The refusal of the Provisional Government to accept the ultimatum of the Military Revolutionary Committee necessitated decisive military operations against the Winter Palace. The time limit had long expired. The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party heard a report on the progress of the fighting at the palace. Lenin sent a dispatch to Podvoisky and Chudnovsky ordering them to expedite the capture of the Winter Palace.

Meanwhile, messages were sent to the district headquarters of the Red Guards calling for additional detachments. A call to arms was sounded in the factories. Additional Red Guards were enrolled. Group after group, the workers of the Vyborg District made their way to the Vulcan Works. There, in the courtyard, separated from the embankment by a high iron railing, were stacks of cases of brand new rifles; they had just been brought from the Sestroretsk Small Arms Factory.

The courtyard was flooded with electric light. Workers were busy opening the cases. A number of motor trucks stood waiting. Detachments of Red Guards arrived in the courtyard in a continuous stream. Above the noise of the axes, the crack of wooden cases being opened and the whirr of automobile engines, words of command were heard. Work proceeded methodically and unceasingly; and detachment after detachment of armed Petrograd workers went off, singing lustily, to storm the Winter Palace.

Red Guard units streamed towards the palace from all sides: from the Okhta, the Moscow District, Vasilyevsky Island, and from the Narva and Nevsky Districts. The Putilov Works sent several detachments; on the way, these were joined by workers from Siemens-Schuckert and the Skorokhod Factory, and together they took up stations alongside the Alexandrovsky Park. The Red Guards of the Sestroretsk Small Arms Factory sent out a second detachment of 600 men who, carrying a huge streamer inscribed with the proud word “Revolution,” landed in Novaya Derevnya and marched on foot to the palace.

The Petrograd District mustered a second large mixed detachment consisting of Red Guards from small factories, such as Duflont, Langenzippen, the tramway repair works, the aeroplane factory, Shchetinin’s, the cable factory, and others. P. A. Skorokhodov, the energetic Chairman of the District Soviet, formed a unit. The Red Guards were provided with an armoured car. To expedite the dispatch of forces, many units, including a women’s first-aid unit, were put on motor trucks. The forces from the Petrograd District were sent to the palace embankment and there took part in the general assault.

A detachment was formed of men in the Convalescents’ Battalion in the Naval Hospital. Sailors went to the barracks of the 2nd Reserve Crew, obtained rifles, armed themselves and issued rifles to the lower ranks of the hospital staff.

Scores of small Red Guard units, after capturing various government institutions, also made their way to the Winter Palace. The workers were in high spirits, exhilarated by success. They took their places in the ring around the palace, where, in the front ranks of the besiegers, workers’ overcoats mingled with the black blouses of the sailors. The men were impatient, eager to go into battle and smash the resistance of the numerically small but firmly entrenched defenders of the bourgeois Provisional Government.

At 9 p.m. the Fortress of Peter and Paul gave the prearranged signal. The Aurora followed suit. After this a field gun was hauled under the arch of the General Headquarters building and a shell was fired. It hit the cornice of the palace. The report of the gun was echoed by an outburst of rifle and machine-gun fire on both sides.

An attempt on the part of some units of the Red Guard and sailors to advance into the square was countered by the fire of the cadets.

The vast square was like a desert. It provided no cover whatever. This hindered the advance on the palace, which was surrounded by barricades.

After it had received the ultimatum, the government left the Malachite Hall, from the windows of which they could see the sinister lights of the Aurora, and went to the inner apartments. Here they could not see the cruiser, and the cannonade was not so audible.

The Ministers paced up and down the Field Marshal Hall, engaged in anxious conversation. Suddenly, from above, a shout was heard: “Look out!” All scattered in different directions. A sailor holding a hand grenade was bending over the railing of the gallery. A few seconds later there was an explosion. Palchinsky and a group of cadets rushed to the gallery, seized the sailor and triumphantly dragged him down. Only one cadet had been injured by the explosion but the appearance of the sailor on the upper floor of the palace accelerated the demoralisation of the cadets of the 2nd Oranienbaum School. They refused to stay in the palace any longer, and it was only the frequent exchange of firing in the street that prevented them from leaving.

At 10 p.m. a company of the Petrograd Women’s Shock Battalion, no longer able to stand the fire of the besiegers, surrendered. As they left the palace they were accompanied by a large section of the cadets of the Northern Front Officers’ Training School and by groups from other schools. Firing on both sides temporarily subsided.

At 10:5 p.m. the Provisional Government drafted and dispatched a telegram addressed “To All! To All! To All!” in which it announced that it placed itself under the protection of the army and the people.

General Headquarters communicated to the Winter Palace a dispatch from the Commander-in-Chief, Dukhonin, stating that the Cossack units would arrive in Petrograd on October 26, and reporting what other assistance could be rendered.

At about 11 p.m. firing was resumed. Owing to the Provisional Government’s obduracy, the Military Revolutionary Committee was obliged to order the Fortress of Peter and Paul to bombard the Winter Palace.

Meanwhile, the sailors from the Naval Gunnery Practice Grounds who had been sent by order of Sverdlov, had arrived at the fortress. They examined the guns and found them quite fit for action. Receiving the command, they opened fire, discharging in all 35 shells. Of these, only two struck the palace, one bursting in a room next to the one occupied by the members of the Provisional Government. Although the shelling did little material damage, its effect upon the morale of the besieged was enormous. Between the Aurora and the fortress—where the staff directing the siege of the Winter Palace had its headquarters—communication was maintained by means of flashlights. The Aurora was signalled: “Open rapid fire with blank shells.” The Aurora supported the fortress with her heavy guns. True, she fired blank shells but, accompanying as it did the fire of the fortress guns, the effect was terrifying.

Simultaneously with the artillery salvos, the rifle and machine-gun fire on both sides increased in intensity. The forces of the Military Revolutionary Committee attacked from the side of the Palace Square. This attack, however, was repulsed, and only a small group of about 50 daring Red Guards succeeded in breaking through the barricades to the main gates of the palace, where they were surrounded by cadets and disarmed.

The siege had been going on for about six hours. Many of the Red Guards and soldiers had been near the palace since the early morning without a break. Field kitchens began to arrive and supplied the soldiers and workers with food. Red Guard tramwaymen sent a message to their depot through the conductors and drivers to the effect that as the assault on the palace was being delayed, it would be necessary to send provisions.

On receiving the message, members of the depot committee obtained provisions and loaded them on a streetcar. Soon, in the dark autumn night, a lone, brightly-lit streetcar was tearing at full speed through the silent streets of Petrograd carrying food for the Red Guards. A little later several more cars, filled with Red Guards, arrived near the Palace Square.

The part played by the working women in those eventful days of the proletarian insurrection, although unostentatious, was truly heroic. All the large detachments of the Red Guards had women first-aid units, and in many cases women fought in the ranks. There were also several separate first-aid units composed of women. At a small clothing factory in Vasilyevsky Island, 50 women were employed. All of them joined the first-aid unit. On October 25, breaking up into small groups, they joined the Red Guard Hundreds and remained on duty outside the Winter Palace all night, rendering first aid to the wounded.

Rifle and machine-gun fire at the palace continued unabated. This, and the roar of artillery, caused a shiver to run down the spines of the open and tacit supporters of the counter-revolution. At any moment the Provisional Government would be compelled ignominiously to leave the stage. Nikitin, the Minister for the Interior, communicated with the City Council for the last time. Madame Kuskova, a member of the Constitutional Democratic group in the Council, informed him that a large deputation representing all the groups in the Council was going to the Winter Palace. Powerless to render any assistance to the Provisional Government, the leaders of the petty-bourgeois parties, in conjunction with the Constitutional Democrats, resolved to organise a procession to the palace. When news of the presentation of the ultimatum to the Provisional Government reached the City Council the Mayor proposed that a deputation be sent to the Aurora to endeavour to avert the bombardment. It was also decided to send similar deputations to the Winter Palace and to the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. Included in the deputations were the Mayor, G. I. Schreider, the Chairman of the Council, A. A. Isayev, Countess Panina, Korotnyev, and others. The deputation to the Aurora was the first to return. This was about 11 p.m. The meeting of the Council was at once resumed. The deputation reported that they had not been allowed to board the cruiser. This information roused a storm of protest. Bykhovsky, a Socialist-Revolutionary, sprang to the rostrum.

“The Council cannot remain indifferent at a time when the worthy champions of the people remain alone in the Winter Palace, ready to die,” he declaimed.[1]

He concluded his hysterical outburst with the suggestion that the entire Council should march to the Winter Palace in order to die together with the elect of the people.

At this juncture, S. N. Prokopovich, a member of the Provisional Government, appeared at the meeting. In a tearful voice he complained that he had been prevented from going to the Winter Palace to share the fate of the Provisional Government. With outstretched arms he implored the Councillors to do something.

“At a time like this,” he said, “when our chosen representatives are dying, let us forget our party squabbles . . . and let us all go to defend them or die!”[2]

The meeting then adjourned to enable the groups to discuss the question as to whether they should die together with the Provisional Government. When the meeting was resumed, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks stated that they had decided to die. The Constitutional Democrats and the other groups stated that they were ready to die with the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks. The Mayor of Pyatigorsk, who happened to be at this meeting, expressed the desire to join in the procession. A member of the Saratov City Council, who also happened to be at the meeting, associated himself with the Mayor of Pyatigorsk.

The proposal to go to the Winter Palace was put to a vote by roll call. A hush fell upon the assembly. As each Councillor’s name was called he rose and answered in a solemn voice: “Yes, I will go and die together with the Provisional Government.” Sixty-two Councillors responded in this way. Fourteen stated that they preferred to join the deputation to the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies. Three Menshevik-Internationalists abstained from “dying.”

The Councillors descended the stairs to go into the street. At this juncture the deputation which had gone to the Winter Palace appeared. Everybody returned to the Council Chamber and the meeting was again resumed. The deputation reported that they had failed to reach the Winter Palace. With great difficulty they had made their way through gloomy cellars from Millionnaya Street to the Palace Square and then, displaying a white flag, they moved towards the palace. But here they were fired at from the palace. The spokesman for the deputation stated apologetically that evidently, owing to the darkness, the defenders of the Winter Palace had not noticed the white flag. One of the Councillors opined that the deputation was evidently fired at because the defenders were afraid of opening the gates to the Bolsheviks.

Countess Panina then mounted the rostrum and said excitedly:

“If the Councillors cannot get to the Winter Palace they can stand in front of the guns that are bombarding the palace and categorically declare that only over their dead bodies will the Bolsheviks be able to shoot the Provisional Government!”[3]

This exhortation raised the spirits of the Councillors and they again went into the street. A cold, drizzling rain was falling. The streets seemed deserted. Not a shot was heard. The Councillors halted irresolutely. Suddenly a “messenger” appeared.

“Wait!” he said. “The Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies in a body is on the way here to hold a joint meeting with the Council.”

Again everybody returned to the Chamber to wait for the arrival of the Soviet. The Councillors, whose spirits had been whipped up by hysteria, became despondent again. Just then it was reported that S. Maslov, the Minister for Agriculture, who was in the Winter Palace, had managed in some way to send a message. In this message, which he himself called “posthumous,” Maslov stated that “if he is destined to die, he will die with curses on his lips against democracy which had sent him to the Provisional Government, which had insisted on his going, and was now leaving him defenceless.”[4]

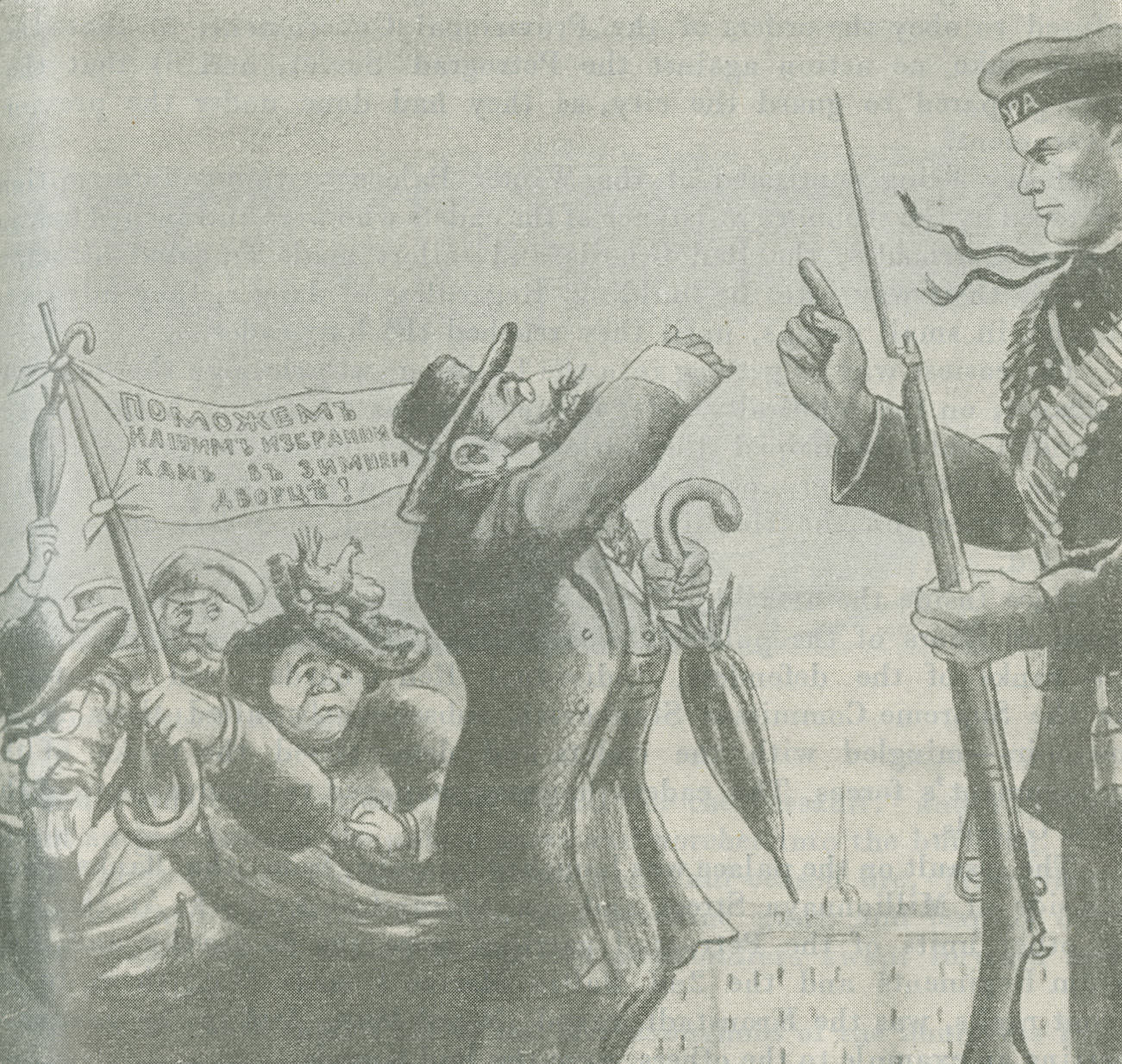

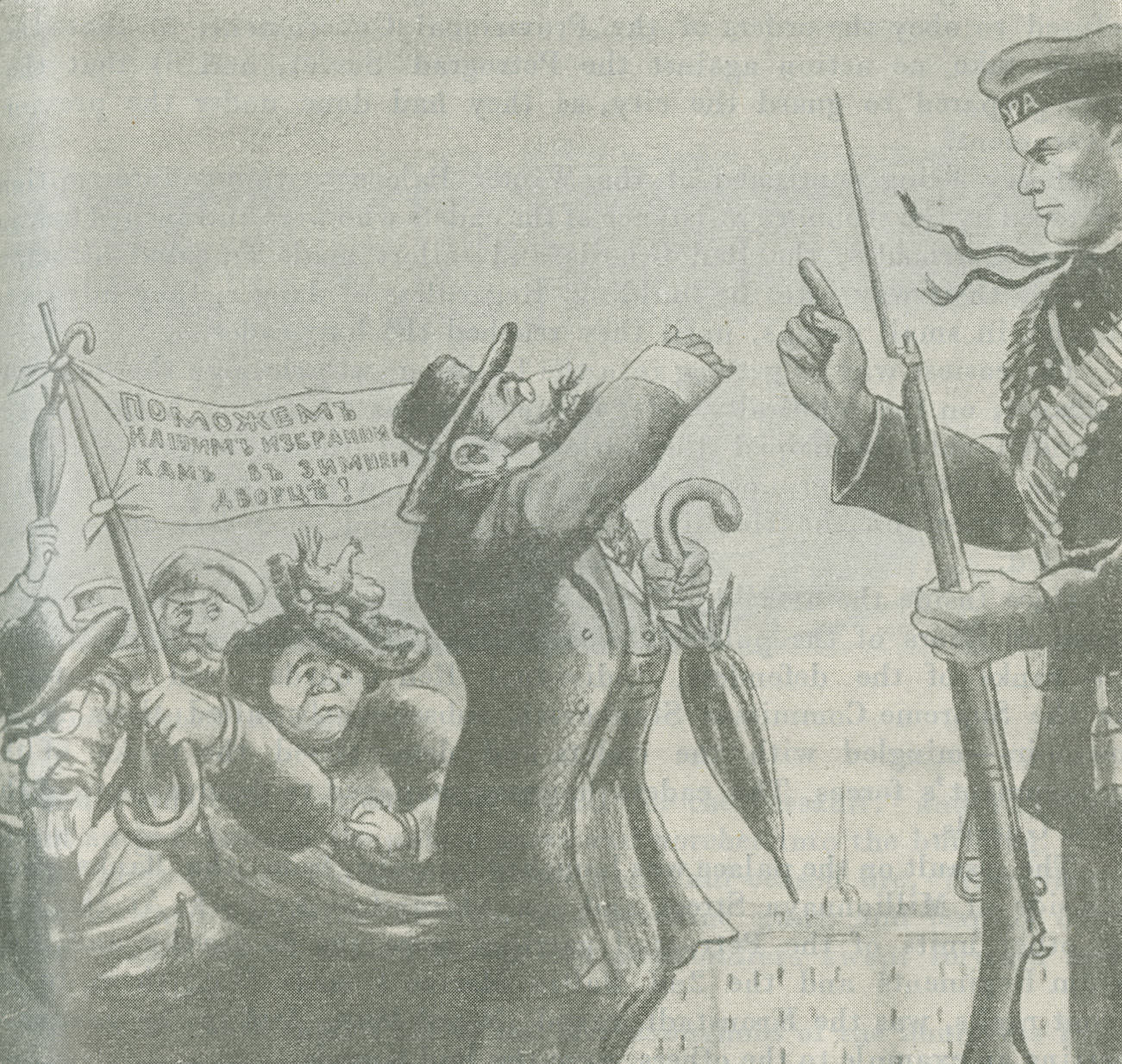

This message had a galvanizing effect. Again the Councillors began to talk about going immediately to die for the Provisional Government. Finally, late at night, they started out for the Winter Palace. The procession was headed by Mayor Schreider and by Prokopovich, who carried a lantern in one hand and an umbrella in the other. But the members of the City Council were not destined to die just yet.

The procession managed to reach the Ekaterininsky Canal. Here their road was barred by a detachment of sailors. “The Committee has given orders to allow no one to go to the Winter Palace,” they said.

Schreider and Prokopovich entered into an altercation with the sailors. Angry voices were raised in the procession. One of the sailors raised his finger and said to them sternly:

“Now go home and leave us in peace!”

The Councillors hesitated, grumbled, and then quietly returned to the City Hall. A somewhat peremptory order had been sufficient to compel these political corpses to retire.

Meanwhile, the situation at General Headquarters had undergone a sharp change. Some time between 10 p.m. and 1 a.m., General Dukhonin called up the Northern Front. General Lukirsky, Chief of Staff, replied. He reported to Dukhonin that at 10 p.m., General Cheremisov, the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front, had countermanded all the orders for the dispatch of troops. General Dukhonin ordered General Cheremisov to be called. Asked to explain his action Cheremisov stated that he had information that the old government was no longer in power in Petrograd, and that the Constitutional Democrat Kishkin had been appointed Governor-General. Kishkin’s appointment had caused a change in the attitude of the army organisations of the front that was unfavourable for the Provisional Government.

Dukhonin expressed surprise and urged the necessity of supporting the government and performing one’s duty to one’s country, but Cheremisov interrupted him and said:

“For the time being treat what I have said as confidential; but mark my word, there is no longer a Provisional Government in Petrograd.”[5]

Dukhonin communicated with the Western Front. It transpired that Cheremisov had already communicated with General Baluyev, the Commander-in-Chief of this front, who, like Dukhonin, had pleaded for unity, and had appealed to honour and duty. Cheremisov, however, had remained adamant.

General Headquarters again communicated with the Northern Front. Baluyev, in his turn, tried to communicate with Dukhonin, but the latter was busy communicating with the Winter Palace.

While the generals were in communication with each other, the news of the revolution in Petrograd spread like wildfire among the troops. The regiments refused to go into action in defence of the Provisional Government. The Cycle Battalion halted at a place 70 kilometres from the capital. The Military Revolutionary Committee sent Sergo Orjonikidze to meet them. Orjonikidze had just returned from Transcaucasia, whither the Central Committee had sent him after the Sixth Congress of the Party. On reaching the battalion, Orjonikidze arranged a meeting, and in a passionate speech told the men about the insurrection in Petrograd and revealed to them that they had been duped. The soldiers loudly applauded the speaker and placed themselves under the command of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

In the Army Committee of the Northern Front a split occurred over the question. The majority were obviously not on the side of the Provisional Government. Just at the moment when Cheremisov was in communication with General Headquarters, the committee was drawing up a resolution. The Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front was no longer master of the situation. His orders had no force whatever. In view of the temper of the rank and file, he was compelled to refrain from dispatching any troops.

In Petrograd nobody came to the aid of the Provisional Government. Even the Cossacks deserted it.

The conduct of the Cossacks most strikingly illustrates the rapidity with which the revolution demoralised the fighting forces of the counter-revolution. On October 25, the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces was in session the whole day with the Regimental Committees of the 1st, 4th and 14th Don Cossack Regiments, which were quartered in Petrograd. The representatives of these regiments stated that the Cossacks were unwilling to defend the Provisional Government, and in any case, they refused to go into action unless they were supported by infantry. The Cossack chiefs, including the newly-hatched Cossack, the Socialist-Revolutionary B. Savinkov, who had been co-opted on the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces, spent hours and hours trying to persuade the Cossacks to support Kerensky. Savinkov and Filatov, a member of the Council, promised the Cossacks that their main demands would be conceded if they supported the government. They flattered and cajoled the Cossacks, promising that their privileges would be preserved, and trying to incite them against the Bolsheviks by stating that they, the Cossacks, would be the first to suffer at their hands, that they would confiscate their land, and so forth.

Although worn out by these lengthy exhortations, the representatives of the Regimental Committees refused to take a ballot on the proposal made by the leaders of the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces and requested that the meeting be adjourned to give them an opportunity of discussing the question in their Regimental Committees. When the meeting was resumed, two regiments (the 1st and 14th) promised to obey orders; but even in these regiments several of the Hundreds insisted that the infantry must be brought out first. The 4th Don Cossack Regiment categorically refused to go into action. The Council of the Union of Cossack Forces passed a resolution in favour of supporting the Provisional Government and stated that the regiments were prepared to go into action against the insurgents.

It transpired, however, that in adopting this resolution the Council had “reckoned without its host.” In the evening, despite the decision of their Regimental Committees, all three regiments stated: 1) that they refused to obey the orders of the Provisional Government; 2) that they would take no action against the Petrograd Soviet, and 3) that they were prepared to guard the city, as they had done under the previous government.

Heavy firing continued at the Winter Palace without interruption. Irritated by the stubborn resistance of the cadets who were entrenched behind the log barricades, the Red Guards and sailors made repeated attempts to force their way into the building. Regardless of danger, they advanced slowly, in small groups, until they reached the barricades.

The easiest way of getting into the building was through the Saltykov entrance, on the Admiralty side, where there was a military hospital. The wounded soldiers helped the sailors and Red Guards to gain entrance. At the same time, groups of besiegers penetrated into the palace through the entrances on the Hermitage side, which had been left entirely unguarded.

Once inside the attacking forces quickly mounted the stairs and occupied all floors of the palace. Taking advantage of the consternation in the ranks of the defenders, individual Red Guards—“red agitators,” as the Supreme Commissar Stankevich subsequently called them in his memoirs—mingled with the cadets and demoralised the ranks of the government’s forces. The cadets however managed to disarm some of the Red Guards.

The assault on the palace was launched mainly from the flanks—from the side of Millionnaya Street and the Alexandrovsky Park. At the head of other units of the Petrograd garrison were the Pavlovsky and Kexholm Regiments and the 2nd Baltic Marine Guards. With them, in the front ranks, was the Kronstadt mixed Naval Unit. And in the vanguard, setting an example to the others, were the Red Guards.

The searchlights from the warships pierced the prevailing gloom and threw a flood of light on the palace, the walls of which gleamed scarlet, as if they had been painted with blood. From the windows of the brightly-lit rooms beams of light reached into the Palace Square. Gradually, the cadets extinguished the lights in the rooms. The rattle of rifle and machine-gun fire and the boom of guns mingled in one continuous roar.

At about 1 a.m. the fire from the barricades began to subside.

The besiegers drew closer to the palace and concentrated round the Alexander Column. Pressure from the flanks increased. The Red Guards began to gather at the wood piles, using them as a breastwork against the cadets. An order was passed down the line: “Cease fire! Wait for a single rifle shot, which will be the signal for the assault!”

Meanwhile, Red Guards who had succeeded in gaining entrance earlier were fighting inside the palace. Occasional rifle shots and the rattle of a machine gun were still heard; but the enemy was no longer able to withstand the pressure of the forces surrounding him.

Soon a rifle shot rang out—the signal for the “assault,” and a human torrent surged through the palace gates and porches into the building.

The guns of the Fortress of Peter and Paul ceased fire. Triumphant cheers drowned the rattle of rifles and machine guns, and leaping over the barricades the Red Guards, sailors and soldiers swept forward and filled the palace.

By 2 a.m. the Winter Palace, the last stronghold of the bourgeois Provisional Government had fallen.

Cheering, the tramp of thousands of feet, and the clatter of rifle butts disturbed the tranquillity of the royal apartments. For 150 years, this vast and magnificent edifice had dominated the city like an impregnable fortress, a symbol of the unshakeable power of the landed aristocracy and the bourgeoisie. But now the Petrograd workers, soldiers and sailors were complete masters of this building, which formerly had been closed to them.

The Winter Palace was completed in 1762, in the reign of Peter III. The cost of building it was met out of “tavern profits,” i.e., the revenues obtained from the taverns, which were the tsar’s monopoly. The palace was built by the famous 18th century architect, Rastrelli, who had designed the Smolny. In his memorandum to the Senate conveying the Empress Elizabeth’s request for funds with which to build the palace, Rastrelli stated:

“The stone edifice of the Winter Palace is being built solely for the glory of Russia.”[6]

The massive columns of the Imperial Palace proudly reared their heads in the great Palace Square. The gilded coaches of the courtiers rolled up to its porches, while the ragged workmen of the city, furtively passing beneath its glittering windows, were bawled at by the guards, ordering the “common herd” to keep at a respectful distance.

In the winter of 1837 the palace was gutted by fire, but it was restored by order of Nicholas I with even greater pomp and splendour. Scaffolding was immediately erected around the ruins of the burned-out palace and 6,000 craftsmen were rounded up from all parts of Russia to rebuild it. Work went on day and night, amidst the biting frost of winter. Inside, in the halls, the temperature was as high as 30° Centigrade, to such an extent were the stoves heated to dry the walls more quickly. The wall painters were obliged to wear special caps with ice to cool their heads, for it was impossible to work in the heat otherwise. Scores of workers died as a result of the unbearable conditions of labour, but the palace was rebuilt in little over a year.

The new palace was an imposing building. Within, a series of vast and magnificent halls, decorated with dazzling splendour and luxuriously furnished, led to the royal apartments.

The keynote of its architectural design was the triumph of the autocracy. Nicholas I issued an ukase prohibiting the erection in St. Petersburg of any building higher than 22 metres, i.e., higher than the Winter Palace. Several years earlier, in 1834, the tsar had erected in the Palace Square the Alexander Column, a granite pillar, 25 metres high, surmounted by the figure of an angel with a cross, trampling upon the serpent of revolution. Looking at it from the pavement the angel appeared to be standing in front of the windows of the tsar’s palace like a sentry presenting arms.

The base of this granite palace stronghold was washed by the tears of grief and anger of the people. More than once the tide of popular wrath surged beneath the windows of the royal apartments; and it was in this Palace Square that the revolutionary soldiers were lined up in December 1825. In one of the halls of the palace, Nicholas himself interrogated the insurgent officers, late at night, with the blinds tightly drawn. It was to the Winter Palace that the workers of St. Petersburg came with icons and portraits of the tsar to petition the “little father” on that memorable frosty day of January 9, 1905. The Winter Palace greeted them with a hail of bullets; its granite and marble walls were bespattered with the blood of the workers, their wives and children.

After the July days in 1917, the Provisional Government, celebrating its victory over the Bolsheviks, removed to the Winter Palace. The “Socialist” Minister, Kerensky, took up his abode in the apartments of Alexander III. The only change witnessed in the royal apartments and halls of the Winter Palace was the change of inmates. It was only on the night of October 25 (November 7), 1917, that this ancient stronghold of landlord and capitalist rule finally fell. The new rulers of the country—the workers and soldiers—mounted the 117 marble steps of the grand staircase. One after another, all the 1,786 doors were flung open before them, and the heavy tread of the Red Guards re-echoed in each of its 1,050 chambers and halls.

The Red Guards, sailors and soldiers swept into the palace like a torrent and disarmed the cadets who were benumbed with fear.

“Provocateurs! Kornilovites! Murderers of the people!” were the epithets hurled at them on all sides. Nevertheless, not one of them suffered harm.

In a large ante-chamber, guarding the hall in which the Provisional Government had taken refuge, a number of cadets stood stiffly with their rifles at the ready. This was the last group of defenders of the Provisional Government. Their weapons were torn out of their hands.

Palchinsky burst into the hall to meet the invaders, shouting that an agreement had been reached and that a deputation representing the City Council and the Soviet were on their way to the palace. He was placed under arrest. The hall in which the Provisional Government was hiding was immediately occupied by the revolutionary forces. The Ministers, who were found standing, pale and confused, were likewise placed under arrest. “Why bother with them? They have sucked our blood long enough!” shouted a hefty sailor, stamping his rifle on the floor.[7] The other men calmed the sailor. The Military Revolutionary Committee is in command, they explained. There must be no unauthorised action.

Amidst solemn silence a list of the arrested Ministers was drawn up, after which they were led out. Every Minister was called by name and then ordered to proceed with an armed soldier behind him. In this way a living chain was formed, which moved along the half-lit corridors to the exit. Crowds of Red Guards, sailors and soldiers filled the dark, damp square.

“Where’s Kerensky?”—they asked.

On learning that the Prime Minister had fled, they poured curses on his head, and declared their determination to catch him.

The “creatures that once were men,” were led under escort to the Fortress of Peter and Paul.

With the fall of the Winter Palace, the power of the Provisional Government was utterly liquidated. The great proletarian revolution had triumphed in the capital.

[1] “The City Duma,” Rech, No. 252, October 26, 1917.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Documents,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. VII, Berlin, 1922, p. 299.

[6] N. V. Kukolnik, “The Erection of the Winter Palace in the Reign of the Empress Elizabeth (1753-1762),” Russki Vestnik. (Russian Messenger), St. Petersburg, 1841, Vol. IV, p. 15.

[7] P. N. Malyantovich, Revolution and Justice (Several Thoughts and Recollections), Zadruga Publishers, Moscow, 1918, p. 215.

Previous: The Siege of the Winter Palace

Next: The October Insurrection—A Classical Example of a Victorious Proletarian Insurrection