On October 10, while the meeting of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party was proceeding, delegates began to assemble in the Smolny for the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region. Sverdlov had informed the organisers and leaders of the Congress that it would be necessary to postpone the opening until October 11. Consequently, on the evening of the 10th, only a preliminary conference of the delegates was held, at which a Credentials Committee was elected and the agenda endorsed.

Delegates had arrived from Petrograd, Moscow, Novgorod, Staraya Russa, Borovichi, Reval, Yuryev, Archangel, Volmar, Kronstadt, Gatchina, Tsarskoye Selo, Chudovo, Sestroretsk, Schlüsselburg, Vyborg, Helsingfors, Narva, Abo and Kotka. No representatives were present from Petrozavodsk, Tikhvin, Pavlovsk, Venden and Pskov.

In all there were 94 delegates, of whom 51 were Bolsheviks, 24 “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, four Maximalist Socialist-Revolutionaries, one Internationalist-Menshevik, ten Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and four Defencist-Mensheviks.

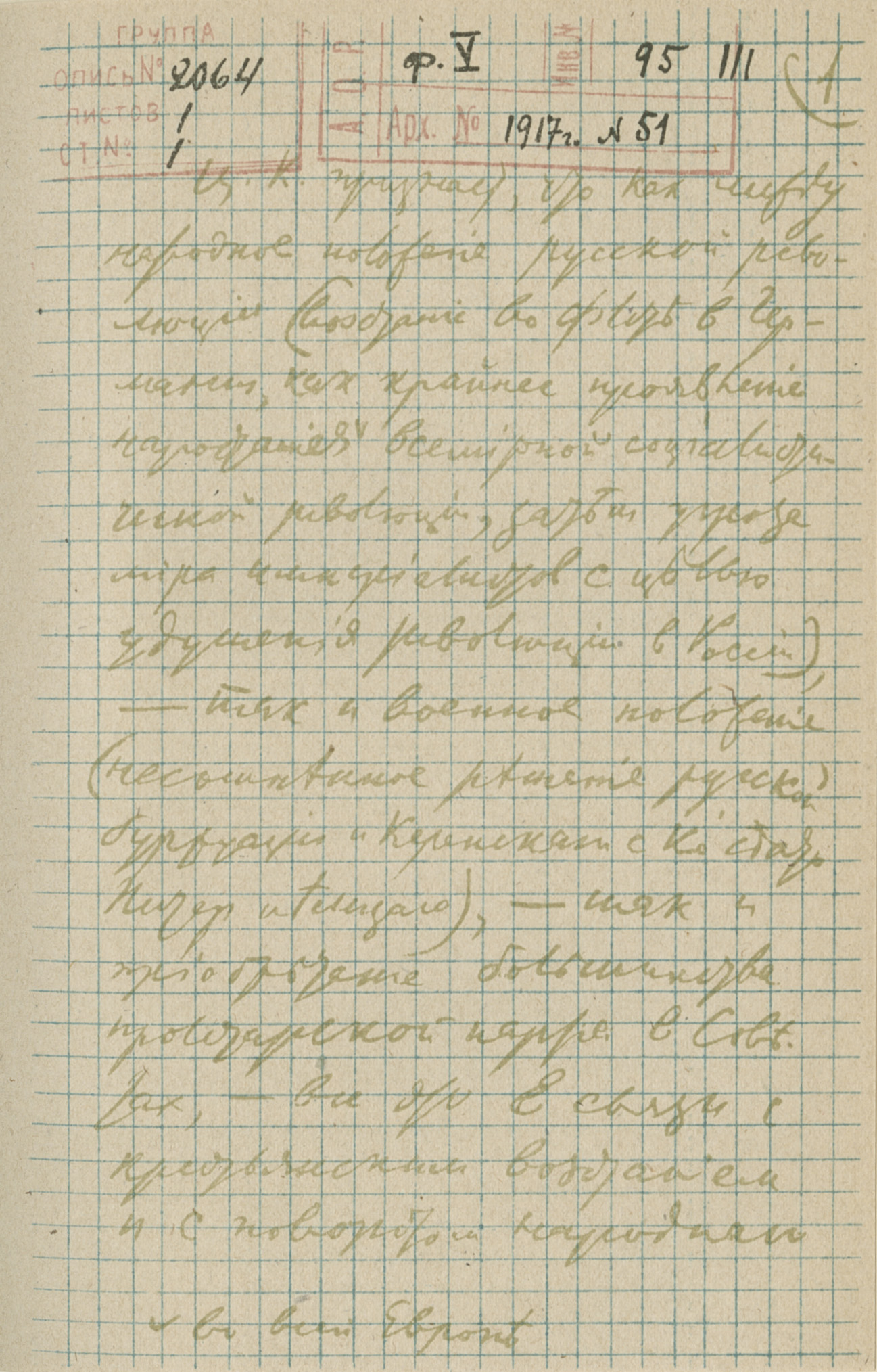

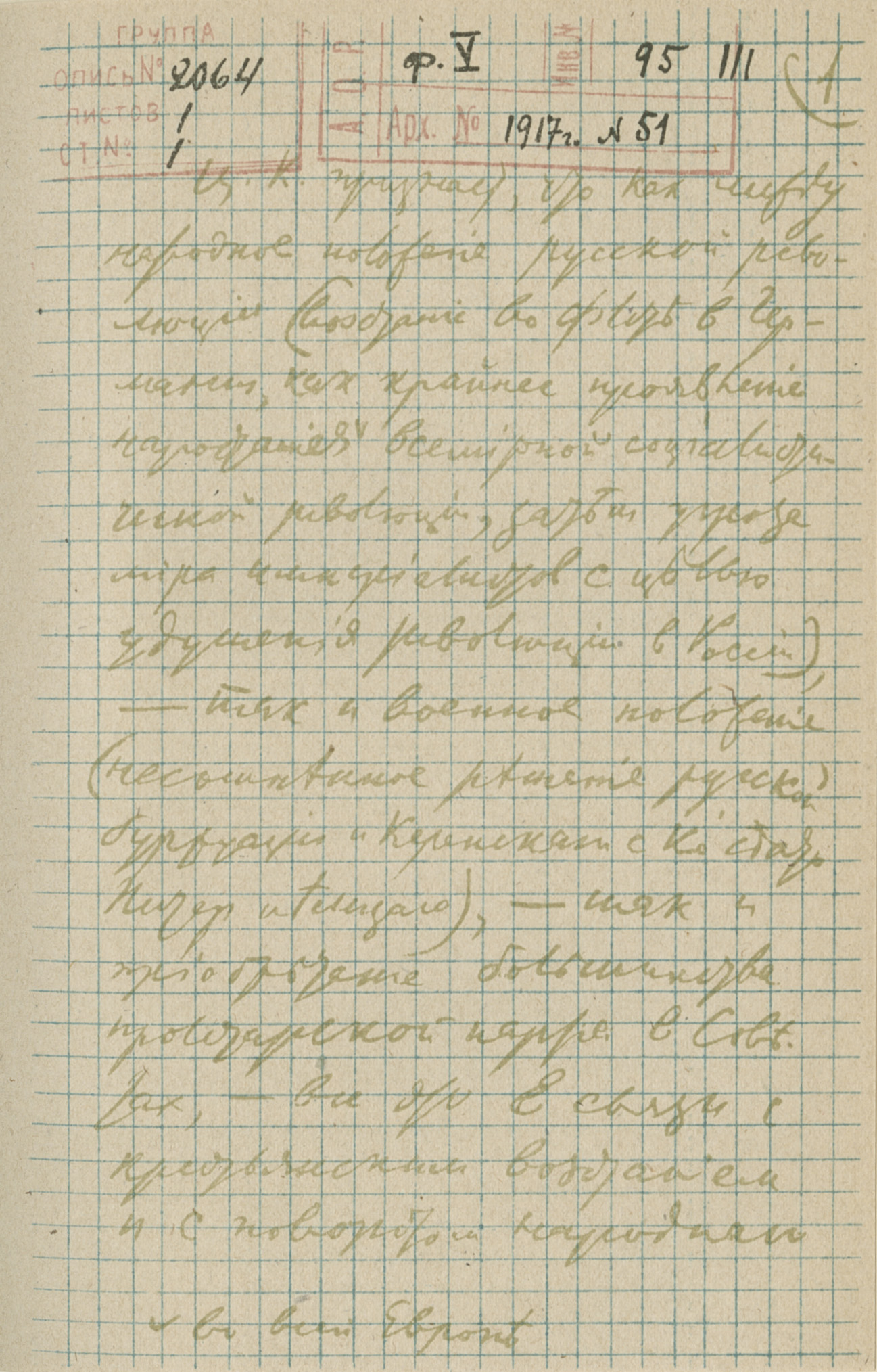

Lenin attached exceptional importance to this Congress. On October 8 he addressed a special letter to “the Bolshevik comrades participating in the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region,” in which he stated that the Congress must be prepared to seize power and launch the insurrection.

“We must not wait for the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which the Central Executive Committee may postpone till November,” he wrote; “we must not tarry and allow Kerensky meanwhile to bring up still more Kornilov troops.”[1]

No further delay could be permitted. The moment for active operations had arrived. . . .

Again and again Lenin reiterated the arguments in favour of insurrection. It was no longer a matter of passing new resolutions.

“It is now a question,” he wrote, “of an insurrection which can and must be decided by Petrograd, Moscow, Helsingfors, Kronstadt, Vyborg and Reval. Near Petrograd and in Petrograd—this is where this insurrection can and must be decided upon and carried out as thoroughly as possible, with as much preparation as possible, as quickly as possible and as energetically as possible.”[2]

Lenin then briefly drafted the plan of insurrection. He proposed that the regiments from the nearest garrisons be brought to Petrograd, that the fleet be summoned from Kronstadt, Helsingfors and Reval, that the Kornilov units be crushed, that both capitals rise and overthrow the Kerensky government, set up their own government, immediately offer peace to the belligerent countries and transfer the land to the peasants.

The leader of the revolution also indicated the slogan of insurrection.

“Kerensky,” he wrote, “has again brought the Kornilov troops to Petrograd in order to prevent power from passing to the Soviets, to prevent the immediate offer of peace by this power, to prevent the immediate transfer of the land to the peasantry, to deliver Petrograd to the Germans while he himself runs off to Moscow! This is the slogan of the insurrection which we must circulate as widely as possible, and which will meet with tremendous success.”[3]

Lenin’s letter was discussed at a meeting of the Bolshevik group at the Congress. The group met in the morning on October 11, after the decisive session of the Central Committee of the Party, in the large room No. 18, in the Smolny, where the Bolsheviks usually held their meetings.

On behalf of the Central Committee a report was made on the measures which had been adopted. Avoiding the word “insurrection,” the speaker stated that the time for general talk about transferring power to the Soviets had passed and that the time had arrived to decide definitely what occasion was to be seized upon to carry this out. Probably the Congress would have to be the organisation to launch the insurrection.

The leaders of the Congress had learned from Comrade Sverdlov the nature of the decision reached by the Central Committee. Many of the Bolshevik delegates to the Congress had also heard about it. This report thus brought them face to face with the question of insurrection. Everybody sensed that the decisive moment had arrived, and every delegate involuntarily looked round at the slightest rustle, as if expecting the door to open and the call to battle ring out.

That same evening the Congress was opened.

The voices of the speakers participating in the discussion vibrated with fervour and emotion. Speaking of the danger which threatened Petrograd the representative of the Petrograd Soviet stated that the Provisional Government intended to withdraw two-thirds of the Petrograd garrison. “The fate of Petrograd is in the balance!”—he exclaimed.[4]

A sailor from the Baltic Fleet followed. He said: “To withdraw the garrison from Petrograd means betraying the revolution.”

Addressing the delegates, he added:

“The Baltic Fleet says to you: remain here and defend the interests of the revolution. Remain here and guard the revolution!”

The last words of this call were drowned by thunderous applause. The Congress sent a message of greeting to the Baltic Fleet.

The Moscow representative declared that in the moment of danger the Moscow garrison and proletariat would not remain mere idle spectators.

“In Finland, the Soviets have already become organs of revolutionary power,” reported the representative of the Finnish Regional Committee. “The Regional Committee,” he added, “controlled the work of the government officials. Not a single order issued by the Provisional Government is carried out in Finland unless it is countersigned by the Commissar of the Regional Committee.”[5]

One after another delegates from the various districts addressed the Congress. The representatives of the Soviets in the Petrograd Gubernia and of the Soviets of Helsingfors and Kronstadt greeted the Congress; one and all unanimously urged the necessity of convening the Second Congress of Soviets at the earliest date.

Suddenly, a jarring note was struck in this militant atmosphere when the Menshevik Mukhanov rose on a point of order to make a declaration to the effect that for a number of reasons the Menshevik group felt obliged to withdraw from the Congress.

The effect produced on the delegates by this statement was the opposite of what its sponsors had desired. It was met with derision and the Congress calmly decided to postpone discussion on it until the next session, whereupon the hapless Menshevik orator left the rostrum in utter confusion. His place was taken by a representative of the Vyborg garrison, a Bolshevik named Golovov, who reported to the Congress:

“In Vyborg, power is now in the hands of the Soviet. The Soviet has captured the Telegraph Office and has dismissed the Army Corps Commander and the commandant of the fortress.”[6]

According to the report of the delegate Ryabchinsky, the same militant spirit prevailed in Reval.

The compromisers, however, persisted in their efforts. On behalf of the Novgorod delegation the Menshevik Abramovich requested leave to speak on a matter of urgency. His delegation, he said, had received a telegram from the Executive Committee of the army organisations of the Northern Front ordering them to withdraw from the Congress.

The delegates, however, did not wish to withdraw. Krylov, the delegate from Borovichi, a town in the Novgorod Gubernia, mounted the rostrum and sharply rebuking Abramovich stated that he refused to submit to the order of the compromising Executive Committee and assured the Congress that

“the Borovichi garrison will back the demands of the Northern Congress with armed force.”[7]

And again to the platform, one after another, came an endless procession of soldiers, sailors and workers, many of them delegates direct from the front who had come to the Congress secretly, overcoming the numerous obstacles that the Army Command had placed in their way. At the Congress there were representatives of the “trench dwellers” of the Western, South-Western and Rumanian Fronts. All hastened to add their voices to the demands of the soldiers and sailors of the Northern Region:

“All power to the Soviets!”

A representative of the Volhynia Regiment spoke on behalf of the Petrograd garrison.

“The regiment will not leave Petrograd as long as the present government remains in power,” he said. “If we have to leave, we’ll take the Provisional Government with us,” he added amidst a roar of laughter and applause.[8]

The demand of the soldiers and workers was fully supported by the representatives of the peasant organisations at the Congress. The representative of the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies called for the immediate transfer of power to the Soviets. The demand of the Petrograd peasants was backed by the peasant delegate from the Kherson Gubernia, who described the hard lives of the Kherson peasants and stated that the latter had no confidence in the Provisional Government and were determined not to deliver a single ounce of grain until the Soviets took power.[9]

With this the first session of the Congress was brought to a close. This session had revealed the revolutionary fighting spirit of the fleet, the garrisons and the factories in the Northern Region, and the fact that they were entirely on the side of the Bolsheviks. Even the counter-revolutionaries and the compromisers were reluctantly compelled to admit this. Bourgeois newspapers like Dyen and Utro Rossii, in their reports of the first day’s proceedings of the Congress, were obliged to concede that the Bolsheviks were the victors.[10]

The militant spirit of the Congress frightened the compromisers. Next morning all their newspapers published a decision passed by the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet to the effect that the Congress was “unauthorised.” Until this moment, the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik Central Executive Committee had raised no objection to the convocation of the Congress, but as soon as its Bolshevik composition and genuinely revolutionary temper became evident the compromisers raised a howl of protest. The Central Executive Committee stated that it could regard the Congress only as a private conference on the ground that it had been convened by the Helsingfors Soviet “which had no authority to do so,” that a representative of the Moscow Soviet was present, whereas several Soviets in the Northern Region were not represented, and lastly, that the Central Executive Committee had not been aware that the Congress was being convened.

Next morning, on October 12, the compromisers arrived at the Congress with radiant faces. They rubbed their hands with glee and gathered in the lobbies whispering to each other and triumphantly waving the morning newspapers which contained the decision of the Central Executive Committee stating that the Congress was unauthorised. When the session was opened the Mensheviks asked for the floor. Bogdanov, the first speaker, declared that the Mensheviks associated themselves with the decision of the Central Executive Committee and refused to take any further part in the proceedings of the Congress. They would remain at the Congress merely “for the purpose of obtaining information.”

This statement by the Menshevik group met with no sympathy from the delegates. Here and there impatient voices were heard demanding: “Let’s get down to business!”

Even the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries dared not openly support the Mensheviks.

On the motion of the Bolshevik group the Congress passed a resolution denouncing the treacherous conduct of the Central Executive Committee, after which it proceeded to discuss the political situation.

The resolute proposal of the Bolsheviks that power be immediately transferred to the Soviets frightened the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries.

“The Bolsheviks want the question of power to be decided in the streets, and refuse to have the question settled in a parliamentary way,” timidly complained Kolegayev.[11]

This leader of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, however, was opposed by a rank-and-file member of his party, a Kronstadt sailor named Shishkov, who expressed the opinion that the Bolsheviks and the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries should fight jointly to capture power. The representative of the 33rd Army Corps read to the Congress the instructions he had received from the soldiers of this Corps stating that they were expecting the immediate conclusion of peace, the confiscation of private land, the ruthless taxation of big capital and large incomes, and the confiscation of war profits.[12]

The Congress passed the following resolution:

“The coalition government has disorganised, bled and tortured the country. The so-called Democratic Conference has ended in a miserable fiasco. The fatal and treacherous policy of compromise with the bourgeoisie is indignantly rejected by the workers, soldiers and politically conscious peasants. . . . The hour has arrived when only the most resolute and unanimous action on the part of all the Soviets can save the country and the revolution and settle the question of the central authority. The Congress calls upon all the Soviets in the region to commence active operations.”[13]

In a comprehensive report on the military and political situation a Bolshevik representative informed the sailor, soldier and worker delegates of Lenin’s plans and of the decision adopted by the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party regarding armed insurrection. He did not employ the term “insurrection,” but in words suitable for the conditions under which the Congress was being held he stated that the Provisional Government must be removed and that the Soviets must take power.

A representative of the Petrograd Bolsheviks informed the Congress that a Military Revolutionary Committee was being formed in Petrograd, which would be in control of all the armed forces. In response to this, the representative of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary group stated that his group supported the proposal to form Soldiers' Military Revolutionary Committees.

The Congress issued an appeal to the garrisons in the Northern Region to take all measures to put themselves in proper fighting trim. It also called upon the local Soviets to follow the example of the Petrograd Soviet and form Military Revolutionary Committees for the purpose of organising the military defence of the revolution.

The Congress paid special attention to the land question and issued a call to the peasants urging them to support the struggle for power. In this call the Congress said:

“The peasants should know that their sons in the trenches, in the barracks and on the warships, and the workers in the factories and mills are on their side, and that the days of decisive battles are drawing near, when the revolutionary workers, soldiers and sailors will rise in the struggle for land, for freedom and for a just peace. They will establish the workers’ and peasants’ government of Soviets of Peasants’, Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.”[14]

On the motion of the Bolsheviks a decision was adopted to form a Northern Regional Committee for the purpose of ensuring the convocation of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets and to serve as the centre of the activities of all the Soviets in the region. The Committee consisted of 17 members of whom 11 were Bolsheviks and six “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries.

Before the Congress drew to a close numerous delegations appeared in the hall. The rostrum suddenly seemed to have been enclosed in a ring of bayonets. These were representatives of the Lettish Rifle Regiments, who had come to greet the Congress.

“From the very first day of the revolution,” said their spokesman “the Letts issued the slogan: ‘All power to the Soviets!’ and today, when revolutionary Petrograd is preparing to put this slogan into effect, the Lettish Rifles, 40,000 strong, are ready to render full support.”[15]

The Lettish speaker was followed by the representative from the Obukhov Works.

“Our plant wholeheartedly supports the Bolsheviks,” he assured the Congress.[16]

The declarations of all the delegations expressed but one thought, viz., indomitable determination to fight to the bitter end. The Letts, the sailors and the Petrograd workers all called for insurrection, and the hundreds of men who filled the Assembly Hall of the Smolny responded to these appeals with loud applause and cheers and the singing of the Internationale.

The compromising Central Executive Committee of Soviets tried to discredit the Congress and proclaimed that the decisions it had adopted were disruptive.

The compromisers realised that the Congress’s direct call to the Regimental Committees, to the soldiers, sailors, workers and peasants, to take the election of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets into their own hands was a veiled blow at the Central Executive Committee. This they feared most of all.

While the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region was in session an editorial article entitled “The Crisis in the Soviet Organisation” appeared in Izvestia, the organ of the Socialist-Revolutionary-Menshevik Central Executive Committee. This article contained the following passage:

“The Soviets were a splendid organisation for fighting the old regime, but they are totally incapable of undertaking the task of establishing a new regime; they lack experts, they lack the skill and ability to conduct affairs, and lastly, they lack the organisation.”[17]

Terrified by the successes achieved by the Bolsheviks, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks tried to persuade the masses that as political organisations the Soviets were absolutely incapable of governing the country. In the above-mentioned article we read further:

“We built the Soviets of Deputies as temporary hutments in which the entire democracy could find shelter. Now, in place of these hutments, we are building the permanent edifice of the new system, and naturally, people are gradually deserting the hutments for the more convenient premises as they are built storey by storey.”[18]

The compromisers rushed about in consternation, wailing in apprehension of the impending revolutionary storm. In fear and panic they blurted out the class content of their compromising policy, which was to use the Soviets as a means of holding back the masses from revolution until the bourgeoisie had taken the reins of government more firmly in their hands and had become masters of the situation in the country.

The faithfulness of these flunkeys of the bourgeoisie was at once appreciated in their master’s drawing room. Russkaya Volya, one of the leading organs of the counter-revolution, made the following sympathetic comment on the aforementioned Izvestia article:

“Only very recently . . . one could speak . . . about the Soviets only in the most respectful terms. Criticism of the Soviet organisations was regarded as an open manifestation of counter-revolution. At last, the day has come when not the ‘counter-revolutionary’ and not the ‘bourgeois’ press, but the organ of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets openly speaks about the demise of the Soviets.”[19]

The compromising “Socialists” and the diehard counter-revolutionary bourgeoisie found a common tongue. What the terrified flunkeys blurted out in a fit of panic was fully in accord with the plans of their counter-revolutionary masters. In organising a new offensive against the workers and peasants, the bourgeoisie demanded first of all the dissolution of the Soviets.

The counter-revolutionaries fully appreciated the enormous importance of the decision adopted by the Congress which had just drawn to a close. In its issue of the day after the Congress closed, the Moscow newspaper Utro Rossii wrote as follows:

“The Left Bolshevik temper of the Regional Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies which closed yesterday gives rise to the most alarming apprehensions.”[20]

And Dyen stated that “the provinces are responding, and in a most unambiguous manner” to the slogans issued by the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region.[21]

The Congress exercised a vast mobilising influence not only in the Northern Region but far beyond its borders. Immediately after the Congress the delegates returned to their respective localities and everywhere reported on its decisions and mobilised the forces of the revolution.

Following on the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region, Congresses of Soviets were held in a number of other regions and districts. And the keynote of all of them was: prepare for the struggle to transfer power to the Soviets.

[1] V. I. Lenin, “A Letter to Bolshevik Comrades participating in the Regional Congress of the Soviets of the Northern Region,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book II, p. 103.

[2] Ibid., p. 105.

[3] Ibid., p. 103.

[4] “The Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region,” Rabochy Put (Worker’s Way), No. 35, October 13, 1917.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “The Northern Regional Congress of Soviets,” Rech (Speech), No. 240, October 12, 1917.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] “The Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region,” Rabochy Put, No. 35, October 13, 1917.

[10] “The Regional Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Dyen (The Day), No. 187, October 12, 1917.

[11] “The Northern Regional Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Rech, No. 241, October 13, 1917.

[12] “The Voice of the Front. Instructions to Delegates of the XXXIII Corps.” Rabochy Put, No. 37, October 15, 1917.

[13] “The Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region,” Rabochy Put, No. 35, October 13, 1917.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., No. 37, October 15, 1917.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “The Crisis of Soviet Organisation,” Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, No. 195, October 12, 1917.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “The Soviet Is Dead,” Leading Article in Russkaya Polya (Russian Freedom), No. 243, October 13, 1917.

[20] “In the Smolny Institute,” Utro Rossii (Russia’s Morning), No. 247, October 14, 1917.

[21] S. Klivansky, “Preparation for Armed Insurrection,” Dyen, No. 189, October 14, 1917.

Previous: The Bolshevik Party's Directions

Next: Winning the Majority in the Country