t was late in the autumn of 1917. At the front, in the cold and muddy trenches, millions of soldiers cursed the Provisional Government and gloomily asked themselves whether they would have to spend a fourth winter under these conditions. At night, in the countryside, the sky was aglow with the glare of conflagrations. The sinister sound of the tocsin was heard. The toiling peasants, having lost all hope of receiving land from the bourgeois Provisional Government, were burning the mansions of the nobility, seizing their lands and sharing their farm property. In the towns, wave after wave of strikes followed in a constantly rising tide. The new revolution was approaching—the revolution which Lenin had foretold, anticipated and prepared for.

t was late in the autumn of 1917. At the front, in the cold and muddy trenches, millions of soldiers cursed the Provisional Government and gloomily asked themselves whether they would have to spend a fourth winter under these conditions. At night, in the countryside, the sky was aglow with the glare of conflagrations. The sinister sound of the tocsin was heard. The toiling peasants, having lost all hope of receiving land from the bourgeois Provisional Government, were burning the mansions of the nobility, seizing their lands and sharing their farm property. In the towns, wave after wave of strikes followed in a constantly rising tide. The new revolution was approaching—the revolution which Lenin had foretold, anticipated and prepared for.

After the demonstration in July 1917 was fired upon, Lenin, closely shadowed by counter-revolutionaries, was forced to go into hiding. During the first few days he took refuge in the modest apartment of the veteran Bolshevik, S. Y. Alliluyev, at No. 17a 10th Rozhdestvenskaya Street, Petrograd. Here, on the fifth floor, the leader of the Bolshevik Party occupied a small room, containing only one window. The Provisional Government offered a reward for Lenin’s apprehension; and since spies shadowed all the prominent members of the Bolshevik Party who maintained contact with Lenin, there was a danger that they might discover his whereabouts. Consequently, on July 11,* Lenin removed to a village near Sestroretsk. He was accompanied to the railway station in Petrograd by Comrades Stalin and Alliluyev.

“Before the third bell,” relates Comrade Alliluyev, “Vladimir Ilyich came out on to the platform of the last car. The train moved out, and Comrade Stalin and I stood on the platform watching our beloved leader slowly vanishing into the distance.”[1]

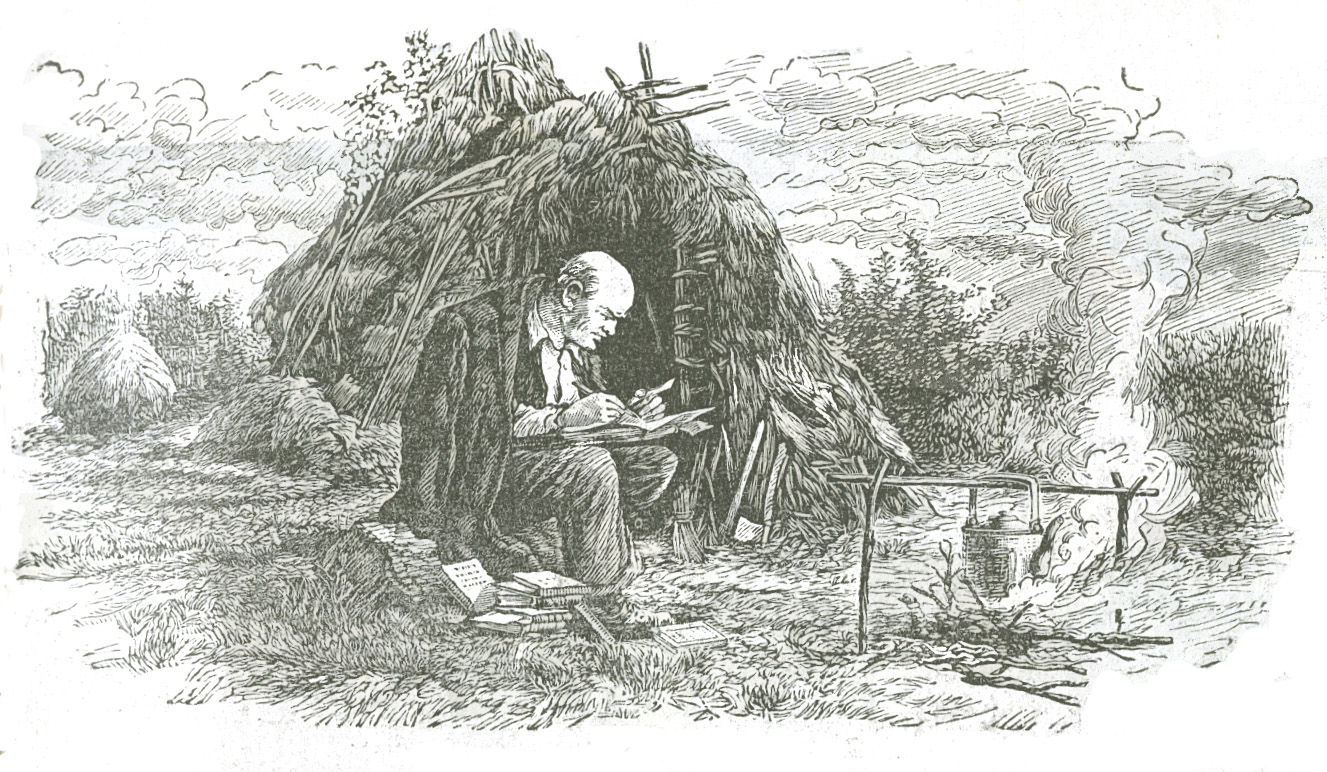

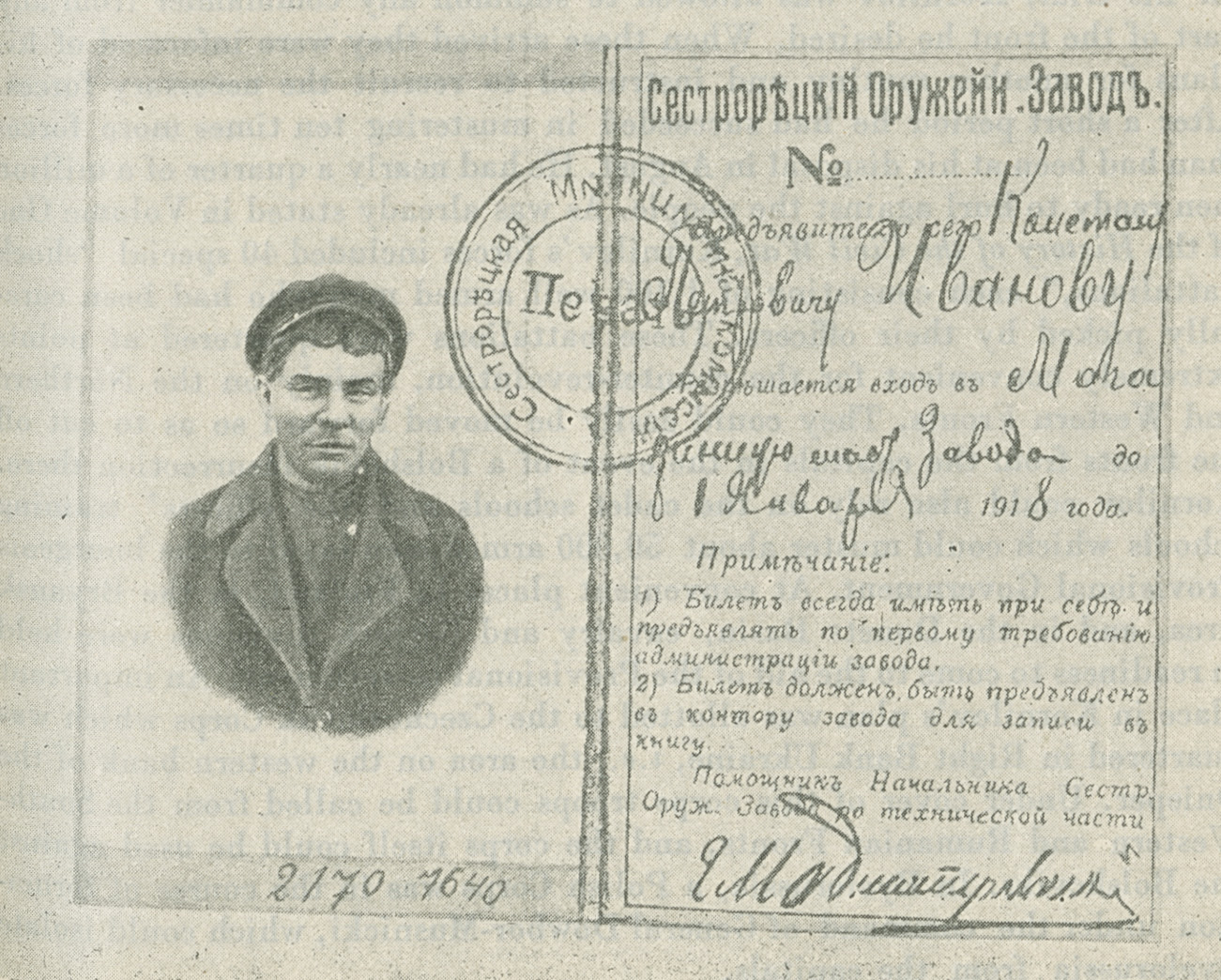

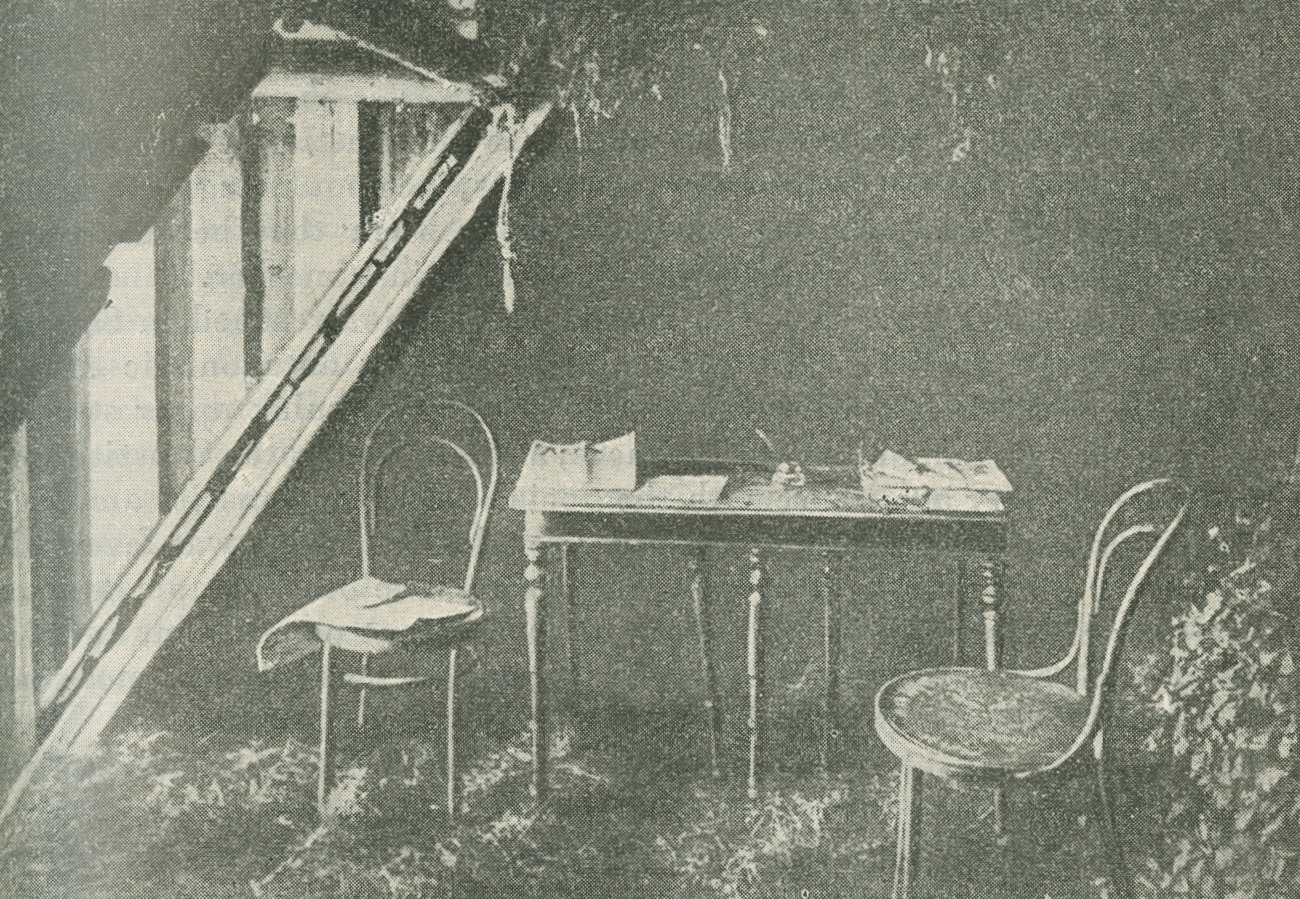

Lenin took up residence at a place near Razliv Station where there was a cottage with barn attached. The barn contained a hayloft access to which was had by means of a steep ladder. A table and chairs were hauled into the loft, and here Lenin took up his abode. But even this place was not safe. Residents of the nearby village, government officials and army officers, were constantly prowling round the place, angrily discussing Lenin’s alleged flight to Germany. So Lenin decided to find a safer hiding place in the surrounding forest. Beyond the station, on the bank of a small lake, there was a secluded glade. The local inhabitants or holiday makers rarely passed this way. A few haymakers lived close by and disguised as one of these and provided with an identity card made out to “Constantine Petrovich Ivanov,” Lenin removed to this place. Friends hollowed out a hayrick, converting it into a kind of shack, and this served as Lenin’s dwelling. Here he received newspapers and mail. Screened by a bush, and sitting at a fire over which a kettle was suspended, Lenin wrote his articles, which were duly dispatched to Petrograd. Sometimes, in the evening, the splash of oars was heard as representatives of the Central Committee of the Party rowed across the lake to visit Lenin.

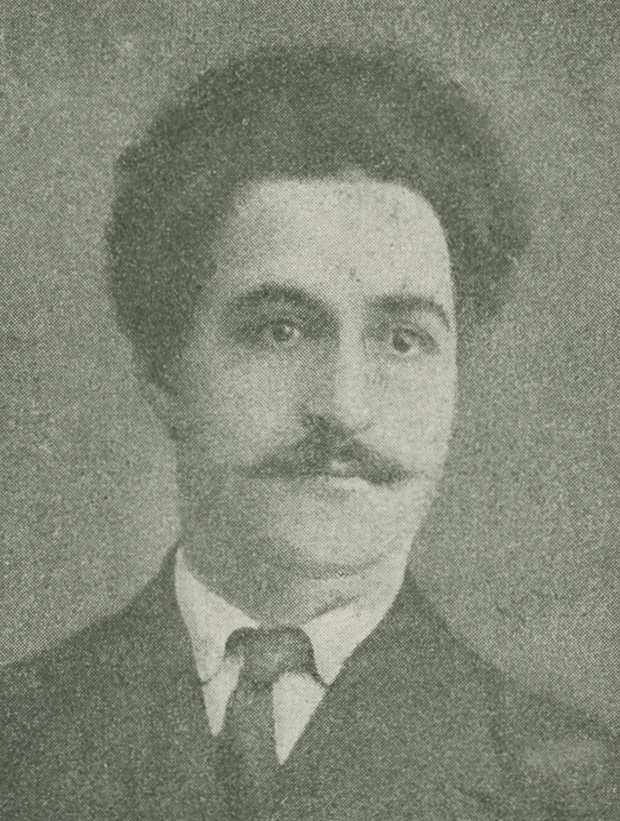

One evening Sergo Orjonikidze arrived. He had been commissioned by Comrade Stalin to visit Lenin to receive instructions. Rowing across the lake, Sergo walked through the thick brush and came out on to the glade. A short, thickset man appeared from behind a haystack and greeted him. Orjonikidze would have passed on, but the stranger tapped him on the shoulder and said:

“Comrade Sergo, don’t you recognise me?”

Clean-shaven as he then was, Lenin indeed, was unrecognizable.[2]

Sergo spent several hours with Lenin, telling him about the work of the Central Committee.

Through Orjonikidze, Vladimir Ilyich sent the Central Committee a series of instructions indicating how they should pursue their operations further.

From this hiding place Lenin steadily guided the proceedings of the Sixth Congress of the Bolshevik Party.

But even in this forest Lenin was not allowed to remain in peace. Government agents scoured the adjacent working-class district. One night Lenin was awakened by the sound of shots in his vicinity, and rifle fire echoed through the woods. “They are on my track,” thought Lenin to himself, and leaving the shack, he moved deeper into the forest. But it was a false alarm. It transpired that cadets had surrounded the Sestroretsk Works and had demanded that the workers should surrender their weapons.

At the end of July, the Central Committee of the Party decided that Lenin must be transferred to Finland. The organisation of this was entrusted to Comrade Orjonikidze, who for this purpose enlisted the services of Party members well experienced in underground work.

The plans for the removal were then drawn up. Owing to the close vigilance of the police it was no easy matter to cross the Finnish border. In [sic] was first proposed that Lenin should cross the border on foot, but a party sent out to reconnoitre discovered that passports were subjected to a strict scrutiny all along the line, so this plan had to be abandoned. It was then decided to get Lenin across the border on the engine of a local train with the assistance of Hugo Jalava, an engine-driver employed on the Finnish Railway. This suggestion, submitted to Lenin, met with his approval.

The plan of operation was as follows. Lenin with two companions were to go to Razliv Station, whence they were to proceed by train to Udelnaya, near Petrograd. There, Lenin, disguised as a fireman, was to be put on the engine of a train bound for Finland. At the last moment, however, it was decided to shorten the train journey by walking 12 kilometres to Levashovo Station. The way led through a forest and the party proceeded in single file along a narrow, barely discernible path.

Dusk set in and in the gathering darkness the party lost their way and eventually found themselves in the zone of a forest fire. Breathing was difficult owing to the acrid fumes of the burning peat. Wandering about for a long time in danger of stepping into the burning peat at almost every step, they came to a stream and, taking off their boots, waded across, knee deep in water. At last, out of the darkness, came the distant whistle of a locomotive. They pushed on and reached the station about one o’clock in the morning. A single lantern dimly lit up the platform which was thronged with armed students and cadets. Lenin hid in a roadside ditch while his companions went ahead to reconnoitre. One of them was stopped by a patrol who demanded his papers and escorted him to the station office. The raw and inexperienced guards hastened after the man thus detained, leaving the platform deserted. Just then the train came in and Lenin quickly entered the last car. He was immediately followed by his companion, Eino Rahja, a Finnish Bolshevik. The other man was released after his papers were examined.

Late at night Lenin and his companion arrived at Udelnaya Station. At no great distance the sky reflected the lights of Petrograd. They spent the night at the house of a Finnish acquaintance and next day went to the station as had been previously arranged. The train for Finland came in with driver Jalava on the footplate. Jalava took the train to a crossing some distance from the station. There Lenin mounted the engine and taking up a shovel began to work as a fireman.

At Byelo-Ostrov, the border station, the train was met by militiamen of the Provisional Government who, passing from car to car, carefully examined passports and scrutinised the passengers. The government’s sleuths were already approaching the engine and in another moment would have seized Lenin, but the engine-driver kept his head. He jumped down, quickly uncoupled the engine, and then drove off to take on water. Time passed, the second gong had already sounded, but the engine did not return. The impatient guard ran down the platform blowing his whistle. Only after the third gong did the engine come puffing into the station. Jalava hastily coupled the engine to the train and pulled out towards the Finnish border. Kerensky’s sleuths were foiled.

For some little time Lenin lived in the small Finnish village of Jalkala, 12 kilometres from Terijoki. Here, however, he had difficulty in maintaining contact with the Party Centres and it was necessary to seek a refuge for him in town. In Helsingfors a reliable hiding place was found at the house of the chief of the Workers’ Militia who acted as deputy Chief Constable, and later was himself appointed Chief Constable. Nobody suspected that this important government official would harbour the leader of the Bolsheviks.

Lenin met his host in the street and together they walked to the house. On reaching the front door Lenin looked up and down the street before entering to make sure they were not being followed. Lenin’s first request was for newspapers. He arranged to have all the Petrograd papers delivered to him daily and for the regular dispatch of his correspondence to Petrograd. As soon as he was established in his new quarters he pounced upon the fresh newspapers he found there, quickly perused them and sat down to write. The tired host fell asleep, but the scratching of the pen and the rustle of newspapers were heard for a long time in the silence of the room. On the table in front of Lenin lay a notebook bearing the title The State and Revolution. This was the book which he was then engaged in writing, and which became one of the most important documents of Bolshevism.

With great difficulty Lenin was at last provided with the necessary facilities for pursuing his work. Reliable communication was established with the Central Committee of the Party and the regular delivery of newspapers was arranged.

Amidst the trying conditions of an underground existence, and constantly hounded by spies, Lenin carefully watched the unfolding events and noted every step taken by the enemy. He at once perceived the change in the tactics of the bourgeoisie. The counter-revolution had suffered a setback in August 1917, but it had not been defeated. General Kornilov’s attempt to restore the monarchy had failed and Kornilov and his accomplices were under arrest, but they had not relinquished the idea of rebellion against the people. On the contrary, after their failure, the Kornilovites hastened to rectify their error. In August they had moved a cavalry corps against revolutionary Petrograd, but now they were mustering a much larger force. Their “prison regime” did not in the least hinder them in their counter-revolutionary activities. Kornilov and the other mutinous generals were “imprisoned” in the premises of the Girls’ High School in Bykhov and were guarded by the very same Tekinsky Regiment of the “Savage Division” which had served as Kornilov’s bodyguard at General Headquarters. Under this regime and “vigilant” guard, the counter-revolutionary Generals Kornilov, Lukomsky, Markov, Denikin, Romanovsky and the others associated with him in the recent mutiny, could quite undisturbed hatch their schemes for another mutiny.

Dispatch riders hastened one after another from Bykhov to General Headquarters—then in Moghilev—carrying the necessary information. In Bykhov, Kornilov was visited by representatives of the bourgeoisie and banking circles who promised financial assistance. On the pretext of preparing for his trial, Kornilov was allowed to summon any commander from any part of the front he desired. When these arrived they were informed of his plans for another mutiny and instructed to recruit the necessary forces. After a short period he had succeeded in mustering ten times more forces than had been at his disposal in August. He had nearly a quarter of a million men ready to hurl against the people. As was already stated in Volume One of the History of the Civil War, Kornilov’s forces included 40 special “shock battalions,” each consisting of 1,100 well armed men who had been carefully picked by their officers. These battalions were quartered at points extremely convenient for the counter-revolution, mainly on the Northern and Western Fronts. They could easily be moved forward so as to cut off the fronts from the capitals in the event of a Bolshevik insurrection there. Kornilov could also rely on the cadet schools and the officers’ training schools which could muster about 50,000 armed men loyal to the bourgeois Provisional Government. At convenient places in Finland, in the Bryansk Area, and in the Donets Basin, cavalry and Cossack divisions were held in readiness to come to the aid of the Provisional Government. An important place in Kornilov’s plan was allotted to the Czechoslovak Corps which was quartered in Right Bank Ukraine, i.e., the area on the western bank of the Dnieper. Under cover of this corps troops could be called from the South-Western and Rumanian Fronts, and the corps itself could be used against the Bolsheviks. In Byelorussia, a Polish Corps was in the course of formation under the command of General Dowbor-Musnicki, which could isolate Byelorussia from the capitals.

Naturally, at that time Lenin was not, nor could he be, aware of all these details of the plot, which came to light many years later, after the revolution had triumphed. But Lenin’s genius lay precisely in the fact that he divined the enemy’s plans and was convinced that the counter-revolutionaries were secretly and hurriedly hatching a second Kornilov plot. He realised that the bourgeoisie was preparing for civil war against the workers and peasants.

Civil war is the highest form of the class struggle, in the course of which all antagonisms are strained to the utmost and assume the form of an armed struggle. Civil war is the most acute form of the class struggle, in the course of which society splits up into two hostile camps and the question of power is settled by force of arms.

Studying the proletarian insurrection in Paris in June 1848, Marx gave the following characterisation of civil war:

“The June revolution for the first time split the whole of society into two hostile camps—East and West Paris. The unity of the February Revolution no longer exists. . . . The February fighters are now warring against each other—something that has never happened before; the former indifference has vanished, and every man capable of bearing arms is fighting on one or the other side of the barricades.”[3]

Continuing and further elaborating Marx’s doctrine, Lenin wrote the following about the nature of civil war:

“. . . experience . . . teaches us that civil war is the sharpest form of the class struggle, when a series of clashes and battles of an economic and political nature, repeating themselves, accumulating, expanding and becoming more intense, reach the stage when they become transformed into the armed struggle of one class against another.”[4]

It was this acute stage that the Russian revolution reached in September-October 1917. Society split up into two sharply antagonistic camps. One contained the bourgeoisie, the landlords and the kulak upper stratum of the rural population and of the Cossacks, and was led by the Constitutional Democratic Party in alliance with the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. This was the camp of the counter-revolution, which was feverishly preparing for civil war against the proletariat. The other camp contained the working class and the poorer strata of the peasant population, and was led by the Bolshevik Party. The bulk of the middle peasants was more and more definitely drifting towards them.

Vast changes, heralding the approach of the revolution, had taken place among the people. Primarily, the methods of struggle employed by the various classes of society had undergone a fundamental change. Lenin had repeatedly called for a historical re-examination of the question of the forms of struggle. At different periods and under different political, national, social, etc. conditions, different forms of struggle come to the forefront and become the main forms of struggle in the given period or conditions. After the Kornilov mutiny new elements appeared in the working-class movement. The industrial workers not only downed tools, not only organised economic and political strikes, but with increasing frequency drove the factory owners from their factories and took over the management themselves. This indicated that the working-class movement was being brought face to face with the question of capturing power.

Fundamental changes had also taken place in the peasant movement. The Kornilov events had proved to the masses of the peasants that the landlords were “flocking home” and were regaining possession of the land. After the Kornilov mutiny, attacks on manor houses were resumed with renewed vigour. The peasants set fire to the houses of the aristocracy, smoked out their occupants and divided the farm implements among themselves. This became the chief form of the peasants’ struggle, which was also faced with the question of capturing power. The peasant movement was growing into a peasant insurrection.

New forms of struggle developed also in the army. The soldiers refused to obey their officers. In many regiments the soldiers removed the officers they detested and elected in their places new men who were more akin to them in spirit, very often from the ranks of the soldiers themselves. In September, the sailors on some of the ships of the Baltic Fleet threw their officers overboard. The soldiers’ struggle was growing into insurrection. In the armed forces too the movement was faced with the question of capturing power.

And lastly, a notable change took place among the working people of the oppressed nations. Over the heads of their bourgeois nationalist organisations the people of these nations began more and more frequently to establish contact with the Bolshevik organisations. They began to realise that they could not obtain their freedom from the bourgeois organisations, but only from a victorious people.

Thus, the forms of struggle of all strata of the working population underwent a change. All the movements came face to face with the question of armed insurrection.

The camp of the revolution enjoyed overwhelming numerical superiority. But, as experience had proved more than once, the bourgeoisie, commanding an organised military force, a corps of officers and a network of Whiteguard organisations, was in a position to defeat the camp of the revolution. And for this purpose the Russian bourgeoisie again mustered its forces. Counter-revolution could be averted only by an armed insurrection of the workers and soldiers.

Between September 12 and 14 Lenin wrote two letters of instruction to the Central Committee, the Petrograd Committee and the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party in which he stated:

“Having obtained a majority in the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in both capitals, the Bolsheviks can and must take political power into their own hands.”[5]

With exceptional lucidity he explained why insurrection had appeared on the order of the day precisely at that moment.

“To be successful,” he wrote, “insurrection must be based not on a conspiracy, not on a party, but on the advanced class. This is the first point. Insurrection must be based on the revolutionary upsurge of the people. This is the second point. Insurrection must be based on that turning point in the history of the maturing revolution when the activity of the vanguard of the people is at its height, and when there is most vacillation in the ranks of the enemies and in the ranks of the weak, half-hearted, irresolute friends of the revolution.”[6]

These three conditions now existed.

The working class was whole-heartedly behind the Bolshevik Party. This was proved by the failure of General Kornilov’s adventure, when the workers as a whole rose in response to the call of the Bolsheviks. It was confirmed by the Soviets in both capitals when they adopted Bolshevik resolutions. It was proved also by the returns in the elections to the Soviets in the industrial centres, where the leadership of the Soviets passed into the hands of the proletarian party.

“We have behind us the majority of the class, the vanguard of the revolution, the vanguard of the people which is capable of leading the masses,” wrote Lenin.[7]

Large strata of the peasantry were freeing themselves from the influence of the landlords and the bourgeoisie. Politically, this found expression in the disintegration of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries gained in strength. The Mensheviks, searching for a new prop, clutched at the Zemstvo-ists and rural co-operators who represented the kulak groups of the rural population. The soldiers were shedding the last remnants of confidence in the compromisers.

This was proved by the growing influence of the Bolshevik Party in the armed forces. The long-suffering and starving people now realised that they could obtain peace, land and bread only from the proletariat.

“. . . we have behind us the majority of the people,” wrote Lenin.[8]

In the camp of the immediate allies of the bourgeoisie—among the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks—uncertainty and confusion prevailed; all sorts of “Left” trends arose among the Mensheviks, as well as among the Socialist-Revolutionaries.

There was vacillation also in the camp of the counter-revolution. Although the Constitutional Democrats had closely welded all the bourgeois elements in a single bloc they, nevertheless, had failed to remove the antagonisms that existed between the respective groups. The Black Hundreds were trying to drag the country back to the old regime, while the Left Constitutional Democrats still clung to the idea of a compromise with the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks.

German imperialism was the first to attempt to profit by these vacillations. Early in September 1917, the German government made secret peace overtures to France, offering concessions to France and Great Britain in the West on the understanding that Germany received her share in the East. The German diplomats hoped to make capital out of the spectre of revolution, for in the autumn of 1917 unrest broke out in the French army and the French soldiers demanded peace. The movement spread to entire army corps, and even penetrated the British forces. By raising the bogey of revolution Germany hoped to obtain peace in the West in order to have her hands free in the East to put an end to Russia.

The negotiations, however, became protracted and eventually the German manoeuvre failed. The German diplomats, never scrupulous in their methods, quickly changed front and offered to open negotiations for a separate peace with the bourgeois Provisional Government of Russia. The Provisional Government were not averse to such negotiations; they would then be free to hurl themselves with all their might upon the Bolsheviks. When, however, the news about this imperialist plot appeared in the Bolshevik newspapers, the entire bourgeois and compromising press raised an outcry against what they termed “Bolshevik slander.” The Constitutional Democratic newspapers inveighed against “the Bolsheviks’ special sources of information,” hinting that the information had come from the Germans.

Meanwhile, rumours about these backstairs negotiations appeared in the foreign press, and Entente circles began to talk about the Provisional Government’s attempt to conclude a separate peace with Germany. The Ministers of the Provisional Government, recalling that a similar attempt had once before hastened the fall of a government, and that the position of Nicholas II became very embarrassing when the news of his attempt to conclude a separate peace with Germany got abroad, made haste to cover up their tracks.

Tereshchenko, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, who only the day before had denied the “rumours” about the proposed deal, was obliged to state in the press that Germany had indeed offered to conclude peace. And after the civil war, D. R. Francis, the United States Ambassador in Russia, wrote the following:

“Tereshchenko, former Minister of Finance and Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Provisional Government came to Archangel and dined with me twice. . . .

“He furthermore assured me that about August 1, 1917, he received advantageous peace proposals from Germany; this he showed to no one in the Ministry except Kerensky.”[9]

The Russian bourgeoisie took part in this sordid conspiracy. In order to crush the revolution the propertied classes of Russia were prepared to barter part of their country.

The vacillation in the camp of the counter-revolution shackled the initiative of the bourgeoisie. In the camp of the revolution, however, under the leadership of the Bolshevik Party, forces were growing, and readiness for the struggle increased. During the Kornilov mutiny the Bolsheviks had demonstrated to the entire nation that they were capable of leading the struggle against the counter-revolution and were resolute in championing the interests of the working people.

One of Lenin’s letters to the Central Committee, the Petrograd Committee and the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party contained the following statement:

“We have before us all the objective prerequisites for a successful insurrection. We have the advantage of a situation in which only our victory in an insurrection will put an end to the most painful thing on earth, the vacillations that have sickened the people; a situation in which only our victory in an insurrection will put an end to the game of a separate peace against the revolution by openly offering a more complete, more just, more immediate peace favourable for the revolution.”[10]

Lenin summoned the Party to insurrection, but did not yet suggest a definite date for it. In his opinion, that question could be decided only by those who had direct contact with the workers and soldiers, with the masses. That the crisis had matured had to be made clear to the Party. Preparation for armed insurrection had to become the pivot of all the Party’s activities.

This, however, demanded a corresponding change in the Bolsheviks’ tactics.

First of all it was necessary to break off all connection with the so-called Democratic Conference which was to meet on September 14. Alarmed by the dimensions of the popular movement against the Kornilov mutiny, the Provisional Government made efforts to fortify its position by enlarging the base upon which it rested. With this end in view a conference was convened in Petrograd which, in order to deceive the people, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks called a “Democratic Conference.” To this Conference were invited representatives of City Dumas, the Zemstvos, the co-operative societies, and the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, army organisations, trade unions and factory committees. The City Dumas and the Zemstvos were given a far larger representation than the organisations of the workers, soldiers and peasants. The Provisional Government believed that with the representation manipulated in this way, the Democratic Conference would vote support for a bourgeois government. The compromisers thus hoped to avert a revolution and divert the country from the path of Soviet revolution to the path of bourgeois-constitutional evolution. But popular discontent with the government ran so high that even this gerrymandered conference, while voting in favour of a coalition government, opposed the inclusion of the Constitutional Democrats.

The Bolshevik Party took part in the Democratic Conference, not for the purpose of carrying on constructive work in it, as Trotsky slanderously averred, but in order to expose this manoeuvre of the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. In its resolution of September 24 on the functions of the Bolshevik group in the Preliminary Parliament—or Pre-parliament, as this Democratic Conference was also called—the Central Committee of the Party, stated:

“. . . participation in the Pre-parliament must bear merely an auxiliary character and be entirely subordinated to the task of the mass struggle.”[11]

When the tide of revolution was rising, however, and when preparations for armed insurrection were under way, even such auxiliary activities in the Democratic Conference would have been a mistake. The continued presence of the Bolsheviks at this Conference might have given the masses the impression that through the Conference peace, land and workers’ control of industry could be achieved. To remain in it would have meant creating the illusion that a peaceful development of the revolution was possible, and this would have meant diverting the masses from the revolutionary path. Lenin therefore urged that the Bolshevik group should consolidate itself, cast out the waverers and leave the Conference after making a short declaration.

“Having made this declaration,” he wrote, “having called for decisions and not talk; for action, not the writing of resolutions, we must move our entire group into the factories and barracks; its place is there; the pulse of life beats there; the source of saving the revolution is there; the driving forces of the Democratic Conference are there.”[12]

Lenin particularly emphasised that the concentration of the entire Bolshevik group in the factories and in the army barracks would facilitate the correct choice of the time at which to start the insurrection.

From participation in the Democratic Conference to boycotting the Conference—such was the change in the Party’s tactics demanded by the course that was set for insurrection.

In fact, Lenin headed his second letter to the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party “Marxism and Insurrection.” In this letter he summed up all that Marx and Engels had said about the tactics of insurrection, which the opportunists in all countries had concealed from the people for many years. The doctrine of insurrection propounded by Marx and Engels was based on the experience of the revolutions in Europe in 1848 and of the heroic Paris Commune. The great founders of Marxism studied every manifestation of revolution, learning from it and drawing fresh deductions. Lenin generalised what Marx and Engels had said on this subject and moulded their views into a harmonious system of guiding rules and propositions. In his letters and articles Lenin tirelessly stressed the point that insurrection must be regarded as an art. He insisted that having once decided on insurrection, that course must be pursued to the very end. He urged that to ensure the success of the plan it was necessary to muster the decisive forces at the decisive point and maintain superiority in morale over the enemy in the course of the insurrection. To achieve this, it was necessary, daily and hourly, to consolidate success after success, for defence meant death to armed insurrection.

Lastly, he demanded that the Bolshevik Party should treat very seriously the technical preparations for insurrection.

“And in order to treat insurrection in a Marxist way, i.e., as an art,” he wrote, “we must, at the same time, without losing a single moment, organise a staff to direct the insurrectionary forces; distribute these forces; move the loyal regiments to the most important points; surround the Alexandrinsky Theatre [where the Democratic Conference held its sessions—Ed.]; occupy the Fortress of Peter and Paul; arrest the General Staff and the government; move against the cadets and the Savage Division such detachments as will die rather than allow the enemy to reach the heart of the city; we must mobilise the armed workers, call upon them to fight the last desperate battle, occupy at once the Telegraph Offices and Telephone Exchanges, instal our staff of the insurrection in the Central Telephone Exchange and connect it by wire with all the factories, regiments, centres of armed fighting, etc.”[13]

This was not yet a plan of insurrection. As Lenin himself wrote, all these remarks were meant to illustrate how insurrection should be treated as an art. But if we compare the actual course of subsequent events with these illustrations, we shall realise how profoundly Lenin had thought out the matter of organising an insurrection, and how thoroughly he had studied the conditions for achieving victory. Lenin not only revealed and generalised Marx’s utterances but also further developed his doctrine and brilliantly applied it to the concrete conditions of our revolution.

He concluded his bold appeal to the Party by expressing firm conviction that victory would be achieved.

“Take power at once in Moscow and in Petrograd (it does not matter which begins; perhaps even Moscow may begin); we shall win absolutely and unquestionably,” he wrote.[14]

* All dates in this volume are Old Style, unless otherwise stated.—Ed.

[1] S. Y. Alliluyev, “Meetings with Lenin and Stalin.” Published in Compendium In the Days of the Great Proletarian Revolution. Episodes in the Struggle in Petrograd in 1917, History of the Civil War Publishers, 1937, p. 80.

[2] S. Orjonikidze, “Ilyich in the July Days,” in Lenin’s Last Days in Hiding, Old Bolshevik Publishers, Moscow, 1934, p. 27.

[3] K. Marx and F. Engels, “In Paris on June 23-24,” Works, Russ. ed., State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1930, Vol. VI, pp. 211-212.

[4] V. I. Lenin, “The Russian Revolution and Civil War,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 231.

[5] V. I. Lenin, “The Bolsheviks Must Assume Power,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 221.

[6] V. I. Lenin, “Marxism and Uprising,” Ibid., p. 224.

[7] Ibid., p. 226.

[8] Ibid.

[9] D. R. Francis, Russia from the American Embassy. April 1916-November 1918, Charles Scribner’s, Sons, New York, 1921, pp. 291-292.

[10] V. I. Lenin, “Marxism and Uprising,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 227.

[11] Minutes of Proceedings of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P. August 1917-February 1918, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1929, p. 81.

[12] V. I. Lenin, “Marxism and Uprising,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book I, p. 228.

[13] Ibid., p. 229.

[14] V. I. Lenin, “The Bolsheviks Must Assume Power,” Ibid., p. 223.