effect in the region of the Nikolayevsky Railway,”[34] said Dukhonin, explaining his choice of the area in which to quarter these troops. But even General Headquarters admitted that the Kerensky-Krasnov expedition had ended in failure.

Backed by the overwhelming majority of the workers and the toiling peasants, the young Soviet Government crushed the revolt of the remnants of the old regime. The first anti-Soviet mutiny was crushed. The dictatorship of the proletariat achieved its first important victory.

[1] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 49, 1917, folio 20.

[2] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 162.

[3] Ibid., p. 163.

[4] V. I. Lenin, “Conference of Representatives of the Regiments of the Petrograd Garrison, November 11 (October 29), 1917,” Collected Works, Vol. XXII, pp. 30-31.

[5] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 163.

[6] “The Congress of Soviets.” “The Railwaymen Refuse to Recognise the Rule of the Bolsheviks,” Rabochaya Gazeta, No. 198, October 28, 1917.

[7] P. Wompe, The October Revolution and the Railwaymen, Published by the Central Committee of the Railwaymen’s Union, Moscow, 1924, p. 22.

[8] Minutes of the Proceedings of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P., August 1917-February 1918, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1929, p. 145.

[9] Ibid., p. 146.

[10] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 2, File No. 14, Part II, folio 48.

[11] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 165.

[12] “The Bulletin of the Military Revolutionary Committee,” Novaya Zhizn, No. 170, November 2, 1917.

[13] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 543, File No. 10, 1917, folio 26, reverse side.

[14] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, 1917, folio 25.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Central Archives of the Military History, Fund of the Office of the Minister for War, File No. 1592fs, folio 53.

[17] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Seventeenth Army Corps, File No. 424-095, folios 423, 424.

[18] Ibid., folio 367.

[19] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 165.

[20] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 102, 1917, folios 4, 5.

[21] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, 1917, folios 27, 28.

[22] Ibid., folio 33.

[23] “The Krasnoye Selo Detachment,” Pravda, No. 175, November 1, 1917.

[24] V. B. Stankevich, Memoirs, 1914-1919, Berlin, 1920, p. 279.

[25] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 171.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 2, File No. 14, Part I, folio 14.

[28] Ibid.

[29] “The Meeting of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Novaya Zhizn, No. 169, November 1, 1917.

[30] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 172.

[31] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, 1917, folio 35.

[32] Ibid., folio 36.

[33] Ibid., folio 39.

[34] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, Quartermaster-General’s Administration, File No. 816, folio 152.

Previous: Proletarian Petrograd in the Fight Against the Whiteguards

Next: The Beginning of the Insurrection