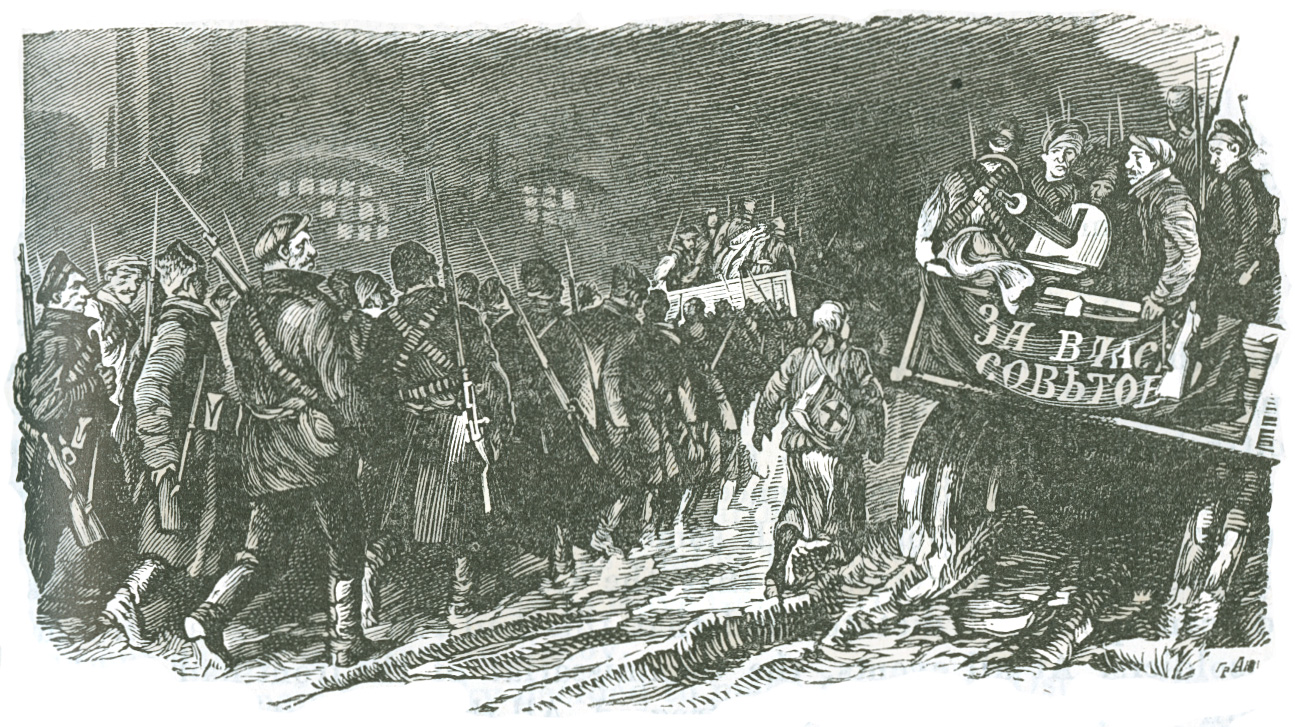

T ABOUT noon on October 25, Kerensky left the Winter Palace and dashed off in an automobile to Gatchina. There he found, however, that none of the troops which had been summoned from the front had arrived. The local garrison had already been warned of the flight of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. The soldiers gathered in groups, noisily argued among themselves, held meetings, and might have arrested Kerensky at any moment. Barely managing to refuel his car, he rushed on further in quest of the troops he had summoned, but nowhere could he find them, and the garrisons of the towns he passed through had already gone over to the Military Revolutionary Committee. Through the drizzling autumn rain and the mud, the ex-dictator’s car sped further and further into the gathering dusk.

T ABOUT noon on October 25, Kerensky left the Winter Palace and dashed off in an automobile to Gatchina. There he found, however, that none of the troops which had been summoned from the front had arrived. The local garrison had already been warned of the flight of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. The soldiers gathered in groups, noisily argued among themselves, held meetings, and might have arrested Kerensky at any moment. Barely managing to refuel his car, he rushed on further in quest of the troops he had summoned, but nowhere could he find them, and the garrisons of the towns he passed through had already gone over to the Military Revolutionary Committee. Through the drizzling autumn rain and the mud, the ex-dictator’s car sped further and further into the gathering dusk.

Late in the evening, at about 9 o’clock, Kerensky, weary and depressed, reached Pskov, the headquarters of the Northern Front. Here he learned that the Commander-in-Chief, General Cheremisov, had countermanded the order to send troops to Petrograd. Earlier in the day the Menshevik Voitinsky, the Commissar of the Northern Front, had called a conference of representatives of the Commander-in-Chief of the front, the Front Committee and of the Executive Committee of the Pskov Soviet, at which he had proposed that reliable troops should be sent to the aid of the Provisional Government in Petrograd. The conference, however, had strongly criticised Voitinsky’s proposal and had passed a vote of no confidence in him. In the evening, when the conference was resumed Voitinsky was absent. His deputy, Savitsky, reported with some embarrassment that information had been received from Petrograd that the Constitutional Democrat Kishkin had been appointed dictator and that this had roused indignation among the soldiers. At all events, the Commissariat of the front had decided to refrain from sending troops to Petrograd. All the organisations represented at the conference unanimously opposed the dispatch of troops to assist the Provisional Government. At the same time the conference decided to form a North-Western Military Revolutionary Committee and to instruct it to take all measures to prevent the dispatch of troops to Petrograd.

Later on Voitinsky appeared and reported that communications had been received from all the three armies at the front. The First Army was opposed to dispatching troops; the Fifth Army was in favour of dispatching troops, not against the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee, however, but, if anything, to assist it. Only the Twelfth Army was alleged to be in favour of sending troops. Thus, of the three armies, only one, and that only Voitinsky could vouch for, had expressed itself in favour of assisting the Provisional Government.

Declaring that he evidently did not express the sentiments of the soldiers Voitinsky offered to resign, adding that in conjunction with General Cheremisov, he had cancelled the movement of all troop trains to Petrograd.

On learning these details, Kerensky hesitated to appeal to General Cheremisov, the Commander-in-Chief of the front. Nor had he any confidence in the Pskov garrison. The Supreme Commander-in-Chief, therefore, addressed himself to Quartermaster-General Baranovsky, formerly Chef de Cabinet of the Ministry of War. The news he received there was alarming. Kerensky was informed that a Military Revolutionary Committee was already operating in Pskov, that the Telegraph Office had been placed under control, and that Staff Headquarters had received orders from Petrograd to arrest him.

Soon after, however, Kerensky summoned General Cheremisov, who confirmed the information Kerensky had received and added that he had no reliable troops at his command to send to Petrograd. General Cheremisov concluded by saying that he could not guarantee Kerensky’s safety in Pskov.

When Kerensky enquired whether Cheremisov had rescinded the order to dispatch all the troops that had been indicated, including the 3rd Cavalry Corps commanded by Krasnov, the General replied in the affirmative.

“Have you seen General Krasnov? Does he agree with you?” asked Kerensky irritably, interrupting the General.

“General Krasnov is coming from Ostrov to see me, and I expect him to arrive any minute,” answered Cheremisov.

“In that case, General, send him to me as soon as he arrives,” said Kerensky.

“I will,”[1] the General answered, and then left to attend a meeting of the Military Revolutionary Committee whither he had been summoned.

Cheremisov returned to Kerensky’s apartment at one o’clock in the morning, only to inform him that he was unable to render the government any assistance. He advised Kerensky to leave General Headquarters as he was in imminent danger of arrest in Pskov.

In utter despair Kerensky decided to make his way to Ostrov, the headquarters of the 3rd Cavalry Corps, and from there march with the Cossacks against Red Petrograd. But just before daybreak on October 26, General Krasnov, the Corps Commander, accompanied by his Chief of Staff, suddenly turned up at Kerensky’s quarters. . . .

Krasnov had not credited the order countermanding the dispatch of his Corps and had come to Pskov to verify matters. At that moment General Cheremisov, the Commander-in-Chief of the front, was in conference with the representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee whither Krasnov went to see him. Fearing that he would rouse the suspicion of the members of the Committee with whom he was conferring, Cheremisov reluctantly left the room to speak to Krasnov. In a brief conversation he advised him to return to Ostrov. Krasnov demanded an order in writing. Cheremisov, very displeased, again urged Krasnov to return to Ostrov and then returned to the conference room.

After waiting at General Headquarters for a little while the perplexed Krasnov went to see Voitinsky, whose acquaintance he had made during the Kornilov plot. He was obliged to wait a long time before he could see him, however, for the Commissar was away, at the same conference at which Cheremisov was engaged. When Voitinsky arrived he informed Krasnov in strict confidence that Kerensky was in Pskov and requested Krasnov to go and see him immediately.

Taking great precautions, Krasnov, just before dawn, arrived at the secret quarters of the fugitive Supreme Commander-in-Chief. Kerensky was overjoyed at seeing Krasnov and at once decided to accompany him to the Headquarters of the 3rd Cavalry Corps.

The 3rd Cavalry Cossack Corps had not been disbanded after the Kornilov plot. On the contrary, at the beginning of September Kerensky had ordered it to be concentrated in the district of Pavlovsk-Gatchina-Peterhof “in view of the likelihood of a German landing in Finland,” as was stated in the confidential order.[2] The very disposition of the corps showed that it was not intended to be used to combat a German landing, but to fight the Bolsheviks. Later on Krasnov gave the following reason why the Corps had been transferred:

“I briefly and quite frankly explained the situation to the officers and Cossacks. I did not conceal from them that the reason for going to Petrograd was not so much the danger of a German landing as the frightful, insidious activities of the Bolsheviks who were out to seize power.”[3]

The Corps was carefully shielded from all revolutionary influence. Krasnov had proposed that all the unreliable units should be weeded out and replaced by fresh Cossack regiments. Cavalry, however, were needed at the front to suppress mutiny among the soldiers. Moreover, the Petrograd Soviet was closely watching the suspicious concentration of Cossacks near the capital. The Corps was transferred to Ostrov, where it arrived on September 28. During the month it was stationed there, its strength waned, as several Cossack Hundreds were sent to different towns. Two Hundreds of the 10th Don Regiment with two guns were in Toropets; three Hundreds of the Ussuriisky Regiment with two guns were in Ostashkov, and five squadrons with two guns were in Vitebsk.

Round about October 20 the 51st Infantry Division, which was on the Northern Front, refused to relieve the 184th Division. The soldiers of the latter division thereupon decided to leave the trenches. All the efforts of the Army and Corps Committees to persuade them to remain were without avail. The Commander-in-Chief and the Commissar of the Northern Front issued an order to “disband the 51st Division, even if it is necessary to resort to armed force for the purpose.”[4] The task of carrying out the order was entrusted to General Krasnov’s 3rd Cavalry Corps which on October 23, was ordered by Krasnov to join the First Army in the area where the 51st Division was disposed.

On October 24, Krasnov telegraphed to the Headquarters of the various fronts and to the Staff of the First Army informing them that his troops had begun to entrain, and that the twenty troop trains would arrive at their destination within three days. He requested that the units quartered in Ostashkov, Toropets and Vitebsk be returned forthwith.[5]

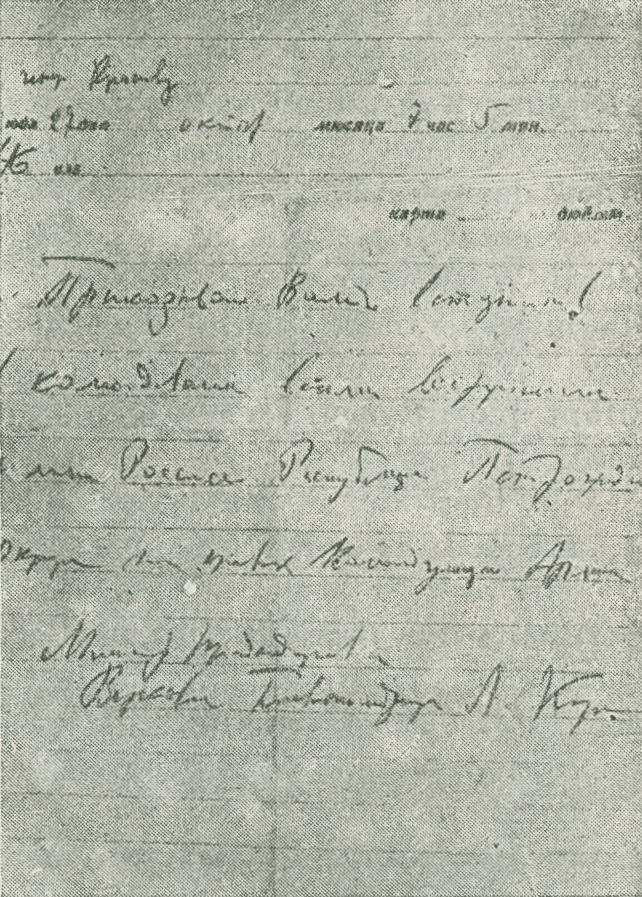

But at dawn on October 25, before the troop trains had started out, Cavalry Corps Headquarters received the following telegram, signed by Kerensky and the Acting Chairman of the Union of Cossack Forces, A. Grekov:

“I order you on the receipt of this to dispatch by rail to Petrograd, Nikolayevsky Station, all the regiments of the 1st Don Cossack Division, with all their artillery, now on the Northern Front under the general command of the chief of the 1st Don Cossack Division, to be placed at the disposal of Colonel Polkovnikov, Commander-in-Chief of the Petrograd Military Area. Wire me by code time of departure. If it is found impossible to dispatch by rail, dispatch units in echelons, in marching order.”[6]

After Kerensky’s telegram came the following manifesto, signed by the Menshevik Voitinsky, Commissar of the Northern Front:

“Convey the following to the men of the Don and Maritime Regiments:

“‘The Provisional Government, with the full consent of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, is drawing to Petrograd troops who are loyal to the revolution and to their duty to the country. The Petrograd regiments who have stubbornly refused to go to the front on the pretext of defending freedom in the rear have proved incapable of protecting Petrograd from disorder and anarchy. The convocation of the Constituent Assembly is menaced. Among the troops who are being called in this grave hour to save Russia, a leading place is occupied by the Cossack regiments.

“Let the deserters who have entrenched themselves in the rear fume against the Cossacks; the Cossacks will perform their duty to their country to the very last.”[7]

This petty-bourgeois politician, scared to death by the Great Proletarian Revolution, began to talk in the language of the tsarist generals.

At 11 a.m. on October 25, Krasnov, with manifest pleasure, gave orders to publish the appeal of the Menshevik Voitinsky.

At 7 p.m., Krasnov issued another order to the Corps. The grounds which Voitinsky had advanced for sending the Cossacks against revolutionary Petrograd had seemed inadequate to him, so he advanced his own. In his order this future henchman of Kaiser Wilhelm (in 1918 Krasnov was the head of the counter-revolutionary government set up in the Don Region) declared that the revolution had been the work of “a handful of irresponsible persons who have been bribed by Emperor Wilhelm.” He rescinded his order of October 23 and sent only one division to the First Army. To all the other units he issued the following order in pursuance of that sent by Kerensky:

“The 9th Don Cossack Regiment—5 Hundreds, 4 machine guns.

” 10th ” ” ” —5 ” 4 ” ”

” 13th ” ” ” —5 ” 4 ” ”

” 15th ” ” ” —5 ” 4 ” ”

“The 1st Don Artillery Battalion—10 guns.

“The 1st Amur Cossack Battalion—4 guns.

“Total: 20 Hundreds, 16 machine guns, 14 guns.

“Immediately to entrain at Ostrov, Reval, Pallifer and Toropets, travel via Narva and Pskov to Alexandrovskaya and there wait for the concentration of the entire division in the region of Pulkovo-Tsarskoye Selo. If these points cannot be reached by rail, fight your way through to them in entire regiments from the rail-head.”[8]

In the same order General Krasnov announced that the 44th Infantry Division, the Cycle Battalions, the 5th Caucasian Cossack Division, the 23rd and 43rd Don Cossack Regiments and a number of other units had been called to Petrograd. Such was the situation in the Cavalry Corps on the night of October 25, when Northern Front Headquarters was compelled to rescind the order for the dispatch of troops to Petrograd.

As soon as Kerensky set eyes on General Krasnov he fired a series of questions at him:

“General, where is your Corps? Is it on the way? Is it already near here? I expected to meet it near Luga.”[9]

Krasnov replied that the Corps was ready to march against the Bolsheviks, but it required infantry support. It was dangerous, he said, to move cavalry alone, and in small units at that. Kerensky ordered Baranovsky to muster all the Hundreds of the Corps which were scattered along the front and attach to the Corps the 37th Infantry Division, the 1st Cavalry Division and the entire 17th Army Corps. He asked Krasnov whether these forces would be adequate. The latter replied:

“Yes, if we muster all the forces, and if the infantry accompanies us, Petrograd will be occupied and freed from the Bolsheviks.”[10]

Baranovsky conveyed Kerensky’s order to General Headquarters. Kerensky and Krasnov rushed off to Ostrov.

General Headquarters maintained communication with Petrograd even after the surrender of the Winter Palace. After 1 a.m. on October 25, it got in touch on the direct wire with Sub-Lieutenant Scherr, the representative of the Political Administration of the Ministry of War. The latter reported the capture of the Winter Palace, after which the following dialogue ensued:

“Where are the members of the Provisional Government now?”

“They were arrested in the Winter Palace an hour ago. I have no knowledge of their present whereabouts. Minister Prokopovich was arrested earlier in the day, but later was released. . . .”

“Who is the Supreme Commander-in-Chief now?”

“Alexander Fedorovich Kerensky.”

“Where is he?”

“Vyrubov has just informed me that he is in Pskov. We know that he went out to meet the troops which were coming from the front. . . .”

“How has the Ministry of War reacted to the overthrow of the Provisional Government, the suppression of the Council of the Republic and the capture of power by the Bolsheviks?”

“By chance, the premises of the Ministry for War are not yet occupied by the mutinous troops and evidently this line is the only one in Petrograd that is not yet in their hands. The only people here are the officers of the Political Administration who have decided to refuse to do any work in the event of power being captured here, in the Administration. The premises of the Chief Administration of the General Staff and the Chief Headquarters were already occupied by the rebels in the daytime.”[11]

General Headquarters had barely finished speaking with Petrograd when they were called up by the Western Front. General Baluyev reported that he had received several orders from the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee and asked for instructions. General Headquarters enquired whether military forces were available on the Western Front which were ready to support the Provisional Government.

“I cannot answer for a single unit,” replied Baluyev. “The majority of the units will certainly not support it. Even the units that are with me may be used only for the purpose of putting a stop to rioting and disorder; they are scarcely fit to be used as a support for the Provisional Government.”[12]

General Headquarters called up the Rumanian Front and made the same enquiry about the loyalty of the troops. From there the reply came that the Executive Committee of the Rumanian Front, the Black Sea Fleet and the Odessa Military Area had decided to organise a division of picked troops, the men of which were to be recommended by the Army Committees and sent to Petrograd under the slogan: Defend the Constituent Assembly! General Headquarters interrupted the reporter impatiently and stated that they were not discussing the Constituent Assembly—that would be promised by the new government too—but whether the Rumanian Front could allocate forces for the purpose of rescuing the former government. Upon this Tiesenhausen, the Commissar of the Rumanian Front, took up the conversation.

“I am profoundly convinced,” he said, “that it is scarcely possible to move troops from the front even for the purpose of protecting the members of the government. . . . The entire front, however, would rise in defence of the Constituent Assembly and to counteract attempts to prevent it from being convened. . . . The idea of defending the Constituent Assembly is extremely popular. The composition of the former government is not particularly popular among the troops and, as such, interests the soldiers very little.”[13]

Thus, in the very first days of the civil war, the counter-revolutionaries realised that an open attack on behalf of the old regime was doomed to utter failure. Such an attack might be camouflaged with some “democratic” slogan in which the masses still had faith. Thus the Constituent Assembly was used as the slogan for mobilising the counter-revolutionary forces. General Headquarters did not realise this at once, but the petty-bourgeois traitors did so very quickly, and advanced the very slogan which they had rejected only a few days previously as a Bolshevik slogan.

General Dieterichs, at General Headquarters, called up the Staff of the South-Western Front and conveyed the same information and made the same enquiries as in the case of the other fronts. The Staff kept Dieterichs on the wire for two hours. Evidently it was collecting information. At last, to the blunt question as to whether any reliable troops were available, the Staff replied:

“Since the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front has countermanded the order to send troops, why send troops from here?”[14]

The only information General Headquarters gleaned after a long conversation was that the Cossack Committee of the South-Western Front had received instructions from the Cossack Congress, then proceeding at the front, to reinforce the guard at Staff Headquarters and to have men on constant duty at the telegraph instruments.

On the morning of October 26, General Headquarters circulated to these fronts the following telegram, which Kerensky had addressed to the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front:

“I order you on the receipt of this to continue to transfer the 3rd Cavalry Corps to Petrograd. October 26, 5:30.”[15]

This was all General Headquarters succeeded in doing during the whole night.

That same morning, October 26, Voitinsky, the Commissar of the Northern Front, appeared at the meeting of the Military Revolutionary Committee in Pskov, but in an entirely different mood. He reported that Kerensky had issued orders to move troops from the front, and that the necessary instructions had already been issued. In reply to the blunt question as to whether he recognised the authority of the North-Western Military Revolutionary Committee, he said:

“I shall obey only the Central Executive Committee, which is calling for troops.”[16]

Soon after, this Menshevik joined the forces of Krasnov and Kerensky.

While Kerensky was rushing from place to place in an effort to get at least some units moved from the front, his supporters in Petrograd were mustering their forces to strike at the revolution from the rear.

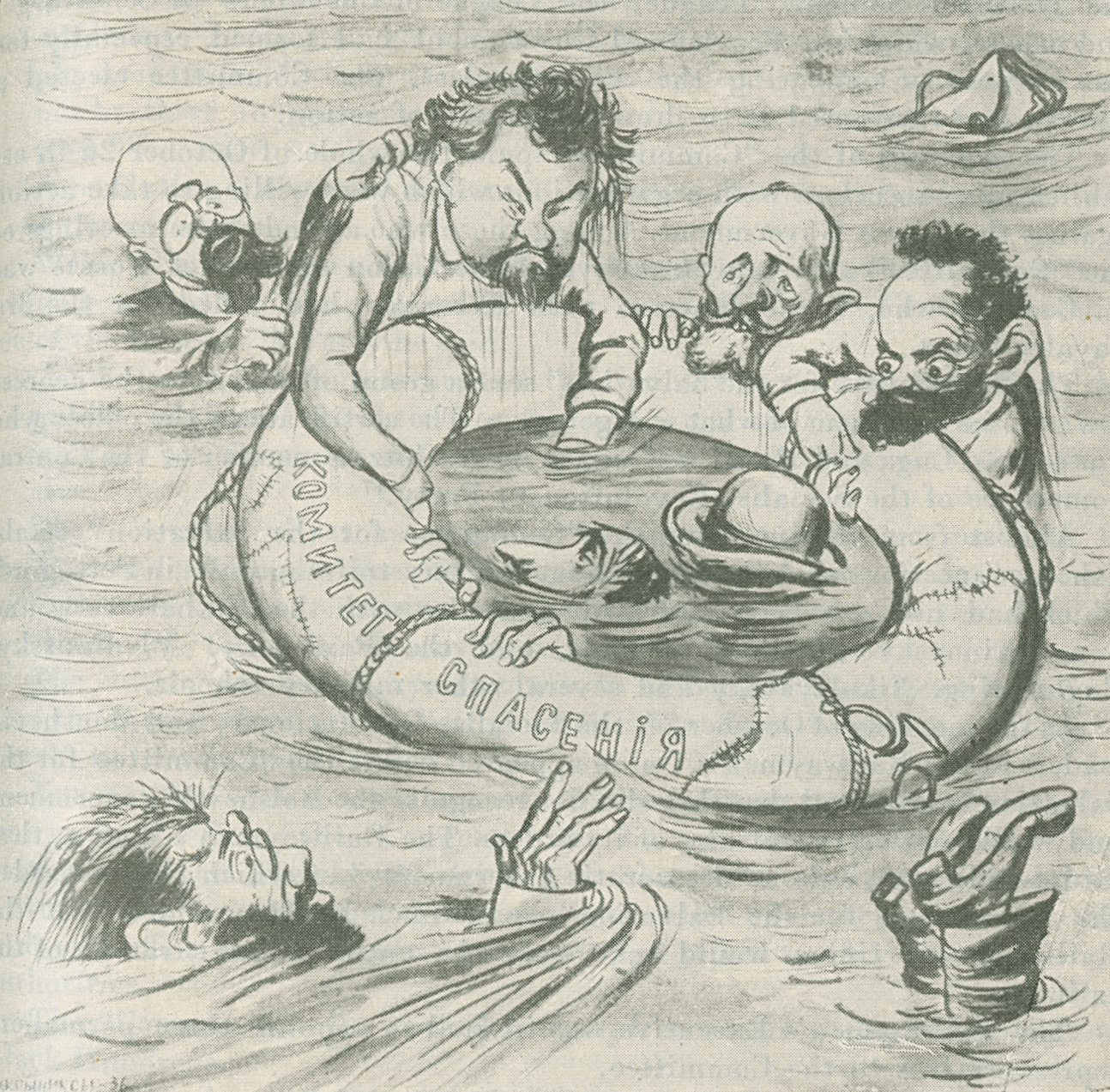

On the night of October 25, the members of the hapless procession to the Winter Palace returned to the City Duma and immediately opened a meeting of the “Committee of Public Safety.” The ex-“Socialist” Minister, Skobelev, suggested that the “Committee” should be developed into a more powerful organisation and should assume a militant character. His idea was that the new organisation should unite all the democratic forces in the country and wage a determined struggle against the Bolsheviks. This suggestion was adopted. The new organisation was given the high-sounding title of “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution.” Very soon, the Petrograd workers gave it the much more appropriate title of “Committee for the Salvation of the Counter-Revolution.”

This was the first fighting organisation of the counter-revolutionary forces to take action against the October Revolution. It consisted of the City Duma, the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik groups at the Second Congress of Soviets which had demonstratively left the Congress, members of the Pre-parliament, representatives of the Central Committees of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik parties, Plekhanov’s “Unity” group, and representatives of other anti-Soviet groups. It also included representatives of organisations such as the Bank Clerks’ Union, the Disabled Soldiers’ League, the League of Chevaliers of St. George, and others, which the Provisional Government had formed especially for the purpose of combating the working class. The Committee elected a Bureau and instructed it to draw up a plan of action.

The members of the “Committee” spent the whole of October 26 in establishing connections with organisations which were willing to take action against the Soviet Government. Among those who attended the meetings of the “Committee” as a representative of the Union of Cossack Forces was A. Grekov, who, in conjunction with Kerensky, had called for the 3rd Cavalry Corps.

The “Committee for the Salvation” sent a group of officers to the nearest towns to inform them of what was going on. The certificate of the officer who was sent to Luga and Reval was signed by A. Gotz, a member of the Central Committee of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party.[17]

Almost from its inception the “Committee for the Salvation” established connections with the anti-Soviet military training units in Petrograd, which had not yet been disarmed, and also with the Mikhailovsky and Constantinovsky Artillery Schools, and the Pavlovsky, Vladimirsky, Engineering, Nikolayevsky and several other military schools.

In the morning of October 27, the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik leaders of the Railwaymen’s Union appeared before the “Committee for the Salvation” and stated that they did not recognise the Bolshevik government and would not carry out any of its orders. The Railwaymen’s Union, they said, would obey only a “democratic government,” of which they regarded the “Committee for the Salvation” as the nucleus. They added that the Railwaymen’s Union would take over the entire administration of the railways.

The Railwaymen’s Executive was invited to appoint three permanent representatives to the Committee.

At 2 p.m., that day, in the premises of the City Duma, a meeting was held of the first Central Executive Committee of Soviets, the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies, members of the Council of the Republic, members of the City Duma, the Central Committees of the compromising parties, and other organisations. The Menshevik, M. I. Skobelev addressed the meeting on behalf of the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution.” After reporting on the formation of the “Committee” he went on to say:

“The task of the day is not only to render irresponsible demagogues harmless, but to combat the counter-revolution. Thanks to the affiliation of the Railwaymen’s Union to the Committee, not a single telegram of the new government has been allowed to pass.”[18]

This was a downright falsehood; the Soviet Government’s telegrams were being sent over the wires to all parts of the country, but this counter-revolutionary assembly loudly applauded the Menshevik’s statement; it imagined that he was talking about a force which, in fact, it did not possess.

“But this is not enough,” continued the Menshevik, encouraged by the applause. “In the struggle which lies ahead of us, we shall have to rely on physical force. We must restore the alliance between the railwaymen and our brothers in uniform. This will guarantee the salvation of the revolution.”[19]

A resolution was moved to form “Committees for the Salvation, etc.” all over the country.

Weinstein, the representative of the Mensheviks, delivered a speech in which he called for calmness and fortitude. On behalf of the Central Committee of the Menshevik Party he said:

“We must concentrate around the Committee for the Salvation the public opinion of the entire country and later, after we have ascertained whether our forces are adequate, pass from the defensive to the offensive.”[20]

The “Committee” set up a military organisation of its own members to direct armed action. At the same time, through its delegates, it got in touch with Kerensky, thus ensuring complete co-ordination with the counter-revolutionary forces which were moving towards Petrograd.

The counter-revolutionary coup was to be headed by Colonel Polkovnikov, the former chief of the Petrograd Military Area. A staff was set up to direct military operations.

Not satisfied with mustering armed forces to crush the victorious revolution under the flag of the “Committee for the Salvation,” the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks devised another form of fighting the Soviet Government, viz., sabotage. The Committee called upon the government officials and office staffs to declare a boycott and refuse to obey the Bolshevik authorities.

The “Committee” also worked in complete unison with the out-and-out Black Hundreds.

On the evening of October 26, Captain A. P. Anikeyev of the Don Cossack Forces, the new Chairman of the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces, assumed his new post at the offices of the Council. The outgoing Chairman, A. I. Dutov, had been elected an Ataman by the Orenburg Cossack Military Area and had left to take up his post. Anikeyev was accompanied by A. P. Mikheyev, the Vice-Chairman of the Council. Both reported that they had just come from a secret meeting which had been convened by General Alexeyev, the ex-Chief of Staff of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, and one of the most prominent of the tsarist generals. The meeting was still in progress, they stated, and Anikeyev requested the Council to send representatives to it at once. When the representatives of the Council arrived at the address which had been given them, they found there, in addition to General Alexeyev, B. Savinkov, the leader of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, and a cadet. General Alexeyev stated that according to his information General Krasnov’s 3rd Cavalry Corps was being moved against Petrograd, and that he and Savinkov had intended to go out to meet it. General Alexeyev was advised by those present not to go as he might be recognised and arrested. Less known people should be sent, they said. They appointed a representative of the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces and the cadet. General Alexeyev handed them the railway tickets that he had purchased earlier in the day for himself and Savinkov. The Council of the Union of Cossack Forces provided them with forged documents, and both went off to meet Krasnov’s Cossacks.[21]

The “Committee for the Salvation” made contact with the monarchist organisation headed by V. Purishkevich. This notorious chief of the Black Hundreds had formed this organisation earlier in the month, before power had passed to the Soviets. As one of its prominent members stated, its object was

“to set up a strong government for the purpose of bringing the war to a victorious conclusion and of subsequently restoring the monarchy in Russia without fail.”[22]

The organisation recruited its members from among the army officers and cadets. These were organised in secret groups of five, and no group had any knowledge of the other groups.

Purishkevich himself informed one of those whom he had enlisted that he had at his command about 2,000 devoted men in Petrograd, about 7,000 at the front, and a large number in Moscow and other towns.[23] The organisation was to operate in secret, and for the time being there was to be no talk about restoring the monarchy. Purishkevich proposed that these forces should be united with the groups which were striving for a dictatorship, such as the monarchists, the Constitutional Democrats and Savinkov’s organisation. Purishkevich’s accomplice stated:

“Purishkevich insisted particularly on establishing close connection with Savinkov and his political friends and supporters on the grounds that the monarchists were too weak to achieve success by themselves, and that without the Right ‘Socialist-Revolutionaries’ and Savinkov’s followers they were doomed to defeat.”[24]

The Great Proletarian Revolution upset Purishkevich’s plans. His organisation fell to pieces. Some of those who had been enlisted dispersed to different towns.

Purishkevich wanted immediate armed action in Petrograd itself. He strongly insisted that as the Soviet Government had not yet consolidated itself and Kerensky and the Socialist-Revolutionaries had not yet entirely surrendered power, this was the most favourable moment for taking action with the object of seizing power and restoring the monarchy. He told his fellow conspirators that he had been promised the assistance of Colonel Polkovnikov and the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution.”

Thus came into being the united anti-Soviet front created mainly by the efforts of the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries and comprising all the counter-revolutionary elements, from out-and-out Black Hundreds to the “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” led by representatives of alleged revolutionary democracy.

In their struggle against the Soviet Government, the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries also sought the aid of the imperialists of the Entente. Sir George Buchanan, the British Ambassador in Russia, relates the following in his Memoirs of a Diplomat:

“Avksentyev, the President of the Provisional Council, who came to see me today, assured me that, though the Bolsheviks had succeeded in overthrowing the government owing to the latter’s criminal want of foresight, they would not hold out many days. At last night’s meeting of the Congress of All-Russian Soviets they had found themselves completely isolated, as all the other Socialist groups had denounced their methods and had refused to take any further part in the proceedings. The Council of Peasants had also pronounced against them. The Municipal Council, he went on to say, was forming a ‘Committee of Public Safety’ composed of representatives of the Provisional Council, the Central Committee of the Soviet, the Peasants’ Council and the Committee of Delegates from the front; while the troops, which were expected from Pskov, would probably arrive in a couple of days.

“I told him that I did not share his confidence.”[25]

It is difficult to believe that Avksentyev visited the British Ambassador solely for the purpose of “exchanging news.”

[1] A. F. Kerensky, From Afar, Compendium of Articles 1920-21, Paris, 1922, p. 206.

[2] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 131.

[3] Ibid., p. 136.

[4] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Staff of the First Army, File Nos. 378-215, folios 1-2.

[5] Ibid., folio 3.

[6] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 380, File No. 26, 1917, folio 18.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Staff of the First Army, File Nos. 379-245, folio 5.

[9] P. N. Krasnov, “On the Home Front,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. I, Second Edition, Berlin, 1922, p. 150.

[10] Ibid., p. 151.

[11] “Documents,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. VII, Berlin, 1922, pp. 304-305.

[12] Ibid., p. 306.

[13] Ibid., p. 307.

[14] Ibid., p. 308.

[15] Ibid., p. 309.

[16] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 543, File No. 10, 1917, folio 45.

[17] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 286, 1917, folio 6.

[18] “The Organisation of the ‘Committee for the Salvation’” Rabochaya Gazeta, No. 198, October 28, 1917.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] A. N. Grekov, “The Union of Cossack Forces in Petrograd,” Donskaya Letopis (Annals of the Don), 1923, No. 2, pp. 272-277.

[22] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 336, File No. 328, Part I, 1917, folio 82, reverse side.

[23] Ibid., folio 21.

[24] Ibid., folio 82, reverse side.

[25] Sir George Buchanan, My Mission to Russia and Other Diplomatic Memories, Boston, Little, Brown & Company, 1923, Vol. II, pp. 208-209.

Previous: The Decrees of the Great Proletarian Revolution

Next: The Counter-Revolutionary March on Petrograd