The information which Kerensky received from the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” about the insurrection that was being prepared in Petrograd revived his hopes for a speedy return to power.

He urged Krasnov to accelerate the opening of hostilities. Near Ostrov they met some Hundreds of the 9th Don Regiment en route to their quarters. Krasnov stopped them and ordered them to return to their train and continue their advance on Petrograd.

The news of Kerensky’s arrival in Ostrov spread through the town like wildfire. Crowds consisting mainly of soldiers from the local units began to gather outside his quarters. At first, these men in drab greatcoats stood around quietly, but soon they began to show marked signs of hostility. A commotion arose and voices were heard calling for Kerensky’s arrest. Cossacks had to be called out to protect the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. Kerensky summoned the Regimental and Divisional Committees of the Cavalry Corps and delivered an impassioned oration, but even in this assembly there were signs of hostility.

“Kornilovite!”—hissed several Cossacks in Kerensky’s face.

At this point the meeting broke up and, guarded by a platoon of Cossacks, Kerensky drove to the railway station and boarded a train. Krasnov gave the command for the train to pull out, but the engine remained motionless. Threats proved useless. Meanwhile, groups of excited soldiers began to gather outside Kerensky’s car. Krasnov then ordered the commander of his escort—who had once been an assistant engine-driver—and two Cossacks to mount the footplate. At last, about 3 in the afternoon of October 26, the train moved off. The march on Soviet Petrograd commenced.

The route lay through Pskov, where the station was crowded with armed soldiers. The train dashed through this dangerous spot without stopping. It travelled at top speed to Dno, and then on to Gatchina which was reached at daybreak on October 27.

Soon after, Krasnov received a dispatch to the effect that a mixed company of soldiers and sailors from Petrograd had arrived at the Baltic Railway Station. He sent a force of Cossacks with artillery against them. Surrounded by the Cossacks and with the muzzles of the guns trained on them, the soldiers and sailors had to surrender.

The Cossacks also succeeded in seizing the Warsaw Railway Station without a fight and in capturing prisoners and 14 machine guns.

While this was taking place, Kerensky, protected by a reliable escort and accompanied by his aides-de-camp drove off to Gatchina.

This quiet, country town was suddenly transformed into a bustling armed camp. Words of command were constantly ringing out, and the place was ablaze with the red striped Cossack uniforms.

Kerensky issued the following circular telegram:

“The town of Gatchina has been captured by troops loyal to the government and occupied without bloodshed.

“Companies of Kronstadt Marines, the Semyonovsky and Ismailovsky Regiments and detachments of sailors obediently surrendered their arms and joined the government forces.

“I order all troop trains appointed to take the road to proceed with the greatest dispatch.

“The Military Revolutionary Committee has ordered its troops to withdraw.”[1]

This sudden leap from despair, when he had occasion to fear his own generals, to transient success, turned the head of the unbalanced Supreme Commander-in-Chief. He had visions of “entire companies” surrendering their arms, although by their sudden raid the Cossacks had managed to capture only one company. Allowing his imagination to run away with him, he could see soldiers and sailors voluntarily surrendering and gleefully joining him, the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. But alas, the occupation of Gatchina did not mean that its garrison had submitted to Krasnov. In spite of all their efforts, Kerensky and Krasnov failed to induce a single unit in the town to commence active operations against the Petrograd proletariat. The most they achieved was that the ensigns of the Gatchina School agreed to perform guard duty in the town and its environs. In addition, the officers of the Gatchina Aviation School placed two aeroplanes at the disposal of the troops. That very day the aeroplanes took off and flying over Petrograd and its suburbs dropped Kerensky’s manifesto and Krasnov’s orders.

Meanwhile, the reinforcements from the front failed to appear.

On the morning of October 26, General Headquarters again got in touch with the Northern Front to make enquiries. The Chief of Staff of the Northern Front reported that it had not been possible to transmit Kerensky’s last orders about the movement of troops as the officers of the Pskov Military Revolutionary Committee on duty at the telegraph instrument had not permitted anybody to go near. Only the 3rd Cavalry Corps was on the way to Petrograd. Dukhonin requested that the following telegram be handed to Kerensky when the latter passed through Pskov:

“I believe it is necessary to move to Petrograd not only the 3rd Corps, but also the other units which have been assigned. Of course, it will be necessary to proceed in marching order, as the Railwaymen’s Union has issued an order not to transport troops to Petrograd.”[2]

General Headquarters had intended to form a mixed unit to send to Petrograd under the command of General Wrangel, but they were unable to find reliable troops.

In the afternoon of October 26, Headquarters again called up the Political Administration of the War Ministry in Petrograd. Count Tolstoi, the Deputy Chief, reported on the measures taken by the “Committee for the Salvation,” but emphasised that no forces were available in Petrograd.

General Headquarters then called up the Northern Front and learned that Kerensky had already passed through Pskov with the first troop train.

General Headquarters called up the Western Front, but the information obtained from there was far from consoling. General Baluyev reported that in Minsk power was in the hands of the Soviet of Soldiers’ and Workers’ Deputies. The Front Committee, he said, was opposed to the Soviet, but he could not answer for the garrison.

“The guard of the 37th Regiment has just been here,” added General Baluyev, “and declared myself and the entire staff under arrest and requested that we should work under their revolutionary staff. On the whole, the situation is bad, and I do not know how I shall extricate myself from it. Nor can the Commissars do anything.”[3]

Thus, General Headquarters failed to send Kerensky reinforcements on the 26th. The soldiers categorically refused to obey orders, and the railwaymen held up the troop trains that were ready to depart.

All the hoardings in the town were covered with the orders of the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee and the decrees on peace and land issued by the Soviet Government.

The ancient, gloomy palace in Gatchina, where the half-wit Paul I had resided and had delighted in his ceremonies of changing guard, was suddenly transformed. It began to hum with activity and the atmosphere of front line Staff Headquarters pervaded it. Kerensky and his adjutants took up their quarters in the rooms on the third floor. The other wing of the building was taken by the Chancellery and First Secretary of the Provisional Government. Messengers from the commandant of the town mounted the stairs to Kerensky’s apartments carrying dispatches, and officers with jingling spurs descended in a continuous stream to go off on various commissions.

Military men arrived from Petrograd with dispatches and information. Voitinsky too arrived and was immediately attached to Krasnov’s unit. He telegraphed to the office of the Commissar of the Northern Front in Pskov stating that during the present critical events he would remain constantly with this detachment.[4]

Two representatives of the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces arrived and reported on the situation in Petrograd and on the work of the Council and of General Alexeyev. They also reported that the 1st, 4th and 14th Cossack Regiments quartered in Petrograd would meet the 3rd Cavalry Corps as soon as it approached the capital. One of the representatives of the Council was ordered to remain in Gatchina, while the second returned to Petrograd to report that the Cavalry Corps was approaching the city and that the Cossacks must be ready to take action against the Bolsheviks at the proper moment.

Kerensky sent the following order to the troops of the Petrograd Military Area:

“I hereby announce that I—the Prime Minister of the Provisional Government and Supreme Commander-in-Chief of all the Armed Forces of the Russian Republic—have this day arrived at the head of the troops from the front who are loyal to our country. I order all the units in the Petrograd Military Area which, owing to ignorance or error, have joined the gang of traitors to our country and betrayers of the revolution, to resume forthwith . . . the performance of their duties.”[5]

Again and again Kerensky sent peremptory telegrams to General Headquarters and to the Staff of the Northern Front demanding that the dispatch of troops be accelerated. The Generals promised, made reassuring replies, but there was no sign of the promised troop trains. Instead of troops Kerensky received a telegram from the Staff of the Caucasian Front in which the Commander-in-Chief, General Przhevalsky, and the Commissar of the Front, Donskoy, expressed indignation at the insurrection in Petrograd and solemnly promised to support the Provisional Government.

But the Caucasian Front was thousands of miles away, so what were these promises worth? Kerensky sent a dry reply thanking them, but unable to forego the opportunity of posing once again like Khlestakov in Gogol’s Inspector-General, this Supreme Commander-in-Chief who had failed to receive a single troop train from the front concluded his message as follows:

“Glad to assure you that the entire army on active service is imbued with the same buoyant spirit.”[6]

Kerensky rushed about like a cornered rat. He wrote letters to individual commanders and officers of his acquaintance. On his instructions Captain A. Kozmin, the second in command of the Petrograd Military Area, who had fled with him from Petrograd, wrote letter after letter to various individuals appealing for assistance. Through Schreider, the Mayor of Petrograd, he wrote to Colonel Krakovetsky, a Socialist-Revolutionary in Petrograd. From an officer whom the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” had sent to Luga he had learned that this Krakovetsky was taking part in the preparations for the counter-revolutionary insurrection, so he wrote to him as follows:

“I would ask you, my dear Colonel, to communicate with me in order to settle questions connected with ridding Petrograd and its environs of the Bolsheviks. . . . Send your reply with my courier, or better still, send your delegate to me for liaison, and I will arrange with him our future joint action.”[7]

Kozmin sent a similar request to Count Rebinder, the Commander of the Reserve Guards Horse Artillery Brigade. In a letter to the Commander of the Disabled Soldiers’ Rifle Regiment informing him of Kerensky’s arrival in Gatchina, he begged for “all the assistance in your power for our common cause.”[8] Kozmin’s begging letters failed to reach their destinations, however; his couriers were intercepted by the representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee. The Military Revolutionary Committee also gained possession of Kozmin’s letter to the Political Department of the Ministry for War requesting information about Kerensky’s family and asking that one of the officials of the department be sent to Gatchina.[9]

The men in Kerensky’s entourage gave him the addresses of regiments and units commanded by men of their acquaintance. One of the officers informed him that a friend of his was in command of the 5th Armoured Car Detachment. Kerensky telegraphed to the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front ordering him to direct that detachment immediately to Gatchina-Tsarskoye Selo. Not trusting the Staff of the Northern Front, Kerensky ordered his aide-de-camp, Senior Lieutenant Kovanko, to dispatch the following telegram directly to the 5th Armoured Car Detachment:

“The Supreme Commander-in-Chief orders you to facilitate the speedy preparation and dispatch of the 5th Detachment, to be placed at the disposal of General Krasnov, Commander-in-Chief of the Army operating near Petrograd.”[10]

Giving up hope of the arrival of the troop trains from the front, Kerensky eagerly clutched at rumours about the existence of guerilla detachments and volunteer battalions who were said to be ready to come to his aid. Late that night he sent the following telegram to General Dukhonin at General Headquarters, and to the commandant of the town of Orsha:

“I order you to take immediate measures to give free passage through Orsha of all volunteer battalions proceeding in the direction of Gatchina-Tsarskoye Selo to place themselves under my command.”[11]

By midnight it was found that the only town to respond to all these appeals and requests for aid was Luga where the Chairman of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies was the Socialist-Revolutionary, Voronovich. Voronovich had been visited by representatives of the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution,” and by the Commissar of the Central Executive Committee of the Petrograd Military Area, Malevsky. The Luga Socialist-Revolutionaries promised that a part of the First Siege Artillery Regiment consisting of 800 men would be sent to Gatchina.[12]

Throughout October 27, only two and a half Hundreds of Cossacks joined the forces of Kerensky and Krasnov. A Cossack patrol, which had been sent out in the direction of Pulkovo, captured a stranded armoured car and brought it to Gatchina, where it was repaired and handed over to the detachment.

The occupation of Gatchina by the Cossacks was reported that very day to the Military Revolutionary Committee in Petrograd; and throughout the day the Commissars of the Gatchina garrison and individual soldiers and workers sent reports about the Cossacks’ activities.

At first the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee concentrated its attention on Krasnoye Selo, the direction from which the Cossacks’ advance against Petrograd was expected. A mixed detachment of revolutionary forces consisting of four armoured cars, a battalion of the Kronstadt Marines with four machine guns, a battalion of the Helsingfors Regiment with four machine guns, and a battery of six guns from the Vyborg Regiment were ordered to Krasnoye Selo.

Events showed, however, that the Cossacks intended to launch their main drive against Petrograd not through Krasnoye Selo, but via Tsarskoye Selo and Pulkovo. The Pavlovsky Reserve Regiment was therefore sent to Tsarskoye Selo, while the sailors’ detachments together with detachments of the workers’ Red Guard were concentrated along the route to Pulkovo. Later on artillery and the Petrograd and the Ismailovsky Reserve Regiments were sent there.

At the same time, the Military Revolutionary Committee took measures to protect the southern and south-eastern suburbs of Petrograd. This fortified zone was later known as the “Petrograd defence line,” or the “Gulf-Neva position,” the latter name more correctly describing the line it occupied. This defence line was divided into sectors and occupied by units of the Red Guard, the Lithuanian Reserve Regiment, and other units of the Petrograd garrison. During October 27 and 28 trenches were hastily dug here, and barbed-wire entanglements put up.

In view of the appearance over Petrograd of a Whiteguard aeroplane which dropped Kerensky’s leaflets—the second aeroplane made a forced landing near Ligovo and was captured—the Military Revolutionary Committee gave orders to prepare for action the aircraft at the commandant’s aerodrome in Petrograd.

The Military Revolutionary Committee carried out all these measures under the direct guidance of Lenin.

On October 27 Lenin and Stalin appeared at Staff Headquarters and requested a report on the plan of operations. Podvoisky enquired whether this visit signified distrust, but Lenin sharply and firmly answered:

“Not distrust. The workers’ and peasants’ government simply wants to know how its military authorities are functioning.”[13]

Lenin was not satisfied with the report, and after carefully studying the map he pointed to quite a number of omissions and careless mistakes in the military preparations. It was evident that this newly formed staff had not yet mastered its functions.

Lenin requested that another desk be brought into Podvoisky’s room, sat down and began to examine every detail of the plan. He summoned representatives of the factories, collected information about the number of guns available, and gave orders to have armour plate attached to railway cars to form an armoured train.

It was Lenin’s idea to summon the ships of the Baltic Fleet to assist in the defence of Petrograd. On October 27 he called up the representative of the Finnish Regional Committee of the army and fleet, informed him that Kerensky had captured Gatchina and demanded the immediate dispatch of reinforcements. Helsingfors enquired:

“Anything else?”

Lenin answered:

“Instead of the question ‘anything else?’ I expected you to say that you were ready to put off and fight.”

The head of the Military Department of the Regional Committee then came to the telegraph instrument and the following conversation ensued:

“How many bayonets do you need?”—asked the Chairman.

Lenin replied:

“We need the largest possible number of bayonets, but they must be in the hands of men who are loyal and ready and determined to fight. How many men like that have you?”

“As many as five thousand. We can send them out at once, men who will fight.”

“In how many hours can you guarantee that they will be in Petrograd if sent off with the utmost dispatch?”

“Twenty-four hours from now at the utmost.”

“By land?”

“By rail.”

“Can you provide food for them?”

“Yes. We have plenty of provisions. We also have 35 machine guns. We can send these with the gun crews without affecting the situation here. We also have a few field guns.”

“On behalf of the government of the republic I urgently request you to proceed to dispatch these forces immediately. Please inform me also whether you are aware that a new government has been formed and what the attitude of your Soviets is towards it?”

“So far we know about the government only from the newspapers. The transfer of power to the Soviets is welcomed here with enthusiasm.”

“And so, the land forces will start off immediately and you will ensure the supply of food?”

“Yes. We shall start sending them off immediately and supply provisions.”[14]

Lenin then called up the Chairman of the Central Committee of the Baltic Fleet and demanded the dispatch of several warships ready for action to assist the Petrograd proletariat.

Lenin not only called for reinforcements, but at once drew up a brilliant plan whereby the fleet would assist the land operations. On the arrival of the warships they were utilised in the following manner.

The cruiser Oleg and the battleship Respublika were anchored in the Morskoy Canal, where in case of necessity they were to open fire on Tsarskoye Selo and the roads leading from there to Petrograd. The torpedo boats Zabiyaka, Pobeditel and Metki were sent up the Neva to a point near the village of Ribatskoye, where they trained their four-inch guns on the north-eastern outskirts of Tsarskoye Selo and on the approaches from it to the Nikolayevsky railway line.

The officers of the torpedo-boats refused to carry out this order, whereupon the sailors themselves undertook to take the ships to their stations.

Stalin supervised the carrying out of Lenin’s orders. He received delegations from the factories and summoned and carefully instructed the district Party organisers. He performed prodigious work in preparing the garrison to resist the forces of Krasnov and Kerensky. Scores of Commissars as well as rank-and-file soldiers came to him to report on the temper of the men. Invariably he ended the conversation with each of them with the question—his pencil poised, ready to take down the answer—“How many effectives can you provide?”

The defence of Petrograd was entrusted to Lieutenant-Colonel Muravyev, an officer who began his military career in the 1st Neva Infantry Regiment and later served as an instructor at the Kazan Military School. A man with no definite political convictions, he was extremely ambitious, which drove him from one extreme to the other. At the beginning of the revolution he formed bourgeois shock units, the main function of which was to combat the revolution. During the Kornilov mutiny he swung over to the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries. During the October armed insurrection he accepted the post of Commander-in-Chief of the Petrograd Military Area although the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries had forbidden their members to hold responsible posts under the Soviet Government. Subsequently, he betrayed the Soviet Government.

Muravyev’s Commissar was Comrade Yeremeyev, a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee. He was an old Bolshevik who had been one of the editors of the Bolshevik newspapers Zvezda and Pravda in the period of reaction and revolutionary revival in 1908 to 1914. During the Great Proletarian Revolution he commanded some of the detachments which captured the Winter Palace. Muravyev’s Chief of Staff was Colonel Walden.

The arrival of Lenin and Stalin at Headquarters had immediate effect upon the entire work. The nervous bustle and inefficiency characteristic of a new body gave way to order and organisation. Every man knew his place and the particular function he was to perform. Scores of men, looking calm and resolute, left the Headquarters carrying the orders of Lenin and Stalin to different parts of the city.

Stalin proposed that first of all stock be taken of all the available arms. The Commissars of the regiments, of the arsenal and of the munition factories sent in reports of the number of rifles and machine guns in their possession. Representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee drove to the arms depots in trucks, loaded them with rifles and ammunition, and immediately sent them off to the front near Pulkovo. The Military Revolutionary Committee took over all the available automobiles and motor trucks. The garrison was put in a state of preparedness. Where there were no Commissars they were appointed. In some units the soldiers were advised to elect their own Commissars. For example, the Military Revolutionary Committee sent the following order to the Guards Reserve Artillery Battalion:

“We hereby instruct the battalion to elect a Commissar if one has not been appointed, to prepare the detachment for action, and to carry out the orders of Area Headquarters.”[15]

All the officers who had been previously employed at the Headquarters of the Petrograd Military Area, at the Ministry for War and the Admiralty were ordered immediately to resume their duties. Those failing to do so were threatened with prosecution before a revolutionary tribunal.

Propagandists were sent to the towns and villages along the railways to spread among the working people the news about the revolution in the capital.

The new government appealed directly to the working people, and its vigorous exhortations stimulated the initiative and activity of the masses. The Red Guards, on their own initiative, searched for stocks of arms, and on finding any, immediately informed the Military Revolutionary Committee. For example, the Red Guards at the railway station in Tsarskoye Selo, seeing an armoured train loaded with war supplies, surrounded it, prevented it from going to Kerensky’s assistance, and then reported the matter to the Military Revolutionary Committee. The latter sent a detachment of 50 men to guard the train.

At about 5 p.m., the Commissar of the Armoured Car Detachment reported that “the Armoured Car Division intends to send to Luga four armoured cars for very suspicious purposes,”[16] and he himself immediately got an armoured car ready to prevent this.

In some parts of the capital drunken riots broke out. The counter-revolutionaries were secretly selling spirits and also inciting groups of ignorant soldiers to raid the wine stores. The Military Revolutionary Committee sent out patrols which, with the assistance of the Commissars of the nearest units, searched suspicious premises, confiscated the liquor found there and arrested those who were guilty of selling spirits or inciting the soldiers to raid wine stores.

During the very first days of the insurrection the Military Revolutionary Committee suppressed a number of bourgeois newspapers. On October 25, Red Guards occupied the offices of Russkaya Volya, a newspaper which had been founded by the tsarist Minister, Protopopov; Birzheviye Vedomosti, an extremely reactionary newspaper; Obshcheye Dyelo, the newspaper published by Burtsev, and others. Taking advantage of the inadequate guard that had been placed at the offices of these newspapers, agents of the counter-revolution broke into the printing plants, carried away the type and in some cases managed to print leaflets. The newspapers which were not suppressed conducted a fierce counter-revolutionary campaign against the new government and published the orders of Kerensky and the bulletins of the “Committee for the Salvation.”

The Military Revolutionary Committee suppressed the reactionary newspaper Novoye Vremya and took over its premises for the purpose of publishing the Bolshevik Party newspaper Pravda. Rech, the organ of the Constitutional Democrats and Dyen, a pro-Constitutional Democratic paper, were also suppressed and their premises used for the publication of Soldatskaya Pravda and Derevenskaya Bednota. The reinforced guard placed over the premises of the suppressed newspapers was instructed to maintain close contact with the Shop Stewards Committees in order to keep close watch over the printing machines and type, and to prevent any material from being printed without the knowledge of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

From all quarters the Military Revolutionary Committee received information about every step taken by the troops of Krasnov and Kerensky. Reports were received from Commissars of the units which were retreating from Gatchina. Workers who had managed to filter through the lines of the enemy patrols came to the Committee to report their observations. Telegraph operators, too, sent in reports of the movements of enemy troops.

Krasnov continued to advance, meanwhile collecting all the information he could about the situation in Petrograd. He personally interrogated the officers, cadets and university students who came from Petrograd to join his forces. He telephoned his wife who lived in Tsarskoye Selo. He communicated with the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces in Petrograd and received information from them.

Late at night, on October 27, he convened a conference of Cossack Committees at which he made a report on the situation and proposed that an attack be launched on Tsarskoye Selo at daybreak, when it would be difficult for the enemy to determine the size of the advancing forces. The committees approved of Krasnov’s plan. At 2 a.m. on October 28, Krasnov’s Cossack Regiments left Gatchina for Tsarskoye Selo, sending out only small patrols in the direction of Krasnoye Selo.

The Cossacks approached Tsarskoye Selo at daybreak on October 28. On the southern outskirts of the town they were encountered by a battalion of infantry drawn up in fairly close order. An exchange of fire commenced, which soon developed into a hot battle. The Cossack Hundreds were supported by artillery and soon shrapnel began to burst over the heads of the Soviet troops. In danger of being outflanked, part of the infantry retreated towards the park.

In the vicinity of the army barracks and the Orlovsky Gate leading to the park, there was a crowd of soldiers of the Tsarskoye Selo garrison armed with rifles. When members of the Cossack Committee approached the soldiers and urged them to surrender, the officers of the garrison agreed and many of them tried to persuade the soldiers to follow their example.

Meanwhile, members of the local Military Revolutionary Committee and of the local Bolshevik Party organisation went from one excited group of soldiers to another to counteract the officers’ exhortations and read to the men the decrees of the Second Congress of Soviets on land and peace. The crowd split into two: part of the men surrendered their arms to the Cossacks; the majority, however, led by the Bolsheviks, began to move round the outskirts of the park in order to threaten the Cossacks’ left flank.

Savinkov, in a semi-military uniform, rode among the soldiers and tried to persuade them to surrender. Stankevich who had motored from Petrograd, also tried to address the men, but his attempt almost ended in disaster for him. The soldiers wanted to arrest him, but he managed to retire, “although hastily, nevertheless, with some show of dignity,” as he himself subsequently confessed.[17]

The temper of the majority of the garrison affected the Cossacks. Stankevich, in the same memoirs related that not far from Tsarskoye Selo he met a detachment of Cossacks whose “appearance and morale” made a “cheerless” impression upon him. This was confirmed by the Cossack officers who requested Stankevich “to talk to the Cossacks and inform them” that “not everybody in Petrograd had gone over to the Bolsheviks yet,” and to convince them that they “were not marching against the entire people.” Stankevich himself admitted that the Cossacks listened to his speech in gloomy silence.[18]

On the road from Gatchina several automobiles appeared containing, as Krasnov subsequently related, “Kerensky and his adjutants, and several smartly dressed, gushing ladies.”[19]

Kerensky had remained in the palace at Gatchina, where a state of siege had been proclaimed. Krasnov had dissolved the local Soviet of Workers’ Deputies and had ordered the arrest of the Bolsheviks. At 11 a.m. on October 28, Captain B. I. Svistunov, who had been appointed chief of the Gatchina garrison and commandant of the town, reported to Kerensky as follows:

“The Bolshevik members of the Soviet have been arrested. It will be necessary to disarm the 2nd Reserve Artillery Battalion, which has 300 rifles.”[20]

While waiting for reports from the front Kerensky kept calling up General Headquarters and the different garrisons in the vicinity. The information he obtained was far from reassuring, but he learned definitely that aid was coming from Luga. He ordered the following information to be communicated to Krasnov’s unit:

“1) At daybreak [of October 29—Ed.] the 4th Siege Regiment will arrive with four guns.

“2) The arrival of cavalry from Tosno is anticipated....

“3) Another battery of light artillery will arrive from Luga.

“4) The 3rd Finland Division and the 17th Don Regiment are on the way, and will arrive near Petrograd on the evening of the 29th.

“5) In Moscow the Bolsheviks surrendered this afternoon.”[21]

But all this was a matter of the future—“anticipated,” “will arrive,” but there was nothing tangible at present; nor was there any news from Krasnov at the front. At 3:40 p.m. Kerensky sent the following personal message to General Krasnov:

“I consider that the occupation of Tsarskoye Selo must be completed at the earliest possible date.”[22]

To this he received no reply. Irritated by Krasnov’s silence, Kerensky called for an automobile and drove to Tsarskoye Selo. As General Krasnov subsequently related, on his arrival, Kerensky asked him in an abrupt and angry tone:

“What’s the matter, General? Why have you sent me no report? I have been kept in Gatchina in complete ignorance.”[23]

Krasnov informed Kerensky of the situation. Continuing his description of this interview Krasnov goes on to say:

“Kerensky was in a high state of nervous excitement. His eyes were burning. The ladies in the automobile, whose gay appearance suggested that they were out on a picnic, were entirely out of place here, where guns had only just been firing. I requested Kerensky to return to Gatchina.

“Kerensky replied with a frown: ‘That’s your opinion, General, but not mine. I will ride up to them [the soldiers] and plead with them.”[24]

Krasnov ordered a Hundred of Yenisei Cossacks to mount and escort Kerensky.

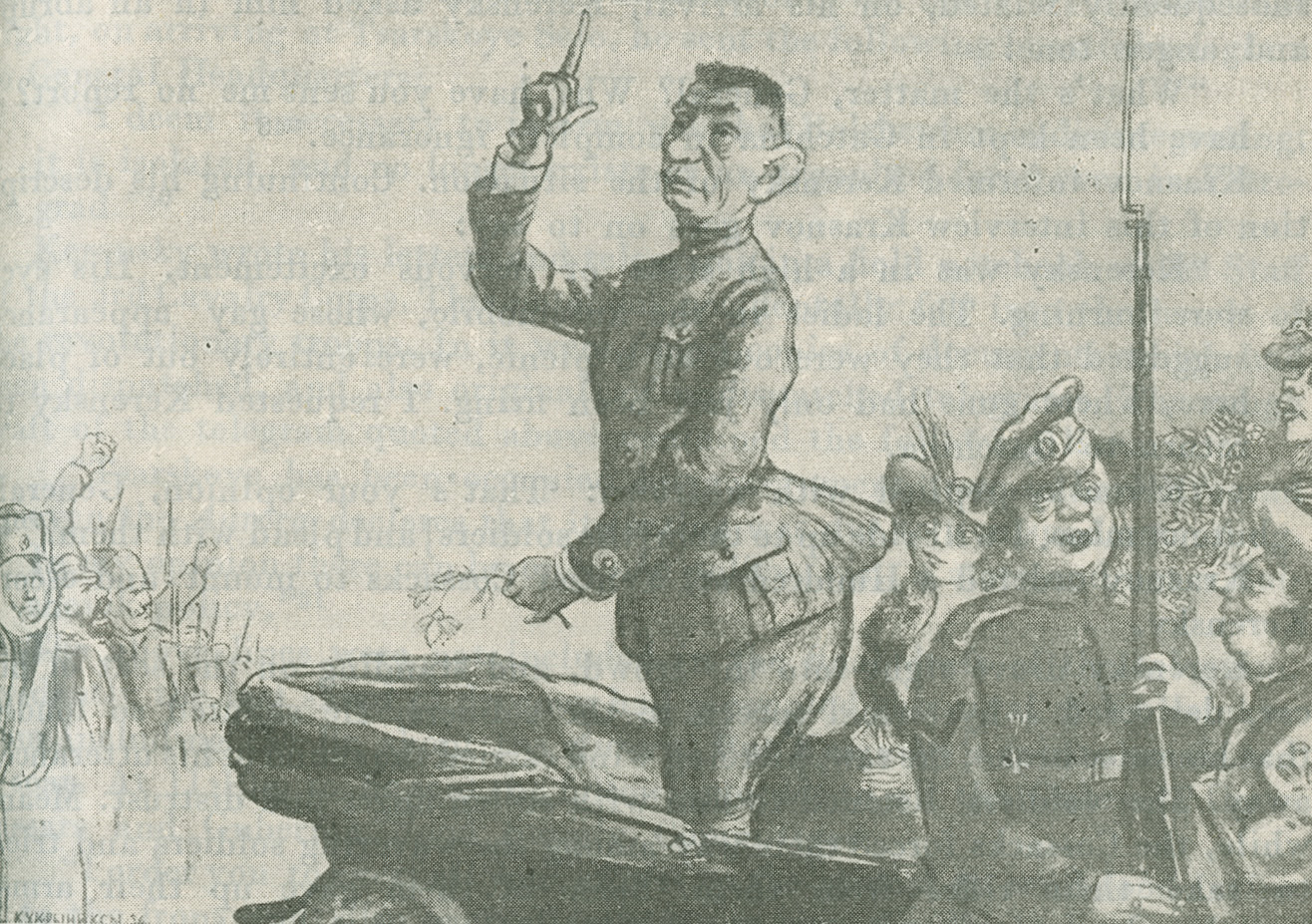

Kerensky drove right into the crowd, and standing on the seat of his car, delivered a hysterical speech to the soldiers. He shouted so loudly that his voice broke; the raw, piercing wind carried the sound of his utterances away. The soldiers listened to him with sullen anger and distrust. Meanwhile, the Cossacks forced their way among the wavering soldiers and tried to take their rifles from them. Some of them gave up their arms, but the rest, gripping their rifles firmly, rushed to the park gates where the members of the Military Revolutionary Committee were gathered. The soldiers lined up and formed detachments which quickly marched out of the park, deployed in open order and began to surround the Cossacks. A shot rang out, a second and a third, and then steady firing was resumed on both sides. Kerensky beat a hasty retreat. General Krasnov ordered his batteries to open fire. Shrapnel began to shriek and burst over the heads of the attacking soldiers.

The artillery decided the issue. With shrapnel dropping on them like hail, the soldiers scattered. The road was thus opened, and at dusk the Cossack units entered the town.

The first thing the Cossacks did on entering Tsarskoye Selo was to occupy the railway station, the Telephone Exchange and the Radio Telegraph Office. At night, they occupied the royal palaces.

Tsarskoye Selo, situated only a matter of 12 miles from Petrograd, was occupied by the counter-revolutionary troops. The farce staged by Kerensky near Petrograd threatened to develop into a tragedy for the revolution, for the Tsarskoye Selo garrison consisting of 20,000 men, could be forced to march against Petrograd. Krasnov calculated that the boom of the guns near Tsarskoye Selo would influence the Petrograd garrison and induce the waverers to join the counter-revolutionary forces.

Kerensky, who in an instant jumped from despair to elation, imagined that the capture of Tsarskoye Selo was already the herald of victory. In the afternoon of October 28 he was nervously pacing the halls of the Gatchina Palace in utter despair at the absence of news, but at 11 o’clock that night, on arriving at Tsarskoye Selo, he sent the following boastful telegram to General Headquarters:

“I deem it necessary to inform you that Bolshevism is disintegrating; it is isolated and no longer exists as an organised force even in Petrograd.”[25]

Kerensky wrote his letters and telegrams in a field notebook of the Staff of the 3rd Cavalry Corps. This notebook accidentally fell into the hands of the revolutionary troops. In it were found copies of documents which had been dispatched, and also originals of undispatched telegrams. The rough draft of the telegram quoted above contained the following lines:

“Tsarskoye has been occupied by government troops. In Petrograd even the Aurora declares that its action was due to a misunderstanding. In my opinion there can be only one policy, viz., a state and not a Bolshevik policy.”[26]

The above lines were not included in the final draft of the telegram. Evidently the last shred of decency had prevented this rival of Khlestakov from including the lie about the Aurora. But Kerensky’s spirits continued to soar. At 11:10 p.m. he sent the following order to all the Gubernia Commissars and Gubernia Food Supply Committees:

“I order you to exert all your efforts to the utmost to send food trains to the front and, also energetically, to resume the dispatch of grain to Petrograd, undisturbed by the situation which has arisen, against which the government is taking determined measures.”[27]

Kerensky was so confident that Petrograd would be captured that he even ordered grain to be sent there. He hoped to be able to enter the city bringing bread with him, and thus entirely cut the ground from under the feet of the Bolsheviks.

At 11:25 p.m. he sent a telegram addressed to all the Cabinet Ministers and chiefs of departments in as yet uncaptured Petrograd, ordering them to refuse to carry out the orders of the People’s Commissars, not to enter into any negotiations with them, and not to allow them to enter the government offices.[28] He ended that day by sending the following message to General Krasnov:

“I think that, the movement of the troop trains permitting, the position in Tsarskoye Selo should be consolidated by the morning, so that preparations may be started for the liquidation of St. Petersburg. Greetings. A. Kerensky.”[29]

Calmer, and inspired by the rosiest of hopes, Kerensky retired for the night. In the distance the sky reflected the lights of Petrograd, and it seemed to him that after his ignominious flight, he was already back in the capital as Prime Minister of the Provisional Government and Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Forces.

[1] “Kerensky’s Telegram to the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front,” Rabochaya Gazeta, No. 198, October 28, 1917.

[2] “Documents,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. VII, Berlin, 1922, pp. 310-311.

[3] Ibid., p. 315.

[4] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 543, File No. 10, 1917, folio 44.

[5] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, 1917, folio 1.

[6] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 380, File No. 26, 1917, folio 8.

[7] Ibid., folios 1 and 2.

[8] Central Archives of the October Revolution. Fund 380, File No. 26, 1917, folio 22.

[9] Ibid., folios 25 and 26.

[10] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, 1917, folio 4.

[11] Ibid., folio 2.

[12] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 158.

[13] N. Podvoisky, “During the October Days,” in Lenin During the First Months of the Soviet Regime, Party Publishers, Moscow, 1933, p. 64.

[14] V. I. Lenin, “Conversation with Helsingfors over Direct Wire, November 9 (October 27), 1917,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXII, pp. 27-28.

[15] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 4, folio 4.

[16] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 1, File No. 12, folio 5.

[17] V. B. Stankevich, Memoirs, 1914-1919, Berlin, 1920, p. 269.

[18] Ibid.

[19] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 161.

[20] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, folio 42.

[21] Ibid., folio 8.

[22] Ibid., folio 7.

[23] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 161.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, 1917, folio 10.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid., folio 12.

[28] Ibid., folio 13.

[29] Ibid., folio 15.

Previous: The Counter-Revolutionary Insurrection Against the Soviet Government

Next: The Cadets' Revolt Against the Soviets in Petrograd