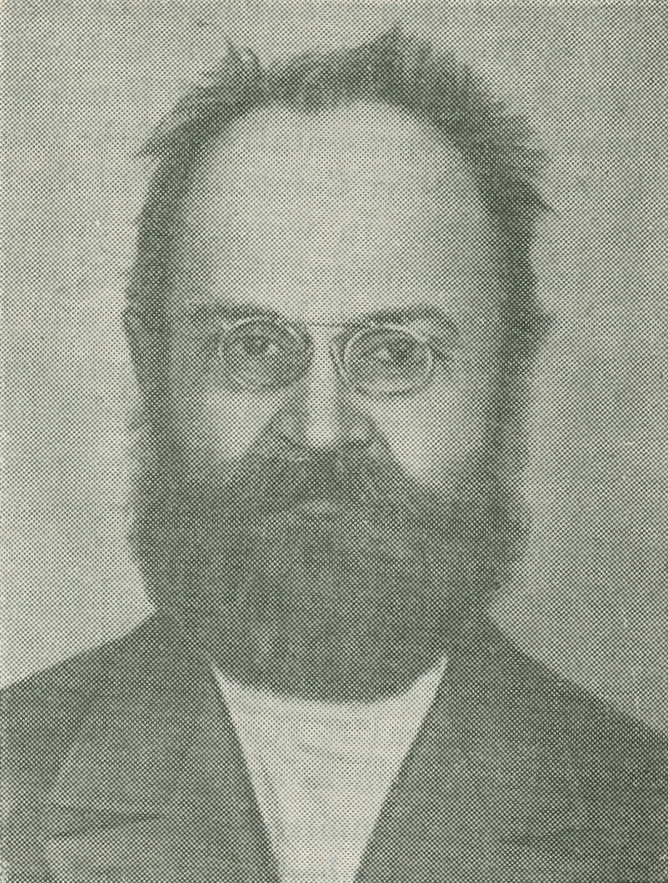

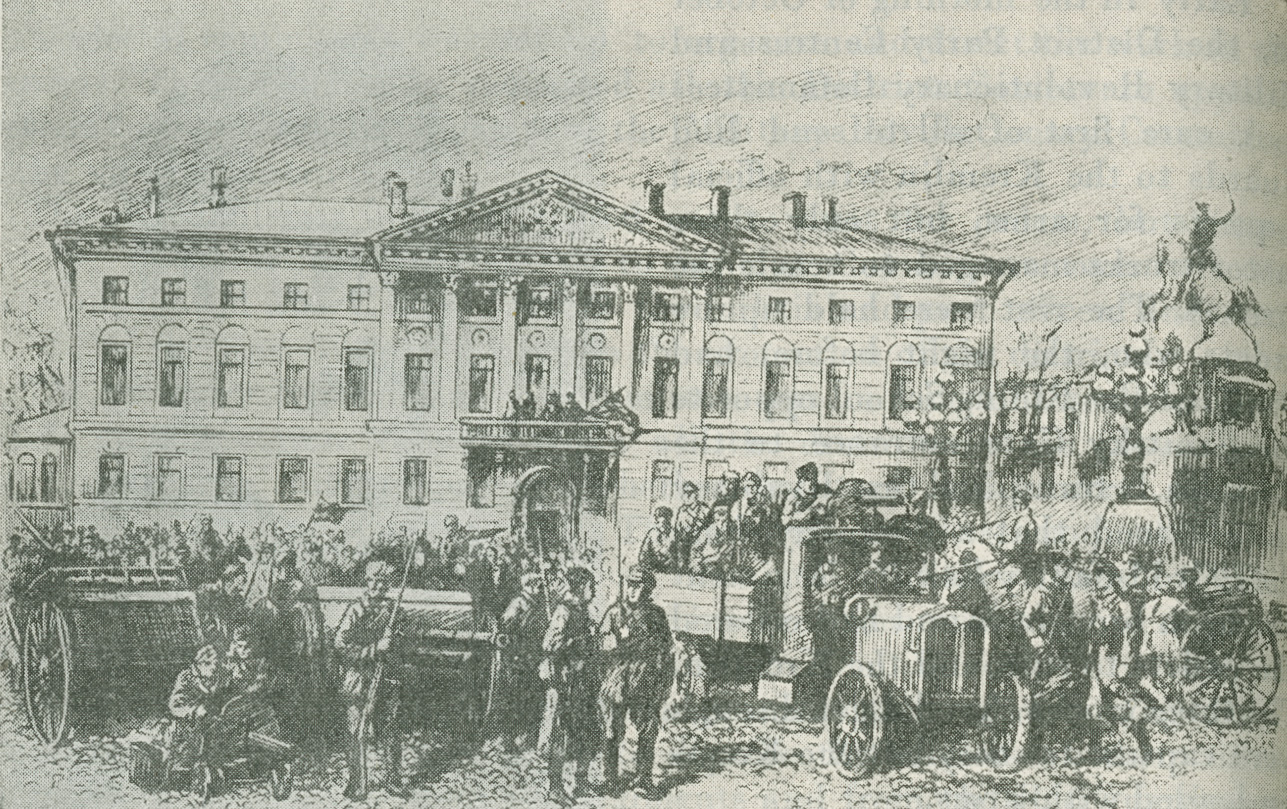

n October 24, telephone communication between Moscow and Petrograd was cut off the whole day and nobody knew what was going on in the capital. It was not until the morning of October 25 that Nogin, the Chairman of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, who was then in Petrograd, telephoned the Moscow Soviet. There, a joint meeting of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies and the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies had been fixed for 10 a.m. but the deputies had not yet arrived. Only the Bolsheviks had arrived for a meeting of their group. When Nogin’s telephone message was received, A.S. Vedernikov, the chief of the Red Guard of the Soviet, happened to be in the room and he communicated the message to the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party, which then had its headquarters in the Hotel Dresden, in Skobelev Square opposite the Moscow Soviet.

n October 24, telephone communication between Moscow and Petrograd was cut off the whole day and nobody knew what was going on in the capital. It was not until the morning of October 25 that Nogin, the Chairman of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, who was then in Petrograd, telephoned the Moscow Soviet. There, a joint meeting of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies and the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies had been fixed for 10 a.m. but the deputies had not yet arrived. Only the Bolsheviks had arrived for a meeting of their group. When Nogin’s telephone message was received, A.S. Vedernikov, the chief of the Red Guard of the Soviet, happened to be in the room and he communicated the message to the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party, which then had its headquarters in the Hotel Dresden, in Skobelev Square opposite the Moscow Soviet.

The Moscow Committee was not yet aware of what had taken place in Petrograd. At the time Nogin’s telephone message arrived the Committee was in session, discussing the question of forming a fighting centre under the auspices of the Moscow Soviet. The question had arisen in connection with the suppression of the Soviet in Kaluga. Everybody recognised that urgent measures were necessary, but nobody as yet talked about an immediate insurrection. It was decided:

“Forthwith to instruct the [Bolshevik] group in the Soviet immediately to form a fighting centre on the basis of proportional representation, the body to consist of three Bolsheviks, one Menshevik, one Socialist-Revolutionary, one representative of the Red Guard, and one representative of the Staff of the Military Area. Proportionate strength: four Bolsheviks, three others.

“The work of the military organisation is to continue. The military bureau is instructed to launch a political campaign in all the units with the view to inducing them to declare that they will obey no orders without the sanction of the Soviet.”[1]

The candidates for this Soviet fighting centre were nominated there and then.

The Moscow Committee then discussed the question of forming a Party fighting centre. It was unanimously decided without discussion forthwith to form a single Party fighting centre consisting of two comrades from the Regional Bureau, two from the Moscow Committee and one from the Area Committee of the Bolshevik Party. In addition, it was proposed to include one representative of the trade unions and one of the military organisation. This Party Centre was invested with full powers.

The election of the members of this centre was barely concluded when news was received of the insurrection in Petrograd. The Soviet fighting centre had not yet been formed; the joint meeting of the Soviets had been deferred until 3 p.m., but the situation called for immediate action. The Party Centre, remaining in the Hotel Dresden, therefore issued an order to seize the General Post Office and the Central Telegraph Office, to post a guard in the Polytechnical Museum, in the Lecture Hall of which the meeting of the Soviets was to be held, and to suppress the bourgeois newspapers. All the District Committees of the Bolshevik Party were instructed to set up district fighting centres and to occupy the militia stations. The Regional Bureau of the Bolshevik Party was instructed to send a messenger to Alexandrov with a request for hand grenades. It sent instructions to Orel and Bryansk to form defence bases in case the counter-revolutionaries launched an attack in Moscow. The Regional Bureau, in its turn, sent an organiser of the Smolensk Citizen’s League* to the city of Smolensk, and also informed Tula of what was going on in Moscow.

The task of seizing the General Post Office and Central Telegraph Office was entrusted to A.S. Vedernikov, who decided to call out units of the 56th Regiment for this purpose. The regimental staff and two battalions of this regiment were quartered in the Pokrovsky Barracks. The 1st Battalion and the 8th Company were quartered in the Kremlin, and companies of the 2nd Battalion were quartered in the Zamoskvorechye District.

Accompanied by O.M. Berzin, a Sub-Lieutenant of the 8th Company, Vedernikov hurried to the Pokrovsky Barracks where he found a meeting of the Regimental Committee in progress. The proceedings were interrupted and Vedernikov informed the Committee of the overthrow of the Provisional Government in Petrograd and requested that two companies of the regiment be detailed for the purpose of capturing the Post and Telegraph Offices. The Chairman of the Committee, a Socialist-Revolutionary, after a considerable amount of wriggling, submitted the question for discussion. The officers on the Committee demanded that everybody should keep calm and await orders from Military Area Headquarters. Some of the privates—Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks—demanded that the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies should be warned. It was evident that the Regimental Committee was deliberately procrastinating. Suddenly a Bolshevik private jumped up and shouted:

“Boys, don’t let these fellows lead us by the nose!... We must act. There’s been quite enough talk. Come on, let’s line up the companies!”

The soldiers jumped from their seats. Somebody shouted:

“You line up your 11th Company and I will call out mine!”

The members of the soldiers’ section of the Regimental Committee rushed to their respective companies to call out their men. About fifteen minutes later two companies—the 11th and the 13th—were lined up in the barrack square. They quickly numbered and marched through the gates. Here they encountered the Regimental Commander, but the men ignored him.

The company arrived at the Central Telegraph Office and General Post Office, occupied all the entrances and posted a guard, but did not interrupt the work of the employees. They committed a blunder, however, which led to serious consequences later. Next door to the General Post Office and Central Telegraph Office was the Inter-City Telephone Exchange. The soldiers occupied this building and with that considered their task finished. They should, however, have occupied the Central City Telephone Exchange in Milyutinsky Street too. This they failed to do.

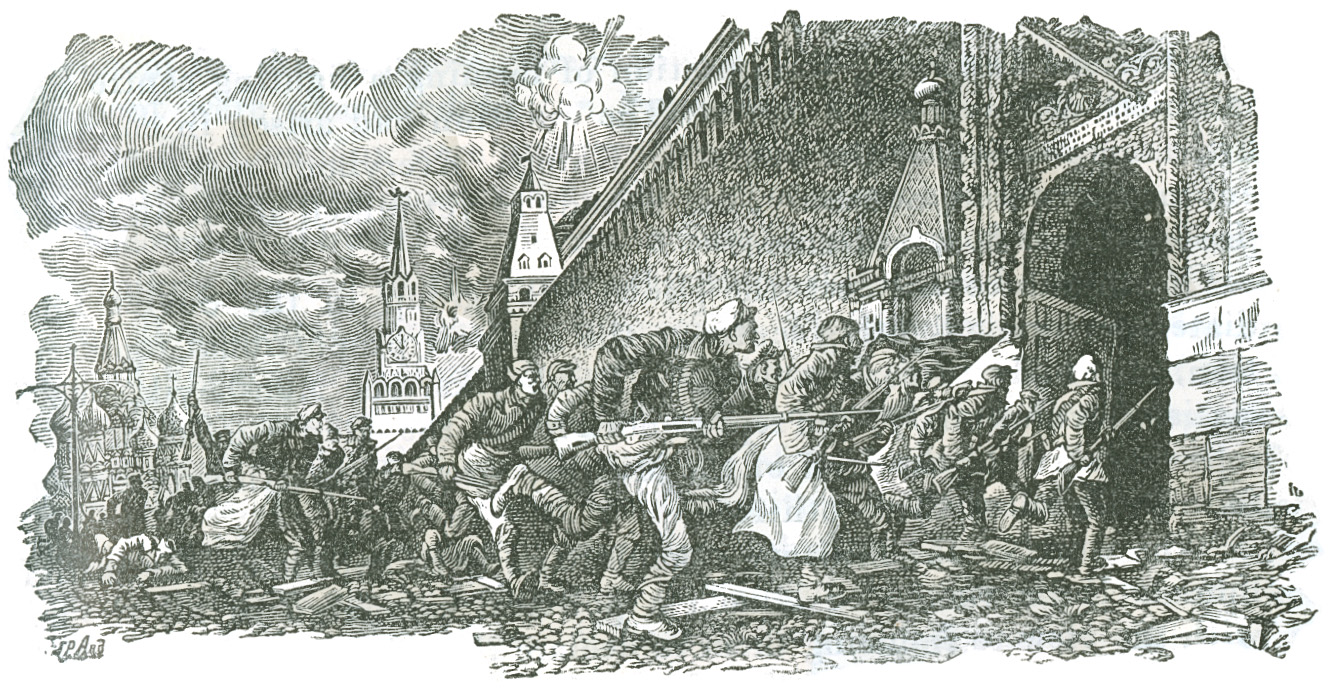

The soldiers had barely managed to occupy their different posts when a company of cadets from the Alexeyevsky Military School arrived from the direction of the Red Gate and turned towards the entrances at the General Post Office. The guard at the gates barred their way and held their rifles at the ready. In reply to the enquiry made by the astonished officer the men stated that the premises were guarded by the 56th Regiment. The officer telephoned to Military Area Headquarters and reported what had happened. As it transpired later, Area Headquarters was already aware of the revolution in Petrograd and was in its turn taking urgent measures. Its first object was to occupy the Central Telegraph Office, but in this it was foiled by the arrival of the revolutionary soldiers before the cadets. Colonel Ryabtsev, the Commander-in-Chief of the Moscow Military Area, was obliged to recall his cadets. The revolutionary patrols remained on guard.

After 1 p.m., while the soldiers were hastening to the Central Telegraph Office, a conference of representatives of all the party groups, including the Bolshevik group, was held in the premises of the Moscow Soviet. Colonel Ryabtsev was also present. Rudnyev, the Mayor of Moscow, a Socialist-Revolutionary, greatly excited, reported on the situation in Petrograd. After this a resolution was adopted which was to be submitted in the name of the Bureau representing all groups, to the joint meeting of the two Moscow Soviets which had been postponed until 3 p.m. This resolution read:

“For the purpose of restoring revolutionary order in Moscow and of guarding against all counter-revolutionary attempts, a provisional democratic body is to be set up consisting of representatives of the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, the City Council, the Zemstvo Council, the All-Russian Railwaymen’s Union and the Union of Post and Telegraph Workers.”[2]

Smidovich and Ignatov, the Bolshevik representatives on the Executive Committee, raised no objections to the formation of such a body. The only point of difference was the proportion of representation. Rudnyev insisted that the City Duma should have a majority of representatives, while Smidovich and Ignatov insisted that the Soviets should have the majority.

This resolution, however, ran counter to the proposal of the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party that the Soviets should form a fighting centre. By agreeing to Rudnyev’s proposal, the Bolshevik representatives at this conference took the line of negotiating with the compromisers.

The joint session of the two Soviets was not opened until 6 p.m. The Main Hall of the Polytechnical Museum where the meeting took place was crowded with deputies. Everybody had heard about the insurrection in Petrograd, but the reports were contradictory. Some said that the Provisional Government had been overthrown; others said that troops had been called from the front. The deputies gathered in groups, excitedly discussing the alarming news. At last Smidovich, the chairman, mounted the platform and opening the meeting said:

“Comrades. The course of the great revolutionary events which we have witnessed during the past eight months has brought us to the most revolutionary and, perhaps, the most tragic phase.”[3]

These words electrified the audience. All eyes were riveted on the speaker. Everybody was on tenterhooks, waiting to hear the answer to the vital question as to whether the insurrection had been successful. Continuing, Smidovich said:

“The information at our disposal does not enable us to say with certainty whether it will reach successful consummation. . . . Today we shall discuss the question of forming a new governmental centre in Moscow, a revolutionary governmental centre. . . .”[4]

In spite of the decision adopted by the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party, of which he was already aware, he pleaded for a unanimous decision on this question and referred to the draft resolution which had been adopted at the conference of representatives of all the party groups in the Soviets in favour of forming a coalition organ of government in Moscow.

When the chairman had finished his opening remarks telegrams announcing the insurrection in Petrograd were read amidst tense silence. The telegrams were very brief, but they left no doubt about the fact that the insurrection had been successful. Following this, the Menshevik Isuv reported on the decision which had been arrived at by the conference of representatives of all the party groups on the question of forming a coalition organ of government. This decision was obviously at variance with the nature of the events in Petrograd. The Bolsheviks called for an adjournment.

At a meeting of the Bolshevik group the draft of this “compromise” resolution was severely criticised. The Bolshevik representatives of the Executive Committee of the Soviet were told that the resolution they had voted for not only ran counter to the line of the Bolshevik Party and to the decision of the Moscow Committee, but was likely to render a bad service to the insurgent workers in Petrograd.

This “compromise” resolution was rejected by an overwhelming majority and the following decision was adopted:

“The Moscow Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies shall at today’s general meeting elect a revolutionary committee of seven.

“This revolutionary committee shall have power to co-opt representatives of other revolutionary democratic organisations and groups, subject to the sanction of the general meeting of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. The elected revolutionary committee shall begin to function forthwith with the object of rendering all possible assistance to the Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.”[5]

The meeting of the Soviet was resumed. The delegates filed into the hall.

The Bolshevik group called upon the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies to be with the workers and soldiers of Petrograd in this critical moment. Whoever failed to perform this duty would be a traitor, they said.

“Demagogy!” shouted the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries.

“Don’t burn your boats!” shouted the Menshevik Isuv. “Don’t break up the democratic front on the eve of the convocation of the Constituent Assembly! . . .”[6]

The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks loudly protested against the proposal to set up a Military Revolutionary Committee. They tried to scare the workers with the bogey of isolation and threatened that the counter-revolutionary organisations would come into power. As against the proposal to form a Military Revolutionary Committee they proposed that a “democratic body” be set up on the lines of the resolution adopted by the conference of party groups.

When the various groups had made their declarations the Soviet decided to put the matter to a vote without further discussion. A proposal was made to take the Bolshevik resolution first, but the Mensheviks insisted that theirs should be taken first. A commotion arose in the hall. Several delegates protested against the efforts of the Mensheviks to drag out the meeting. A number of delegates demanded the floor to make proposals. The Socialist-Revolutionaries consulted with each other in whispers. Suddenly their spokesman got up and announced that they would take no part in the voting. It was noticeable from the platform that the Socialist-Revolutionary group in the hall had greatly dwindled; individually and in groups, they were stealthily leaving the meeting.

Observing this flight, the Bolsheviks demanded a roll call. At this pandemonium broke loose. The Socialist-Revolutionaries remaining in the hall shouted that they would withdraw from the meeting entirely.

At last the voting was proceeded with.

By a vote of 394 against 106, with 23 abstentions, the meeting adopted the Bolshevik resolution. The “compromise” resolution polled only 113 votes. The Socialist-Revolutionaries refrained from voting.

After the count the Mensheviks made the following declaration:

“It is our duty and obligation to guard to the end the working class and the Moscow garrison from the reckless, dangerous path, which you [the Bolsheviks—Ed.] are taking. For that reason we shall join this body, but we shall do so not for the object which you are pursuing, but for the purpose of continuing the work of exposure which we have been performing in the Soviet in order to mitigate all the fatal consequences that will fall on the heads of the proletariat and the soldiers of Moscow.”[7]

Two lines of policy—the Bolshevik and the compromising line—were in conflict at this meeting of the Soviets on October 25: the first was that of taking action to support the Petrograd proletariat and garrison; the second was that of betraying the proletarian revolution on the plea of waiting for further developments in Petrograd.

A Military Revolutionary Committee was elected consisting of four Bolsheviks and three Mensheviks. The Socialist-Revolutionaries refused to sit on this Committee.

Unlike the Military Revolutionary Committee in Petrograd, the Moscow body contained Mensheviks, who were actually the spies of the bourgeoisie. Moreover, together with devoted revolutionaries like Usiyevich, it contained defeatists like Muralov, who was subsequently shot for high treason. A committee of such a composition could not but have a harmful effect upon the leadership of the insurrection.

The newly elected Military Revolutionary Committee immediately left the Polytechnical Museum for the Moscow Soviet and started work. Here, too, on the night of October 25, the Party fighting centre took up its headquarters.

It soon became known where the Socialist-Revolutionaries had gone to on leaving the meeting of the Soviet. At about 9 p.m., three hours after that meeting had started, a special meeting of the City Duma was held, at which, unlike the meeting of the Soviet, anxiety and nervous anticipation prevailed. The Constitutional Democrats, Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks predominated. The solemnity which the Constitutional Democratic professors tried to introduce in the meeting faded away. The deputies fidgeted nervously, exchanged news, flitted from one party group to another, and crowded around the various party leaders as they entered the hall.

Rudnyev, the Mayor of the City, addressed the meeting. He had just been in communication with the Winter Palace by telephone, and Nikitin, the Menshevik Minister for the Interior, had managed to inform him that the Bolsheviks had called upon the Provisional Government to surrender. The government had instructed him, Rudnyev, to organise resistance in Moscow.

In a melancholy, tragic voice he said:

“The issue at stake is whether the government is to be overthrown and power seized by a certain party—the Bolsheviks. We are witnessing the last hours of the Provisional Government. The government is in its death throes.”[8]

Rudnyev then reported on the events in Petrograd. The Central Telegraph Office had been captured by the Bolsheviks. The railway stations were in the hands of the insurgents. The Pre-parliament had been dispersed by a detachment of sailors and soldiers. Preponderance of strength was on the side of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, but the Provisional Government was still holding on.

“Fifteen minutes ago,” continued Rudnyev, “Nikitin, the Minister for the Interior, reported the following: Half an hour ago, two soldiers from the Military Revolutionary Committee had come to him with a statement that the Provisional Government was regarded as deposed. If the Provisional Government agreed to regard itself as deposed its safety would be guaranteed. Nikitin had replied that the government was of the opinion that it had no right to retire.”[9]

These remarks were greeted with loud applause on all sides, except from the Bolsheviks and Unionists. The panic-stricken deputies saw a ray of hope, but it vanished in an instant. Rudnyev proceeded to deal with the situation in Moscow. The Central Telegraph Office had been occupied by the 56th Regiment. A number of other acts of seizure were being committed. All this was being done in the name of the Soviet, but actually it was being directed by the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party.

“The Moscow City Duma,” he said in conclusion, “may not possess physical force, but it is the sole and supreme authority in the city and cannot sanction what is now taking place in Petrograd. Moreover, a concrete duty devolves upon it—to ensure the safety of the population of Moscow, to whom it is responsible.”[10]

Rudnyev proposed that the City Duma should set up a united body to be known as the “Committee of Public Safety” for the purpose, as he explained, of protecting the population. He delivered the last part of his speech amidst intense silence, which continued long after he finished speaking. Nobody asked for the floor. At last, the Constitutional Democrat Shchepkin, who subsequently became the leader of one of the biggest plots against the Soviet Government, got up and proposed that the Duma should first of all hear “. . . those who are responsible for the terrible events that are happening in the country, those who occupy the left benches.”[11]

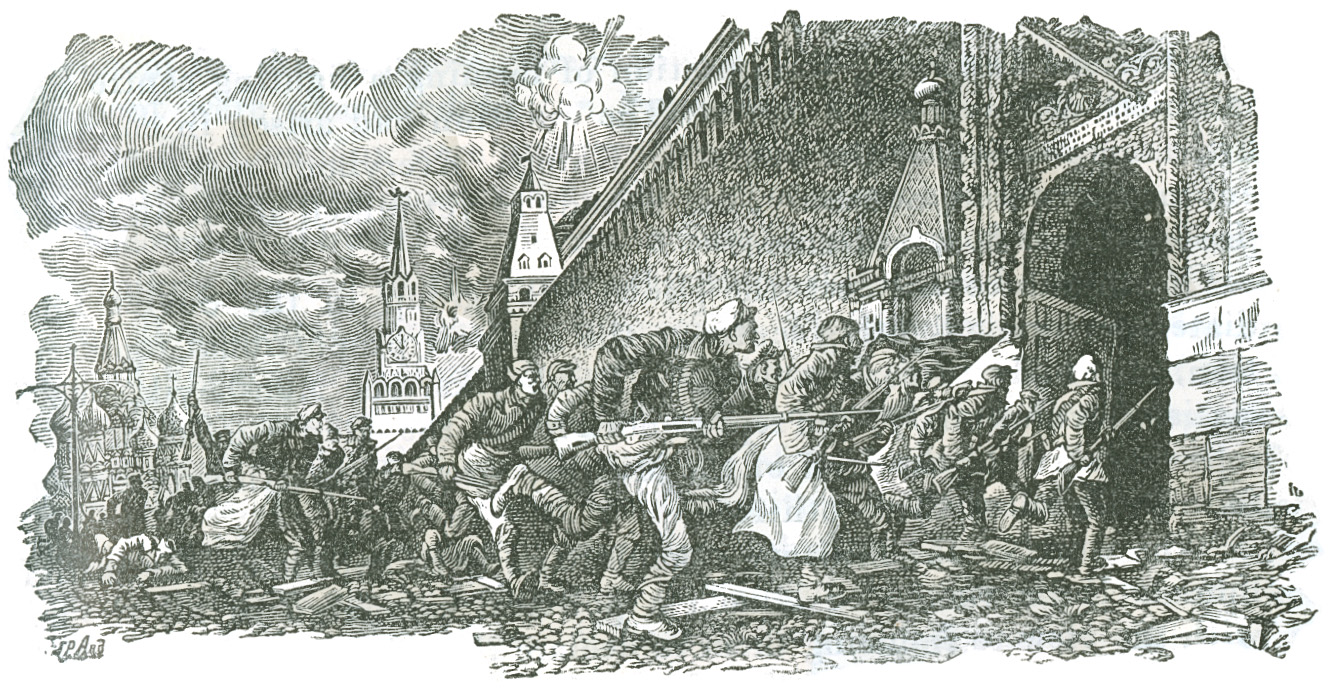

The veteran Bolshevik I.I. Skvortsov-Stepanov replied in a clear, calm voice, that reverberated throughout the hall:

“When the Moscow State Conference was held the trade unions decided to react to it by holding a demonstration. At that time the Mayor challenged the right of the workers to demonstrate and described it as an anarchistic demonstration by the minority. Six weeks have passed and the anarchistic minority now proves to be the majority. This has been definitely proved by the District Duma elections. In whose name does the Mayor speak? In the name of those who were elected on June 25, but not in the name of the present majority. Now you are the minority.”[12]

The public gallery and the Bolshevik members in the hall greeted this statement with an outburst of applause. The Constitutional Democrats fumed with rage. The Socialist-Revolutionaries glanced at each other in silence.

“The Duma,” continued Stepanov, sharply raising his voice, “no longer represents the population. In the name of the future of our country we speak boldly and emphatically. Power is being seized not by an insignificant minority, but by the representatives of the majority in the country. This is proved by the facts. The Telegraph Office, the Smolny Institute, the railway stations, the State Bank and a number of other institutions have been occupied, and this was resisted only by a few score of people. This proves that the people are not with the Provisional Government. It is a Provisional Government not by the will of the people, but by the grace of Rodzyanko. Pass your resolution. We shall not take part in the voting on it. But bear in mind the responsibility that you are taking upon yourselves.”[13]

Skvortsov-Stepanov’s speech caused dismay in the ranks of the social-compromisers and evoked feeble protests. The representatives of the Socialist-Revolutionaries stated that “the entire peasantry is opposed to insurrection,” that “the Bolsheviks have not a majority in the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies,” that “the Soviets of Workers’ Deputies are not the entire proletariat. . . .”

Astrov, the spokesman of the Constitutional Democrats, the second largest group in the City Duma, called for unconditional support for the Provisional Government. Himself a monarchist who, with Milyukov, had pleaded for the preservation of the autocratic rule of the Romanovs, he now compared the capture of power by the Soviets to . . . a reversion to the monarchy.

The Mensheviks, in long and rambling speeches, accused the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies of having taken a wrong and false step. They promised support for a body consisting of representatives of all the democratic organisations, but if this body took measures of repression against the workers they would withdraw from it.

The Mensheviks were in a state of utter panic and confusion. Some of them said that they would oppose the Provisional Government if it resorted to the death penalty. Others echoed the Constitutional Democrats in calling for whole-hearted support for the Provisional Government, even if that meant resigning from the Menshevik group.

These dull and dreary speeches went on endlessly, each group trying to throw the blame on the other. Amidst the din of this mutual recrimination the Bolsheviks withdrew from the meeting and hastened to the districts where urgent work awaited them.

The departure of the Bolsheviks convinced the remaining members that they were simply wasting time. The debate was closed. At about midnight a long resolution was adopted calling upon all and sundry to rally around the City Duma and to resist the Bolsheviks.

On Rudnyev’s motion the Duma formed a “Committee of Public Safety” consisting of representatives of the Duma, the Moscow Uyezd Zemstvo Council, the Executive Committees of the Soviets of Soldiers’ Deputies and Peasants’ Deputies in which the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks were in the majority, the Staff of the Moscow Military Area, the Union of Post and Telegraph Employees and the Railwaymen’s Union.

The Mensheviks elected their representatives to the “Committee of Public Safety” as well as to the Military Revolutionary Committee.

The Socialist-Revolutionaries refused to serve on the Military Revolutionary Committee, but they unreservedly supported the “Committee of Public Safety.” This explains the riddle of their refusing to take part in the voting and their withdrawal from the meeting of the Soviets. They had hurried off to the counter-revolutionary Duma.

Immediately after it was formed, the “Committee of Public Safety” issued an appeal to the City Dumas all over Russia to support the Provisional Government and to organise local Duma Committees.

The Chief Committee of the Union of Cities, of which Rudnyev was the chairman, telegraphed to all urban and rural local government bodies urging them immediately to elect delegates who were to hold themselves in readiness to assemble, as soon as the signal was given, for the purpose of organising and supporting the Constituent Assembly. The object of this appeal was to offset the Second Congress of Soviets by a congress of urban and rural local government bodies.

The “Committee of Public Safety” set to work at once. On Colonel Ryabtsev’s instructions the cadets occupied the Duma premises and also the Riding School opposite the Troitsky Gate of the Kremlin. They wanted to enter the Kremlin, but the soldiers on guard barred their way.

At midnight on October 25, while the leading body of the counter-revolution was being formed in the City Duma, a meeting of the Military Revolutionary Committee was held. The Mensheviks resorted to obstruction by making long and meaningless speeches. Ryabtsev’s cadets were already marching through the streets and it was necessary to take urgent and energetic action, but this was the moment the Mensheviks chose to move that the first item of business should be the question of co-opting representatives of other organisations to the Military Revolutionary Committee. This proposal was rejected. The Committee sent a guard composed of men of the 56th Infantry Regiment to the State Bank in Neglinnaya Street. The occupation of the railway stations was entrusted to the Railwaymen’s Military Revolutionary Committees. The following telephone message was sent to all the districts:

“Meet, elect a district revolutionary centre, decide what to occupy in your district (offices, public buildings, etc.), immediately arm (occupy arms depots), establish contacts with the revolutionary centre of the Soviet and the Party.”[14]

A company of the Cycle Battalion was called out to guard the Moscow Soviet. In accordance with the instructions of the Party Centre, the Military Revolutionary Committee sent soldiers to close down the bourgeois newspapers Russkoye Slovo, Utro Rossii, Russkiye Vedomosti and Ranneye Utro. By 4 a.m. the printing offices of these newspapers were sealed.

An order was issued to the garrison informing it of the insurrection in Petrograd and calling for support for it. The Military Revolutionary Committee declared:

“1. The entire Moscow garrison must immediately prepare for action. Every military unit must be ready to come out at the first word of command of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

“2. No order or instruction issued by any body other than the Military Revolutionary Committee is to be obeyed unless counter-signed by the Committee.”[15]

Obviously this was not enough. The army units should have been called to the Soviet and instructed to occupy the Kremlin and other government buildings. Comrade Yaroslavsky proposed that the Riding School should be occupied at once so as to safeguard the approaches to the Kremlin, but this proposal was not accepted.

A special commission was set up to organise and direct the work in the districts. This commission requested all the District Soviets to appoint persons to act as the Commissars of the Military Revolutionary Committee in the various districts.

These Commissars were instructed not to wait for orders, but immediately, on their own authority, to appoint Commissars over all the army units and also Commissars of the militia and post offices, and with the aid of the Red Guard to organise the protection of the districts.

The Military Revolutionary Committee was in constant session. Telephone messages were received from all the districts in the city asking for instructions and enquiring whether military units were needed, and where they were to be sent. The answers to these enquiries were indefinite, however. It was evident that the Military Revolutionary Committee had no plan of action for the insurrection, and was not displaying the necessary determination.

The question that excited the workers most was that of obtaining arms. Ryabtsev had taken the precaution to deprive the soldiers of their rifles. All night long delegates from the regiments and from the Red Guard came to the Soviet in quest of arms. The districts sent their Commissars with strict instructions not to return without arms.

There was a large quantity of arms in the Kremlin arsenal. The Military Revolutionary Committee appointed E. Yaroslavsky Commissar of the Kremlin. O. Berzin was recalled from the Post Office and appointed Commissar of the arsenal to supervise the issue of arms. The Commissars were instructed to go to the Kremlin and were warned that in the morning the districts would be sending their messengers for arms.

In the Kremlin were quartered a battalion and one company (five companies in all) of the 56th Regiment, which was pro-Bolshevik, and a detachment for the arsenal. The Kremlin was also the headquarters of Colonel Ryabtsev, the Commander-in-Chief, and of the Staff of the Ukrainian units, and of a large number of officers who had their quarters there. They had two armoured cars at their command.

Measures had to be taken against the hostile forces in the Kremlin, but the Military Revolutionary Committee did not settle this question. True, jointly with the Party Centre, it passed a resolution urging the necessity of increasing the Kremlin garrison and recommending for this purpose the 193rd Infantry Reserve Regiment which was quartered in Khamovniki and upon whose loyalty to the Soviet it had every reason to rely.

On the night of October 25, E. Yaroslavsky, the Commissar of the Kremlin, went to Khamovniki to convey the order of the Military Revolutionary Committee. The members of the Regimental Committee on duty quietly mustered a company and by 5 a.m. it arrived in the Kremlin.

Berzin appeared at the arsenal and the guard escorted him to the apartment of Major-General Kaigorodov, the chief of the arsenal. The stores were opened and the company from the 193rd Regiment was armed.

Early in the morning of October 26, the District Party Centres and Military Revolutionary Committees took care first of all to send Red Guards to the Kremlin with official requests for arms, but only three motor trucks managed to reach the arsenal. The rest were held up by cadets who, the night before, had occupied the Riding School opposite the Troitsky Gate entrance to the Kremlin. It transpired that Ryabtsev had learned that a company from the 193rd Infantry Reserve Regiment had been brought in and had ordered the cadets to surround the Kremlin. The three trucks that did get through were captured as they left the Kremlin loaded with arms.

The troops of the Military Revolutionary Committee were thus left unarmed. The districts did not receive a single rifle from the arsenal.

In the districts the workers were waiting in tense expectation for the order to start the insurrection. On the night of October 25, a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Zamoskvorechye District Soviet was held at which a Military Revolutionary Committee of five was elected. This Committee appointed a Commissar to act as the representative of the Moscow Military Revolutionary Committee.

On the morning of October 26 the Zamoskvorechye Military Revolutionary Committee occupied the district militia station and removed the government Commissars. Red Guards were called to the Headquarters of the Committee and ordered to occupy the electric power station of the “1886 Company.” This protected the Zamoskvorechye District from the side of the Moscow River Bridge. Moreover, it enabled the Committee to deprive the districts occupied by the Whites of electric light.

The Headquarters of the Military Revolutionary Committee was strongly guarded against a likely attack by the Whites. It was anticipated that the students of the Commercial Institute would try to seize the premises. Men were constantly on duty also at the District Committee of the Bolshevik Party.

In the evening of October 25, a joint meeting of the Khamovniki District Soviet and the active Party workers in the factories in the district was held in the Students’ Dining Rooms at No. 6 Devichyi Field. Enthusiasm ran high. Delegates reported that the masses were ready for action. Late that night a Military Revolutionary Committee was elected. The first thing it did was to take stock of the arms available. It found fifteen old rifles in the premises of the District Committee of the Bolshevik Party, about a dozen others in different factories, and several revolvers. These were all the weapons available to arm a hundred Red Guards! There were in reserve a few hand grenades which had been clandestinely manufactured by the workers of the Kauchuk Rubber Factory. An appeal was then made to the 193rd Regiment, but it was found that Ryabtsev had taken away nearly all their rifles. About a dozen rifles and a couple of hundred cartridges were obtained from the “disciplinary” company. By order of the Military Revolutionary Committee guards were posted at the factories. A first-aid centre was set up in the Students’ Dining Rooms.

On the morning of October 26, the Sushchevsko-Maryinsky Soviet summoned a score or so of Red Guards from the Ordnance Works. All the morning men came to the Soviet from the factories to hear the latest news. In the afternoon a special meeting of the Soviet was held at which a Military Revolutionary Committee was elected.

In the Presnya District a Revolutionary Committee was formed on October 25. In the Railway District, too, a Revolutionary Committee was formed that day, and at night one was formed in the Sokolniki District. In the other districts of Moscow they were formed either on the 25th or the 26th.

In the districts the workers began to confiscate arms from counter-revolutionaries, and in many cases Red Guards, carrying rifles without cartridges, disarmed officers and cadets.

But not until the militia stations were occupied were the districts able to proceed with the confiscation of arms on a large scale, not only in the streets of Moscow, but also in the apartments of officers and the bourgeoisie. The occupation of the militia stations all over the city took place on October 26 almost without resistance. The whole affair reduced itself to dismissing the old Commissars and appointing new ones. Only the Headquarters of the City Militia remained uncaptured. Subsequently, these premises served the cadets as one of their most important strongholds in their attack on the Moscow Soviet.

On October 26 the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party issued a manifesto to the workers and soldiers calling upon them to start the offensive. At 4 p.m., however, the District Military Revolutionary Committees received a telephone message from the Moscow Military Revolutionary Committee ordering them to refrain from offensive operations. Everybody wondered what had happened.

[1] The Moscow Party Archives, Minutes of Proceedings of the Moscow Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.

* Formed by soldiers from Smolensk who were serving in the Moscow Region . . . Trans.

[2] The Moscow Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 94 of the Moscow Soviet, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 25, folio 15.

[3] “The Soviet of Workers’ Deputies.” “The Meeting of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies of October 25,” Izvestia of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, No. 197, October 26, 1917.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Moscow Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 94 of the Moscow Soviet, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 25, folio 24.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “The Meeting of the City Duma of October 25,” Izvestia of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, No. 197, October 26, 1917.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] A. N. Voznesensky, Moscow in 1917, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, p. 151.

[12] "The Meeting of the City Duma of October 25,” Izvestia of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, No. 197, October 26, 1917.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund No. 1, File No. 2, p. 530.

[15] “The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Izvestia of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, No. 197, October 26, 1917.

Previous: The Suppression of the Kerensky-Krasnov Mutiny

Next: Negotiations with the Whites