The only defenders of the Provisional Government were the cadets. The Soviet Government was defended by the entire working-class population of the red capital. During those days the Petrograd workers displayed supreme heroism, unprecedented enthusiasm and selfless devotion to the cause of the proletarian revolution. Their courage and self-sacrifice compensated for the defects in organisation, which were inevitable in the first days of the new regime.

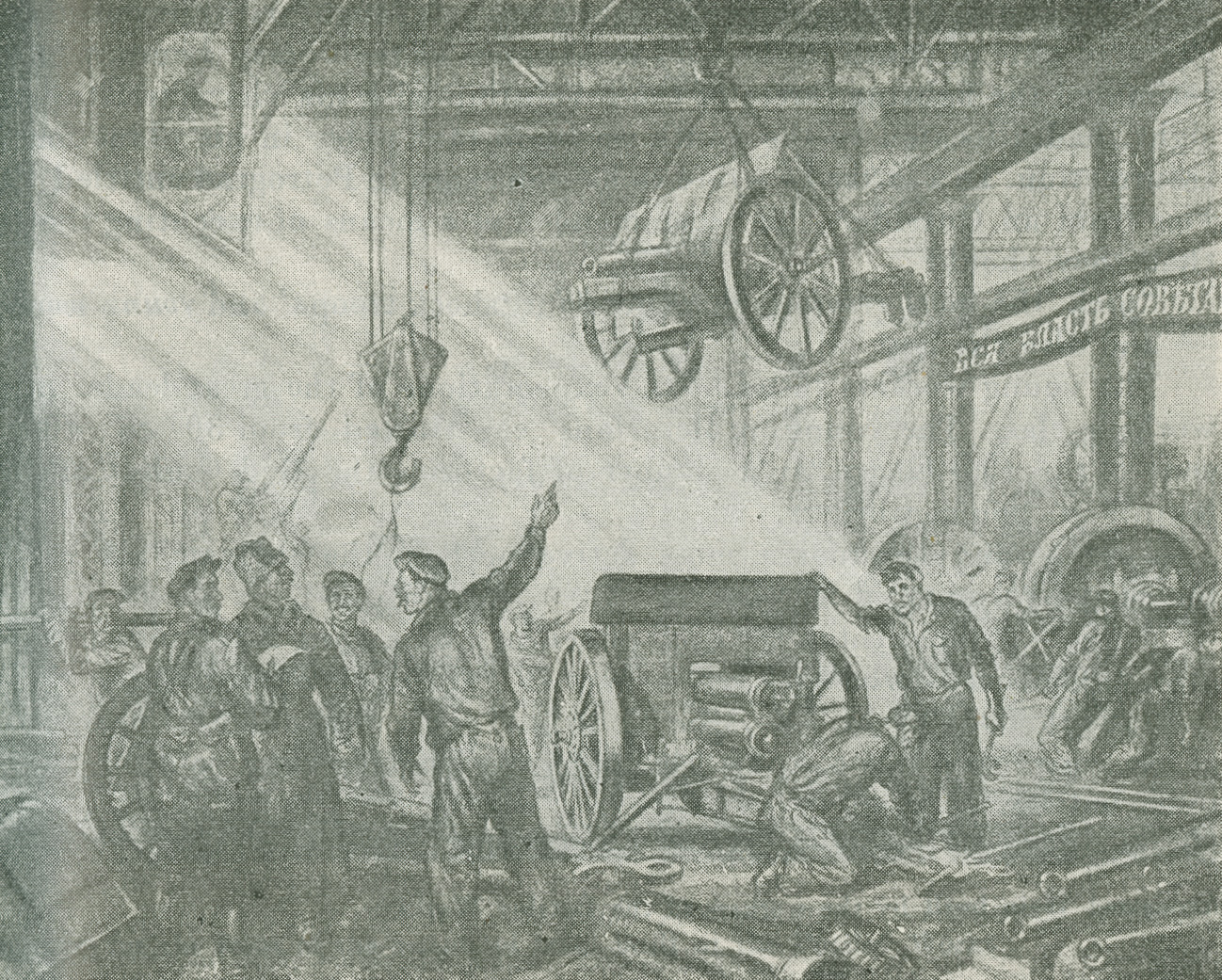

The workers of the different factories and mills vied with each other in heroism. Some, in response to the call of the Military Revolutionary Committee, took up arms and went to the front. Others worked on fortifications at the approaches to Petrograd. The district staffs of the Red Guard formed armed workers’ detachments and dispatched them to Pulkovo. In the factories the production of war material went on day and night. The workers repaired armoured cars, assembled guns and fitted up armoured trains. This is illustrated by the following statement subsequently made by the Commissar of the Putilov Works:

“During Kerensky’s counter-revolutionary adventure, I, at the request of the Military Revolutionary Committee, dispatched to Krasnoye Selo and Gatchina, and also to the positions at Pulkovo-Alexandrovka:

“2 armoured cars;

“4 motor trucks mounted with four anti-aircraft guns;

“4 trucks loaded with shells;

“2 Red Cross vans which we ourselves had equipped with stretchers, medical supplies, etc.;

“2 field kitchens, which we had also fitted up.

“We dispatched together with gunners, gun crews and escort:

“4 forty-two bore guns, and 19 three-inch guns.

“I myself went to the forward positions with a workers’ unit 200 strong and remained there five days and nights. Very often mechanics were sent to the positions to repair guns. Over 500 Putilov workers and 50 carpenters were sent to the trenches with all the tools they needed.

“The Putilov Works supplied the men taking part in operations with fuel, gas-driven automobiles, etc. We carried wounded in passenger cars from Krasnoye Selo and Gatchina until the arrival of the Red Cross unit.

“All damaged motor trucks were immediately repaired in our automobile shop, which was kept running day and night, and returned to the Headquarters of the Revolutionary Committee the moment repairs were completed.”[1]

The Putilov unit of the Red Guard consisted of thousands of picked revolutionary fighters. In the October days alone the Putilov workers received over 2,000 rifles, of which 1,212 were issued to the works proper, and 804 to the Putilov shipyard. About half of the youths employed in the Putilov Works joined the Red Guard. A large number of the men served in the technical forces, some as drivers, others in the artillery. Twenty-two truck drivers of the Putilov Works were placed at the disposal of the Military Revolutionary Committee and sent to the Krasnoye Selo-Tsarskoye line. Later, the Chief of Staff of the Gatchina unit issued a certificate couched in terse, military terms stating that they had “conscientiously performed their duties and are now returning to the Putilov Works.”[2]

A tense atmosphere prevailed in the working-class districts of Petrograd in those days. The workers flocked to the district headquarters to enrol in the Red Guard. Many brought reports about suspicious houses where army officers gathered. The workers of the Franco-Russian Works demanded that drinking dens like the “Columbia,” “Mayak” and “Svoboda,” where the declassed elements were supplied with free liquor by the counter-revolutionaries, should be closed.

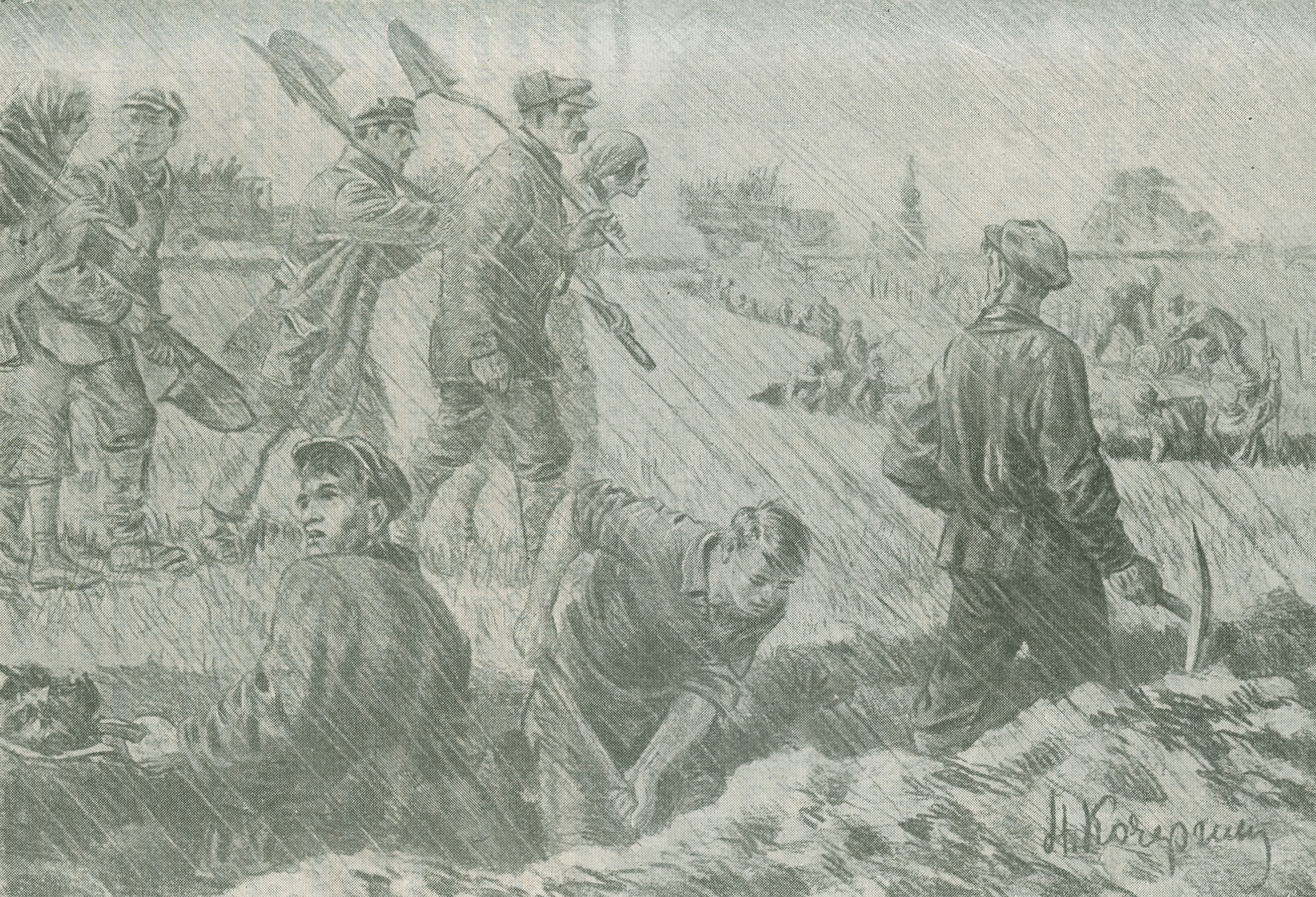

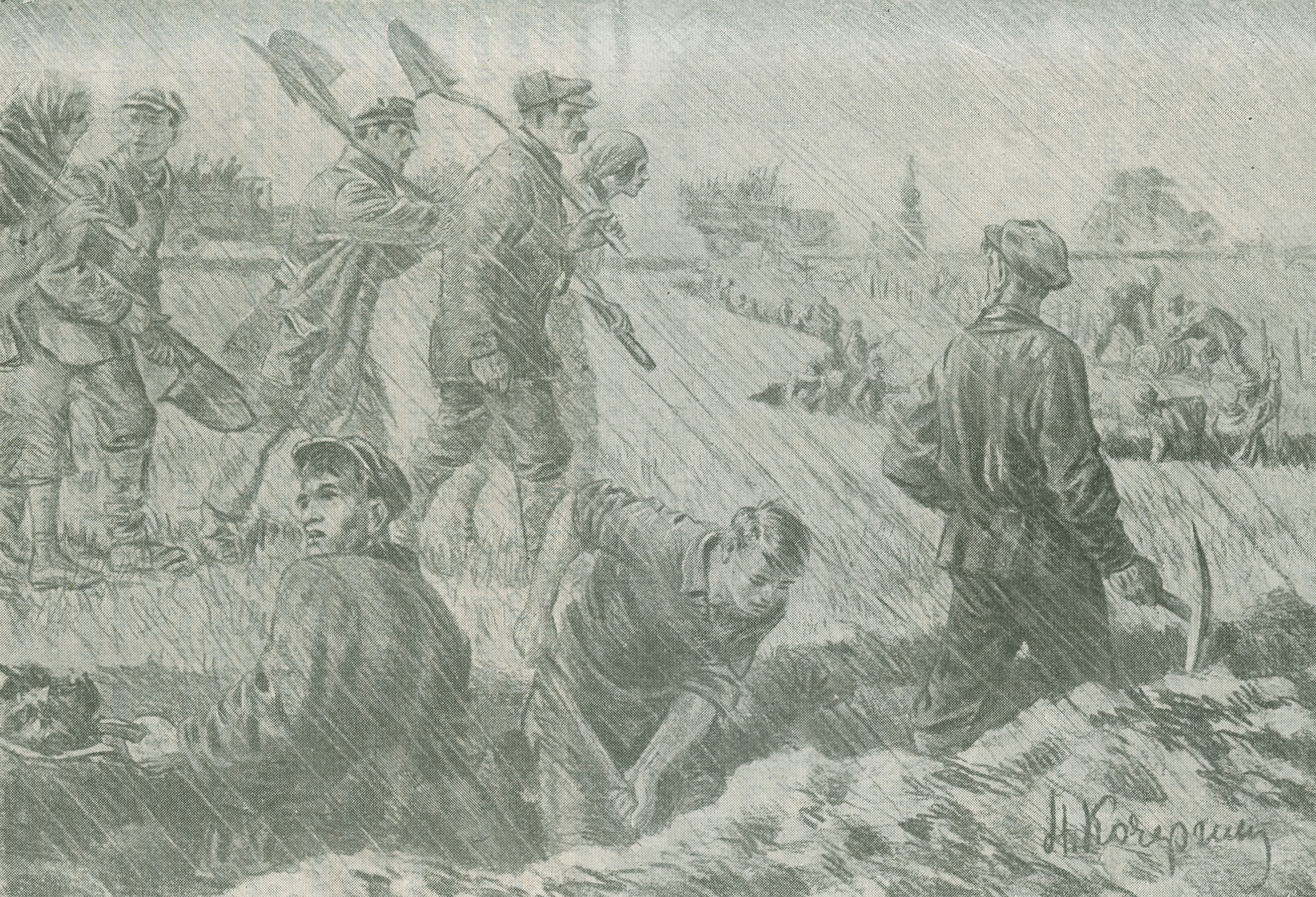

One after another columns of armed worker volunteers marched down the Bolshoi Sampsonievsky Prospect, in the Vyborg District, carrying red banners and streamers on which fighting slogans had been hastily inscribed. The columns reached the premises of the District Soviet and District Staff Headquarters, which only recently had housed the “Quiet Valley” tavern. The rooms were noisy and crowded. Here the newly elected officers received their credentials. Men without arms were supplied with rifles and those who were badly clothed received equipment. Military instructors formed detachment after detachment which, amidst the strains of the martial music played by the band of the Moscow Regiment, marched off to Tsarskoye Selo Station, to be dispatched forthwith to Pulkovo. The workers of the Pipe Works, Siemens-Halske and Possel’s came straight from their work to the commandant requesting that they be given arms and sent to the firing line. During the day, 3,000 rifles were issued, and still workers came pouring in. There were not enough rifles to go round, so the workers took picks and shovels and went off to dig trenches.

The road to Pulkovo was lined with an endless column of revolutionary detachments marching in the pouring rain. They were overtaken by motor trucks filled with armed workers. Old men, and even youths, hastened to the front. The trains to Gatchina were packed, and still men struggled to get in. Red Guards and sailors clung to the roofs and steps of the railway cars. There was a perfect rush to the place from where the dull booming of guns was heard.

At the front, thousands of men and women toiled in the wet and mud, digging trenches and erecting barbed-wire entanglements. Ahead of them, Red Guards, lying in hastily dug shallow pits, peered vigilantly in the direction of the enemy. From the rear, reinforcements arrived at a brisk and confident pace.

The District Committees called upon the working women in the factories and mills to volunteer as nurses, and everywhere small first-aid units were formed.

In the course of one night over two hundred women at Siemens-Halske enrolled, procured the necessary medical supplies themselves, and at once went off to the front.

The working women of Petrograd not only rendered first aid to the wounded, but participated in the great struggle in many other ways. At the Army Medical Supplies Factory the women procured provisions, cooked them in the kitchens of the factory dining rooms and took the food to the front which was not far away. The men, hungry and cold, eagerly surrounded the motor trucks on which the food had been brought, and from them the women distributed loaves of bread, boiled meat and hot potatoes which had been kept warm by the sheepskin coats in which the containers had been wrapped.

During those October days the young workers fought with the enthusiasm characteristic of youth in the very front ranks of their class. Lenin, who had estimated the fighting forces of the revolution with his characteristic foresight, had allocated to the youth an important place in his plans for the insurrection. In a letter he wrote to his comrades in Petrograd entitled “Advice from an Outsider” he recommended as a means of executing the plan that they should

“pick the most resolute elements (our ‘shock troops’ and young workers, and also the best sailors).”[3]

The young workers justified the expectations of the great leader of the working class. The young proletarians constituted from 30 to 40 per cent of the Red Guard. In a number of factories the Red Guard consisted mainly of young workers.

These young men took a most active part in the struggle against the forces of Krasnov and Kerensky.

An enquiry instituted in the summer of 1932 among 2,274 former Petrograd Red Guards who had taken part in the October insurrection showed that about 900 of them, i.e., nearly 40 per cent, were under 23 years of age at the time. Such was the part played by the working-class youth in the October battles.

This was realised also by the enemies of the Soviet Government who distorted the true significance of these great events. On October 29, the Menshevik newspaper Yedinstvo published an article entitled “A Biblical Crime,” in which the author asserted that Red Guard units consisting of mere children, boys of 15 or 16, had been sent to fight Kerensky’s troops:

“They marched along the streets in a crowd of several hundred, or perhaps a thousand, in the direction of the City Gates.”[4]

In the bitter struggle for a brighter future the Petrograd proletariat, young and old, was united. Fathers, mothers and children—members of the indivisible proletarian family—marched in serried ranks to fight for their Soviet Government.

October 29 was a critical day for the Military Revolutionary Committee. Directed by Lenin and Stalin, this young and not yet consolidated organ of the new government, was suddenly put to a severe test.

Already at daybreak it was learned that a mutiny had suddenly broken out in the city and that the cadet schools had risen in revolt against the Soviet Government. At 5 a.m., when the lights in the rooms of the Military Revolutionary Committee were still burning, the telephone rang sharply. The weary attendant picked up the receiver and heard a distant voice speaking excitedly. It was the member on duty of the Regimental Committee of the Officers’ Electrical Engineering School. He said:

“About sixty cadets, evidently from the Nikolayevsky School, have appeared in Inzhenernaya Street. They are armed. As they go along they stop soldiers and urge them to join them. They are probably making for the Mikhailovsky Riding School.”[5]

At 8 a.m. all doubts were dispelled. The following message was received:

“The Mikhailovsky Riding School has been occupied by cadets. The machine-gunners of the Lithuanian Regiment are on their way there.”[6]

Then came more bad news:

“The cadets have advanced from the Mikhailovsky Riding School with armoured cars and have occupied the Central Telephone Exchange. There is not a single officer in the Riding School. The machines were left there.”[7]

“Vladimirsky School. At night those who were asleep were captured and the mixed company stationed on Bolshoi Prospect was disarmed. Firing is going on in the vicinity of Bolshaya Grebetskaya Street.”[8]

“In Shpalernaya Street cadets of the Engineering School are selling newspapers and pamphlets.”[9]

Armed forces were hurled against the rebels. The stormy night at last drew to a close and the grey, cheerless dawn peered through the rain-streaked windows, boding still greater evil than the preceding night. The rooms of the Military Revolutionary Committee were crowded and noisy with the stamping of rifle butts and the clicking of typewriters typing out orders, instructions, certificates and the minutes of special conferences. The voices of the men in leather coats and crumpled soldiers’ greatcoats—members of the Committee—were cracked and hoarse. Their eyes, hollow with lack of sleep, were ablaze. The rooms and corridors echoed with the tramping of crowds of armed workers, young and old, carrying rifles, their wan faces black with the grime of the factories; there were crowds of soldiers with cartridge belts strapped across their shoulders, and sailors with weather-beaten faces and hand grenades stuck in their belts.

Some demanded provisions or ammunition for their men. Others had come to report about the temper prevailing in their units, while others again had come for instructions, advice or assistance.

Outside, the rumble of automobile engines was heard. Motor-cyclists, their machines rattling like machine guns, dashed up to the entrance of the Smolny and quickly dismounting, hastened inside with dispatches.

These dispatches, of a most contradictory nature, came pouring in from all sides. At 3:20 p.m. a message arrived from the Putilov Works stating that rifle and gun fire was heard and anxiously enquiring whether measures were being taken.[10]

The following dispatch was received from the 1st Don Cossack Regiment:

“A delegation from Kerensky’s troops has arrived and is urging the regiment to join them. The regiment is beginning to waver.”[11]

Hordikainen, a resident of Tsarskoye Selo who had come all the way on foot, related:

“The town is occupied by Kerensky’s troops, most of whom are concentrated near the railway station. In all, Kerensky has about 5,000 men in the district. The soldiers are requisitioning from the peasants their cattle and all the provisions they can lay their hands on, merely giving them receipts in return. During the firing some local inhabitants suffered, and two or three children were killed. One shell burst in the garrison hospital. Some of the members of the Soviet, about eight of them, and some of the troops have remained in the town,” how many Hordikainen could not say.[12]

The telephone kept on ringing almost incessantly.

The commandant of the Soviet of the 1st City District reported that “at noon an armoured car opened fire on the premises of the Soviet.”[13]

Commissar Medvedev reported:

“The Ismailovsky Regiment is moving into position. Cyclists should be dispatched to Alexandrov Station.”[14]

A senior militiaman reported:

“A mass meeting is to be held on the Obvodny Canal. Exactly where it is to take place, and at what hour, has not been ascertained. Scouts should be sent out—I think the meeting will be a counter-revolutionary one.”[15]

Fighting had broken out in Petrograd and Kerensky was approaching with Cossacks. Night fell, and again the electric lights were put on. Far away the dull boom of artillery and the vicious rattle of machine guns were heard. The vast city was enveloped in a cold, damp mist, and nobody knew for certain what was going on beyond it. How was the fighting progressing? Who would gain the upper hand? People hung on to telephone receivers, with puckered brows, their faces gloomy and tense with anxiety. The cadets were still holding the Telephone Exchange. The Commissar of the guard of the State Bank reported that when he telephoned, the telephone girl replied that “a cadet was standing behind her” with a bayonet pointed at her “and therefore she could not connect him.”[16]

At last more cheerful news arrived, and the faces of the people who had been anxiously waiting lit up with joy.

9 p.m.

A report was received that the Commissars of the Tsarskoye Selo Railway Station who had been arrested by the cadets were now free.

10 p.m.

A message from the Petersburg District.

“The windows of many of the houses adjacent to the Pavlovsky School have been smashed as a result of the shelling of the school. Excitement is rife among the inhabitants. A riotous mood is growing and urgent measures must be taken. The District Committee proposes that glaziers be called to put in the windows, taking the glass from the extra winter frames. Moreover, it is necessary to place guards near the shops where the windows have also been smashed, otherwise there will be a riot.”[17]

10:55 p.m.

A telephone message from the Phoenix Works:

“The cadets of the Mikhailovsky Artillery School have surrendered. The arms are being taken away by the Staff of the Red Guard and the Moscow Regiment. One motor truck has already been loaded. The school is being searched.”[18]

10:55 p.m.

The following telephone message was received from the Revolutionary Staff at the Moskovskaya Zastava:

“We need ambulances, as many as possible. Many wounded. Cheers are heard in the direction of the Petrograd Chaussée. We also need artillery, for according to as yet unconfirmed information, Kerensky has an armoured train at his command.”[19]

This was the voice of the front. While suppressing the treacherous revolt of the cadets and taking care to maintain order in the city, the Military Revolutionary Committee could not for an instant forget that the enemy was at the approaches to Red Petrograd and that in the gloom of the misty night fierce fighting was proceeding and blood was flowing. At the meetings of the Committee, terse and resolute decisions were quickly arrived at:

Kerensky’s delegation which is agitating among the 1st Cossack Division is to be arrested.

Visitors to the Fortress of Peter and Paul, where the arrested Cabinet Ministers are confined, are not to be allowed today.

A Food Department must be set up.

Two delegates must be sent to the front to obtain information.

The Staff must more closely scrutinise the barges sailing on the Neva and on the canals.

A railway strike was anticipated. A representative of the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Railwaymen’s Union (Vikzhel) demanded a permit for a delegation to be sent to Kerensky with the object of preventing an attack by his troops on Petrograd.

Resolved: Without going into the object of the delegation’s journey, to issue a permit.

A delegate arrived from the Semyonovsky Regiment and reported that the men were indignant. They wanted to go into action, but had received no orders to that effect. They did not know what to do.

Resolved: A garrison meeting is already in progress. The delegate should go there and take part in formulating the decisions on the questions he is concerned with.

Messengers arrived from the front one after another, fatigued, drenched to the skin, and covered with mud. They reported that the men were hungry and exhausted. Colonel Walden, the commander of a detachment, sent the following message:

“Please issue immediately an order to supply bread and provisions for 1,500 men of the Tsarskoye Selo defence unit in the village of Pulkovo. The provisions must arrive not later than 12 noon, otherwise the unit will no longer be fit for action. Two motor trucks are being sent to bring the provisions. Everything depends upon their timely arrival.”[20]

The order for provisions was issued at once. The Military Revolutionary Committee sent the following urgent instruction to the Bakers’ Union:

“Send immediately a group of bakers to the Smolny Institute, so that the troops arriving to assist revolutionary Petrograd may not go without bread.”[21]

The Deputy Commissar of Supplies for the workers’ guard and the troops at the approaches to Petrograd received the following order:

“Immediately obtain from Area Stores provisions necessary to feed the workers’ guard and the troops fighting at the approaches to Petrograd in a quantity sufficient for 8,000 men for one day: tinned meat, bread or biscuits, butter, cereals, sugar and tea. Give a receipt for the provisions received. In the event of refusal, delay, equivocation, or any other excuse on the part of the Area Quartermaster . . . you are hereby instructed to call for a military unit, arrest the recalcitrants, take the necessary provisions from the stores and draw up a report on the case. Act vigorously and promptly. Report date and time of fulfilment of this order.”[22]

Meanwhile, fresh forces, arms and other war material were dispatched to the front in increasing quantities. An order was sent to the Central Committee of the Baltic Fleet in Helsingfors to prepare a torpedo boat for action and to await further orders.

Muravyev, the Commander of the Petrograd Military Area, ordered that

“all the war planes be prepared for action. Four aeroplanes must be at the aerodrome at dawn and await further orders. The remainder to be held ready in reserve. . . .”[23]

Searchlights were dispatched to the front. Telephone operators were also sent. Workers were hastily enrolled in detachments for digging trenches. The Fortress of Peter and Paul sent four armoured cars. All the hand grenades were collected from the Winter Palace. Separate detachments and regiments were dispatched to the front by rail. Reinforcements arrived from Kronstadt: sailors and Red Guards. Everything for the front! The people of the capital read the following reassuring proclamation of the commander in charge of the defence of Petrograd:

“I order all the staffs, administrations and public offices to carry on as usual. I assure the citizens of the capital that they need have no anxiety about the maintenance of order. Ruthless measures will be taken to restore order if it is disturbed by the enemies of the revolution.”[24]

Having risen to meet the enemy, working-class Petrograd, bristling with bayonets, prepared for the decisive battle. It was imbued with only one overwhelming desire: to defeat and crush the enemy at all costs.

In the evening of October 29, a conference of representatives of the Petrograd garrison was held under the auspices of the Military Revolutionary Committee. Forty representatives of military units were present. The agenda was as follows: 1. Information; 2. The formation of a staff; 3. The arming of the units; 4. The maintenance of order in the city.

At this conference Lenin spoke three times and, as always, was clear, calm and confident. Speaking amidst tense silence, he infused his auditors with fresh strength and courage.

“. . . The political situation has now reduced itself to a military one,” he said. “A victory for Kerensky is unthinkable. If that were to happen there would be neither peace, nor land, nor freedom. I am confident that the Petrograd soldiers and workers who have just accomplished a victorious insurrection will succeed in crushing the Kornilovites. . . . The political task, and the military task, is to organise a staff, to concentrate the material forces, and to supply the soldiers with all they need. This must be done without the loss of a single hour, or a single minute, so that everything may proceed as victoriously as it has done up to now.”[25]

Thus, inseverably linked with the masses of the working people, carefully heeding their wishes and firmly leading them, Lenin consolidated the victory of the Great Proletarian Revolution.

[1] “What the Putilov Workers Provided for Defending the Revolution,” Bulletin of the Bureau of the Military Commissars, No. 2, in Bulletin of the Bureau of the Military Commissars. Organ of the Bureau of the Military Commissars of the People’s Commissariat for War, Nos. 1-8, 1917-1918, Leningrad Party Publishers, 1933, p. 6.

[2] The Putilov Works in Three Revolutions, Materials on the History of the Putilov Works. The History of Factories Publishers, Moscow, 1933, p. 408.

[3] V. I. Lenin, “Advice From an Outsider,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book II, p. 98.

[4] P. Dnevnitsky, “A Biblical Crime,” Yedinstvo (Unity), No. 174, October 29, 1917.

[5] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 2, File No. 15, folio 12.

[6] Ibid., folio 11.

[7] Ibid., folio 46.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid., folio 44.

[10] Ibid., folio 12.

[11] Ibid., folio 14.

[12] Ibid., folio 14 reverse side.

[13] Ibid., folio 21.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., folio 41.

[16] Ibid., folio 20.

[17] Ibid., folio 26.

[18] Ibid., folio 20.

[19] Ibid., folio 16.

[20] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 59a, folio 153.

[21] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 21, folio 8.

[22] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 60, folio 5.

[23] Ibid., folio 2.

[24] “Order to the Petrograd Military Area,” Pravda, No. 174, October 31, 1917.

[25] V. I. Lenin, “Conference of Representatives of the Regiments of the Petrograd Garrison, November 11 (October 29), 1917,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXII, p. 31.

Previous: The Cadets' Revolt Against the Soviets in Petrograd

Next: The Suppression of the Kerensky-Krasnov Mutiny