Meanwhile, in Petrograd, energetic efforts were being made in the army barracks and in the working-class districts to mobilise the revolutionary forces. The news of the occupation of Gatchina and Tsarskoye Selo by the Cossacks had the very opposite effect of what Kerensky and Krasnov had expected.

The Military Revolutionary Committee issued the following order to the District Soviets and factory committees:

“Kerensky’s Kornilov gangs are threatening the approaches to the capital. All the necessary orders have been issued for the ruthless suppression of this counter-revolutionary attack upon the people and its gains.

“The army and the Red Guard of the revolution need the immediate assistance of the workers.

“We order the District Soviets and factory committees:

“1. To detail the largest possible number of workers to dig trenches and erect barricades and barbed-wire entanglements.

“2. Where it is necessary to stop work at the factories and mills for this purpose — to do so immediately.

“3. To collect all the available stocks of barbed and ordinary wire, as well as all tools necessary for digging trenches and erecting barricades.

“4. Every man to carry with him all the arms available.

“5. To maintain the strictest discipline and be ready to support the army and the revolution by every means.”[1]

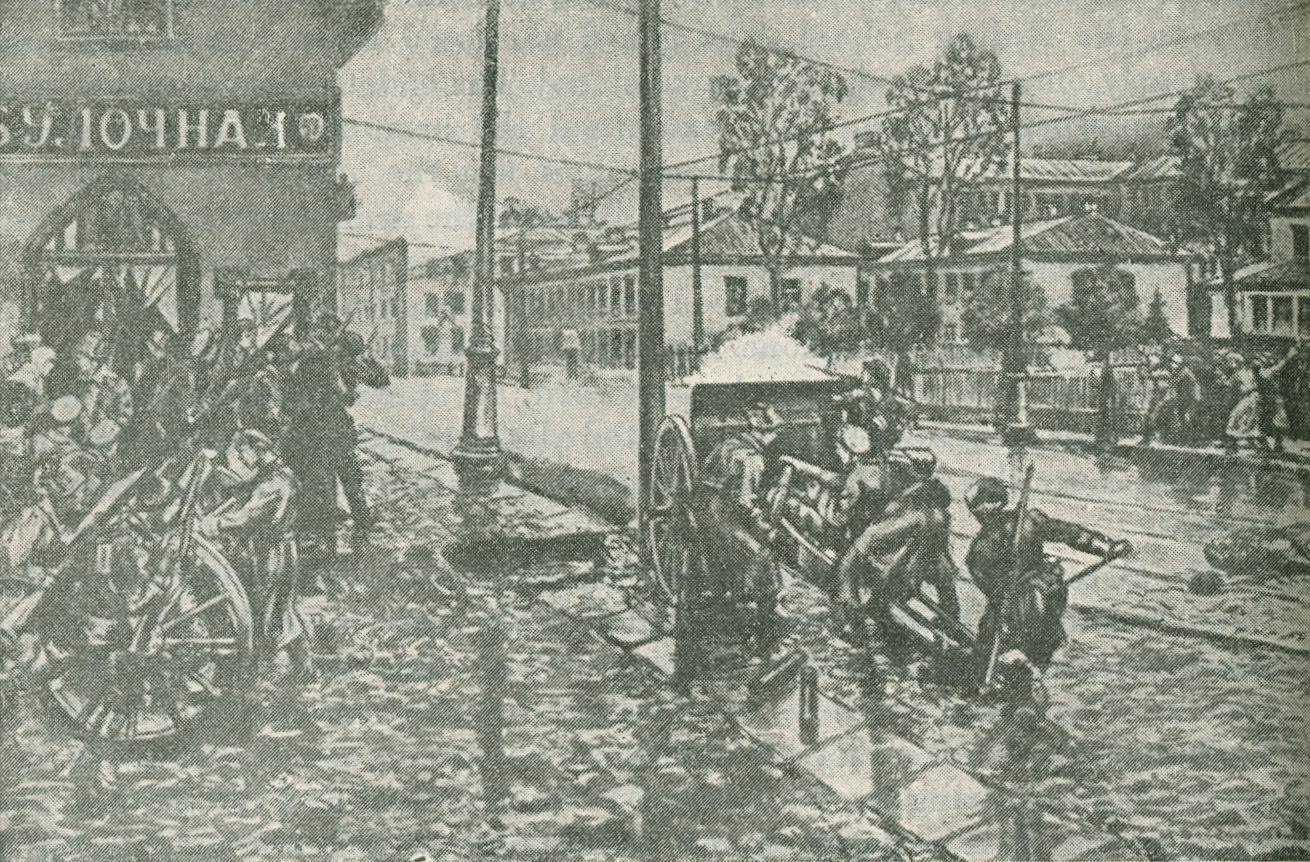

Grey, ragged clouds hung low over Petrograd, which though alarmed, was ready for battle. The shrieking of factory sirens was heard as if the different districts were calling to one another: The enemy is at the gates! Rise in defence of the revolution!

The enthusiasm among the workers was unbounded. Red Guards seized their rifles and went straight from their factories to their district headquarters where detachments were hastily formed and dispatched to Pulkovo. Many of the Red Guards were clad only in short jackets which were soon soaked with rain, but this did not dampen their ardour.

Many workers held arms in their hands for the first time and these were hurriedly put through a course of rifle practice. All night on October 28, revolutionary troops entrained for the front.

In a special manifesto the Military Revolutionary Committee warned all the citizens of Petrograd of the approach of Kerensky’s troops, but assured them that Kerensky, like General Kornilov, was leading to the capital only a few trainloads of misguided Cossacks and urged them not to allow themselves to be deceived by his false promises. The manifesto further stated:

“In obedience to the orders of the aristocratic landlords, the capitalists and profiteers, Kerensky is marching against you in order to restore the land to the landlords and to resume the destructive and detestable war.”[2]

The Military Revolutionary Committee also called upon the citizens of Petrograd to place no trust in the false declarations of the impotent bourgeois plotters.

In a later statement, the Military Revolutionary Committee informed the people about the treacherous role that was being played by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks who were actually on the side of the counter-revolution, vilifying the Soviet Government and preparing for civil war against the proletariat.

“We pillory these traitors,” said the Committee in its statement. “We hold them up to the derision of all the workers, soldiers, sailors and peasants on whom they want to fasten the former chains. They will never be able to remove from their foreheads the brand of the people’s wrath and contempt.

“Shame and disgrace upon these traitors to the people!”[3]

Bundles of manifestos, leaflets and Soviet newspapers were sent to the railway stations where every departing train had special compartments loaded with revolutionary literature for the front. Propagandists supplied with leaflets and newspapers were sent to the nearby towns and villages.

It was decided to strengthen the defences of the Fortress of Peter and Paul in case the Cossacks should break through to Petrograd. The crew of the Aurora was called to reinforce the garrison of the fortress and the cruiser herself was instructed to cover the approaches to it. Fifty seamen from the Aurora were assigned to guard the Smolny.

The Commissar of the Naval Gunnery Practice Grounds was instructed to send all the gun crews to the fortress, and field guns were ordered from the Ust-Izhora Camps and Gunnery Practice Grounds.

The Military Revolutionary Committee instructed the works committee of the Izhora Ordnance Works in Kolpino to send all available armoured cars.

All the infantry regiments in Petrograd and its environs were ordered to select and send to the Smolny eight men from each of their hand-grenade units capable of training others to handle grenades; the committee of the grenade artificers was ordered to send 20 men.

The Staff of the Red Guard was ordered to dispatch 20,000 men to the Moskovskaya Zastava by 7 a.m. on October 29 to dig trenches.

The following telegram was sent to the Commissar of Fort Ino:

“The situation in Helsingfors is well in hand. Immediately send from the fort to Petrograd 3,000 armed men with artillery to be placed at the command of the Military Revolutionary Committee.”[4]

Messengers of the Military Revolutionary Committee brought arms from the regiments stationed in Finland. Gusev, a member of the Regional Committee of the army, navy and workers of Finland, obtained from the 2nd Infantry Reserve Regiment over a thousand rifles and a large quantity of ammunition.

The Military Revolutionary Committee called upon the garrisons of the districts adjacent to Petrograd to resist the forces of Kerensky and Krasnov. The following order was issued:

“To the Commander of the Guards Reserve Cavalry Regiment, to the Novgorod Soviet of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, to the Selishchensky garrison, the garrison of the village of Medved, and others. No. 1565. October 28, 1917.

“The Military Revolutionary Committee of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies orders all the above-mentioned forces, immediately on the receipt of this order, to form battalions to be dispatched to Petrograd and to occupy Dno Station and other points, as circumstances may demand.

“All battalions must be supplied with a sufficient quantity of provisions and arms and ammunition.”[5]

This order met with response from numerous quarters, and soon reports were received from many towns of the measures which had been taken. Thus, the Commander of the 428th Lodeinopolsky Regiment reported that a column of 500 men with machine-gun and trench-mortar detachments would arrive in Petrograd on the morning of October 29.[6] Incidentally, this communication was intercepted and delivered to the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” which claimed that this battalion was loyal to the deposed government.

The Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in the towns along the route of the troops marching from the front were ordered by the Military Revolutionary Committee: 1. To take over power in the town and in the uyezd; 2. Not to obey any orders issued by Kerensky or his supporters; 3. Immediately to establish strict control over all public institutions....; 4. To prevent the transfer...of troops marching against revolutionary Petrograd.[7]

Work at the Headquarters of the Military Revolutionary Committee went on without interruption. A constant stream of workers and Red Guards came to receive instructions and departed again.

All the work was conducted under the immediate direction of Lenin and Stalin, who were almost continuously to be found in one of the committee rooms. They issued the orders calling for troops and sent members of the Central Committee to verify the execution of orders. A frequent visitor to this room was Dzerzhinsky, upon whom devolved the function of combating the sabotage organised by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. Dzerzhinsky received all the reports about the counter-revolutionary actions of the Army and Fleet Committees. To the Naval Revolutionary Committee, he sent the following order concerning the Central Executive Committee of the Navy which was controlled by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks:

“The Military Revolutionary Committee hereby orders the Revolutionary Naval Committee immediately to send to Kronstadt the members of the former Central Executive Committee of the Navy who decline to assist in the work of consolidating and saving the Russian revolution, there to be detained until the political situation in the country becomes clear.”[8]

An enormous amount of work was accomplished by Sverdlov. Possessing a remarkable memory, he remembered the countless numbers of people he had met in the course of his Party work and was always asked for his opinion of people whom it was intended to entrust with some responsible task. He carefully inquired whether all the Bolsheviks who had been imprisoned by the Provisional Government had been released. Above the noise that filled the ante-room of the Military Revolutionary Committee his stentorian voice was constantly heard giving instructions.

Lenin’s tireless activities knew no bounds. He seemed to be everywhere. He personally visited the factories and front line positions to verify the readiness of the Petrograd proletariat for battle. His cheerful smile and calm voice imbued everybody with unshakeable confidence in the justice of his cause. He weighed the temper of the masses and tested their fighting spirit.

The proletariat of Petrograd hastily mobilised its forces to resist Kerensky’s troops.

Meanwhile, the enemies of the Soviet Government feverishly prepared for armed action within the capital, which was to synchronise with General Krasnov’s advance. Representatives of the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” visited the army barracks and tried to rouse the soldiers against the Soviet Government, but not a single army unit did they succeed in persuading to defend Kerensky. They visited the Cossacks, but they too were very indefinite. The Cossack officers promised to bring their men out if at least one infantry unit supported them. A definite understanding was reached with several military schools, but even then it was only with the commanding personnel.

The energy spent in the effort to organise the mutiny was enormous, but the effective forces mustered as a result of this effort were ridiculously meagre.

Among the papers belonging to “General Staff Colonel Polkovnikov, Commander of the Troops of the Committee for the Salvation,” as he signed himself in his orders, the following note was found written on the reverse side of a poster:

“Mobilised

a. Nikolayevsky Engineers—200 bayonets (liaison Y. Weinstein) 2 companies.

b. Disabled Battalion—130 men, bayonets (Cossacks) Sub-Lieutenant Shatilov (liaison).

c. Vladimirsky School—150 men (2,000 rifles, 12 machine guns cartridges).

d. Pavlovsky School—300 men (no rifles).

e. Constantinovsky Artillery (?).

f. Mikhailovsky Artillery (?).

g. Nikolayevsky Cavalry (?).

h. Engineering Cadet School (50 men)+rifles without cartridges.

Armoured cars

Artillery

Passenger Automobiles

Motor Trucks

Food Supply

Water

Communication

Supply Corps

Ambulance Corps.”[9]

In all, a matter of 830 men, dispersed over the city, many of them without rifles. To raise a mutiny with such forces was an obvious gamble. Their only hope lay in taking the enemy by surprise, in making a sudden attack upon the Soviet troops in the rear when the forces of Krasnov and Kerensky would make a frontal attack on Petrograd and thus cause confusion in the ranks of the defenders of the proletarian revolution.

On the evening of October 28 Stankevich returned to Petrograd from his visit to Kerensky. In the offices of the “Committee for the Salvation” he found considerable animation and heard a lot of talk about connections having been established with all the units of the garrison. The “Committee” considered that it was in command of a “very considerable armed force.”[10]

The work of organising this anti-Soviet mutiny was directed by the Socialist-Revolutionaries. During the trial of the Socialist-Revolutionaries in 1922, Rakitin-Braun, the Secretary of the Military Commission of the Central Committee of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, stated the following:

“I, Krakovetsky, and Bruderer called a meeting of the Military Commission at which it was decided to commence action as soon as Kerensky’s troops approached Petrograd. Accordingly, we established closer connections with the Socialist-Revolutionary groups in all the cadet units. We were in touch with the Constantinovsky Artillery School, the Mikhailovsky Artillery School, the Pavlovsky and Vladimirsky Infantry Schools and the Nikolayevsky Engineering School. We established connection, though somewhat weak, with the Nikolayevsky Cavalry School. On November 8, 9, and 10 New Style [October 26, 27 and 28 Old Style—Ed.] representatives of these schools were on duty at our headquarters. On November 10, I had a meeting with Gotz, who informed me that the ‘Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution’ had appointed Colonel Polkovnikov as the leader of the insurrection.”[11]

Late at night on October 28, a secret meeting of the “Committee for the Salvation” was held at which the final plan for the armed insurrection was drawn up. This plan provided for the capture, first of all, of the Central Telephone Exchange and the Mikhailovsky Riding School, where the armoured cars were parked. The insurrection was to be started by the Nikolayevsky Engineering School, while the Pavlovsky and Vladimirsky Schools were with their combined forces to capture the Fortress of Peter and Paul. It was anticipated that the shock troops quartered in the Kshesinska mansion would join the rebels and help to capture the Smolny. The insurrection was timed to coincide with the approach of Krasnov’s forces, which according to Stankevich’s report were expected next day but one, i.e., on October 30.

Unforeseen circumstances, however, hastened the failure of the Socialist-Revolutionary adventure. On the night of October 29, a patrol from the Fortress of Peter and Paul detained two suspicious persons as they emerged from the Kshesinska mansion and were about to enter a waiting automobile. The suspects were taken to the commandant of the fortress for investigation. On the way the Red Guards who were escorting them saw one of them stealthily take something from his pocket and try to get rid of it. This was reported to the commandant. The man in question proved to be Bruderer, a member of the Central Committee of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party. He was found to be in possession of documents showing that the “Committee for the Salvation” had appointed special Commissars for the cadet schools. Another document found in his possession, written on the official notepaper of the “Committee for the Salvation,” was signed by Polkovnikov and Gotz, and addressed to all the military schools, Disabled Soldiers’ units and units of the Chevaliers of St. George calling upon them “to prepare for action and await further orders.”[12]

The commandant of the fortress sent these documents to the Military Revolutionary Committee which, in its turn, informed the Petrograd Committee of the Bolshevik Party of the impending danger. The Party Committee warned all the District Soviets, the army units and the factories. The documents found on these suspects made it clear which cadet schools and army units were preparing to take part in the mutiny.

Meanwhile, the other side was also active. News of the discovery of their conspiracy reached the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution.” The latter decided to begin the mutiny at once. Polkovnikov with a group of members of the “Committee” dashed off to the Nikolayevsky Engineering School, which occupied what was known as the Engineers’ Castle, and advised the cadets to sleep in their clothes and to keep their rifles beside their beds. At 2 a.m. on October 29, Polkovnikov issued the following order to the troops of the Petrograd garrison:

“By order of the ‘All-Russian Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution’ I take up the command of the forces of salvation. I hereby order:

“1. That no orders of the Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Committee be obeyed.

“2. That the Commissars of the Military Revolutionary Committees in all units of the garrison be arrested and dispatched to points to be specified later.

“3. That every unit immediately send a representative to the Nikolayevsky Engineering School (Engineers’ Castle).

“4. All persons who fail to obey this order will be regarded as enemies of the country and traitors to the cause of the revolution.”[13]

This order was dispatched to the various military schools and shortly after cadet patrols appeared in the streets and began to disarm the Red Guards. Here and there firing broke out. At 4 a.m. the cadets of the Engineering School were lined up and served with ball cartridges. A colonel, whose name has not been ascertained, addressed them on behalf of the “Committee for the Salvation” and informed them that Kerensky’s troops would arrive at 11 a.m. Meanwhile, the cadets were to maintain order in the city and for that purpose it was necessary for them to capture the Mikhailovsky Riding School and the Telephone Exchange.

Seventy cadets were detailed to capture the Riding School. Before their departure a staff captain, who said he was a member of the “Committee for the Salvation,” delivered another exhortation to the cadets explaining their task to them, and then led them into the courtyard. Here they were joined by five officers.

For several days already intense anti-Soviet activity had been conducted in the Armoured Car Unit, which was quartered in the Mikhailovsky Riding School. A number of the officers who supported the “Committee for the Salvation,” had succeeded in winning over some of the men, mainly drivers. At about 3 a.m. the Military Revolutionary Committee called for an armoured car to be sent to the Ismailovsky Regiment. The armoured car named “Fighter for the Right” was chosen, and a driver of the machine-gun squad who supported the “Committee for the Salvation” volunteered to drive it. As soon as the driver brought the car into the square, which at that hour was deserted, he stopped, and three men, a driver and two officers came up and got into the car. Instead of driving to the Ismailovsky Regiment, the driver headed for the Engineers’ Castle. On their arrival the officers and the driver informed the cadets that the Riding School was almost unguarded and could be captured without a fight.[14]

At about 5 a.m. while it was still dark, a detachment of cadets marched briskly to the Riding School. The guard consisted of only three men and being greatly outnumbered, they surrendered. The cadets rushed inside and disarmed another 15 men. They examined the armoured cars and found only five of them fit for action. Among these was the Akhtyrets, which had taken part in the defence of the Winter Palace. The armoured cars were sent to the Engineers’ Castle.

A detachment of cadets reinforced with officers and escorted by the Akhtyrets was sent to the Telephone Exchange.[15] Between 7 and 8 o’clock in the morning the unit, knowing the password, occupied the Exchange without a shot and immediately disconnected all the telephones of the Smolny.

At 8:30 a.m. the leaders of the mutiny issued the following order by telegraph:

“On October 29 the troops of the ‘Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution’ liberated all the cadet schools and Cossack barracks; the Mikhailovsky Riding School has been occupied; the armoured cars and artillery trucks have been captured; the Telephone Exchange has been occupied and forces are being concentrated for the purpose of capturing the Fortress of Peter and Paul and the Smolny Institute—the last refuges of the Bolsheviks, which are now isolated thanks to the measures taken. We urge you to remain absolutely calm and to render the Commissars and officers every assistance in carrying out the combat orders of the commander of the ‘Army for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution,’ Colonel Polkovnikov and of his second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel Krakovetsky, and to arrest all the Commissars of the so-called Military Revolutionary Committee. We order all military units which have recovered from the intoxication of the Bolshevik adventure and desire to serve the cause of the revolution and freedom to concentrate in the Nikolayevsky Engineering School. Delay will be regarded as treachery to the revolution, involving the adoption of the most resolute measures. Signed:

Avksentyev,

Chairman of the Council of the Republic

Gotz,

Chairman of the Committee for the Salvation

of the Country and the Revolution

Sinani,

Commissar of the All-Russian Committee for

the Salvation of the Country and the

Revolution attached to the Commander of the

Army of Salvation

Braun,

Member of the Central Committee of the

Socialist-Revolutionary Party.”[16]

The “Committee for the Salvation” issued a manifesto addressed to the soldiers, workers and the citizens of Petrograd calling upon them to refuse to dig trenches, to return to their barracks, not to obey the Bolsheviks but to rally around the “Committee.” It stated also that Kerensky’s troops were accompanied by V. M. Chernov, the leader of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party.

The followers of the “Committee for the Salvation” tried to foment mutiny in different parts of the city. At 9 a.m. the “Committee” received a message from the Union of the Chevaliers of St. George requesting that an armoured car be sent to escort a detachment to the Engineers’ Castle. “We have arms and grenades,” the commander of the detachment reported.[17] Lieutenant-Colonel Solodovnikov, the commandant of the city, reported that he had occupied the Hotel Astoria and had arrested all the Commissars who were living there.

“I am mobilising the entire male population. I will issue arms and call upon the people to fight the Red Guards. I am awaiting further orders,” added the commandant.[18]

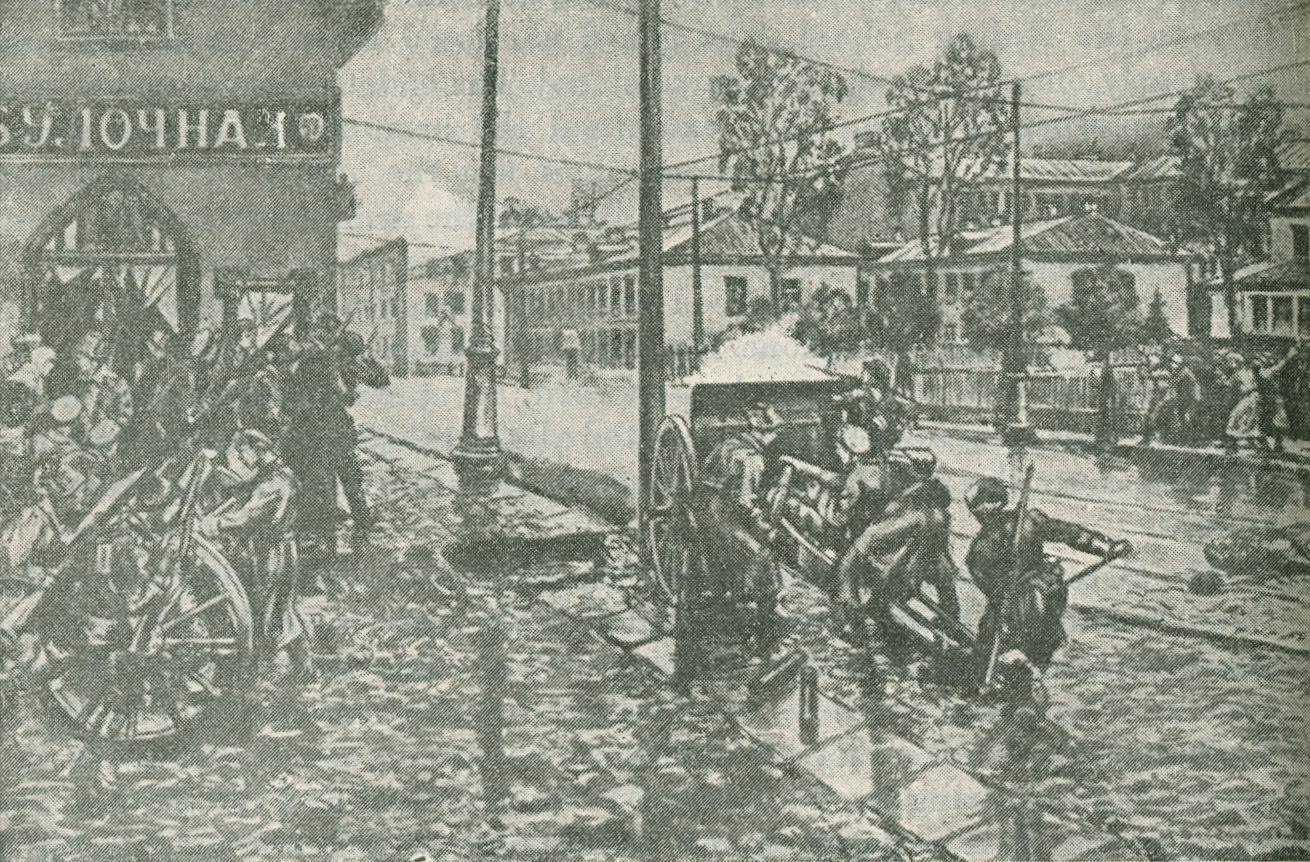

Armoured cars appeared in the main streets of the city and opened sporadic fire upon the Red Guards.

More serious events occurred at the Vladimirsky Military School. The cadets of this school had already been disarmed on October 26. Their rifles had been distributed among the soldiers serving in the school who had been appointed to guard the premises. The cadets had been given permission to go home on leave, but advantage of this had been taken only by those who lived in the city or near it.

On the eve of the mutiny representatives of the “Committee for the Salvation” had visited the school and had informed the officers and some of the cadets of the preparations being made for a mutiny. Early in the morning of October 29, when the cadets were still asleep, Colonel Kuropatkin appeared at the school with a group of soldiers from the 3rd Detachment of the Disabled Soldiers’ Battalion. The cadets were roused, and together with the newly arrived soldiers they disarmed the guard. The machine-gun detachment, which had been employed to train the cadets, opened fire; it was the only unit in the school to do so. The machine-gunners were surrounded. Some of them surrendered, but others continued to fire. This prevented the cadets from proceeding to the Pavlovsky Military School. Suddenly, firing was heard in the street, followed by the tinkle of glass from the shattered school windows. Red Guards and sailors sent by the Military Revolutionary Committee had surrounded the school and had opened fire on it.[19]

Thanks to the timely measures which had been taken, the cadet mutiny was nipped in the bud. Forewarned, the workers, sailors and soldiers who had remained in the city to maintain order rushed to the different centres of the mutiny. The cadet schools and Cossack units were immediately surrounded and isolated from each other. As Krakovetsky, the Socialist-Revolutionary and Polkovnikov’s second in command, subsequently related:

“Our Headquarters were a small island in a raging sea. We were simply overwhelmed by the armed masses.”[20]

The Vladimirsky School was closely surrounded by Red Guards, reinforced by the men of the Grenadier Reserve Regiment, the Flame-Thrower and Chemical Battalion, and the gunners of the Colt Machine-Gun Battalion in the fortress. Somewhat later, sailors from the Motor Mechanics School arrived. These had not been warned of the impending mutiny; they were roused by rifle and machine-gun fire near their school. The sailors dressed quickly, and snatching up their weapons, hastened in the direction of the shooting.

The attempt of the cadets to advance from the school and occupy the adjacent buildings was thwarted by the fire of the besiegers.

At first the siege of the school was insufficiently organised. Attracted by the firing, Red Guards came up in groups, or individually, and immediately joined in the action. Soon the armoured car Yaroslav and two guns arrived from the Fortress of Peter and Paul. Before opening fire on the school they called upon the cadets to surrender, but the latter refused. Several shells were then discharged which pierced the walls and exploded inside the building, causing panic among the cadets whose fire became very ragged.

After a few more shells were sent over the firing from the school ceased. A number of the cadets had been killed and wounded and others wanted to put out a Red Cross flag to indicate that they needed medical assistance. But no such flag could be found, so they hung out a piece of white sheeting instead. Taking this as a sign of surrender, the Red Guards and sailors advanced towards the school, but the cadets fired at them. About fifteen men fell. Enraged by the treacherous conduit of the cadets the revolutionary troops opened a hurricane fire. Some of the cadets stopped shooting. Noticing this, Colonel Kuropatkin shouted to them that Kerensky’s troops were already in the city and that the Cossacks were nearby. By this time, however, some Red Guards had forced their way into the building through the private apartment of the chief of the school. In the ensuing fighting the Colonel was killed.

The cadets then hoisted the white flag, but fearing treachery, the revolutionary troops continued to fire.

At about 4 p.m. the Vladimirsky Military School surrendered. Before surrendering, the chief of the school and his deputy removed their epaulets and tried to make their way through the lines of the besiegers, but they were detected and caught. The cadets were disarmed and their wounded taken to hospital. The rifles, cases of cartridges and machine guns were taken to the Smolny.

Somewhat earlier, the Pavlovsky Military School had surrendered. An attempt on the part of the shock troops in the Kshesinska mansion to make a sortie was observed in time and rendered abortive. Under threat of machine-gun fire from the walls of the fortress, the shock troops were called upon to surrender. This they did without offering any resistance.

The cadets’ staff remained in the Engineers’ Castle, having at its command 230 cadets, five armoured cars and about 50 shock troop volunteers. Here complete panic reigned. Everybody gave orders just as he thought fit.

Requests for aid were received, but none could be sent. A cadet from the Telephone Exchange came hurrying in to report that the Exchange was surrounded by Red units and was likely to be captured at any moment. To this Polkovnikov replied:

“The castle must be abandoned and all must disperse as best they can.”[21]

After that Polkovnikov vanished, without leaving any orders as to whether the men should surrender or retreat. The people who had been issuing orders in the name of the “Committee for the Salvation” also vanished. The cadets were abandoned to their fate by the people who had dragged them into this miserable adventure. As a result of the onslaught of the Red Guards, sailors and soldiers who were surrounding the Engineers’ Castle, and under threat of the guns mounted in the Field of Mars, the staff surrendered without a fight, not daring to go to the aid of the Vladimirsky Military School. The whole affair was restricted to a brief exchange of shots.

The cadet patrols in the streets of the city were gradually disarmed. The armoured cars which they had captured were retaken. One of these cars had been cruising round the Central Telegraph Office keeping the adjacent districts under fire. A group of sailors lay in ambush for it behind a pile of logs in St. Isaacs’ Square and as the car came up they succeeded in bursting its tyres and bringing it to a standstill. When the sailors rushed to attack it, two of them were killed, but the rest captured the armoured car and its crew.

The Central Telephone Exchange was surrounded at 11 a.m. After prolonged firing on both sides the cadets fell back from the gates and took cover in positions in the courtyard. They held out until 5:30 p.m. when they surrendered to the Red Guards.

Fearing that the cadet prisoners of war would be roughly treated by the soldiers and Red Guards who were enraged by their treachery, the Military Revolutionary Committee sent three representatives to the Telephone Exchange. On their arrival, however, they found that the cadets had already been transferred to the headquarters of the 2nd Baltic Marines.

The counter-revolutionary revolt in Petrograd was thus crushed. It had been exclusively a revolt of the cadets—the bourgeois guard which had protected the Provisional Government in the Winter Palace.

[1] “Order,” Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee and of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, No. 210, October 29, 1917.

[2] “To the Entire Population,” Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee and of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers Deputies, No. 210, October 29, 1917.

[3] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Book Repository, Leaflet Fund, Catalogue No. 9283.

[4] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 3, folio 9.

[5] Ibid., folio 11.

[6] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 341, folio 38.

[7] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 4. folio 6.

[8] Ibid., folio Iv.

[9] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 284, 1917, folio 49, reverse side.

[10] V. B. Stankevich, Memoirs 1914-1919, Berlin, 1920, p. 270.

[11] V. Vladimirova, A Year of Socialist Service to the Capitalists, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1927, p. 26.

[12] “The Military Revolutionary Committee,” Novaya Zhizn, No. 167, October 30, 1917.

[13] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 284, 1917, folio 33.

[14] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 72, 1917, folios 5, 8.

[15] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 328, Part 1, 1917, folio 13.

[16] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

[17] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 284, 1917, folio 24.

[18] Ibid., folio 26.

[19] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 139, 1917, folios 58, 59.

[20] V. Vladimirova, A Year of Socialist Service to the Capitalists, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1927, p. 29.

[21] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 328, Part I, 1917, folio 4.

Previous: The Counter-Revolutionary March on Petrograd

Next: Proletarian Petrograd in the Fight Against the Whiteguards