On the Northern Front the news of the revolution in Petrograd spread like wildfire.

On the morning of October 25, an army telegraph operator arrived at the offices of the newspaper Brīvais Strélnieks, and looking round inquiringly for a moment, asked for the editor. The editor responded, whereupon the operator called him aside and furtively handed him a telegram which had arrived from Petrograd by a roundabout way, via Reval and Yuryev. It appeared that the compromising Army Committee of the Twelfth Army had put their members on constant duty at the telegraph instrument and there had held up telegrams addressed to revolutionary organisations. This telegram had also been intercepted, but the operator had made a copy and had brought it to the offices of the Bolshevik newspaper with the suggestion that “it should be brought to the knowledge of the masses.” The telegram ran as follows:

“Last night the enemies of the people passed to the offensive. . . . A plot is afoot to strike a treacherous blow at the Petrograd Soviet. The newspapers Rabochy Put and Soldat have been suppressed.”[1]

The telegram went on to urge that no troops ordered to Petrograd to support the counter-revolution should be allowed to pass. Shortly after this it became known that the Provisional Government had fallen and that a new government was in process of formation.

On the Northern Front there were three armies: the Twelfth, the First and the Fifth. Of these, the most important was the Twelfth Army, which was disposed in the immediate vicinity of the capital. On learning of the insurrection in Petrograd, the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Twelfth Army, which hitherto had existed in secret, immediately came out in the open. It had its headquarters in the town of Venden, quite close to the trenches.

On the morning of October 26 the Military Revolutionary Committee in Venden issued a manifesto in which it announced its existence to the army units and the inhabitants. Following the example of Red Petrograd, it stated, a Military Revolutionary Committee had been formed in the area of the Twelfth Army with the object of uniting all the revolutionary forces of that army. This Military Revolutionary Committee consisted of representatives of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party, of the revolutionary Latvian Social-Democratic organisation, the Bolshevik military organisation in the Twelfth Army, the Executive Committee of the Lettish Rifles, the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies of the Twelfth Army, and also of the Soviets of Soldiers’, Workers’ and Landless Peasants’ Deputies of Venden, Volmar and Yuryev.

“Not a single soldier of the Twelfth Army must be sent to Petrograd for the shameful purpose of ‘pacification,’” said the manifesto.[2]

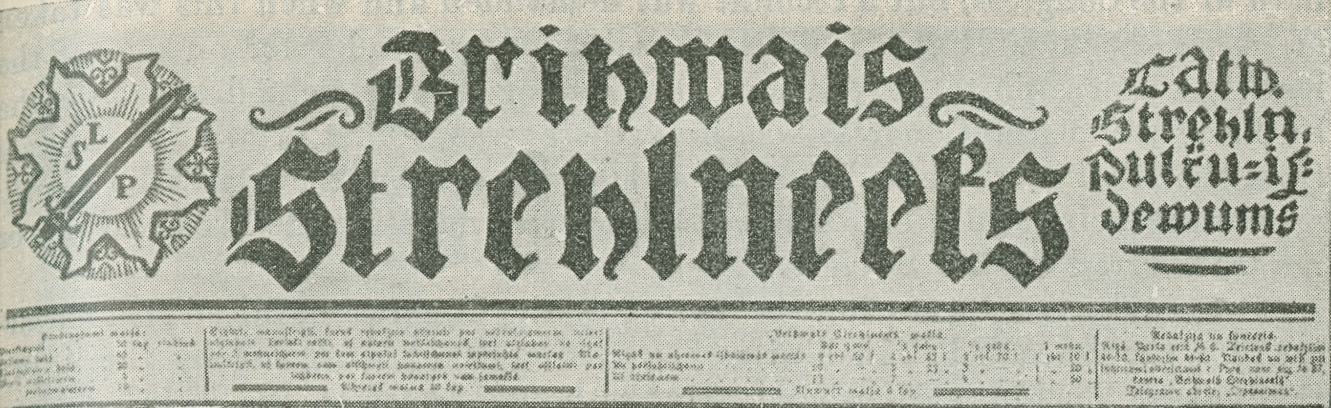

Relying on the Bolshevik military organisation and on the Executive Committee of the Soviets of Lettish Rifles’ Deputies, the Military Revolutionary Committee proclaimed itself the organ of the government in the Twelfth Army. It immediately endorsed the decision of the Executive Committee of the Soviets of Lettish Rifles’ Deputies to call several Lettish regiments from the front for the purpose of occupying the towns of Venden, Volmar and Valk. A Lettish Reserve Regiment stationed in Yuryev was ordered to place itself at the disposal of the local Military Revolutionary Committee and to occupy the railway station in order to prevent troops from being moved in the direction of Petrograd.

All these orders were promptly carried out. On October 27, the 1st and 3rd Lettish Rifle Regiments entered Venden, and the Military Revolutionary Committee thus received the armed forces it required. On October 28 in a conversation over the direct wire with General Cheremisov, Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front, General Y. D. Yuzefovich, Commander of the Twelfth Army, reported as follows:

“The Letts are giving most trouble, and the situation as far as they are concerned is the worst. The 1st and 3rd Regiments, which arrived in Venden yesterday, remained, seized the railway and telegraph stations and arrested many of the officers of two regiments of the 1st Brigade.”[3]

The Lettish Rifle Regiments were among the detachments of the revolution which not only promptly and unhesitatingly went over to the side of the Soviet Government, but actively defended it by force of arms.

In Valk, in the rear of the Twelfth Army, 80 kilometres from Venden, events developed somewhat differently. This town was the headquarters not only of the Staff of the Twelfth Army, but also of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies of that army. This body, which was bitterly hostile to the Soviet Government, had been in office without new elections since the spring, and, therefore, had remained predominantly Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik. It conducted a furious campaign against the Bolsheviks. It issued manifestos assuring General Headquarters and Kerensky of the full support of the Twelfth Army. It sent “detachments of the Death Battalion” to tear down the posters of the Military Revolutionary Committee. Its shock troops even attempted to raid the offices of the Brīvais Strélnieks, but on encountering a guard of armed Letts they beat a hasty retreat.

Convinced that it lacked the forces to resist the revolution, this body decided to open negotiations with the Bolsheviks in order to play for time until the Army Command found troops with which to protect Valk and to continue the struggle against the Bolsheviks. In the evening of October 26, this Soviet offered to open negotiations with the Bolsheviks. The offer was accepted and the negotiations lasted all night. The Bolsheviks adopted a perfectly clear position—all power must be transferred to the Soviets. After quibbling for a long time the Army Soviet at last pledged itself not to take any hostile action; but the very next morning it formed a “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” for the area of the Twelfth Army and resumed its campaign against the Bolsheviks with redoubled vigour.

Meanwhile, taking advantage of the negotiations, General Yuzefovich, Commander of the Twelfth Army, began to concentrate his most reliable troops in Valk. In a conversation with Cheremisov on the direct wire on October 28 he reported:

“From the moment the mutiny started I deemed it necessary, in view of the gravity of the situation, to move to Valk the 20th Dragoon Regiment and, moreover, I have ordered the rest of the regiments of the 17th Cavalry Division to move nearer to the vicinity of Valk. . . . We cannot allow the Letts to capture Valk.”[4]

But this was of no avail. On October 29 the 6th and 7th Lettish Rifle Regiments reached Volmar, half-way between Venden and Valk. These revolutionary regiments were on the march to the latter town where the Staff of the Twelfth Army was situated. Two or three days later Yuzefovich reported to Cheremisov the following:

“I have no effective forces. . . . The 17th Cavalry Division is more reliable, but it has passed a resolution to remain neutral and to go into action only to put a stop to riot and plunder.”[5]

In the last days of the month, while the revolutionary regiments were on the way to Valk, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks called a Congress of the Twelfth Army in Venden. The delegates for this Congress had been elected before the October events and the elections had been strongly influenced by the Socialist-Revolutionaries. At the Congress the vote split into two almost equal parts, one in favour of the Bolsheviks and “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, and the other in favour of the Mensheviks and Right Socialist-Revolutionaries. Of the seven seats in the Presidium three were won by the Bolsheviks. S. M. Nakhimson, a Bolshevik, was elected chairman of the Congress, but a recount was demanded and when this was taken M. A. Likhach, a Right Socialist-Revolutionary, and later on one of the leaders of the White government in Archangel, was elected. Outside the building where the Congress was held there was a vast crowd of soldiers from the local garrison and numerous delegations from the front who loudly expressed their solidarity with the Bolsheviks and demanded that all power be transferred to the Soviets.

On nearly every question the voting at the Congress resulted in a majority for the so-called “Kuchinites,” i.e., the Right wing led by the Army Commissar Kuchin, a Menshevik. But although Chernov, the Socialist-Revolutionary chief, was present at the Congress, the vote on the attitude to be taken towards the October Revolution resulted in a victory for the Left bloc, which polled 248 votes against 243. The new Army Committee was elected on a parity basis, 22 members from the Right and Left blocs respectively.

During the election the Bolsheviks advanced the following demands, which the Congress adopted:

1. Another congress must be called in two weeks’ time at which a new Army Committee is to be elected.

2. The new Army Committee must not contain a single one of the old members of the Executive Committee of the Army Soviet, i.e., the Kuchinites.

3. The “Committee for the Salvation” must cease its activities.

The newly elected Army Committee had two chairmen: one a Menshevik and the other a Bolshevik. Under these circumstances the Committee was, naturally, unable to do effective work.

Meanwhile, the Lettish regiments were nearing Valk. On November 4 Yuzefovich reported to Cheremisov:

“This morning, the 6th Tukkum Regiment left Volmar on its own accord, and with four officers proceeded to Valk in marching order, intending to spend the night in Stakelin, where it is to be joined by the 1st Battery of the 42nd Heavy Artillery Battalion. . . . There are rumours that the 7th Regiment will follow the 6th to Valk.”[6]

Yuzefovich complained that he had no means of preventing these movements of the Bolshevistically-minded regiments. To this Cheremisov replied:

“What can I do to help you? If you have no reliable troops to depend upon, still less have I.”[7]

It was perfectly true, no troops loyal to the tsarist generals could be found, although there were more troops on the Northern Front than on any other. This explains the consternation and irresoluteness of the High Command, and of Cheremisov in particular.

On November 5, the 6th Lettish Regiment, headed by a band, marched into Valk. The actual leadership of the army passed into the hands the Bolsheviks. At the Special Congress of the Twelfth Army held on November 14 and 15, the Bolsheviks had an overwhelming majority. The Left bloc at the Congress, headed by the Bolsheviks, won 48 out of the 60 seats on the Army Committee, while the so-called “Socialist” bloc, consisting of the Mensheviks, Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and Trudoviki, won only 12 seats.

The centre of the Northern Front was occupied by the First Army, which had its headquarters in the township of Altswannenburg. Here the October events did not develop as smoothly as in the Twelfth Army. At the very beginning of the October Revolution the Army Committee of the First Army expressed opposition to the idea of supporting the Provisional Government. In a conversation with Dukhonin over the direct wire, on October 26, General Lukirsky stated:

“The First and the Fifth Armies have declared that they will follow not the government, but the Petrograd Soviet. I am informing you of the decision of the Army Committees.”[8]

Later, however, the Army Committee of the First Army wabbled very considerably, and in this reflected the tactics of the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, who exercised considerable influence over the Committee. While refusing to render the Kerensky government any assistance whatsoever, the Committee lacked the determination to recognise the new government. The enemy took this as a sign that the Committee was changing its position. On October 29, General Lukirsky, in a conversation over the direct wire with General N. V. Pnevsky, Chief of Staff of the First Army, stated the following:

“The Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front has just informed me . . . that the Committee of the First Army has decided to support the Provisional Government.”[9]

On these grounds Lukirsky proposed that “corresponding infantry units, fully reliable, should be chosen from this army to join Kerensky’s troops which are mustering near Petrograd.”[10]

Pnevsky expressed surprise at this and said that evidently there was some misunderstanding, for the Army Committee “was by no means inclined to support the Provisional Government.” “There are no absolutely reliable regiments in that army,” he added.[11]

On October 31, the First Army received from Gatchina a demand, signed by Kerensky, for troops to be sent near Petrograd. Next day, Baranovsky, Quartermaster-General of the Northern Front, telegraphed to Kerensky and to Dukhonin as follows:

“Communicating following telegram: ‘Neuswannenburg, October 31, 1 p.m. With reference to telegram No. 174, 12:20 p.m., October 31, from Gatchina Palace, signed by Kerensky, Avksentyev, Gotz, Voitinsky, Stankevich and Semenov, I hereby report that the Congress of the First Army has unanimously resolved not to send a single regiment. Notbek.’”[12]

Thus ended all the attempts of the enemies of the revolution to obtain reinforcements from the First Army. After this, the Command of the First Army did not dare even so much as hint at sending troops.

On October 30 the Second Congress of the First Army was opened in Altswannenburg. The Congress was attended by 268 delegates, of whom 134 supported the Bolsheviks, 112 supported the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and the rest supported the Internationalist Mensheviks. The Bolshevik group, however, lacked Party leaders. As Lieutenant S. A. Sebov, the Vice-Commissar of the First Army, stated in describing the proceedings of the Congress:

“Among the Bolsheviks there did not appear to be any leading Party workers, and even their reporter, an officer, stated that although he was speaking on behalf of the Bolsheviks, he himself was not a Bolshevik, but was simply imbued with the spirit of the masses.”[13]

On the main item on the agenda—the current situation—two resolutions were submitted to the Congress, one by the Bolsheviks, and the other by the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries. The Bolshevik resolution demanded unqualified recognition of the Soviet Government and immediate support for it by armed force. The Socialist-Revolutionary resolution, while not denying recognition of the Soviet Government on principle, proposed that the question of rendering it armed assistance be postponed until “the situation became clear.” The latter resolution was supported by the Internationalist Mensheviks. The voting resulted in a tie. A “Conciliation Committee” was elected, which submitted the following formula to the Congress:

“In the event of the receipt of information of a counter-revolutionary movement, half of the army shall move to Petrograd, while the other half shall remain at the front.”[14] This formula was adopted.

The Congress adopted a manifesto which was sent out by telegraph addressed: “To All! To All! To All!” The manifesto stated:

“We deem the Kerensky government deposed and request that you join the First Army and support the Military Revolutionary Committee.”[15]

The Congress also adopted a resolution demanding the formation of a “homogeneous Socialist government,” to which was added the proviso that in this government the parties should be represented “in the same proportion as at the Second Congress of Soviets.”[16] Twenty-five delegates voted against this resolution and 30 abstained from voting.

Thus, the Congress slipped into the position of the compromising parties, although the rank and file of the army were on the side of the Bolsheviks.

The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries boasted that at the Congress they had secured the adoption of “neutral” resolutions, but this did not help them to neutralise the masses of the soldiers. Speaking of the soldiers of the First Army, the above-mentioned Lieutenant Sebov observes with a note of chagrin:

“The success of the Bolshevik movement is the cause of great joy among them. No government but a Bolshevik government, or rather, a peace government, can be successful.”[17]

The Congress elected a new Army Committee of 60 members, some of whom were elected as representatives of their respective political groups and some as representatives of the different army divisions. The Bolsheviks had 35 seats, the Socialist-Revolutionaries 19, and the Mensheviks six. The newly elected chairman was a Bolshevik, and of the two new vice-chairmen, one was a “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary and the other a Menshevik. Two secretaries of the Presidium were elected, one a Bolshevik and the other a “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary. Thus, the very composition of the Presidium of the new Army Committee of the First Army, in which the two Bolsheviks were opposed by three compromisers, old hands at the political game, prevented the Bolsheviks from carrying through the line of their Party.

The Army Committee continued to wabble until the middle of November, when another Army Congress was called, which provided firmer Bolshevik leadership. But there can be no doubt that even in the initial period of the October Revolution, the First Army was entirely on the side of the Bolsheviks. Some of its units were ready to support the Soviet Government by force of arms. All the attempts of the counter-revolutionaries to obtain reinforcements from the First Army failed.

The left flank of the Northern Front was occupied by the Fifth Army with headquarters in Dvinsk. On the night of October 24, E. M. Sklyansky, the Chairman of the Army Committee, a Bolshevik, then in Petrograd as a delegate to the Second Congress of Soviets, informed the Bolsheviks in the Fifth Army of the insurrection which had started in the capital. On receipt of this information the Bolshevik group in the Army Committee immediately set up a Military Revolutionary Committee. On October 27, the latter informed the Petrograd Soviet that armed units from the Fifth Army could be sent to Petrograd to support the insurrection.

Meanwhile, General Headquarters was persistently demanding that troops should be sent to assist Kerensky. The Command of the Fifth Army was willing to carry out this demand but, as General Popov, its Chief of Staff, informed General Lukirsky in a conversation over the direct wire, this task was complicated by the “Bolshevik temper of the Army Committee and of the other newly elected committees.” Popov then went on to inform Lukirsky that the Army Committee had received a telegram from the Second Congress of Soviets requesting that units of the Fifth Army be sent to reinforce the insurgent Petrograd garrison. This telegram was discussed at a meeting of the Army Committee and “was defeated by a fluke majority,” he added.

Next day Popov reported to General Baranovsky at the Headquarters of the Northern Front the following:

“An acute situation is arising in the army. . . . Last night the Army Committee, by a majority of only three votes, decided to send to Petrograd 12 battalions, 24 machine guns and cavalry, artillery and units of engineers, ostensibly for the neutral purpose of settling the conflict in Petrograd. Today, October 30, the representatives of the Bolshevik section of the Army Committee called on the Commander-in-Chief of the Army and demanded that this decision be carried out. The Commander-in-Chief categorically refused and decided to prevent the Army Committee from carrying out its intention at all costs, and to use all the means available for the purpose with the utmost determination. Consequently, a special column, comprising three arms, has been mustered in Dvinsk and at the Dvinsk railway junction. Furthermore, the 1st Cavalry Division has been ordered to block the railway at Rushony Station. . . . According to information received, the Army Committee has decided to arrest the Commander-in-Chief, the Staff and the Commissars.”[18]

These conversations over the direct wire reflected the intense struggle that flared up in the Fifth Army around the question as to which side to support: the revolution or the counter-revolution. The Army Command attempted to render effective assistance to Kerensky. On October 29, the Staff of the Northern Front ordered the urgent dispatch of the 1st Armoured Car Detachment to be placed at Kerensky’s disposal.

Next day, at 3:40 p.m., General V. G. Boldyrev—subsequently a member of the active counter-revolutionary Regeneration League, and member of the Directorate which paved the way for the Kolchak government in Siberia—began to carry out this order, but the relation of forces was such that to do so he had to resort to a ruse. To prevent the dispatch of the Armoured Car Detachment from reaching the knowledge of the Bolsheviks who were watching the railway stations, a detachment of six armoured cars was sent by road to Rezhitsa, 85 kilometres from Dvinsk. Here the cars were to be loaded on a train, to proceed further in the direction of Petrograd.

“Entrainment at Dvinsk was impossible,” General Baranovsky reported to Dukhonin.[19]

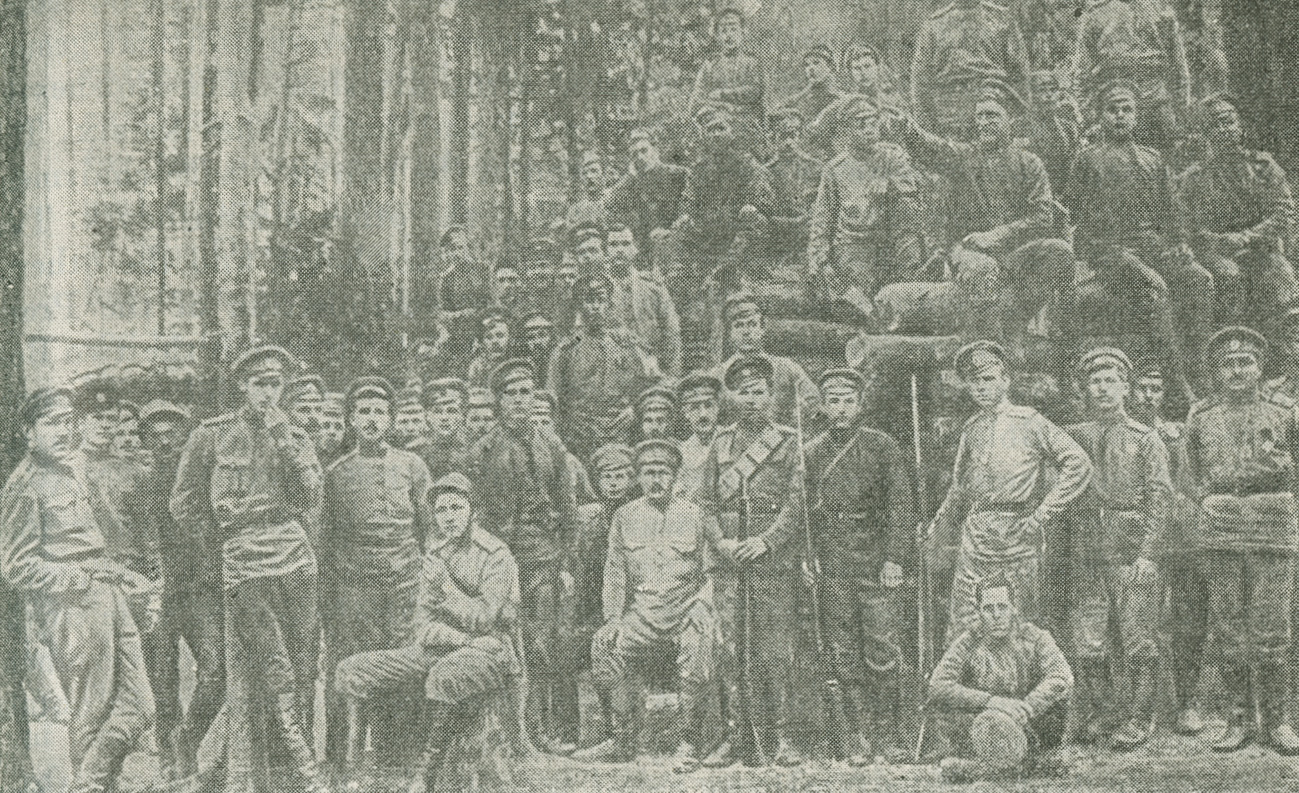

The Bolsheviks learned of the dispatch of the detachment early next morning and immediately picked from the reliable units a small detachment of about thirty men, with five machine guns and sent them by rail to Rezhitsa to intercept the armoured cars and turn them back to Dvinsk. On arriving at Rezhitsa, the commander of the detachment saw that armoured cars were being loaded on the flat cars of a freight train. To prevent the train from proceeding on its way the rails were torn up at a short distance from the station. Being small in numbers, this Bolshevik detachment could not at once launch a frontal attack against the well-equipped armoured cars. After pulling up the rails and leaving several men at the station for observation, the commander and his men went into the town to seek reinforcements; but except for the Guard Company, and about 150 men confined in the guardroom for expressing opposition to the Provisional Government, there were no military units in Rezhitsa. Without wasting time, the men of the Bolshevik detachment set off for the guardroom, released the prisoners, supplied them with arms and equipment from the garrison stores and, in addition, procured ten machine guns.

The Bolshevik detachment thus grew to a force of 200 men with ten machine guns. This force suddenly attacked the Armoured Car Detachment just as they had finished loading the cars on the train and were ready to proceed on their way. Part of the detachment went over to the side of the Bolsheviks. The commander and officers, who had offered resistance, were arrested and detained in the very guardroom from which the men who had just attacked them had been released. The train, loaded with armoured cars, was turned towards Dvinsk.

While these events were proceeding, Dukhonin, speaking to Baranovsky over the direct wire, said:

“Please tell me whether the Armoured Car Detachment is leaving. It must be dispatched forthwith. . . . I order this in the name of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, and request you to inform me by telegraph of the execution of the order, for it is extremely urgent.”

“I shall transmit your order at once,” Baranovsky hastened to answer, and he went on to inform Dukhonin that the detachment “had entrained in Rezhitsa, but was later detained and the commander of the train arrested.”[20]

This was the decisive moment. The Bolsheviks had proved that they had effective support in the army. The Army Command realised that they were on dangerous ground and could offer no resistance to this formidable popular force. By November 1 all the most important army institutions in Dvinsk—the centre of the area occupied by the Fifth Army—were in the hands of the Bolsheviks. The bulk of the soldiers were on the side of the Soviet Government.

General Boldyrev, the Commander of the Army had been reluctant to confess that he was losing authority. The previous day, replying to an enquiry made by General Cheremisov over the direct wire as to whether it was true that the Military Revolutionary Committee was preventing the transmission of certain telegrams, he had said in a contemptuous manner:

“Is that likely of a committee which plays practically no role? On the first day it tried to play the high hand and even countermanded my orders, but on receiving a stern rebuff it abandoned these attempts.”[21]

On November 1, however, in another conversation with Cheremisov, he sang a different tune. He said despondently:

“This is what happened. Dvinsk is practically in the hands of the Army Committee. . . . The arrest of the commanding personnel is by no means precluded. True, the Chairman of the Army Committee has just informed me that there is no danger from that quarter, as they too recognise our authority as regards the conduct of operations and preserving the stability of the front, but in view of the lack of effective forces anything may happen.”[22] “So far, the entire leadership is in the hands of the Bolshevik Army Committee,” he observed in concluding his report to Cheremisov.[23]

That is how the October days passed off in the Fifth Army, which was one of the first to come over entirely to the side of the Soviet Government.

Meanwhile, grave events were unfolding in the rear of the Northern Front. The counter-revolutionaries there tried to muster forces for the purpose of commencing decisive operations against Petrograd, but they met with resistance at every step. The struggle raged mainly at the railway junctions, in the centre of which was Pskov, the headquarters of the Staff of the Northern Front and of its numerous administrative departments. The small provincial town of Pskov had scarcely any working-class population. The presence of the Staff of the front, and of other military bodies with their huge retinue of officers, was unfavourable for the extensive organisation of the revolutionary forces. Moreover, at the beginning of the October events, the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries predominated in the local Soviet.

The Bolsheviks had a firm footing in several of the units of the garrison and in several factories, but the issue here was decided, not only by the relation of local forces, but also by the arrival from the front of units which General Headquarters were sending to assist Kerensky. The local Bolsheviks were confronted with the task of winning these troops to the side of the proletarian revolution, or, if this proved unsuccessful, at least to neutralise them and, in the last resort, to prevent these armed forces from proceeding further against Petrograd.

At the very beginning of the October events the Bolsheviks in the Pskov Soviet succeeded in getting a decision passed to set up a Military Revolutionary Committee. In their confusion, the compromisers allowed candidates nominated by the Bolsheviks to slip into the Committee. After that, on the motion of the Bolsheviks, new elections for the Pskov Soviet were appointed. The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries agreed to this under pressure of the armed workers and soldiers who came to the meeting and demanded that the Soviet should be immediately dissolved and new elections held. The newly elected Soviet assured the Bolsheviks of its complete support.

When Kerensky arrived in Pskov after his flight from Petrograd, the situation he found there was such that he thought it wiser not to show himself in public; in this he was strongly supported by Cheremisov, the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front. On October 27, in a conversation with Dukhonin over the direct wire, General Lukirsky described the situation in Pskov as follows:

“So far, things are quiet in the Pskov garrison and the temper of the men is satisfactory. Last night there was a stormy meeting of the Executive Committee of the United Organisations of the Northern Front. It resolved to arrest all the Commissars and to take all the government institutions under supervision. Early this morning the Revolutionary Committee took 200 men from the infantry garrison under its command. A few moments ago they posted a guard at the Telegraph Office of the Staff of the Northern Front in order to control all correspondence. I am talking to you on the instrument at the house of the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front.”[24]

While this conversation was taking place, the Military Revolutionary Committee was already beginning to occupy the post, telegraph and other offices. Just at that moment, however, the Cossacks who were on the way to assist Kerensky suddenly appeared on the scene. They occupied the railway station, the artillery depots and the barracks, and arrested several members of the Military Revolutionary Committee. Evidently, this was a force of two Cossack Hundreds which General Lukirsky, by order of General Headquarters, had detained specially for the purpose of gaining control of the situation at this extremely important railway junction, and in the immediate rear of Krasnov’s “army.”

The members of the Military Revolutionary Committee who had escaped arrest quickly mobilised a reserve battalion and a motorised company, and that night, the revolutionary units attacked the Cossacks. In the course of the fighting several men were wounded, but the Cossacks were surrounded. Realising that they were overpowered, they promised to take no part in suppressing the revolution. Later on the situation in Pskov fluctuated as different army units arrived. On October 28, Lukirsky informed Dukhonin that the guards of the Military Revolutionary Committee had been withdrawn from the Telegraph Office. Cheremisov reported the same thing to General Yuzefovich, the Commander-in-Chief of the Twelfth Army.

“Here, in Pskov,” he said, “the Revolutionary Committee painlessly dissolved last night; the control over the telegraph instrument was removed earlier in the evening.”[25]

But on October 28, General Lukirsky, by order of Cheremisov, urged the Fifth Army to hasten the dispatch of the 3rd Urals Cossack Regiment to Pskov.

“This is necessary,” he said, “in view of the disorders that are developing in Pskov, near the prison and the distribution centre. . . . Besides that it is extremely necessary to supplement the Pskov garrison with an absolutely reliable infantry unit: a regiment, or a shock battalion.”[26]

But no “reliable” units from the front arrived, and all the efforts of the Staff of the Northern Front to find such were in vain. By this time the Bolsheviks had liberated from the Pskov prison over 300 soldiers and several officers who had been arrested under Kerensky for expressing opposition to the Provisional Government. These released prisoners considerably augmented the forces of the Military Revolutionary Committee, which, in spite of Cheremisov’s assurances, had no intention of dissolving.

General Cheremisov, the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front, understood the temper of the soldiers better, perhaps, than any of the other generals. This young commander, who was reputed to be “democratically minded,” came to the forefront during the February Revolution. During Kerensky’s June offensive he was in command of the Twelfth Army Corps, which broke through the enemy’s lines. His relations with Kornilov were strained. When the latter relinquished the post of Supreme Commander-in-Chief, Cheremisov was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the Northern Front. Weighing up the situation in the very first days of the October Socialist Revolution he opposed the idea of sending troops from the front to assist Kerensky. True, this was prompted not by friendly sentiments towards the revolution, but by the conviction that the task was an impossible one. Probably, his detestation of the petty-bourgeois parties, which he regarded as being mainly responsible for discrediting the commanding personnel in the eyes of the soldiers, had something to do with it. This is vividly revealed by the following remarks uttered in conversation with General Yuzefovich which he held over the direct wire on November 4.

“The notorious ‘Committee for the Salvation of the Revolution,’ which belongs to the party that has ruled Russia for about eight months and has persecuted us, the commanding personnel, as counter-revolutionaries, and now has its tail between its legs, is slobbering and begging us to save them. While the Bolsheviks are successfully carrying on propaganda among the troops, these gentlemen do nothing but quarrel among themselves and call for help from the commanding personnel. It is absolutely disgusting.”[27]

One cannot but admit that the description is very apt.

Voitinsky, the Commissar of the Northern Front, took a different attitude. He had previously belonged to the Bolshevik Party but had been expelled at the beginning of the February Revolution and had joined the Menshevik camp. During the October days he came out as an uncompromising enemy of the Soviet Government. To offset the Military Revolutionary Committee in Pskov he organised a “Committee for the Salvation of the Country and the Revolution” with its headquarters in the Commissar’s office, and this committee gradually set up numerous branches at the front and in the rear.

Accompanying Kerensky in his crusade against Petrograd, Voitinsky unceasingly called upon the Staff of the front to send reinforcements, but all these efforts were futile. The Bolshevik forces grew daily. Subsequent attempts to move the Cossacks north of Pskov encountered the armed resistance of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

On November 3, in a conversation with Dukhonin over the direct wire, Cheremisov conveyed to the latter the report of N. S. Trikovsky, chief of the Pskov garrison, who described the situation in Pskov as follows:

“I hereby report that the local garrison of the town of Pskov is entirely in the hands of the revolutionary organisations of the extreme trend, and is in touch with the Military Revolutionary Committee of Petrograd.”[28]

Thus, the revolution was victorious in the rear of the Northern Front, the most important in relation to revolutionary Petrograd. The attempts of counter-revolutionary General Headquarters to entrench itself in the rear of the Northern Front and to use this as a place d’armes for an attack on Petrograd were thwarted. In relation to the other fronts, where the counter-revolutionaries still continued their endeavours to muster forces, the Northern Front became the outpost of the proletarian revolution.

[1] “The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Rabochy Put, No. 45, October 25, 1917.

[2] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

[3] “October at the Front,” Krasny Arkhiv, 1927, Vol. 4 (23), p. 180.

[4] Ibid., pp. 180-181.

[5] Ibid., Vol. 5 (24), p. 74.

[6] Ibid., p. 75.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., Vol. 4 (23), p. 161.

[9] Ibid., p. 186.

[10] Ibid., pp. 186-187.

[11] Ibid., p. 187.

[12] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Staff of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armies on the Northern Front, File No. 222-092, folio 348.

[13] Ibid., File No. 222-778, folios 123, 124.

[14] “The Report of the Representative of the 88th Petrovsky Infantry Regiment,” Pravda, No. 181, November 5, 1917.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Central Archives of Military History, Fund of the Staff of the Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the Northern Front, File No. 222-778, folio 114.

[18] “October at the Front,” Krasny Arkhiv, 1927, Vol. 4 (23), p. 190.

[19] Ibid., Vol. 5 (24), p. 90.

[20] Ibid., pp. 88, 89, 90.

[21] Ibid., Vol. 4 (23), p. 192.

[22] Ibid., Vol. 5 (24), p. 71.

[23] Ibid., p. 72.

[24] Ibid., Vol. 4 (23), p. 164.

[25] Ibid., p. 178-179.

[26] Ibid., p. 189.

[27] Ibid., Vol. 5 (24), p. 78.

[28] Ibid., p. 99.

Previous: At General Headquarters

Next: The October Days on the Western Front