By the beginning of October 1917 the situation had again undergone a change. The revolution had taken another step forward and had brought the country to the eve of insurrection.

In Finland power was practically in the hands of the Soviets. Yielding to the pressure of the revolutionary sailors, soldiers and workers, the Regional Committee of Soviets, on which the Defencists were still strong, was compelled to convene a Regional Congress of Soviets.

This Congress, known as the Third Regional Congress, opened in Helsingfors on September 9. It became evident at the very outset that the majority of the delegates favoured a revolutionary policy. The first two Congresses of Soviets in Finland had been dominated by Defencists; at this Congress, however, the latter were scarcely represented. The hall was filled with sailors, soldiers and workers whose very demeanour expressed boldness, determination and readiness to fight. At the very outset a stable majority was formed consisting of Bolsheviks and of “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries who had broken away from their party. These “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries consistently voted for the Bolshevik resolutions, except that on the question of power when they moved their own resolution. But on this question too the Bolshevik resolution was adopted by 74 votes against 16. The newly elected Regional Committee of Soviets consisted of 37 Bolsheviks, 26 “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and two Menshevik Internationalists.

After the Congress the local Soviets in Finland rapidly became Bolshevised. In the larger towns, such as Vyborg and Helsingfors, the Bolsheviks predominated in the Soviets. At the same time the Soviets in other towns in the vicinity of Petrograd where strong garrisons were quartered became more active. They too passed resolutions calling for the convocation of the Second Congress of Soviets. The Soviets in Kronstadt, Yuryev and Reval adopted the fighting slogan: “All power to the Soviets!”

Thus, the Bolsheviks won the support of the immediate rear of Petrograd.

The Northern Front, like Finland, was ready to support the Bolshevik Party. The Petrograd workers insisted on the transfer of power to the Soviets. In Moscow where the election of the District Dumas had taken place shortly before, the Bolsheviks had polled more than half the votes. These elections were probably the surest indication of the profound change that had taken place in the temper of the masses. For Moscow was more petty bourgeois than Petrograd; the Moscow workers were more closely linked with the rural districts and were more susceptible to rural influences than the Petrograd proletariat. Consequently, the elections in which the Bolsheviks polled 14,000 soldiers’ votes out of a total of 17,000 were not only an indication of the readiness of the proletariat to fight, but also of the sharp change that had taken place in the temper of the rural population.

In the capitals, in the industrial centres around Moscow and Petrograd and among the troops at the front nearest to these centres, the Party of Lenin was backed by the majority of the electorate. From the Urals and the Donets Basin, from the Volga Region and the Ukraine also came glad tidings of complete readiness for the new, proletarian revolution.

The international situation had also undergone a change. Isolated cases of mutiny grew into incipient military insurrection. In Germany, where a draconic military regime prevailed, the crews of five large warships mutinied in September 1917. The crew of the cruiser Westfalen threw their captain overboard and abandoned the ship. The crew of the cruiser Nürnberg arrested the officers and put off for Norway with the intention of deserting, but some destroyers loyal to the government surrounded the rebel cruiser and compelled her to return to Germany, threatening to sink her if she refused to obey. The movement spread so rapidly that it was no longer possible to hush it up. The German government admitted in the Reichstag that mutiny was rife in the German navy.

The events in Germany were undoubtedly an indication of the change of temper among the revolutionary masses in Europe. They were a symptom of the fact that the whole world stood on the threshold of revolution.

“The crisis has matured,” wrote Lenin on September 29. “The whole future of the Russian revolution is at stake. The honour of the Bolshevik Party is at stake. The whole future of the international workers’ revolution for Socialism is at stake.

“The crisis has matured. . . .”[1]

Lenin decided that the crucial moment had arrived. The slogan of action—prepare for an armed insurrection—had become an instruction—act at once!

To cling to the Pre-parliament in such a situation was tantamount to betraying the revolution. Not daring to oppose the idea of insurrection openly, its opponents proposed that action be delayed until the Congress of Soviets met. But to postpone a decision on the question of power until the Congress of Soviets met meant betraying to the enemy the date set for the insurrection. This would have enabled the enemy to muster his forces and crush the centres and organisations of the insurrection. It meant, practically, inviting failure and surrendering the initiative to the enemy.

The idea of postponing the insurrection until the opening of the Congress of Soviets was advocated by Trotsky. On September 20, addressing the Petrograd Soviet, he said that the question of power would be decided by the Congress of Soviets. Previous to that Trotsky had been in favour of abolishing the “Council of Five,” as the Kerensky government was called, and of the Democratic Conference setting up a Provisional Committee.

To place any hopes in the ability of a conference manipulated by traitors to set up some kind of an “interim” government until the meeting of the Congress of Soviets meant falling into the compromisers’ trap and misleading the people at the decisive moment.

Next day, at a meeting of the Bolshevik group in the Democratic Conference, Trotsky again suggested that the question of power be deferred until the meeting of the Congress of Soviets.

Trotsky did not dare oppose armed insurrection openly, but actually, like Kamenev, he did all he could to prevent it. Like all the Mensheviks, he dreaded insurrection and imagined that it was possible to decide the question of power in a peaceful way. He argued that the refusal to allow the garrison to be withdrawn from the capital showed that the victory of the revolution was already three-quarters won. In effect, however, his stand was that the bourgeoisie should be kept in power. More than that; postponement of the insurrection until the meeting of the Congress of Soviets meant revealing all the plans to the enemy, disrupting the revolutionary ranks and cooling the ardour of the masses who were straining to go into battle.

Lenin denounced the would-be saboteurs of the insurrection in no uncertain terms. With the vigour of a revolutionary fighter certain of victory he denounced any postponement as treachery and attacked the recalcitrants with the determination of a leader who realised that the crucial moment had arrived. In a postscript to his article “The Crisis Has Matured,” written especially for the Central Committee, Petrograd Committee and Moscow Committee of the Party, he again and again, underscored certain passages, as for example:

“To wait for the Congress of Soviets is downright idiocy, for this means losing weeks; and weeks, even days, now decide everything. It means timidly renouncing the seizure of power, for on November 1-2 it will be impossible to do so (both politically and technically, for the Cossacks will be mobilised for the day of insurrection foolishly ‘appointed’ beforehand).

“To ‘wait’ for the Congress of Soviets is idiocy, for nothing will come, nothing can come of the Congress.”[2]

Again and again Lenin persistently and emphatically repeated his arguments in favour of an immediate insurrection: We have a majority in the country. The Soviets in both capitals are ours. The ranks of the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks are in a state of utter disintegration. We must advance slogans that will ensure us the complete support of the working people, viz., “Down with the government that is delaying peace!” “Down with the government that is suppressing the peasants’ revolt against the landlords!”

“The Bolsheviks are now assured of victory in the insurrection,” he urged. “. . . We can (if we do not ‘wait’ for the Congress of Soviets) strike suddenly, and from three centres, from Petrograd, Moscow and the Baltic Fleet. . . . We have thousands of armed workers and soldiers in Petrograd who can at once seize the Winter Palace and the General Staff Headquarters, the Telephone Exchange, and all the larger printing plants, from which nobody will be able to dislodge us; and we shall be able to carry on agitation in the army on such a scale that nobody will be able to combat this government of peace, land for the peasants, and so forth.”[3]

On receiving this letter the Central Committee, on October 3, decided to summon Lenin to Petrograd so as to be able to maintain constant and close contact with him.

Lenin himself was displeased with having to remain so far away from the struggle that was flaring up in the capital. Letters from Petrograd reached him after considerable delay, and newspapers arrived a day late. The leader of the proletarian revolution wanted to be closer to the maelstrom of revolutionary events. He expressed the wish to remove to Vyborg. He again disguised himself, even putting on a grey wig, and on September 17 left Helsingfors. In Vyborg Lenin stayed with a Finnish Social-Democrat named Laatukka, the editor of the local Social-Democratic newspaper, who lived on the outskirts of the town. Here he continued tirelessly to write, instruct and spur on his comrades.

On October 5, the Central Committee of the Party decided, with only one dissenting vote, i.e., Kamenev’s, that the Bolshevik group should withdraw from the Pre-parliament at its very first session.

At the same meeting, the Central Committee decided to postpone the Northern Congress of Soviets to October 10 and to convene it not in Finland, as had been previously decided, but in Petrograd, and that the Petrograd Soviet should take part in the proceedings of this Congress. It also decided to invite representatives from the Moscow Soviet. In this way the Central Committee emphasised the importance it attached to the Northern Congress of Soviets as a sort of general review of the forces before going into action. Its decisions were to serve as a model for all the other Regional Congresses of Soviets; and it was to be a means of mobilising the masses in preparation for the insurrection.

In order to convert the decisions of the Northern Congress of Soviets into definite instructions Stalin proposed that a conference of the Central Committee of the Party together with prominent Petrograd and Moscow Party workers be convened on October 10, the day the Northern Congress was to be opened. Stalin’s proposal was adopted and at the same time it was decided to refrain from convening a Party Congress as this would divert attention from the work of preparing for the insurrection. All forces had to be concentrated on one question, namely, the insurrection.

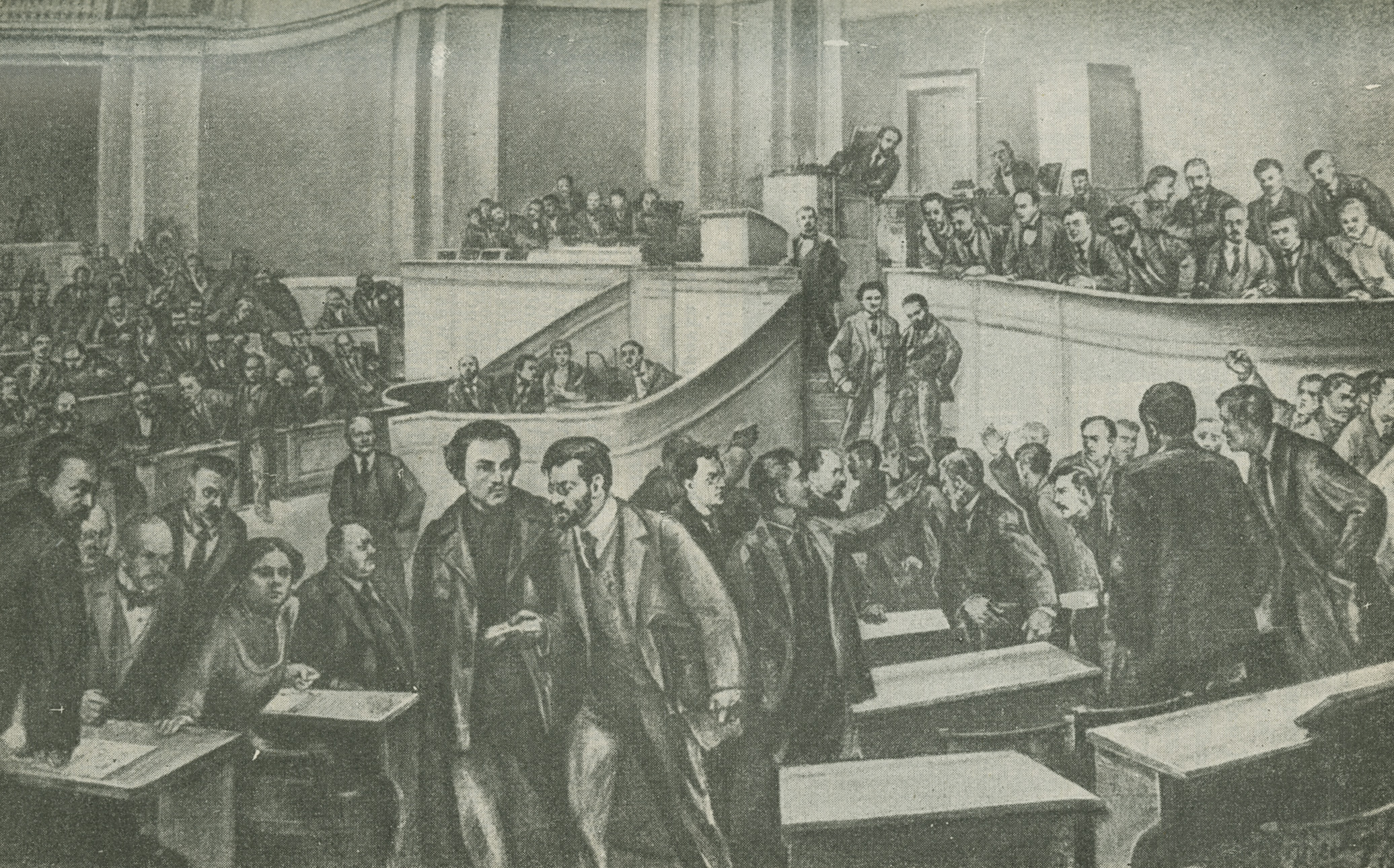

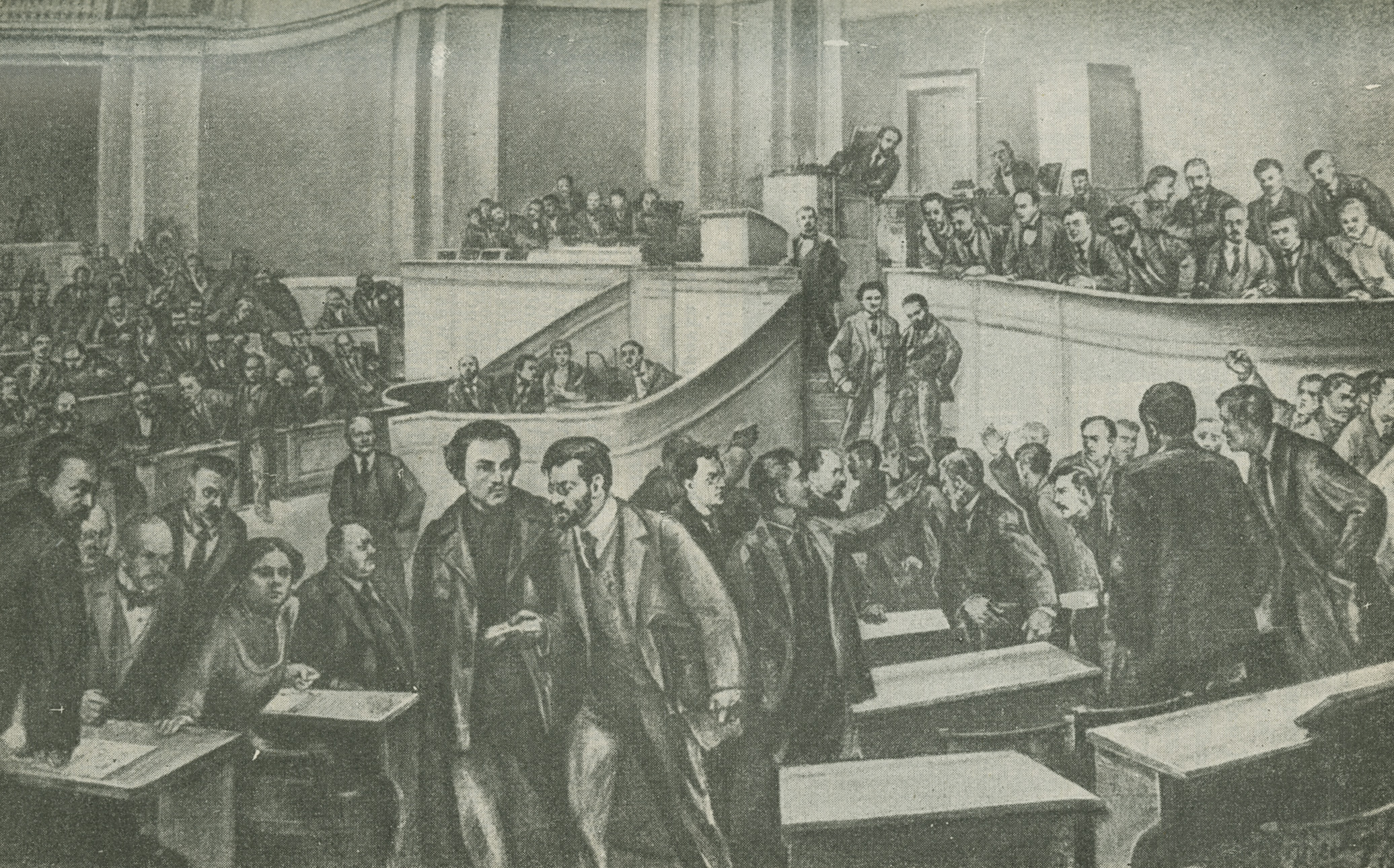

On October 7, the Pre-parliament was opened in the Mariinsky Palace. Representatives of the government, important government officials and representatives of the various public organisations in the capitals were present at the official opening. The Constitutional Democrats occupied the benches on the right and in the centre. These corpulent Moscow merchants, Petrograd industrial magnates and provincial landlords, kulaks and property owners had gathered to decide the “fate of the revolution.” Among them the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries were bowing and scraping, and all looked askance to the left, at the benches occupied by the Bolsheviks.

The session was opened by Kerensky, who in his speech—which was sympathetically applauded on the right and in the centre—bitterly complained that he was not being obeyed, and that the Bolsheviks had gained control in the army.

Kerensky was followed by the aged and senile Socialist-Revolutionary “grandmother” Breshko-Breshkovskaya, who wistfully recalled the tranquil days of the beginning of the revolution and tearfully compared them with the present turbulent times. The Right Socialist-Revolutionary Avksentyev, who had been elected President of the Council of the Russian Republic, delivered a fervid oration, which was followed by the dull and monotonous routine of electing secretaries and under-secretaries. Meanwhile the “leaders” of the Pre-parliament conferred with each other on how to prevent the Bolsheviks from speaking. The Bolsheviks persistently demanded the floor in order to read their declaration and at last Avksentyev called upon their spokesman. The Bolshevik declaration roused the bourgeois and compromiser deputies to fury. Beside themselves with rage when they heard the Kerensky government described as a “government for betraying the people” they raised a terrific uproar in order to drown the voice of the Bolshevik speaker.

“Get down!” shouted the infuriated Constitutional Democrats.

“Shut up, you Kishkins-Burishkins!” came the retort from the Bolshevik benches.

Their faces distorted with rage, co-operative society officials, Constitutional Democrats from the City Dumas enraged by their exposure, and compromiser members of the Executive Committees of Soviets who dared not stand for re-election, jumped from their benches and rushed towards the tribune with threatening gestures. Amidst the storm of abuse and insult raised by the Constitutional Democrats and Defencists, the Bolsheviks, after reading their declaration, retired from the hall.

“A safe journey!”—shouted someone in a voice in which irony was mixed with anger.

“We shall meet again!”—retorted the Bolsheviks prophetically.

The Central Committee succeeded in smashing the resistance of the saboteurs. The Party broke off connection with the Pre-parliament where the Kornilovites, screened by the compromisers, were making their preparations to attack the revolution. The working class, and working people generally, realised that all illusions about the possibility of peaceful evolution had to be abandoned. Self-sacrificing struggle alone could decide the outcome of the revolution.

“The first Kornilov plot was thwarted,” wrote Stalin after the Bolsheviks had withdrawn from the Pre-parliament, “but the counter-revolution was not crushed; it merely retreated, hid behind the back of the Kerensky government and entrenched itself in its new positions. . . .

“Let the workers and soldiers know, let the peasants and sailors know that it is now a fight for peace and bread, for land and liberty, against the capitalists and landlords, against the profiteers and marauders, against betrayers and traitors, against all who do not want to put an end once and for all to the Kornilovites who are now organising.

“The Kornilovites are mustering—prepare to resist!”[4]

On receiving the Central Committee’s summons to Petrograd, Lenin decided to travel by train to Raivola Station on the Finnish border and from there to ride on the footplate of Jalava’s engine, as he had done on the first occasion, to Udelnaya Station.

At 2:25 p.m. on October 7, Lenin, again in disguise, boarded the train. It was arranged that he and his companion, Rahja, should not go into the car but remain on the outside platform and, that Rahja should speak to Lenin in Finnish and that Lenin would reply now and again in the monosyllables “jo” or “ei” which meant “yes” or “no.”

The railway car was crowded. As arranged, Rahja spoke to Lenin in Finnish, but Lenin’s replies were quite out of place. Where he should have said “yes” he shook his head in the negative, and where he should have said “no” he uttered a curt “yes.”

The journey to Raivola passed without mishap, however. Leaving the train, Lenin and his companion walked down the line to the place where Jalava was fuelling his engine, about a kilometre and a half from the station. Lenin hid behind a bush while his companion climbed to the footplate. Jalava whispered in alarm that two suspicious individuals were watching the engine and suggested that Lenin and Rahja should walk back to the station and that he should pick them up on the way. Lenin retraced his steps along the tracks. Only one minute remained before the departure of the train, but Jalava’s engine had not yet arrived. At last it came puffing up at full speed. Drawing level with Lenin, Jalava sharply applied the brakes and the engine slowed down. Lenin climbed on to the footplate and the engine slowly glided towards the waiting train. Another moment, and they were off.

Lenin reached the suburban station of Udelnaya at night and walked to the Vyborg District of Petrograd. The first thing he requested on his arrival was an interview with Stalin. In the course of this interview, which took place on October 8 and lasted several hours, Stalin informed Lenin of how the preparations for the insurrection were progressing. Lenin eagerly questioned Stalin in detail about the temper prevailing among the armed forces and in the factories.

It was found impossible to convene the Party Conference which had been arranged for October 10, and a meeting of the Central Committee took place instead. Twelve persons were present at the meeting. Lenin too was present, this being his first attendance at a meeting of the Central Committee since the July days. When he arrived he was unrecognisable. He was clean-shaven and wore a grey wig which now and again he smoothed with both his hands. The assembled comrades congratulated him on his safe arrival and expressed their admiration at the skill with which he had succeeded in evading the vigilance of Kerensky’s sleuths.

As soon as the first raptures over the reunion were over, Lenin, who had already been informed of events by Stalin, suggested that the meeting proceed to discuss the main question.

Not having attended a meeting of the Central Committee for three months Lenin was keenly interested in the reports on latest developments. Comrade Sverdlov reported on the situation on the Northern and Western Fronts. There, the general temper was Bolshevik, he said. The Minsk garrison was on our side, but there was something in the wind there; mysterious negotiations were proceeding between General Headquarters and Front Headquarters. Cossacks were being concentrated around Minsk and anti-Bolshevik agitation was being conducted. Evidently, preparations were afoot to surround and disarm the revolutionary troops.

When Sverdlov finished speaking Lenin rose and reviewed the situation.

He again emphasised the importance of making thorough technical preparations for the insurrection and expressed the view that what had been done hitherto was inadequate. The political situation had matured; the people were expecting action, they were tired of resolutions and words. The agrarian movement was also developing in the direction of revolution. The international situation was such that the Bolsheviks must take the initiative. Summing up, Lenin said:

“Politically, the situation has fully matured for the transfer of power. . . .

“We must discuss the technical side. Everything depends on that.”[5]

In this review Lenin twice emphasised that the political situation had matured and that the point at issue was the choice of the moment for the insurrection. He definitely proposed that advantage should be taken of the Northern Congress of Soviets and of the readiness of the Bolshevik-minded garrison in Minsk for the purpose “of commencing decisive operations.”[6]

He was convinced that immediate action was necessary as further delay “meant death.” He proposed that advantage should be taken of any occasion that arose to begin—in Petrograd, Moscow, Minsk or Helsingfors, it did not matter where. But irrespective of the circumstances, no matter what the occasion for the insurrection might be, or where it started, the decisive battle would have to be fought in Petrograd, the political centre of the country, the hearth of the revolution.

Thus, Lenin had already in mind the question of the date of the insurrection; both for him and the Central Committee the question of the insurrection as such was a settled matter.

Lenin formulated his views in a brief resolution in which the Party directions were set forth with exceptional lucidity and precision. The resolution read as follows:

“The Central Committee affirms that both the international situation as it affects the Russian revolution (the mutiny in the German navy, which was an extreme manifestation of the growth of the world Socialist revolution all over Europe, and the threat of the imperialist world with the object of stifling the revolution in Russia) and the military situation (the undoubted determination of the Russian bourgeoisie and Kerensky and Co. to surrender Petrograd to the Germans), as well as the fact that the proletarian party has secured a majority in the Soviets—all this, taken in conjunction with the peasant revolts and the swing of public confidence towards our Party (the elections in Moscow), and, finally, the obvious preparations being made for a second Kornilov affair (withdrawal of troops from Petrograd, dispatch of Cossacks to Petrograd, encirclement of Minsk by Cossacks, etc.)—all this places armed insurrection on the order of the day.

“Affirming, therefore, that armed insurrection is inevitable and that it has fully matured, the Central Committee instructs all Party organisations to be guided accordingly and to discuss and decide all practical questions from this standpoint (the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region, the withdrawal of troops from Petrograd, action in Moscow and Minsk, etc.).”[7]

Lenin’s resolution was carried by ten votes against two. On Dzerzhinsky’s motion it was decided “to set up for the purpose of political guidance for the immediate future a Political Bureau to consist of members of the Central Committee.”[8]

Only two members of the Central Committee opposed Lenin at this meeting. They were Kamenev and Zinoviev who raised a number of objections to what Lenin had said. The international situation, they argued, was unfavourable for us; the working class would not render active support and the Germans could easily come to an arrangement with their enemies and hurl themselves against the revolution; we did not have a majority in the country; only the workers and a section of the soldiers were on our side, the rest were doubtful. It would be better, they urged, to take up a defensive position; the bourgeoisie would not dare to call off the Constituent Assembly, and there we would have one-third of the seats; the petty-bourgeoisie were inclining towards the Bolsheviks; in conjunction with the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries we could form a bloc which would predominate in the Constituent Assembly and pursue our policy.

Kamenev and Zinoviev simply ignored all that the Russian working class had suffered in the struggle against tsarism and the bourgeoisie.

In ceaseless battle against the opportunists Lenin had perseveringly taught that it was not enough to recognise the class struggle. Even the bourgeoisie did not deny the class struggle. But only those who recognised the class struggle carried to the stage of the dictatorship of the proletariat were genuine Marxists. Bolshevism had grown and become strong and steeled precisely in the struggle for the dictatorship of the proletariat.

On the very eve of the stern and decisive event that was to mark the culminating point of an entire historical stage of the struggle waged by the Bolshevik Party, Kamenev and Zinoviev took up the treacherous position of the Mensheviks and of Kautsky, i.e., of peaceful evolution towards Socialism through Parliament, in this case through the Constituent Assembly. Virtually, Zinoviev and Kamenev were strenuously defending capitalism.

Like all traitors, they could see only the mighty array of the enemy’s forces.

The enemy, they argued, had at his command well-trained forces, artillery, Cossacks, shock troops and the army. . . . As for ourselves . . . “there is no fighting spirit even in the factories or in the barracks.”[9] Verily, the coward is afraid of his own shadow!

The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party administered a stern rebuff to these defenders of capitalism. Nobody supported these capitulators. Lenin’s resolution became an instruction for the entire Bolshevik Party.

This meeting of the Central Committee ended late at night. Outside it was cold and raw. Here and there a street lamp gleamed fitfully through the mist. Comrade Dzerzhinsky removed his cape and put it over Lenin’s shoulders. Lenin wanted to protest, but Dzerzhinsky insisted.

“No excuses, now! Please put this cape on, otherwise I shall not let you out,” he said.[10]

Lenin lived at a considerable distance from the place of the meeting and seeing that it was so late he decided to spend the night with a worker who occupied a tiny room in Pevcheskaya Street, nearby, the site now occupied by the huge Electropribor Plant.

The worker offered Lenin his bed, but Lenin categorically refused and lay down on the floor, using a couple of books for a pillow.

[1] V. I. Lenin, “The Crisis Has Matured,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 276.

[2] Ibid., p. 277.

[3] Ibid.

[4] J. Stalin, “The Counter-Revolution Is Mobilising—Prepare to Resist!” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 583.

[5] V. I. Lenin, “Meeting of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P., October 23, 1917,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book II, p. 106.

[6] Ibid., p. 107.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Minutes of Proceedings of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P., August 1917-February 1918, State Publishers, Moscow, 1929, p. 100.

[9] Ibid., p. 107.

[10] E. Rahja, “Lenin in 1917.” Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

Previous: The Course is Set for Insurrection

Next: The Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region