The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party discussed Lenin’s letters on September 15. At this meeting, Kamenev, who was subsequently tried and executed as an enemy of the people, sharply opposed Lenin. He argued that Lenin was isolated from events, and demanded that Lenin’s letters should be burned as the “ravings of a lunatic.” The fighting call of the leader of the Party frightened those who had been opposing the Party and Lenin for a long time past.

The Central Committee strongly rebuffed this coward and traitor. Stalin moved that the letters be discussed and circulated among the larger Party organisations.

Kamenev thereupon moved a resolution in which he tried to put Lenin in opposition to the Central Committee. The resolution read as follows:

“The Central Committee, having discussed Lenin’s letters, rejects the practical proposal contained in them, calls upon all organisations to follow only the directions of the Central Committee and re-affirms its opinion that no street demonstrations of any kind are permissible in the present situation.”[1]

Kamenev thus tried to create the impression that Lenin did not express the opinion of the Central Committee.

This despicable manoeuvre failed, however. The Central Committee rejected Kamenev’s proposal.

Lenin’s letters were circulated among the larger organisations of the Bolshevik Party.

From the moment these letters were received, the Central Committee conducted its operations in the spirit of Lenin’s directions.

“Already at the end of September,” wrote Stalin on the occasion of the first anniversary of the Great Proletarian Revolution, “the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party decided to mobilise all the Party’s forces for the purpose of organising a successful insurrection.”[2]

A number of members of the Central Committee were appointed to inspect the forces of the Red Guard and its equipment, to ascertain the whereabouts of arms depots, and to register the military units and the temper of the men. The military organisation of the Bolshevik Party became more active. It established closer connections with the armed forces, formed Bolshevik groups among them, and conducted extensive propaganda and agitation among the soldiers and sailors.

All the preparations for the insurrection were carried on with the utmost secrecy. These matters were not discussed at ordinary meetings where resolutions were adopted and minutes taken. The conditions under which the Party was then operating, and the very nature of the task of preparing for insurrection, determined the specific character of these activities. Acting on Lenin’s advice, the members of the Central Committee established connections with Party workers in the localities and gave instructions to the most tried and tested of them. Sometimes highly important decisions were taken and organisational measures decided upon without any formal meeting and transmitted orally through trusted agents. Written instructions and reports were avoided as much as possible.

The Bolsheviks had their secret headquarters in the premises of the Sergiev Brotherhood in Furstadtskaya Street. These premises, ostensibly the offices of the Priboy Publishers, were situated next door to the church and, consequently, were jestingly referred to as “under the crosses.” Here, every day, representatives of local Bolshevik organisations came from all parts of Russia for assistance and advice. These premises also served as the base of operations of J. M. Sverdlov, in whose hands all the organisational contacts with the Central Committee of the Party were concentrated.

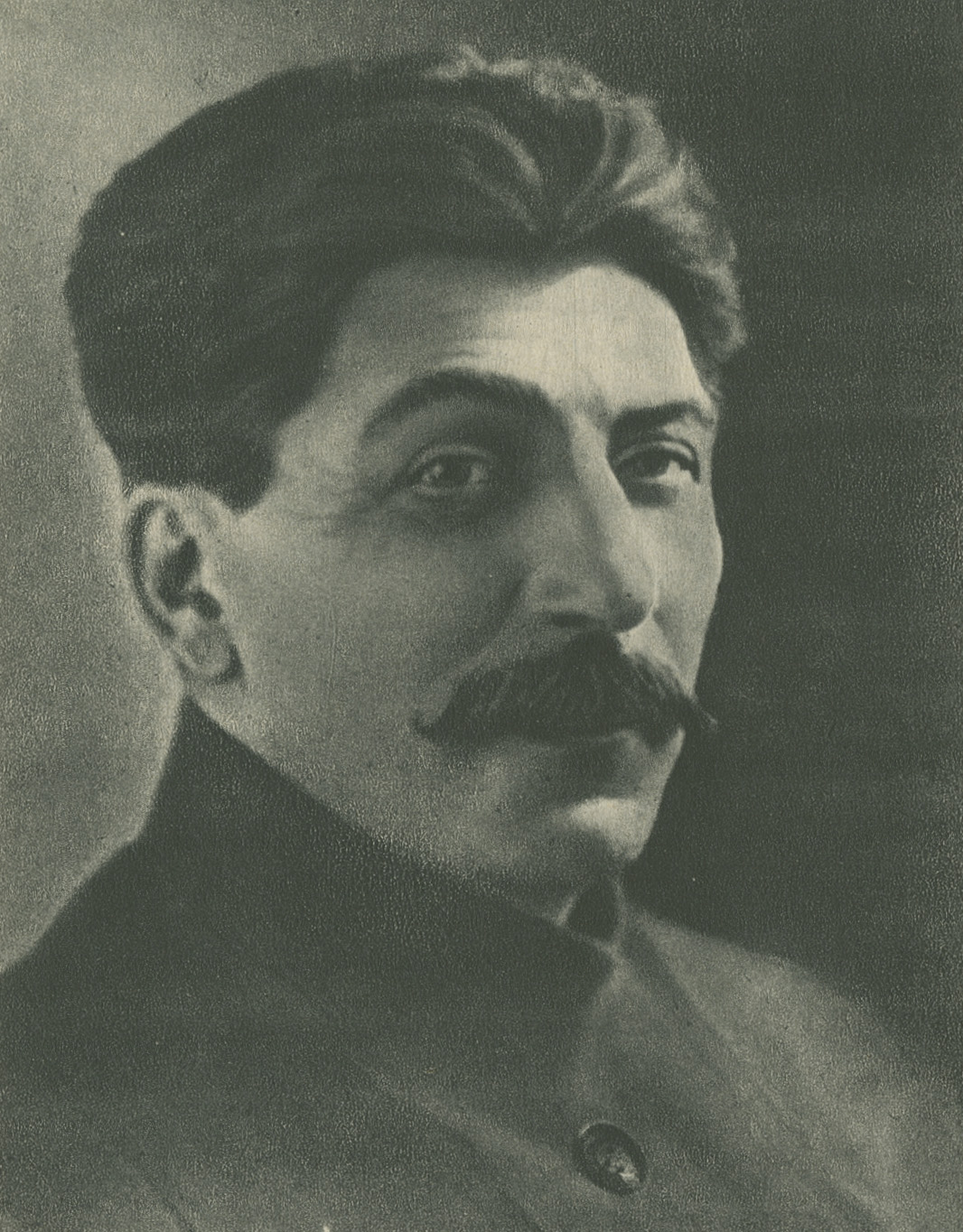

In this momentous period of the Party’s history, Stalin, as always, was by Lenin’s side organising victory. At the Sixth Congress of the Party Stalin had acted as the political leader of the Congress and Lenin’s right hand, whom he had entrusted with the task of carrying out the political line. On the Central Committee and on the editorial board of the central organ of the Party, Rabochy Put—the title adopted by Pravda owing to the persecution of the government—Stalin conducted organisational as well as propaganda work in pursuing and explaining the Leninist line of the Bolshevik Party. Under the conditions then prevailing, the role played by the central organ of the Party was an immense one, and the Party organisations obtained their main political bearings from the articles written by Lenin and Stalin.

The Central Committee had firmly and confidently set its course for insurrection, and this was immediately reflected in the columns of Rabochy Put.

Already on September 17, that is, two days after the first discussion of Lenin’s letter, Stalin, the editor of the central organ of the Bolshevik Party, in an article in Rabochy Put, wrote as follows:

“The revolution is marching on. Fired at in the July days and ‘buried’ at the Moscow Council, it is raising its head again, breaking down the old obstacles, creating a new power. The first line of trenches of the counter-revolution has been captured. After Kornilov, Kaledin is now retreating. In the flames of the struggle the moribund Soviets are reviving. They are once again taking the helm and leading the revolutionary masses.

“‘All power to the Soviets!’—such is the slogan of the new movement. . . .

“The straight question which life raises demands a clear and definite answer.

“For the Soviets or against them?”[3]

This was not a direct call for insurrection, that was impossible in a legally published newspaper. But the article as a whole breathed the Leninist spirit and called for a decisive struggle. Skilfully steering clear of the censorship, Stalin set a brilliant example of how to conduct popular agitation for an armed insurrection in the legal press.

“ . . . in Russia the decisive growth of a new power is taking place, a genuine power of the people, a genuinely revolutionary power which is waging a desperate struggle for existence,” wrote Stalin in the next issue of Rabochy Put. “On the one hand there are the Soviets, standing at the head of the revolution, at the head of the fight against the counter-revolution, which is not yet crushed, which has only retreated, wisely hiding behind the back of the government. On the other hand there is the Kerensky government, which is shielding the counter-revolutionaries, is coming to an understanding with the Kornilovites (the Constitutional Democrats!), has declared war upon the Soviets and is trying to crush them so as not to be crushed itself.

“Who will conquer in this struggle? That is the whole issue now. . . . “That is why the main thing now is not to draw up general formulas for ‘saving’ the revolution, but to render direct assistance to the Soviets in their struggle against the Kerensky government.”[4]

Stalin splendidly carried out the view expressed by Lenin in his first letter on armed insurrection, namely:

“We must think of how to agitate for this without expressing it openly in the press.”[5]

Stalin’s articles do not even mention the word “insurrection.” Nevertheless, every line of them contains a plain, convincing and open argument in favour of seizing power.

Adherence to Lenin’s line in the central organ of the Party again evoked opposition on the part of Kamenev. At the meeting of the Central Committee, held on September 20, Kamenev denounced what he regarded as the excessively sharp tone adopted by Rabochy Put and took exception to certain expressions used in the articles published in that paper. The Central Committee adopted a special resolution on this question which stated:

“. . . postponing a detailed discussion of the tone adopted by the central organ, the Central Committee affirms that its general trend wholly coincides with the Central Committee’s line.”[6]

The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party fully approved of the line pursued by the central organ which, in Stalin’s editorials, calmly and firmly carried out Lenin’s instructions. This was stressed by Lenin himself who wrote:

“We shall not at present dwell on the facts which testify to the rise of a new revolution, since, judging by the articles of our central organ, Rabochy Put, the Party has already made its views clear on this point. The rise of a new revolution appears to be commonly recognised by the Party.”[7]

By “new revolution” Lenin meant armed insurrection. He used this term in order to get around the censor.

Lenin gave this appraisal of the situation as early as September 22, after the publication of Stalin’s articles in the central organ of the Party. For Lenin and the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party, the slogan of armed insurrection was a slogan of action, and it was this idea that Stalin steadily and persistently stressed in the Party’s newspaper.

But the slogan of action demanded definite tactical measures. On September 21 the Central Committee of the Party discussed the tactical measures which followed from the fact that the course had been set for insurrection. One of these was the question of withdrawing from the Democratic Conference.

The Democratic Conference was on its last legs. It had dwindled down to meetings of the Presidium, at which the Menshevik Tsereteli, one of the Ministers of the Provisional Government, tried to persuade the delegates to support a coalition government. It had already been decided to substitute for the Democratic Conference a Council of the Russian Republic, consisting of members of the Democratic Conference.

Even before this new body had come into existence the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks hastened to describe it as a Preliminary, or Pre-parliament, hoping in this way to enhance its prestige and to create the impression among the people that Russia had already taken the path of bourgeois parliamentarism. In his articles Stalin described the Pre-parliament as a “Kornilovist abortion,” and the workers, jeering at the compromisers, dubbed it the “pre-bathhouse.”(*)

Thus, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party had to define its attitude towards this new Socialist-Revolutionary-Menshevik body. It decided to withdraw the Bolshevik representatives from the Presidium of the Democratic Conference (although not from the Conference itself), and to take no part in the proposed Pre-parliament. Owing to the fact that this motion was adopted by the narrow margin of nine votes against eight, the Central Committee resolved to leave the final decision to the Bolshevik group in the Conference.

That same day, September 21, a meeting of the Bolshevik group in the Democratic Conference was held at which Kamenev, Rykov and Ryazanov demanded that the group should remain in the Pre-parliament. The parliament must not be boycotted, they said; withdrawing from it was tantamount to insurrection. Trotsky, too, took up a definitely anti-Leninist position. He proposed that a decision on the question be postponed until the Congress of Soviets met; meanwhile, the group was not to enter the Pre-parliament.

Subsequently, Trotsky mendaciously claimed that this position coincided with Lenin’s boycott tactics.

Stalin adopted a clear and definite policy. To enter the Pre-parliament, he argued, would mean misleading the masses and creating the impression that a bloc with the compromisers was possible; it would mean strengthening the position of the very enemy whom we were preparing to overthrow. He proposed that the Pre-parliament should be boycotted and that all forces be concentrated on the struggle outside.

The opponents of the boycott, however, succeeded in winning over the Party’s “parliamentary” representatives, who had lost their political intuition. The members of the Democratic Conference were chosen not by the vote of the general electorate, but by public organisations, and the Bolshevik representatives were elected by Soviets, City Dumas, co-operative societies, etc. The atmosphere of compromise and the continuous pressure exercised by frightened petty-bourgeois had affected a number of the Bolsheviks. By a vote of 77 against 50 the Bolshevik group decided in favour of entering the Pre-parliament which was called into existence for the purpose of deceiving the masses.

The moment news of this decision reached Lenin he wrote a letter dealing with “the mistakes of our Party.” Hitherto Lenin had called upon the Bolshevik Party to leave the Conference and to concentrate on the factories and army barracks, but never before had he spoken of the Party’s mistakes. Now, however, he sharply attacked those who insisted on participating in this fictitious “parliament.”

“Not all is well at the ‘parliamentary’ head of our Party,” he wrote. “More attention must be paid to it; the workers must watch it more vigilantly. The jurisdiction of parliamentary groups must be more strictly defined.

“The mistake our Party has made is obvious. It is not dangerous for the fighting Party of the advanced class to make mistakes. It is dangerous, however, to persist in error, to refuse out of false pride to admit and correct mistakes.”[8]

The Central Committee returned to the question of the Democratic Conference on September 23, when the conduct of the “parliamentary” group was subjected to severe criticism. The Democratic Conference had adopted a resolution calling upon the government to conclude peace. It was obvious that the treacherous Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks, who had been talking about peace for so many months, had on this occasion merely signed another scrap of paper. The Bolsheviks at the Conference should have exposed this hypocritical step; but instead of doing so, they, headed by Kamenev and Ryazanov, voted for the resolution. The leaders of the group were dragging it along the path of parliamentarism.

The Central Committee condemned this conduct. To emphasise how impermissible it was even in minor things to create “parliamentary” illusions about the possibility of unity with the compromisers, the Central Committee stated in its resolution:

“Having heard the report that in reading the declaration [of the group in the Democratic Conference] Ryazanov had referred to Tsereteli as ‘Comrade,’ the Central Committee instructs the comrades to refrain in their public utterances from applying this term to people, whose designation as such may offend the revolutionary sentiments of the workers.[9]

Furthermore, the Central Committee decided to convene on the next day a joint conference of the Central Committee, the Petrograd Committee and the Bolshevik group in the Democratic Conference.

The conference was held as arranged and a resolution was adopted calling for:

“. . . the exertion of all efforts to mobilise the wide masses of the people organised by the Soviets . . . which are now militant class organisations, the transfer of power to which is becoming the slogan of the day.”[10]

Thus, the incorrect line adopted by the Bolshevik group in the Democratic Conference was rectified.

The opponents of insurrection, however, instead of fighting for the immediate seizure of power, clung to the idea of remaining in the Pre-parliament. This trend had to be exposed and defeated.

On September 24 the Central Committee called upon the Party to demand the immediate convocation of a Congress of Soviets to counter-balance the Pre-parliament, and in those localities where revolutionary temper was more pronounced to convene Regional and Area Congresses of Soviets without waiting for official sanction.

In a leading article in Rabochy Put, Stalin wrote:

“It is the duty of the proletariat as the leader of the Russian revolution to tear the mask from this government and to expose its real counter-revolutionary face to the masses. . . . It is the duty of the proletariat to close its ranks and to prepare tirelessly for the impending battles.

“The workers and soldiers in the capital have already taken the first step by passing a vote of no confidence in the Kerensky-Konovalov government. . . .

“It is now for the provinces to say their word.”[11]

On September 23, the day before the Central Committee of the Party adopted this resolution, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks on the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets, yielding to the pressure of the masses, had at last resolved to convene the Second Congress of Soviets, fixing the opening for October 20. Beginning with September 27, Rabochy Put daily printed the following appeal: “Comrades, workers, soldiers and peasants! Get ready for the All-Russian Congress of Soviets on October 20! Immediately convene Regional Congresses of Soviets!”

At its meeting on September 29, the Central Committee of the Party resolved to convene, on October 5, a Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region, that is, of Finland, Petrograd and the adjacent towns, where Bolshevik sentiment predominated. The object of the Congress was to accelerate the agitational and organisational preparations for armed insurrection.

[1] Minutes of Proceedings of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P. August 1917-February 1918, State Publishers, Moscow, 1929, p. 65.

[2] J. Stalin, On the October Revolution, Articles and Speeches, Party Publishers, Moscow, 1932, p. 19.

[3] J. Stalin, “All Power to the Soviets,” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., pp. 479-80.

[4] J. Stalin, “The Revolutionary Front.” Ibid., pp. 481-82.

[5] V. I. Lenin, “The Bolsheviks Must Assume Power,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 222.

[6] Minutes of Proceedings of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P. August 1917-February 1918, State Publishers, Moscow, 1929, p. 69.

[7] V. I. Lenin, “From a Publicist’s Diary,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 249.

[*] In Russian the Pre-parliament was called “Predparlament.” The workers referred to it sarcastically at “predbannik,” i.e., the ante-room used for undressing in a bathhouse.–Trans.

[8] V. I. Lenin, “From a Publicist’s Diary,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 254.

[9] Minutes of Proceedings of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P. August 1917-February 1918, State Publishers, Moscow, 1929, p. 73.

[10] Ibid., p. 81.

[11] J. Stalin, “The Government of Bourgeois Dictatorship,” in On the Road to October. Articles and Speeches, March-October 1917, 2nd ed., State Publishers, Leningrad, 1925, p. 178.

Previous: Lenin’s Call for Insurrection

Next: The Bolshevik Party's Directions