Next to the Northern, the most important front for the successful accomplishment of the proletarian revolution was the Western Front. The latter was the nearest front to Moscow and, with the exception of the Northern Front, the nearest to Petrograd. In the rear of the Western Front was that hotbed of the militarist counter-revolution, General Headquarters of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief. The trenches of the Western Front stretched from Dvinsk to Pinsk. Its headquarters were situated in Minsk. As in the case of the Northern Front, three armies were disposed here: the Third, the Tenth and the Second.

The Second Army occupied the extreme left flank of the Western Front—the Pinsk marshes. It had its headquarters at Slutsk, but its most vital centre was Nesvizh, situated closer to the trenches. The Committee of the Second Army also had its headquarters in that town. On October 26, the Bolshevik group of the Army Committee received news of the insurrection in Petrograd and forthwith called upon the Committee to recognise the new government. The Committee, two-thirds of whose members were compromisers, declined. The Bolsheviks thereupon resigned. Many of them hastened to different parts of the front to rouse the soldiers in the trenches for the struggle in support of the Soviet Government, while those who remained in Nesvizh, assisted by comrades who had arrived from Minsk, developed the activities of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

Already before the October events had begun the Bolsheviks had summoned to Nesvizh the 32nd Siberian Regiment to offset the 2nd Urals Cossack Division which was then quartered in the town. On October 26 the Siberian Regiment was already close to the town. The Bolshevik members of the Army Committee launched a campaign among the units of the Second Army in favour of electing new Divisional and Corps Committees, of electing delegates to the Army Congress which was to meet on November 1, of establishing control over the staffs and telegraph, and also of seizing the corps newspapers. In most of the regiments, the Regimental Committees were already Bolshevik, the exceptions being several regiments of the 9th and 3rd Siberian Corps. In the former, Ukrainian nationalist influence, and in the latter, Socialist-Revolutionary influence, was strong. But command over the regiments was captured very quickly; the officers proved to be so isolated that they could offer no resistance. The temper of most of the units in the Second Army can be judged by the resolution that was adopted on October 27 at the joint meeting of Regimental, Company and Command Committees of the 18th Karsky Grenadier Regiment, which read as follows:

“Only recently we experienced the Kornilov adventure, and now that traitor Kerensky is again advancing on Petrograd to suppress freedom and to drench the city with the blood of the proletariat who are dying in battle in the streets. The Karsky Regiment declares—and let the traitors and butchers know this—that we are ready to lay down our lives for the workers and peasants. We stand for the transfer of power to the Soviets, for peace and for land. Long live the Military Revolutionary Committee!”[1]

The spirit among the Grenadiers was particularly revolutionary. In the two divisions of the Grenadier Corps, which occupied the trenches near Nesvizh, the Bolsheviks had conducted a vigorous campaign in favour of new elections of the Divisional Committees. On their own accord they fixed the date on which the Second Congress of the Division was to be held, viz., October 28. At first the Divisional Committee tried to ignore the demand for the convocation of the Congress, but when it saw that the delegates were assembling in spite of it, it yielded to the fait accompli.

Two hundred and fifty delegates arrived for the Congress. The day of the opening was raw and cold. Rain and sleet fell all day, turning the ground into a veritable quagmire. The Congress was held in the Divisional Staff dining room, which was nothing more than a large, dilapidated barn. The tables were arranged round the walls to serve as the delegates’ benches. Having no place in which to hold their group meeting, the Bolsheviks limited themselves to ascertaining the party affiliation of the delegates. This was done in the following way: before the Congress was opened the Bolshevik delegates and their sympathisers were requested to go to the left side of the shed and all the rest to the right. The overwhelming majority of the delegates lined up on the left; on the other side there was a handful of men, headed by the members of the old committees.

The entire Congress took the stand of the Bolsheviks. Almost without debate it adopted a resolution expressing no confidence in the compromisers, supporting the Soviet Government and demanding new elections of the committees. This Bolshevik resolution polled 210 votes, the resolution moved by the Socialist-Revolutionaries polled only 35. The crestfallen compromisers thereupon resorted to demagogy. They got up and demanded that the Bolsheviks should “say here and now, quite openly, whether they can guarantee that peace will be concluded with the Germans tomorrow.”[2] Before the Bolsheviks could reply, a private of the 5th Kiev Regiment, nonparty, rose from the back benches and expressed himself in the following plain, but vivid and convincing terms:

“You must not think that the Bolsheviks will take from their pockets and put before us right here peace, bread and land, as easily as taking a pipeful of tobacco from a pouch. No, we shall have to fight for peace and land. And we shall fight for these side by side with the Bolsheviks.”[3]

The Socialist-Revolutionaries refused to participate in the election of the new Divisional Committee on the grounds that it was “impossible to work jointly with the Bolsheviks.” As a result, only Bolsheviks and their sympathisers were elected. The Congress decided to recall the old representatives of the division from the Corps Committee and to send new representatives, Bolsheviks, in their place.

The 1st Grenadier Division also accepted the lead of the Bolsheviks. A general meeting of its Regimental and Brigade Committees held on October 27 discussed the question of convening an Army Congress and resolved that:

“Being of the opinion that the activities of the Army Committee are out of harmony with the will and demands of the masses . . . we demand the dismissal of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik Social-Democratic members. The Bolshevik group is to act as the Revolutionary Committee of the Second Army pending the convocation of the Army Congress. . . . We shall back our demands by armed force. . . . We shall obey only the orders that are sanctioned by the group to which we entrust our forces. We shall place ourselves at its disposal at the first word of command.”[4]

After the Divisional Congresses, a Congress of the whole Grenadier Corps was called. Straight from the Divisional Congresses, late at night, the Bolshevik delegates of the 2nd Division walked to Corps Headquarters, a distance of about eight kilometres.

During the morning of October 29 the delegates busied themselves with the preparations for the Congress. They took possession of the small corps printing plant, where the Izvestia of the Executive Committee of the Grenadier Corps was printed, and one of the delegates, a compositor by trade, took his place at the type case. The printing of the compromising Izvestia was stopped at once and Bolshevik leaflets were set up and printed instead.

The opening of the Congress was fixed for the next day, October 30, as the arrival of several more delegates was expected. Meeting in small groups, the delegates engaged in a lively discussion of the questions that were to come up on the morrow. Suddenly, at about 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the hum of voices in controversy was interrupted by the sharp ringing of the telephone. This was a call from the Staff of the 2nd Grenadier Division. Somebody reported in an excited voice that the Germans had suddenly started an offensive on the sector occupied by the division.

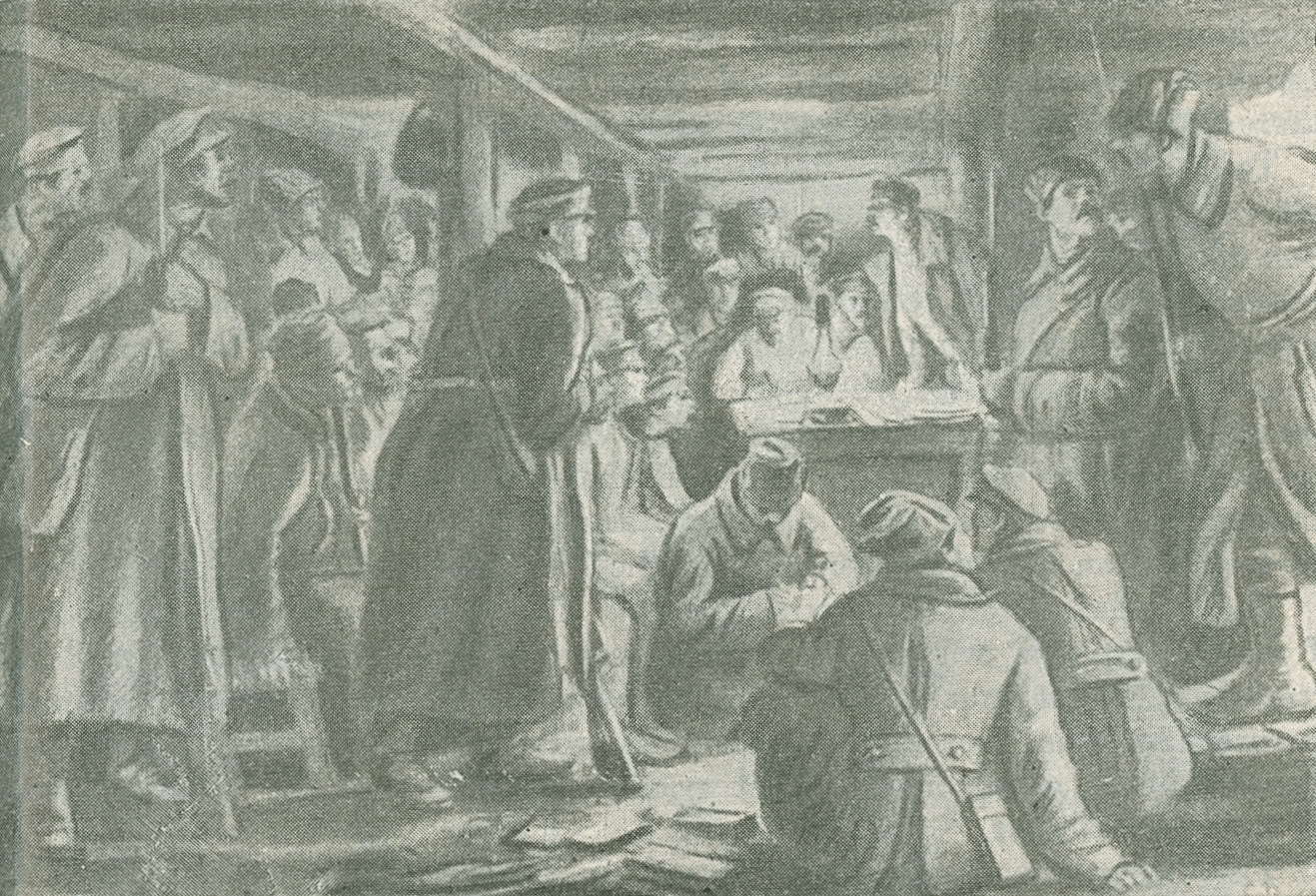

Taking advantage of a favourable wind the Germans started a gas attack and in the course of an hour released three gas waves. The wind veered soon after, however, and dispersed the gas. At 4 p.m. a heavy artillery duel commenced, in which it was roughly estimated 150 guns on each side were engaged. Shells screamed continuously and the guns roared in the immediate vicinity of the premises where the delegates to the Congress were gathered. German shells burst and emitted clouds of asphyxiating gas. Round about 5 p.m. Corps Headquarters reported that the Germans had launched an attack under cover of their artillery, and that their infantry had rushed the trenches on the sector occupied by the 7th Taurida Grenadier Regiment.

The delegates were filled with anxiety. The suspicion arose in the minds of many that this was an act of treachery and that the Generals and the Provisional Government had come to an arrangement with the Germans to surrender this sector of the front in order to suppress the revolution. The Bolshevik group held a meeting and decided that the Congress must be held at all cost.

The Congress was opened at 5 p.m. in a large dugout which served as the staff clubroom. The necessary precautionary measures were taken. The tables were piled with gas masks, and buckets of water were handy. At the entrance to the dugout straw was piled for bonfires. The artillery kept pounding away without interruption. The fields echoed with the roar of guns and the thick beams of the dugout shook with the impact of the detonations. But the meeting proceeded in a calm and organised manner.

The Congress was opened by the Chairman of the Corps Committee who, immediately on declaring the Congress open announced his resignation and vanished. The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, however, would not surrender their positions. On the plea that “the situation at the front was critical” and in an endeavour to intimidate the delegates by stressing the danger created by the German offensive, they proposed that a united Corps Committee be formed “on a parity basis.” The Congress emphatically rejected this proposal. In the resolution it adopted it heartily welcomed the revolution that had been accomplished in Petrograd and declared its readiness to rise in defence of the Soviet Government at any moment. The Congress elected a delegate to go to Petrograd to convey greetings to the leader of the proletarian revolution, Lenin. The newly elected Bolshevik Corps Committee immediately took over the command of the corps, occupied the radio station, and set up control over the Staff.

Soon after the delegates had dispersed the artillery fire subsided. Evidently, the Germans had calculated that the revolution in Petrograd had shaken and weakened the front and had attempted to take advantage of this. Their attack, however, encountered determined resistance. The fighting became very fierce and drew to a close only at night. The Grenadiers who put up a stubborn defence, lost as many as 1,500 men in killed and wounded, but they repulsed all the Germans’ attacks. Remarkable coolness, fighting efficiency and determination were displayed precisely by those regiments which had been the first to go over to the Bolshevik revolution. This was admitted even in the confidential report of the generals wherein it was stated:

“On October 30 it was revealed that the staunchness and fighting spirit of the units, after all, enables them to put up a stubborn defence of their positions and to deliver sharp, local blows. The fighting on October 30 even roused a certain amount of enthusiasm and elation among the majority of the men.”[5]

How many reams of paper had been used up to prove that the Bolsheviks had disintegrated the army and were responsible for the soldiers’ wholesale desertion of the front! The Constitutional Democrats had heaped slander on the Bolsheviks; the Socialist-Revolutionaries had poured obscene abuse upon them; and the Mensheviks, foaming at the mouth, had made scurrilous charges against them. This was a repetition of what had occurred near Riga in August 1917. For months the Constitutional Democrats, Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries had been conducting a campaign of calumny against Okopnaya Pravda and Okopny Nabat, the Bolshevik newspapers for soldiers published in Riga. They accused the Bolsheviks of being paid agents of the Germans, of inciting the men to desert, to commit treason, and what not. But when Riga had to be defended against the Germans it was precisely the Bolshevik regiments, which had been imbued with the ideas propagated by Okopnaya Pravda and Okopny Nabat that distinguished themselves by their bravery. This could not be hushed up. All the newspapers, except the Socialist-Revolutionary Dyelo Naroda, published the report of the Secretary of the Ministry for War, Savinkov—one of the Socialist-Revolutionary leaders and a bitter enemy of the Bolsheviks—in which he referred to the firmness and courage displayed by the Bolshevik regiments which had defended Riga. In this report Savinkov said:

“There were [near Riga—Ed.] . . . Bolshevik regiments which fought with exceptional courage and lost as much as three-fourths of their effectives, whereas other regiments failed to withstand the slightest enemy assault.”[6]

The Germans had hurled their best forces into the attack on Riga. The units of the Northern Front were obliged to withstand a heavy blow. Entire divisions perished. The notorious Voitinsky, the Assistant Commissar of the Northern Front, was compelled to state in the press that the soldiers were fighting staunchly, suffering heavy casualties, but holding up the enemy’s advance.[7] The Lettish Rifles fought with exceptional heroism at Riga. Exhausted though they were, they charged again and again.

Not only Voitinsky, but other Commissars of the Provisional Government on various fronts also felt obliged publicly to refute in the press the slanders of the bourgeois newspapers. Thus, Lunchinsky, the Assistant Commissar of one of the armies on the Rumanian Front, published a statement to the effect that the newspapers were printing garbled reports about the retreat of the Russian forces in the region of Novoselitsa and making it appear that this was a deliberate opening of the front. Like Voitinsky, Lunchinsky was obliged to admit that the enemy’s offensive, launched with numerically superior forces after heavy artillery preparation, had been checked. In spite of the fact that the enemy was firing gas shells, the men rushed to counter-attack, displaying great valour and heroism.[8] And these were the regiments in which Bolshevik influence was strong. The same thing happened on other fronts that August, long before the October Revolution.

But in October the Bolsheviks came into power; the defenders of the bourgeoisie were driven from the army. The soldiers were given a clear and definite idea of the aims of the struggle. And the soldiers who but yesterday had refused to take part in the offensive in the interests of the bourgeoisie, were today fighting and dying for the Soviet regime. The transfer of power to the people stimulated the fighting spirit of the soldiers and inspired them to fight for the Soviet motherland they had newly acquired.

The masses of the people, and the army and the navy, rightly regarded the victory of the Great October Socialist Revolution as a guarantee against the utter defeat of the country by German imperialism. The undisguised treason of the Russian capitalists and landlords who had committed one treacherous deed after another, who had surrendered Riga, Esel and Dago, and who were obviously ready to surrender Petrograd to the Germans as long as the revolution was suppressed, opened everybody’s eyes. The masses of the people regarded the Bolsheviks as the only force capable of organising the defence of the country and of bringing the war to a close. Lenin’s dictum: “From October 25 onwards we are Defencists,” expressed the sentiments of the entire people which was mustering its forces for the purpose of defending the land and liberty it had won as a result of the proletarian revolution. The countless published and unpublished resolutions passed by military units on all fronts, in all armies, corps, and divisions, confirmed the fact that the army and the navy, which had been betrayed by the Kornilov generals, were ready to defend their country now that it was free. There was not a case before the victory of the October Socialist Revolution, and particularly after it, of any military unit failing to perform its duty. More than that, the army tried to retain that part of the commanding personnel which was still capable of fighting sincerely in defence of the country. The Soviet Government did all in its power to facilitate this.

One of the first measures taken by the Soviet Government was to build up a strong army administration. For this purpose it was decided to utilise the services of the military experts, even of the highest rank, but only on condition that these ex-officers worked honestly and sincerely to defend the country. Thus, two days after the arrest of the Provisional Government, General Manikovsky, the Minister for War and Admiral Verderevsky, Minister for the Navy in the last Provisional Government, were released from the Fortress of Peter and Paul, and both were offered work on national defence. General Manikovsky accepted a post in the War Department and subsequently served in the Red Army. On October 30, the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet ordered all staff officers of the Petrograd Military Area and officials of the Ministry for War and Ministry for the Navy immediately to resume their duties.[9] On October 27, the 10th Special Regiment of the Petrograd garrison passed a resolution welcoming the victory of the revolution and the inauguration of the Soviet regime.

“Only such a regime,” stated the resolution, “in which there is no internal discord and which trusts the people (democracy) is capable of extricating the country from economic chaos and of defeating German imperialism.”[10]

The soldiers realised that the spearhead of the October Socialist Revolution was directed against Russian and German imperialism. They fought the Russian bourgeoisie which had driven them into an unjust war, and the German militarists, whom they had been fighting for three and a half years.

Even while the struggle for the victory of the proletarian revolution was still proceeding the soldiers felt instinctively that the Russian bourgeoisie were secretly negotiating with the German imperialists, who feared the revolution of the masses of the people of Russia no less than the Russian imperialists. After the victory of the revolution these apprehensions concerning the likelihood of a deal between the Russian and German imperialists grew. An imperialist attack on the young Soviet Republic was to be expected primarily from Germany. Consequently, the masses of the soldiers at the front demanded not only peace, but also the preservation of the vitality and fighting efficiency of the army, so that it might be in a position to deal with any attack that was made on Soviet Russia.

Thus, the first order issued by the newly formed Military Revolutionary Committee of the Second Army called upon all departments and the entire commanding personnel to continue to perform their respective functions. The Revolutionary Committee took all the measures in its power to prevent the normal life of the army from being disturbed and its fighting efficiency impaired.[11] Shortly afterwards, the Congress of the Second Army made a declaration in which it reaffirmed that military operations and army administration in the different units were to be conducted by the existing bodies, under the control of the Commissars of the Army Military Revolutionary Committee.[12] When negotiations for an armistice were opened with the Germans, the Soviet Government, in an order issued to the army and navy, stated:

“Stand firm in these last days. Exert all efforts and hold the front in spite of privation and hunger. Success depends upon your revolutionary staunchness.”[13]

The bulk of the army and navy was well aware that until peace was concluded it was necessary to stand fast, arms in hand, prepared for all contingencies.

In the 9th and 50th Corps of the Second Army, the Bolsheviks won power as quickly as in the Grenadier Corps. A slight hitch occurred only in the 5th Division of the 9th Corps, where the Ukrainian Nationalists tried to place obstacles in the way of the Bolsheviks.

On October 27 and 28 the Congress of the 3rd Siberian Corps was held. The delegates to this Congress had been elected before the October events. At the Congress the vote was equally divided between the Bolsheviks and the compromisers. The Congress elected a Corps Committee on a “parity basis,” but this body proved utterly inefficient, and the Bolsheviks were obliged to dissolve it. In this corps, too, actual power passed into the hands of the Bolsheviks.

On October 31, the Bolshevik delegates who had been elected by the men for the Army Congress began to assemble in Nesvizh. The compromising Army Committee tried to prevent the Congress from meeting, but neither the Committee, nor the Commissar, nor the Commander-in-Chief of the Army possessed effective forces to do this. The Congress which opened on November 1 in the castle of Prince Radzivil, elected a Military Revolutionary Committee for the Second Army and issued a special declaration concerning the introduction of revolutionary law in the army.

By this declaration all power in the army was vested in the executive organ of the Congress—the Army Committee. Counter-revolutionary activities were to be stopped by the immediate dismissal and arrest of the culprits. All those who openly refused to recognise the new government were liable to arrest. The Commissar of the Provisional Government was dismissed and the “Committee for the Salvation” on this front was proclaimed treasonable to the country and the revolution and its members subject to arrest. All the Unit Committees were granted the right to nominate candidates for the post of commanders, which nominations were to be endorsed by the higher committees. Political leadership, cultural and educational activities and questions concerning the utilisation of the armed forces for all sorts of civil functions were proclaimed to be matters with which only the committees were competent to deal.

That is how the October Revolution was accomplished in the Second Army, which greatly augmented the Bolshevik forces.

The Tenth Army occupied the centre of the Western Front and had its headquarters in the small town of Molodechno. The manner in which the news of the insurrection in Petrograd was received in this army was described in Pravda of November 4, 1917, by the delegates of the 107th Troitsky Regiment, as follows:

“The news of the revolution arrived on October 26. It was welcomed with enthusiasm and loud cheers. A meeting of the entire regiment was held and a resolution was passed pledging the new government full support. . . . On the 27th, another telegram arrived announcing the capture of Petrograd by Kerensky, urging that no confidence be placed in the Military Revolutionary Committee, and also announcing the arrest of the Bolsheviks. But nobody believed this telegram.”[14]

Several days previously, the 107th Troitsky Regiment had passed a resolution calling for the transfer of power to the Soviets. Delegates of this regiment visited a number of other regiments in this division such as the 105th, 106th and 108th, and canvassed support for this resolution. Everywhere the soldiers unanimously expressed their agreement with it. Even in the shock battalion the overwhelming majority of the soldiers supported the resolution, only a small handful protesting and demanding the arrest of the delegates.

A copy of the resolution was sent to the Committee of the 27th Division in order that the delegate from the division might convey it to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets. At first the Divisional Committee refused to accept the resolution, but when the delegates threatened to take it to the Congress themselves, they pretended to yield. They accepted the copy of the resolution, but failed to send it to the Congress.

Such was the situation on the eve of the October Revolution not only in the 27th Division but also in the other units of the Tenth Army. By that time the rupture between the masses of the soldiers and the compromising Unit Committees was complete.

On receiving the news of the insurrection in Petrograd, the Army Committee of the Tenth Army, jointly with the Government Commissar issued a manifesto to the troops prophesying the doom of the revolution. On October 28, a conference of representatives of Regimental, Divisional and Corps Committees, or rather, of the higher officials of these committees, most of whom were compromisers, was held in Molodechno. But even at a conference of this description about fifty delegates voted in favour of the Bolsheviks. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks mustered about 100 votes. A small group of representatives took up a “neutral” position and on all questions abstained from voting.

The conference was a stormy one. The Bolsheviks demanded unqualified recognition of the Soviet regime and of the government set up by the Second Congress of Soviets. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks denounced the insurrection and proposed that the Petrograd “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and Revolution” be recognised as the source of power and that it should be entrusted with the task of forming a government. The Bolsheviks refused to be represented on the Conciliation Committee that was appointed to draft the resolution and left the conference. After that, the compromisers passed their resolution and elected to the Army Committee another fourteen of their supporters from among the delegates. The conference instructed this Army Committee to set up a “Committee for the Salvation of Freedom and the Revolution” and “to establish close contact with the analogous committee of the Western Front.”

But nothing could check the progress of revolutionary events in the Tenth Army. In a confidential report on the Western Front we read:

“On October 29, the Committee of the Staff of the 2nd Siberian Rifle Division established control over the Staff’s telephone and telegraph offices. Telegrams signed by Commissars and the Committee were destroyed. The divisional commander and the commandant of the Staff were arrested, but soon after released.”[15]

In the regiments and divisions events developed at a rapid pace. On November 7, the Third Congress of the Tenth Army was opened in Molodechno, attended by 600 delegates, of whom nearly two-thirds supported the Bolsheviks. During the election of the Presidium, 326 votes were cast for the Bolshevik ticket and 183 votes for the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik ticket; eight Bolsheviks and only four compromisers were elected. The Congress was opened by the Chairman of the old Army Committee, the Menshevik Pechersky, who deliberately tried to intimidate the delegates:

“Do you realise,” he said, “that we are already at our last gasp, that the country is perishing? . . . Before us is the prospect of the cessation of railway traffic, isolation from the centre, starvation, rioting . . . anarchy and disaster, the certain doom of the country.”[16]

But intimidation was no longer effective. One after another delegates from the different units got up and read the instructions they had received, indicating that their constituents were wholly on the side of the new regime. These instructions expressed a unanimous demand for the immediate dissolution of the old Army Committee. So strong was this demand that the old committee was obliged to place its resignation in the hands of the Presidium of the Congress even before a new committee had been elected.

The Congress adopted a resolution recognising the Soviet regime and pledging unqualified support for the Council of People’s Commissars.

The last item of business was the election of a new Army Committee. The result of the election ensured the Bolsheviks the leading role. A Military Revolutionary Committee was set up, which forthwith proceeded to wipe out all traces of counter-revolution in the army. The struggle had to be waged mainly against the compromisers, whose resistance here was stronger than in any other army on the Western Front. The commanding personnel, having no backing among the troops, remained more or less passive.

The situation in the Third Army during the October days was similar to that which prevailed in the First Army on the Northern Front. The majority of the members of the Committee of the Third Army were Left wing Socialist-Revolutionaries who as soon as the news of the insurrection in Petrograd was received the Committee issued a manifesto calling upon the soldiers to remain calm, but the committees of many of the units of this army had already passed Bolshevik resolutions. A secret report of the Military Political Department of the Staff of the Western Front noted that:

“The colour of these resolutions, which is strongly Bolshevik, indicates that Bolshevik agitation—the growth of which was unanimously reported by all the corps commanders—has not been in vain, and that quite intensive preparations for a Bolshevik insurrection have been made among the troops.”[17]

In another report, special reference was made to the revolutionary temper prevailing in the 15th Corps of the Third Army. The report stated:

“Rumours about current events which have only just reached the masses of the soldiers, threaten to create serious complications; the masses have been corrupted by Bolshevik agitation and may prove to be most susceptible to all kinds of propaganda. The Corps and Divisional Committees are hostile to the Provisional Government, Kerensky and the bourgeoisie.”[18]

One of the first to go over to the proletarian revolution was the 6th Division of the 15th Corps. At a general meeting of Unit Committees of the 6th Division, held on October 29, a resolution was passed welcoming the transfer of power to the Soviets. This resolution was unanimously supported by the 22nd, 23rd and 24th Regiments of the Division, by the Engineers’ Company and by the artillery.

More turbulent was the development of the October events in the 35th Corps of the Third Army. A Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Committee was set up in this corps during the very first days of the October Socialist Revolution. It promptly broke off all connections with the compromising Corps Committee, and established control over the Corps Staff and the commanders. Thus, the Commander of the 55th Infantry Division fulfilled his functions under the supervision of a private. Kerensky’s telegrams were either intercepted, or else delivered with a note refuting their contents.

General D. P. Parsky, Commander-in-Chief of the Army, wanted to send a punitive expedition against the insurgent corps and for this purpose detailed three regiments and two brigades of the 2nd Turkestan Cossack Division, which was stationed in the rear of the Third Army. This division was regarded as being more or less reliable; and with its aid the command hoped to restore “order.” But to put its threat into operation proved to be a task beyond its powers.

On November 2, the Second Congress of the Third Army was held in Polotsk, the headquarters of this army. The Congress was convened by the compromising Army Committee in the hope of obtaining support in the army, but the majority of the delegates proved to be Bolsheviks. To the Presidium of this Congress four Bolsheviks, three Socialist-Revolutionaries, two Mensheviks and one Maximalist Socialist-Revolutionary were elected.

Before the Congress was opened, on November 1, a Conciliation Committee had been set up for the purpose of drafting a general declaration. This Committee consisted of 16 members, four from each of the respective political groups—Bolshevik, Menshevik, Socialist-Revolutionary and Maximalist Socialist-Revolutionary. The Committee sat nearly all night and the whole of the next day. Finally, the Maximalist Socialist-Revolutionaries left the Committee, stating that they would submit their own resolution to the Congress. The rest of the groups reached an agreement on the basis of the decrees on peace and land and the other decisions of the Second Congress of Soviets, as well as the legislative acts of the Council of People’s Commissars; but the resolution it drafted also contained a clause calling for the formation of a “united Socialist government on the basis of agreement between the two camps of democracy.”

Later, at the Congress, the reporters from the different units read the instructions they had received from their constituents. Not one of them spoke in favour of supporting the Provisional Government. The army was on the side of the Bolsheviks. The “conciliatory spirit” displayed by the compromisers in their negotiations with the Bolsheviks can easily be explained. Lacking support in the army they were obliged to manoeuvre in the effort to achieve “agreement between the two camps of democracy.” But the Bolsheviks of the Third Army, although taking the path towards such an “agreement,” were by no means beguiled by these tendencies towards unity. The spokesman for the Bolshevik group said:

“Our program is: power to the Soviets. We are prepared to make concessions to the Right wing of democracy, but we shall not retreat a single step from the aim of deepening and expanding the revolution.”[19]

In the end the resolution drafted by the Conciliation Committee was supported by all the groups with the exception of the small group of Maximalist Socialist-Revolutionaries. The Congress then passed a resolution which proclaimed that from now on all authority in the army was vested in the Army Committee.

In the new Army Committee the Bolsheviks obtained 30 seats, the Socialist-Revolutionaries 22, the Mensheviks four, the Maximalists four and the non-party Socialists six. A Bolshevik was elected chairman; and a Socialist-Revolutionary (the Chairman of the old Army Committee),a Menshevik, and a Bolshevik were elected vice-chairmen. In addition, four secretaries—a Bolshevik, a Socialist-Revolutionary, a Menshevik and a Maximalist Socialist-Revolutionary—were elected. By order of the Congress, the Army Committee set up a Military Revolutionary Committee on which all the groups were represented in proportion to their strength at the Congress.

The Military Revolutionary Committee informed the Commander-in-Chief of the Army that no order of his would be obeyed without its sanction. The Commander-in-Chief had no effective means of resisting this control.

The inter-party agreement reached at the Congress soon broke down, however. At one of the first meetings of the Army Committee the question arose of sending revolutionary reinforcements to Minsk; the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries fiercely opposed this. On a vote being taken 33 votes were cast in favour of the proposal and 24 against. The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries lodged a protest on the ground that the decision to dispatch troops “was contrary to the decision of the Army Congress” and would give rise to civil war, the very thing which they had “exerted all efforts” to avoid. Soon after, the compromisers left the Military Revolutionary Committee, which was pursuing a firm revolutionary line.

The Bolshevisation of the army proceeded at a rapid pace. On November 18, the Military Revolutionary Committee dismissed General Parsky, the Commander-in-Chief of the Army, for refusing to enter into peace negotiations with the Germans. Lebedev, the Chief of Staff and Nechayev, the Chief of the Polotsk garrison, were dismissed at the same time. Sub-Lieutenant Anuchin, Chairman of the Army Committee and a Bolshevik, was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and Chudkov, a private in the Motor Transport Unit, was appointed chief of the garrison. Commissars of the Military Revolutionary Committee were appointed to the various departments at Staff Headquarters. Thus was the October Revolution brought about in the Third Army.

In Minsk, the centre of the Western Front, and the headquarters of the General Staff of that front, news of the events in Petrograd was received on the same day, viz., October 25. The Presidium of the Minsk Soviet, which consisted entirely of Bolsheviks, immediately issued Order No. 1, proclaiming that it had taken over power in the city.

By 2 p.m. that day, the order was posted all over the city. At the same time, all the Bolsheviks who were under arrest were released from the prisons and guardrooms where they had been held and assembled outside the premises of the Soviet in Petrograd Street. While still in custody they had organised a fighting unit, but they lacked arms. Soon, machine guns, rifles and the necessary ammunition were procured from the artillery depot, and the liberated Bolsheviks were formed into what was known as the 1st Revolutionary Minsk Soviet Regiment, which occupied all the sentry posts in the city. The Soviet appointed its Commissars to the Post Office, the Telegraph Office, and other public offices.

None dared challenge the authority of the Minsk Soviet. The Front Committee, the City Duma, and other bodies remained inactive. Even Staff Headquarters of the front, from which most danger was apprehended, calmly received the Commissars appointed by the Soviet.

Desiring not to interfere with the operations of Staff Headquarters of the front, the Minsk Soviet, on October 26, issued an order, in which it stated:

“The Executive Committee hereby informs all units of the front and the local garrison that all the military orders of an operative character issued by General Baluyev, Commander-in-Chief of the Western Front, must be implicitly obeyed. The political side of the activities of Staff Headquarters of the Western Front is practically controlled by the Minsk Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.”[20]

In the evening of the same day, a Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Committee of the Western Region was formed in Minsk, with A. Myasnikov as the Chairman.

Kerensky’s march on Petrograd served as a signal for the agents of the counter-revolution in Minsk to take action. The centre of counter-revolutionary activity was shifted to the Front Committee of the Western Front. On October 27, a “Western Front Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” was formed in Minsk, under the leadership of the Menshevik Kolotukhin, the Provisional Government’s Commissar of the front and a member of the Front Committee. Soon after the formation of this Committee its armed patrols appeared in the town and demanded that the sentries of the Military Revolutionary Committee should surrender their posts to them. The Socialist-Revolutionaries issued a manifesto and had it posted all over the town. At 3 p.m. Cossacks appeared, and the streets and public squares were occupied by other cavalry units. Artillery and machine guns were placed in Svoboda Square. A violent collision seemed inevitable.

The armed forces of the counter-revolution were estimated at approximately 20,000 men. The “Committee for the Salvation” had at its disposal the Caucasian Cavalry Division, stationed in the vicinity of Minsk, a Corps of Polish Legionaries, and other units. Against these the Bolsheviks could muster the 1st Revolutionary Minsk Soviet Regiment, numbering about 2,000 men, and a small detachment of Red Guards, consisting mainly of railwaymen. Of the units of the local garrison only the crews of the anti-aircraft batteries were wholly on the side of the Bolsheviks. The Minsk Soviet did not succeed in getting assistance from the front, which was about 100 kilometres from the town.

Subsequent events proved that the forces of the “Committee for the Salvation” were much less numerous than had been assumed, but they certainly far outnumbered those of the Minsk Soviet. The “Committee for the Salvation” presented an ultimatum to the Military Revolutionary Committee demanding complete submission. Immediately on the receipt of the ultimatum, a conference of the Bolshevik Regional Centre was convened. The alternative that confronted the conference was: either to reject the ultimatum and, relying on the forces available, to enter into an unequal battle, or open negotiations with the “Committee for the Salvation” in order to gain time in which to draw revolutionary units from the front. The Minsk Bolsheviks chose the latter. Negotiations were opened, as a result of which an agreement was reached on the following terms:

“1. The ‘Committee for the Salvation’ abandons the idea of sending armed units to Petrograd and Moscow, and will not permit such to pass through Minsk.

“2. The ‘Committee for the Salvation’ recognises the amnesty granted by the Minsk Soviet to the political prisoners, but is of the opinion that these should be disarmed.

“3. The Minsk Soviet shall appoint two representatives to the ‘Committee for the Salvation of the Revolution.’

“4. The ‘Committee for the Salvation’ shall be temporarily vested with all power in the region of the Western Front.”[21]

The artillery and machine guns were removed from the square. The sentries of the Military Revolutionary Committee surrendered their posts to the units of the 2nd Caucasian Cavalry Division and took up their quarters in the barracks not far from the premises of the Soviet. The town found itself in the power of the “Committee for the Salvation.” Neither side however, adhered strictly to the obligations it had undertaken. The “Committee for the Salvation,” which had undertaken not to transfer troops from the front to Petrograd and Moscow, violated this undertaking at the slightest opportunity. At the same time, the news which was received from the front was not at all encouraging for the “Committee for the Salvation.” Division after division and corps after corps, expressed opposition to the Provisional Government and support for the Soviet regime. The ground was slipping from under the feet of the compromisers. At a meeting of the “Committee for the Salvation” held on November 1, a representative of the Congress of the Grenadier Corps of the Second Army appeared and stated that the Grenadiers condemned the activities of the “Committee for the Salvation” on the Western Front, demanded that it should recognise the revolution which had been brought about and submit to the new government, and threatened to dissolve the “Committee for the Salvation” by force if it failed to do so. The corps would take all measures to secure the fulfilment of these demands, said the representative.[22]

Resolutions were not the only means with which the front came to the assistance of the Minsk Bolsheviks. As soon as the request of the Minsk Soviet for assistance was received by the Second Army, the Military Revolutionary Committee of that army decided to send to Minsk an armoured train which was at the disposal of the Grenadier Corps and was then on the siding at Khvoyevo. A member of the Committee named Prolygin, a railwayman and a sergeant in the army, was commissioned to take the train out. On the morning of October 29, Prolygin arrived at the siding and came to an arrangement with the train crew to move in the direction of Minsk. The officers and the engine-drivers, who refused to submit, were arrested, and Prolygin drove the train himself.

The train moved slowly and cautiously, as there was a danger that the track might be blown up. At Negoreloye Station a delegation from the Minsk “Committee for the Salvation” came out to meet the train and tried to persuade the soldiers not to go any further, but they failed. The train proceeded on its journey. In view of this, the Minsk “Committee for the Salvation” ordered a gang of workers to go out and pull up the railway tracks. On the way the workers learned what was in the wind and arrested their foremen; and on meeting, at Fanipol Station, the delegation of the “Committee for the Salvation” returning from Negoreloye, they arrested them too.

Thus both attempts to hold up the armoured train failed. When this became evident the Menshevik Kolotukhin, Chairman of the “Committee for the Salvation,” together with a staff officer of the Western Front named Zavadsky, rushed off in an automobile in the direction from which the train was travelling. They stopped at the 712th verst post, got out and walked towards the railway track. A small white cloud from an exploding shell rose above the embankment. Noticing this, the workers ran to the scene. Kolotukhin and Zavadsky beat a hasty retreat to the woods, abandoning their car and tools. On arriving at the scene of the explosion the workers found the rails torn up. The design of the counter-revolutionaries to wreck the train failed however, for it had already passed this spot. On the night of November 1 the armoured train arrived in Minsk. It was followed by a battalion of the 60th Siberian Regiment, which had also been dispatched by the Second Army. The arrival of these units put an end to the domination of the “Committee for the Salvation” in Minsk.

A meeting of the Minsk Soviet was held in the theatre. The chief speaker was Comrade Myasnikov, who moved a resolution in favour of endorsing the Soviet regime. Thousands of hands were raised in favour of it. Backed by real armed force, the Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Committee again proclaimed itself the seat of governmental authority on the Western Front. General Baluyev, Commander-in-Chief of the Front, with whose backing the “Committee for the Salvation” had established its short-lived rule in Minsk, was obliged to declare his “readiness” to co-operate with the Bolsheviks. Concerning this, Comrade Kamenshchikov, a participant in the events in Minsk, relates the following:

“In reply to Baluyev’s letter, the Military Revolutionary Committee decided to submit the following demands to him: The cavalry must be immediately withdrawn from Minsk. Colonel Kamenshchikov was to be appointed commander of the troops in Minsk and its environs and also commandant of the town. . . . Baluyev accepted all these demands except one: he refused to issue the order appointing me commander of the troops in Minsk and its environs. I took up that post by order of the Military Revolutionary Committee.”[23]

The relation of forces in Minsk underwent a change. As a result of Bolshevik propaganda, the Caucasian Cavalry Division refused to support the counter-revolution. The attempt of the Menshevik Kolotukhin, Commissar of the front and Chairman of the “Committee for the Salvation” to wreck the armoured train discredited that Committee. On November 4, Kolotukhin himself was arrested.

Thus the Soviet regime triumphed in Minsk, the centre of the Western Front.

Several other points in the rear of the Western Front played an important part in bringing about the proletarian revolution, viz., Orsha, Smolensk and Vyazma.

Orsha, an important railway junction, was on the direct line between General Headquarters and Petrograd, and between Minsk and Moscow. General Headquarters clung to Orsha very tightly. It was no accident that the 2nd Kuban Cossack Division was kept in the environs of the town; its function was to ensure the execution of General Headquarters’ order at this important point. In the very first days of the October Socialist Revolution troops began to arrive here en route for Petrograd and Moscow to crush the proletarian insurrection. The Orsha Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies was controlled by compromisers—Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and Bundists.

The position of the Bolsheviks in Orsha during the October days was an extremely difficult one. At a meeting of the Executive Committee of the Orsha Soviet held on October 6, Colonel Shebalin, commandant of the town, said:

“The Bolshevik insurrection in Petrograd will soon be liquidated. All the main points have already been captured by the cadets. In Orsha we shall crush every attempt at insurrection.”

In reply to this the voices of the Bolsheviks were heard in protest, crying:

“Throw him out! Remove him!”

The Colonel was followed by the chief of the militia Ivanov, a Menshevik. Glancing maliciously in the direction of the Bolsheviks he began his speech by saying:

“On my orders the militia today occupied the railway station. Machine guns have been placed wherever necessary. I shall not permit any Bolshevik outrages. . . .”

A Cossack officer from the Kuban Division assured the compromisers that the Cossacks were entirely on their side.

The Soviet adopted a resolution to form a “Committee for the Salvation.” Representatives of the City Duma were also included in this Committee, whereupon the Mayor of Orsha, the veteran Bolshevik P. N. Lepeshinsky, resigned.

The Bolsheviks conducted energetic activities in the factories and among the units of the garrison. They demanded new elections for the Soviet, and when the compromisers refused to hear of this, the new elections were held without official sanction.

On October 27 a meeting of the Soviet took place at which the Bolsheviks had a far larger representation than before. It was a stormy meeting. The compromisers refused to recognise the credentials of the newly elected deputies.

The Bolsheviks spent the next day, October 28, in the factories and among the units of the garrison. The attempt of the compromisers to prevent the elections from being held failed. At the artillery depot an officer who got up to oppose the Bolsheviks, was almost lynched by his men; he was saved by the Bolsheviks.

The newly elected Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies met that very same day. Not a single compromiser was present. The Mensheviks, Socialist-Revolutionaries and Bundists held a meeting of the old Soviet. At this first meeting of the new Soviet a Military Revolutionary Committee was formed, which immediately established connection with all the units of the garrison and appointed its Commissars to them. It dispatched soldiers to the station to keep watch over incoming trains.

On learning that a Military Revolutionary Committee had been established in Orsha, the Minsk “Committee for the Salvation” appointed the Right Socialist-Revolutionary Makarevich Commissar of the Orsha junction. Makarevich arrived in Orsha on October 29 where he was immediately arrested.

Meanwhile, two troop trains carrying the 623rd Infantry Regiment, which was under Bolshevik influence, arrived in Orsha. The Military Revolutionary Committee held them up at the station and persuaded the men to perform guard duty in the town. With the aid of these soldiers the Kuban Cossack Division was kept in check. Later on, the Bolsheviks won over the rank-and-file Cossacks to their side.

The position of the counter-revolutionaries was becoming precarious. On October 31, the Commander of the Kuban Cossack Division, Nikolayev, who was entrusted with the function of ensuring the free passage of troops going north to assist Kerensky and Krasnov, telegraphed General Headquarters as follows:

“The Bolshevik Committee has brought into the town a company of the 623rd Infantry Regiment, two troop trains of which are still at the station. Large armed units of this Bolshevik force are patrolling the town, particularly the Telegraph Office which is occupied by 10 Cossacks. Tomorrow they propose to occupy all the public buildings and to force upon me their demands, which today I categorically rejected. I have no forces at my command to counteract them; the squadrons from Minsk have not yet arrived; the dispatch of armoured cars is desirable.”[24]

The men of the 623rd Regiment held up 300 Siberian Cossacks who were proceeding from Minsk to Smolensk.[25]

On November 1, Colonel Shebalin, the commandant of the town, who on October 26 had boastfully stated that he would “crush every attempt at insurrection,” telegraphed direct to Dukhonin as follows:

“The situation in Orsha is critical. On the morning of the 1st, Uzlovaya (junction) Station and the town will be in the hands of the Bolsheviks. Ultimatums have been presented to all the authorities. The dragoons have not arrived, I have no means with which to take counter-measures. A whole regiment of infantry is in trains at the station, and this evening a company from this regiment marched into town. To save the situation, send by 8 o’clock, 4 armoured cars and a battery. I am telegraphing over the heads of the intermediate authorities because I am impatient with anxiety.”[26]

But telegrams were of no avail. The Bolsheviks were in complete control of the town. The Orsha Military Revolutionary Committee blocked the dispatch of counter-revolutionary forces from the front.

The Bolsheviks resorted to all sorts of devices to hold up troop trains. Part of the troops they won over, others they disarmed. If resort to force threatened to cause bloodshed, the trains were shunted out to sidings beyond the station and left in such a way that not only was it impossible to unload, but even difficult for the men to leave the cars. After staying on these sidings for a day and a night the soldiers would beg the commandant to dispatch them “in any direction he pleased.”

Smolensk lies on the direct route from Minsk to Moscow. At that time it was the headquarters of the Minsk Military Area, then under the command of General Leshch. The Commissar of the Provisional Government for the Area was Galin, who shortly before had dispersed the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in Kaluga. The town was crowded with troops and army administration officers of the Western Front. The most reliable forces were concentrated around Area Staff Headquarters. A large section of the troops of the garrison, however, favoured the Bolsheviks.

On October 26, immediately on the receipt of news of the insurrection in Petrograd, the Smolensk Soviet met. The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries demanded that the Soviet should condemn the insurrection, but their resolution was defeated by an overwhelming majority. Thereupon they left the Soviet and went to the City Duma, where all the counter-revolutionary forces were gathered. That same day the City Duma announced the formation of a Smolensk “Committee for the Salvation.” The Bolsheviks, who remained in the Soviet, formed a Military Revolutionary Committee consisting of four Bolsheviks, two “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and one Anarchist.

Soon the Military Revolutionary Committee received information that Headquarters of the Military Area had ordered the Cossacks to prepare for an attack on the Soviet. The Bolsheviks began to fortify the building, which formerly had been the Governor-General’s mansion, and placed three mortars in the garden. Distrusting the staff of the Telephone Exchange, they got in touch with the artillery detachment—the unit most loyal to the Soviet—by means of a field telephone line. A military guard was posted in the Soviet building and machine guns were placed at the windows.

The “Committee for the Salvation” proclaimed martial law in the town. Cossacks and armoured cars patrolled the streets. Patrols were also posted on the roads on the outskirts of the town.

By forging the signature of the Chairman of the Military Revolutionary Committee the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries on the “Committee for the Salvation” obtained 41 machine guns from the aviation depot. This “success” encouraged the compromisers and they hastened to other military units, but everywhere they met with a rebuff. In the light artillery detachments the agitation of the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks ended with . . . the arrest of the officers. Then they made an attempt to demoralise the units that were most loyal to the Bolsheviks. With this end in view some unknown person sent a large supply of alcohol to the heavy artillery detachment, but the drunken carousal that began among the men was soon stopped by the intervention of the Bolsheviks. In the town the atmosphere became more tense and it was evident that the inevitable climax was approaching.

At 8 p.m. on October 30 a full meeting of the Smolensk Soviet was opened. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary, M. I. Smolentsev, the delegate who had returned from the Second Congress of Soviets in Petrograd, made his report. Everybody in the crowded hall hung on to every word he uttered. His story of the heroic fight put up by the Petrograd proletariat was greeted with enthusiastic applause. Suddenly, the Right Socialist-Revolutionary Kazakov, accompanied by two military men, appeared in the hall. Kazakov strode to the platform and interrupting the speaker, presented an ultimatum.

“The ‘Committee for the Salvation’ demands,” he said, “that the members of the Soviet should surrender their arms and immediately leave the premises. I’ll give you thirty minutes for this. If the demand is not complied with, fire will be opened on the building.”[27]

This announcement caused consternation in the hall. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries advised the deputies to disperse. The workers’ representatives and the delegates from the army units, however, proposed that the ultimatum should be rejected, but the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries were already making for the doors. In the street they were all arrested by the counter-revolutionaries. About 40 Bolsheviks remained in the building, determined not to submit to the ultimatum. They made ready to defend themselves and dispatched the representatives of the artillery detachment to their unit for assistance, letting them out of the building unobserved. All lights in the rooms and corridors were extinguished.

The Bolsheviks who were standing at the windows saw shadowy figures of Whiteguards in the garden darting from tree to tree, drawing closer to the building. Soon a shot was fired from the garden. This was answered by a shot from the windows. A hot exchange of fire ensued. The Cossacks tried to rush the building, but were hurled back. The attack was repeated several times, but was repulsed every time. The besieging force far outnumbered the defenders, however, and this began to tell. The defenders tried to get into telephone communication with the army units, but they found that the telephones had been disconnected. Suddenly, the field telephone which connected the Soviet with the light artillery detachment buzzed with a message from the representative of the detachment who had been sent for assistance. He reported that measures were being taken to defend the Soviet.

Suddenly, at about 2 a.m. the firing ceased. A delegation from the “Committee for the Salvation,” was seen approaching the building, preceded by the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary Smolentsev, whom the Cossacks had arrested and were bringing along as a hostage. The delegation called upon the defenders of the Soviet to surrender, but the Bolsheviks once again emphatically refused.

The firing was then resumed. Ignoring the bullets of the Whiteguards one of the defenders ran into the garden and trained a mortar on the premises of the City Duma, where the “Committee for the Salvation” was in session. The shell hit the roof of the City Duma building and caused considerable damage. Shortly afterwards the City Duma building and the Military Area Staff Headquarters were bombarded by light artillery. At about 4 a.m. the regiment that was guarding the town marched towards the centre, exchanging shots with the troops of the “Committee for the Salvation.”

The “Committee for the Salvation” was thrown into confusion. It sent another delegation to the Soviet, but the demeanour of this one was quite different from that of the first. It proposed that the hostilities should cease and that representatives be sent to the City Duma for negotiations.

The Military Revolutionary Committee demanded: 1) that the “Committee for the Salvation” be dissolved; 2) that Military Area Headquarters should cease hostilities and immediately withdraw the Cossack units from the town; 3) that all prisoners be released.

After prolonged negotiations the terms of the Military Revolutionary Committee were accepted; but next day the “Committee for the Salvation” and Military Area Headquarters violated the agreement. With the aid of the Cossacks they attempted to seize the artillery batteries. Fighting was resumed. Detachments from the Motor Transport School, from the Guard Regiment and the Sappers’ Battalion came to the artillerymen’s assistance. The Whiteguards fled.

Skirmishes with the forces of the “Committee for the Salvation” occurred in different parts of the town throughout the day on October 31. At last, the units of Military Area Headquarters were disarmed. The Cossacks left the town; some of them were disarmed. On November 1, after the Cossacks had left, Galin, the Commissar of the Provisional Government, fled from Smolensk. After achieving victory in the town, the Military Revolutionary Committee posted strong forces at the railway junction. Several trains which were proceeding to Moscow with troops to suppress the insurrection were held up and the men disarmed.

A by no means unimportant role in holding up troops en route to Moscow to crush the insurrection was played by the Military Revolutionary Committee in Vyazma, which during the October days took over power in that town without encountering resistance. Fighting occurred here later.

On October 29, the Vyazma Military Revolutionary Committee was notified of the approach of a train carrying troops to Moscow. The army units and the Red Guard in the town were immediately mobilised for the purpose of holding up these troops. Late at night, the Military Revolutionary Committee received a telegram from the commander of these forces demanding that it should lay down its arms.

Three trains filled with Cossacks were already at Redyakino Station, only a few miles from Vyazma. Disagreement arose in the Military Revolutionary Committee. By a small majority it was decided to open negotiations and to send delegates to Redyakino Station. The Cossacks took advantage of this to move right up to the town and then refused to negotiate. Only then did the Military Revolutionary Committee move a machine-gun detachment and infantry units against them. Fighting ensued in which the Cossacks sustained heavy losses. To gain time they now expressed willingness to negotiate with the Military Revolutionary Committee, but the latter demanded that they should unconditionally lay down their arms. The Cossack officers were stubborn, however, and firing was resumed and kept up until the Cossacks finally laid down their arms. Other troops, including armoured car detachments, shock troops and machine-gun units trying to proceed to Moscow to assist the Whiteguards, were also disarmed.

In consolidating the success of the Great Proletarian Revolution, the Western Front and its rear played an important role.

[1] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the 85th Infantry Reserve Regiment, Regimental Committee, File No. 448-051, folio 27.

[2] “The October Days in the Army on Active Service,” Proletarskaya Revolutsia, 1925, No. 3, p. 217.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the 85th Infantry Reserve Regiment, Regimental Committee, File No. 448-051, folio 25.

[5] Central Archives of Military History Fund of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armies on the Western Front, File No. 157-792, folio 344.

[6] “How the Bolsheviks Fought at Riga,” Rabochy (The Worker), No. 4, August 28, 1917.

[7] “On the Riga Front,” “Latest News,” Rabochy, No. 1, August 25, 1917.

[8] “Slandering the Soldiers,” “Latest News,” Rabochy, No. 2, August 26, 1917.

[9] “To the Officers of the Staff of the Petrograd Military Area,” Pravda, No. 173, October 30, 1917.

[10] “Resolutions,” “The Voice of the Front,” Pravda, No. 181, November 5, 1917.

[11] “From the Army Military Revolutionary Committee of the Second Army,” Pravda, No. 182, November 7, 1917.

[12] “The Declaration of the Army Congress of the Second Army,” “The Army and the Revolution,” Pravda, No. 188, November 13, 1917.

[13] "Order to the Army and Navy, No. 2,” Pravda, No. 190, November 15, 1917.

[14] “From the Front.” “The 107th Infantry Troitsky Regiment,” Pravda, No. 180, November 4, 1917.

[15] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Staff of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the Western Front, File No. 157-792, folio 243.

[16] “The Third Army Congress,” Golos Desyatoy Armii, (The Voice of the Tenth Army), No. 99, November 8, 1917.

[17] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Staff of the Commander-in-Chief of the Western Front, File No. 157-792, folio 247.

[18] Ibid., folios 241, 242.

[19] “The Second Army Congress (Session of November 3),” “Speech by Comrade Tsarev (Bolshevik),” Golos Tretey Armii, (Voice of the Third Army), No. 155, November 4, 1917.

[20] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] V. V. Kamenshchikov, 1917 on the Western Front (Fragments of Reminiscences). Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

[24] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Staff of the Commander- in-Chief, Quartermaster-General’s Administration, File No. 815, folio 178.

[25] Ibid., folio 179.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

Previous: The October Days at the Northern Front

Next: The Course of the Revolution on the South-Western, Rumanian and Caucasian Fronts