Lu

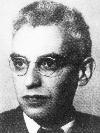

Lukács, Georg (1885-1971)

Hungarian Marxist philosopher, writer, and literary critic who influenced the mainstream of European Communist thought during the first half of the 20th century. His major contributions include the formulation of a Marxist system of aesthetics that opposed political control of artists and defended humanism and an elaboration of Marx's theory of alienation within industrial society. His What is Orthodox Marxism? and The Changing Function of Historical Materialism, demonstrated his creative and independent approach to Marxist theory.

Hungarian Marxist philosopher, writer, and literary critic who influenced the mainstream of European Communist thought during the first half of the 20th century. His major contributions include the formulation of a Marxist system of aesthetics that opposed political control of artists and defended humanism and an elaboration of Marx's theory of alienation within industrial society. His What is Orthodox Marxism? and The Changing Function of Historical Materialism, demonstrated his creative and independent approach to Marxist theory.

Born into a wealthy Jewish family, Lukács had read Marx while at school, but was more influenced by Kierkegaard and Weber. He was unimpressed with the majority of the theoretical leaders of the Second International such as Karl Kautsky, but had been impressed by Rosa Luxemburg. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution, Lukács joined the Hungarian Communist Party in 1918. After the overthrow of Béla Kun's short-lived Hungarian Communist regime in 1919, in which Lukács served as Commissar for Culture and Education, the Hungarian white terror brutally persecuted former government members.

Fleeing the White Terror, Lukacs moved to Vienna, where he remained for 10 years. He edited the review Kommunismus, which for a time became a focal point for the ultra-left currents in the Third International and and was a member of the Hungarian underground movement. In his book History and Class Consciousness (1923), he developed these ideas and laid the basis for his critical literary tenets by linking the development of form in art with the history of the class struggle. He came under sharp criticism from the Comintern, and facing expulsion from the Party and consequent exclusion from the struggle against fascism, he recanted.

Lukács was in Berlin from 1929 to 1933, save for a short period in 1930-31, at which time he attended the Marx-Engels Institute in Moscow. In 1933 he left Berlin and returned to Moscow to attend the Institute of Philosophy. He moved back to Hungary in 1945 and became a member of parliament and a professor of aesthetics and the philosophy of culture at the University of Budapest. In 1956 he was a major figure in the Hungarian uprising, serving as minister of culture during the revolt. He was arrested and deported to Romania but was allowed to return to Budapest in 1957, where, stripped of his former power and status, he devoted himself to a steady output of critical and philosophical works.

In later years, Lukács repudiated many of the positions put in his early works which had formed the starting point for such writers as Adorno and Fromm, and other tendencies which not only rejected the Stalinised version of Marxism, but departed from Marx's central principles. He frequently clashed with Jean-Paul Sartre and others who combined Marxism with psychoanalysis, structuralism and other philosophical currents inherently incompatible with Marxism.

Lukács wrote more than 30 books and hundreds of essays and lectures. Among his other works are Soul and Form (1911), a collection of essays that established his reputation as a critic; The Historical Novel (1955); and books on Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Hegel, Lenin, Marxism, and aesthetics. In his Destruction of Reason, he launched a furious attack on Heidegger's accommodation with Nazism and the whole current of irrationalism which was dominant in the pre-war years.

See Georg Lukacs Archive.

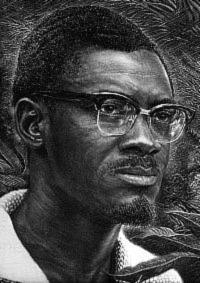

Lumumba, Patrice (1925-1961)

Lumumba was the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Lumumba was the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

He was born in Kasai province of the Belgian Congo. He was educated at a missionary school and worked in Leopoldville (Kinshasa) and Stanleyville (Kisangani) as a clerk and journalist. In 1955 Lumumba became regional president of a Congolese trade union and joined the Belgian Liberal Party. He was arrested in 1957 on charges of embezzlement and imprisoned for a year. On his release he helped found the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) in 1958. In 1959 Belgium announced a five year path to independence and in the December local elections the MNC won a convincing majority despite Lumumba being under arrest at the time. A 1960 conference in Belgium agreed to bring independence forward to June 1960 with elections in May. Lumumba and the MNC formed the first government on June 23, 1960, with Lumumba as Prime Minister and Joseph Kasavubu as President.

His rule was marked by the political disruption when the province of Katanga declared independence under Moise Tshombe in June 1960 with Belgian support. Despite the arrival of United Nations troops unrest continued and Lumumba sought Soviet aid. In September Lumumba was dismissed from government by Kasavubu, an act of dubious legality. On September 14 a coup d'etat headed by Colonel Joseph Mobutu (later Mobutu Sese Seko) and supported by Kasavubu gained power. Lumumba was arrested on December 1, 1960 by troops of Mobutu. He was captured in Port Francqui and flown to Leopoldville in handcuffs. Mobutu said Lumumba would be tried for inciting the army to rebellion and other crimes. United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold made an appeal to Kasavubu asking that Lumumba be treated according to due process of law. The USSR denounced Hammarskjold and the Western Powers as responsible for Lumumba's arrest and demanded his release.

The United Nations Security Council was called into session on December 7 to consider Soviet demands that the U.N. seek Lumumba's immediate release, the immediate restoration of Lumumba as head of the Congo government, the disarming of the forces of Mobutu, and the immediate evacuation of Belgians from the Congo. Soviet Representative Valerian Zorin refused U.S. demands that he disqualify himself as Security Council President during the debate. Secretary General Dag Hammarskj÷ld, answering Soviet attacks against his Congo operations, said that if the U.N. force were withdrawn from the Congo “I fear everything will crumble.”

Following a U.N. report that Lumumba had been mistreated by his captors, his followers threated (on December 9) to arrest all Belgians and “start cutting off the heads of some of them” unless Lumumba was released within 48 hours.

The threat to the U.N. cause was intensified by the announcement of the withdrawal of their U.N. Congo contingents by Yugoslavia, the United Arab Republic, Ceylon, Indonesia, Morocco, and Guinea. The Soviet pro-Lumumba resolution was defeated on December 14 by a vote of 8-2. On the same day, a Western resolution that would have given Hammarskjold increased powers to deal with the Congo situation was vetoed by the Soviet Union.

Lumumba was then transported on January 17, 1961 from the military prison in Thysville near Leopoldville to a “more secure” prison in Jadotville in the Katanga Province. There were reports that Lumumba and his fellow prisoners, Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, were beaten by provincial police upon their arrival in secessionist Katanga.

Two months later, Lumumba was executed along with his two aides.

In February of 2002, the Belgian government admitted to “an irrefutable portion of responsibility in the events that led to the death of Lumumba.”

In July of 2002 documents released by the United States government revealed that the CIA had played a role in Lumumba's assassination, aiding his opponents with money and political support, and in the case of Mobutu with weapons and military training. [from Wikipedia]

See Marxism and Anti-Imperialism in Africa.

Lunacharsky, Anatoly Vasilyevich (1875-1933)

Anatoly Lunacharsky was the USSR's first Commissar of Education. He was born in 1875 in Poltava (Ukraine) to minor nobility

with an educated radical consciousness. It was an environment not unlike Lenin's, though less provincial. “I became a revolutionary so early in life that I don't remember when I was not one.”

Anatoly Lunacharsky was the USSR's first Commissar of Education. He was born in 1875 in Poltava (Ukraine) to minor nobility

with an educated radical consciousness. It was an environment not unlike Lenin's, though less provincial. “I became a revolutionary so early in life that I don't remember when I was not one.”

In 1894, he left Russia for Switzerland and was a pupil of Avenarius. In 1896, he returned to Russia – and was arrested for party building activities. He was exiled to Kaluga. In 1901 or 1902, he returned to Kiev.

Isaac Deutscher wrote in a 1967 intro to this book:

“His role in the events of 1917 was quite outstanding, as all eye-witnesses testify. The 'soft' 'God-seeker' with the air of the absent-minded professor, surprised and astonished all who saw him by his indominable militancy and energy. He was the great orator of Red Petrograd, second only to Trotsky, addressing every day, or even several times a day, huge, hungry and angry crowds or workers, soldiers and saliors....”

He was jailed by Kerensky in July 1917. Made Commissar of Education in Lenin's first Soviet government. Died in 1933, just before taking the station of Ambassador to Spain.

See the Lunacharsky Internet Archive

Lupus

Nickname for Marx and Engels' friend Wilhelm Wolff

Luria, Alexander Romanovich (1902-1977)

Alexander Romanovich Luria (1902-1977) was born in Kazan, an old Russian university city east of Moscow. He entered Kazan University at the age of 16 and obtained his degree in 1921 at the age of 19. While still a student, he established the Kazan Psychoanalytic Association and planned on a career in psychology. His earliest research sought to establish objective methods of assessing Freudian ideas about abnormalities of thought and the effects of fatigue on mental processes.

Alexander Romanovich Luria (1902-1977) was born in Kazan, an old Russian university city east of Moscow. He entered Kazan University at the age of 16 and obtained his degree in 1921 at the age of 19. While still a student, he established the Kazan Psychoanalytic Association and planned on a career in psychology. His earliest research sought to establish objective methods of assessing Freudian ideas about abnormalities of thought and the effects of fatigue on mental processes.

In the early 1930s Alexander Luria undertook a pioneering study in Soviet Central Asia to grasp the historical transformation of human psychological functions under the influence of changing psychological tools. Luria (1976) showed that implementation of written language and logico-mathematical operations, typically connected to formal schooling, had significant influence on how people categorized objects of the environment.

Luria made advances in many areas, including cognitive psychology, the processes of learning and forgetting, and mental retardation. One of Luria’s most important studies charted the way in which damage to specific areas of the brain affect behavior. Today, Luria is honored as the father of neuropsychology.

After writing several books in the 1970’s, Alexander Luria died of heart failure at the age of 75. Alexander Romanovich Luria autobiography, The Making of Mind, was published in 1979 which outlines his most important contributions to developing a Cultural-Historical Psychology.

Works By A. R. Luria:

Luria, A. R. (1932). The Nature of Human Conflicts. New York: Liveright.

Luria, A. R. and F. A. Yudovich. (1959). Speech and the Development of Mental Processes. London: Staples Press.

Luria, A. R. (1960). The Role of Speech in the Regulation of Normal and Abnormal Behavior. New York: Irvington.

Luria, A. R. (1966). Higher Cortical Functions in Man. New York: Basic Books.

Luria, A. R. (1970). Traumatic Aphasia: Its Syndromes, Psychology, and Treatment. The Hague: Mouton.

Luria, A. R. (1968). The Mind of Mnemonist. New York: Basic Books.

Luria, A. R. (1972). The Man with a Shattered World. New York: Basic Books.

Luria, A. R. (1973). The Working Brain. New York: Basic Books.

Luria, A. R. (1979). The Making of Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

See the Alexander Luria Archive.

Luxemburg, Rosa (1871-1919)

Born on March 5th, 1871 in Zamoshc of Congress Poland, Rosa Luxemburg was born into a Jewish family, the youngest of five children. In 1889, at 18 years old, Luxemburg's revolutionary agitation forced her to move to Zürich, Switzerland, to escape imprisonment. While in Zürich, Luxemburg continued her revolutionary activities from abroad, while studying political economy and law; receiving her doctorate in 1898. She met with many Russian Social Democrats (at a time before the R.S.D.L.P. split); among them the leading members of the party: Georgy Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod. It was not long before Luxemburg voiced sharp theoretical differences with the Russian party, primarily over the issue of Polish self-determination: Luxemburg believed that self-determination weakened the international Socialist movement, and helped only the bourgeoisie to strengthen their rule over newly independent nations. Luxemburg split with both the Russian and Polish Socialist Party over this issue, who believed in the rights of Russian national minorities to self-determination. In opposition, Luxemburg helped create the Polish Social Democratic Party.

Born on March 5th, 1871 in Zamoshc of Congress Poland, Rosa Luxemburg was born into a Jewish family, the youngest of five children. In 1889, at 18 years old, Luxemburg's revolutionary agitation forced her to move to Zürich, Switzerland, to escape imprisonment. While in Zürich, Luxemburg continued her revolutionary activities from abroad, while studying political economy and law; receiving her doctorate in 1898. She met with many Russian Social Democrats (at a time before the R.S.D.L.P. split); among them the leading members of the party: Georgy Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod. It was not long before Luxemburg voiced sharp theoretical differences with the Russian party, primarily over the issue of Polish self-determination: Luxemburg believed that self-determination weakened the international Socialist movement, and helped only the bourgeoisie to strengthen their rule over newly independent nations. Luxemburg split with both the Russian and Polish Socialist Party over this issue, who believed in the rights of Russian national minorities to self-determination. In opposition, Luxemburg helped create the Polish Social Democratic Party.

During this time Luxemburg met her life-long companion Leo Jogiches, who was head of the Polish Socialist Party. While Luxemburg was the speaker and theoretician of the party, Jogiches complimented her as the organiser of the party. The two developed an intense personal and political relationship throughout the rest of their lives.

Luxemburg left Zürich for Berlin in 1898, and joined the German Social Democractic Labour Party. Quickly after joining the party, Luxemburg's most vibrant revolutionary agitation and writings began to form. Expressing the central issues of debate in the German Social Democracy at the time, she wrote Reform or Revolution in 1900; against Eduard Bernstein's revisionism of Marxist theory. Luxemburg explained:

"His theory tends to counsel us to renounce the social transformation, the final goal of Social-Democracy and, inversely, to make of social reforms, the means of the class struggle, its aim. Bernstein himself has very clearly and characteristically formulated this viewpoint when he wrote: "The Final goal, no matter what it is, is nothing; the movement is everything."

While Luxemburg supported reformist activity (as the means of class struggle), the aim of these reforms was a complete revolution. She stressed that endless reforms would continually support the ruling bourgeois, long past the time a proletarian revolution could have begun to build a Socialist society. Luxemburg, along with Karl Kautsky, helped to prevent this revisionism of Marxist theory in the German Socialist party. (Further Reading: 1904: Social Democracy and Parliamentarism)

By the 1905 Revolution in Russia, Luxemburg refocused her attention to the Socialist movement in the Russian Empire, explaining the great movement the Russian proletariat had begun:

"For on this day the Russian proletariat burst on the political stage as a class for the first time; for the first time the only power which historically is qualified and able to cast Tsarism into the dustbin and to raise the banner of civilization in Russia and everywhere has appeared on the scene of action."

Luxemburg stood by the Marxist theory of the Russian proletariat leading a Socialist revolution; in opposition to the Russian Menshevik and Socialist-Revolutionary parties, but in support of the Bolshevik party. Luxemburg moved to Warsaw to aid the Russian revolutionary uprising, and was imprisoned for her activities.

In 1906, Luxemburg began to strongly advocate her theory of The Mass Strike as the most important revolutionary weapon of the proletariat. This continual drive became a major point of contention in the German Social Democratic party, primarily opposed by August Bebel and Karl Kautsky. For such passionate and relentless agitation, Luxemburg earned the nickname "Bloody Rosa."

Before the first World War, Luxemburg wrote The Accumulation of Capital in 1913; a work explaining the capitalist movement towards imperialism. With the begining of World War I, Luxemburg stood ardently against the German Social-Democratic Parties' social-chauvinistic stand; supporting German aggression and annexations of other nations. Allied with Karl Liebknecht, Luxemburg left the Social Democractic party, and helped form the Internationale Group, which soon became the Spartacus League, in opposition of Socialist national chauvinism, agitating instead that German soldiers turn their weapons against their own government and overthrow it.

For this revolutionary agitation, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were arrested and imprisoned. While in prison, Luxemburg wrote the Junius Pamphlet, which became the theoretical foundation of the Spartacus League. Also while in prison, Luxemburg wrote on the Russian Revolution, most famously in her book: The Russian Revolution, where she warns of the dictatorial powers of the Bolshevik party. Here Luxemburg explains her views on the theory of the dictatorship of the proletariat:

"Yes, dictatorship! But this dictatorship consists in the manner of applying democracy, not in its elimination, but in energetic, resolute attacks upon the well-entrenched rights and economic relationships of bourgeois society, without which a socialist transformation cannot be accomplished. But this dictatorship must be the work of the class and not of a little leading minority in the name of the class -- that is, it must proceed step by step out of the active participation of the masses; it must be under their direct influence, subjected to the control of complete public activity; it must arise out of the growing political training of the mass of the people.

While Luxemburg attacked the Soviet government being dominated by the strong hand of the Bolshevik party, she recognised the Civil War that was raging through Russia and the present need for such a government:

"It would be demanding something superhuman from Lenin and his comrades if we should expect of them that under such circumstances they should conjure forth the finest democracy, the most exemplary dictatorship of the proletariat and a flourishing socialist economy. By their determined revolutionary stand, their exemplary strength in action, and their unbreakable loyalty to international socialism, they have contributed whatever could possibly be contributed under such devilishly hard conditions. The danger begins only when they make a virtue of necessity and want to freeze into a complete theoretical system all the tactics forced upon them by these fatal circumstances, and want to recommend them to the international proletariat as a model of socialist tactics."

Luxemburg later opposed the newly formed Soviet government's efforts to come to Peace on all fronts, by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany. (Further reading: The Russian Tragedy)

In November, 1918, the German government reluctantly released Luxemburg from prision, whereupon she immediately began again revolutionary agitation. A month later, Luxemburg and Liebknecht founded the German Communist Party, while armed conflicts were raging in the streets of Berlin in support of the Spartacus League.

On January 15, 1919, Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, and Wilhelm Pieck; the leaders of the German Communist Party, were arrested and taken in for questioning at the Adlon Hotel in Berlin. While what happened is not known, save for the last sentence, one account is that they were told they were to be relocated; German soldiers escorted Luxemburg and Liebknecht out of the building, knocking them unconscious as they left. Pieck managed to escape, while the unconscious bodies of Luxemburg and Liebknecht were quietly driven away in a German military jeep. They were shot, and thrown into a river.

With the finest leaders of the German Communist movement murdered, the gates of rising German facism opened unhindered.

Further Reading: Rosa Luxemburg Internet Archive

Off-site link: ‘If You Do Not Follow the Order You Will Be Shot’: New facts about the murder of Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg

Lu Xun (Lu Hsun) (1881-1936)

Lu Xun (Lu Hsun) was the pen name of Zhou Shuren. Lu is widely regarded as one of modern China’s most prominent and influential writers. His work frequently promoted radical change through criticism of antiquated cultural values and repressive social customs.

Lu Xun (Lu Hsun) was the pen name of Zhou Shuren. Lu is widely regarded as one of modern China’s most prominent and influential writers. His work frequently promoted radical change through criticism of antiquated cultural values and repressive social customs.

Zhou was born into a poor family. His father was unable to provide for the family and he died during Zhou’s teenage years. Zhou’s mother was well-educated and she encouraged in his studies. Zhou demonstrated a keen intellect early in life. He studied at the Jiangnan Naval Academy, the School of Railways and Mines in Nanjing and the Medical College at Sendai in Japan. During the course of his studies, he became acquainted with social movements aimed at reforming and reshaping Chinese society.

During the course of Zhou’s political and intellectual development, he concluded that a “literary movement” was needed to build awareness and incite action amongst the oppressed. As early as 1906, he decided to publish a literary magazine, but his early attempts at organizing such an endeavor were unsuccessful. In 1908, he joined the anti-Qing revolutionary party, Guang Fu Hui, and he remained involved with this group up to the Revolution of 1911 which resulted in the removal of the Qing Dynasty. Zhou was ultimately disenchanted with the results of the Revolution, for although the Qing Dynasty was unseated, the people of China languished amidst imperialist intervention and oppressive semi-colonial conditions.

Zhou Shuren struggled with uncertainty as to how he could best utilize his political awareness while he immersed himself in the study of Chinese culture. He adopted the pen name of “Lu Xun,” partially in tribute to his mother, whose surname was Lu. With some encouragement from peers, Lu ultimately wrote and published his first story, “A Madman’s Diary,” in 1918. The story was published in the May Fourth movement’s magazine “New Youth” Lu’s work was well received and he followed up with a number of other short stories, including his celebrated tale of the Revolution of 1911, “The True Story of Ah-Q.” In 1923, Lu published “A Call to Arms,” which was an anthology of his most acclaimed works.

Lu Xun quickly gained notoriety as a stirring, insightful, and prolific writer. In addition to writing, Lu worked as an editor, professor and dean of studies. Lu began studying Marxism-Leninism in 1928 and shortly thereafter, he undertook the translation of works concerning Marxist literary theory. Although Lu never joined the Chinese Communist Party, he was widely regarded as a Marxist in the later years of his life and he worked closely with communists in many anti-imperialist and anti-fascist campaigns. Lu advocated a united front by the CCP and the Kuomintang against the forces of Japanese imperialism. While afflicted with tuberculosis, Lu continued to write passionately about the struggle against Japanese aggression until his death in 1936.

Further Reading: Lu Xun Archive