The ring around the Winter Palace was drawing ever tighter:

At 5 p.m. on October 25, the Red Guards, fighting their way through, approached the palace.

Situated on the Neva embankment the Winter Palace is a huge, three-storey building, nearly two hundred metres long, 160 metres wide and 22 metres high. Together with the adjacent Hermitage and the Hermitage Theatre, it occupies an area of nearly nine hectares. The palace is fronted by a large square, flanked on both sides by the huge buildings of the General Staff and the Admiralty. In the middle of the square the Alexander Column reared its lonely head.

The forces of the Military Revolutionary Committee held all the streets leading into the Palace Square. On the right, near the Guards Headquarters and the Pevchesky Bridge, units of the Red Guard and of the Ismailovsky Regiment were concentrated. The Pavlovsky Regiment and small groups of men of the Preobrazhensky Regiment advanced along Millionnaya Street, which led to the Guards Headquarters, to the Zimnaya Kanava—the narrow canal which flows into the Neva between the palace and the Hermitage. The Reval Shock Battalion of sailors took up positions along the Neva, on the Peter the Great Embankment, and in the vicinity of the Troitsky Bridge.

Opposite the Winter Palace, behind the General Staff building in Morskaya Street, and in the streets adjacent to it and near the Politseisky Bridge, a strong force was concentrated, consisting of units of the Red Guard from the Vyborg and Petrograd Districts. Here, too, were stationed the Armoured Car Detachment, the anti-aircraft guns, and a half-battery of field artillery. Further along the Neva, near the Kazan Cathedral, heavy guns were placed ready for action. These guns had been transferred from the front by the Provisional Government, but on their arrival in the capital the crews went over to the side of the Petrograd Soviet.

In the Alexandrovsky Park, near the General Staff buildings, were stationed units of the Red Guard, sailors from the Kronstadt Naval Torpedo School, men from the Second Baltic and Guard Marines, men of the Kexholm Regiment, and some armoured cars.

On the left, near the Admiralty, were sailors from the Naval Engineers’ School, from the training ship Okean, and other units from Kronstadt. Moreover, the left flank and the centre were supported by reserves of the Chasseur and Volhynia Regiments.

On the opposite bank of the Neva were concentrated workers’ units from the factories in the Vasilyevsky Island District. Vasilyevsky Island was connected with the centre by the Palace Bridge, the approaches to which were controlled by Red Guards.

On the other side of the river, opposite the Winter Palace, the slender spire of the Fortress of Peter and Paul loomed high in the gathering twilight. The fortress, too, was preparing to take an active part in the battle.

The Fortress of Peter and Paul was the first structure to be erected in this area and is the most ancient in Petrograd. It was built by Peter the Great on the small Jenisaari Island (Hare Island), on the Neva, and was completed in 1703. Over 60,000 serfs and soldiers perished in the course of building this first stronghold of the autocracy on the banks of the Neva. Subsequently, the fortress was converted into a state prison. In the cathedral within the fortress, a mausoleum for the tsars of Russia was built, and near the pompous tombs of tyrants, in the damp, stone cellars of the fortress ravelins, the finest representatives of the Russian people—the revolutionaries—were confined in living graves. Now the fortress trained the muzzles of its guns upon the Winter Palace—the last stronghold of the tsarist regime.

The Military Revolutionary Committee drew up its final plan of operations. It was resolved to send an ultimatum to the Provisional Government, calling for surrender not later than 6:20 p.m. If it refused the fortress was to fire a gun. The cruiser Aurora was to fire two blank shots from one of its 6-inch guns, which were to serve as the signal for storming the Winter Palace.

Volunteers were called for to convey the ultimatum to the Winter Palace. This was undertaken by V. Frolov, of the 1st Cycle Battalion.

The ultimatum was hastily typed. In it, the Military Revolutionary Committee called upon the Provisional Government to surrender the Winter Palace and the Headquarters of the Petrograd Military Area, failing which these buildings would be bombarded. The Fortress of Peter and Paul and the cruiser Aurora were ready to open fire.

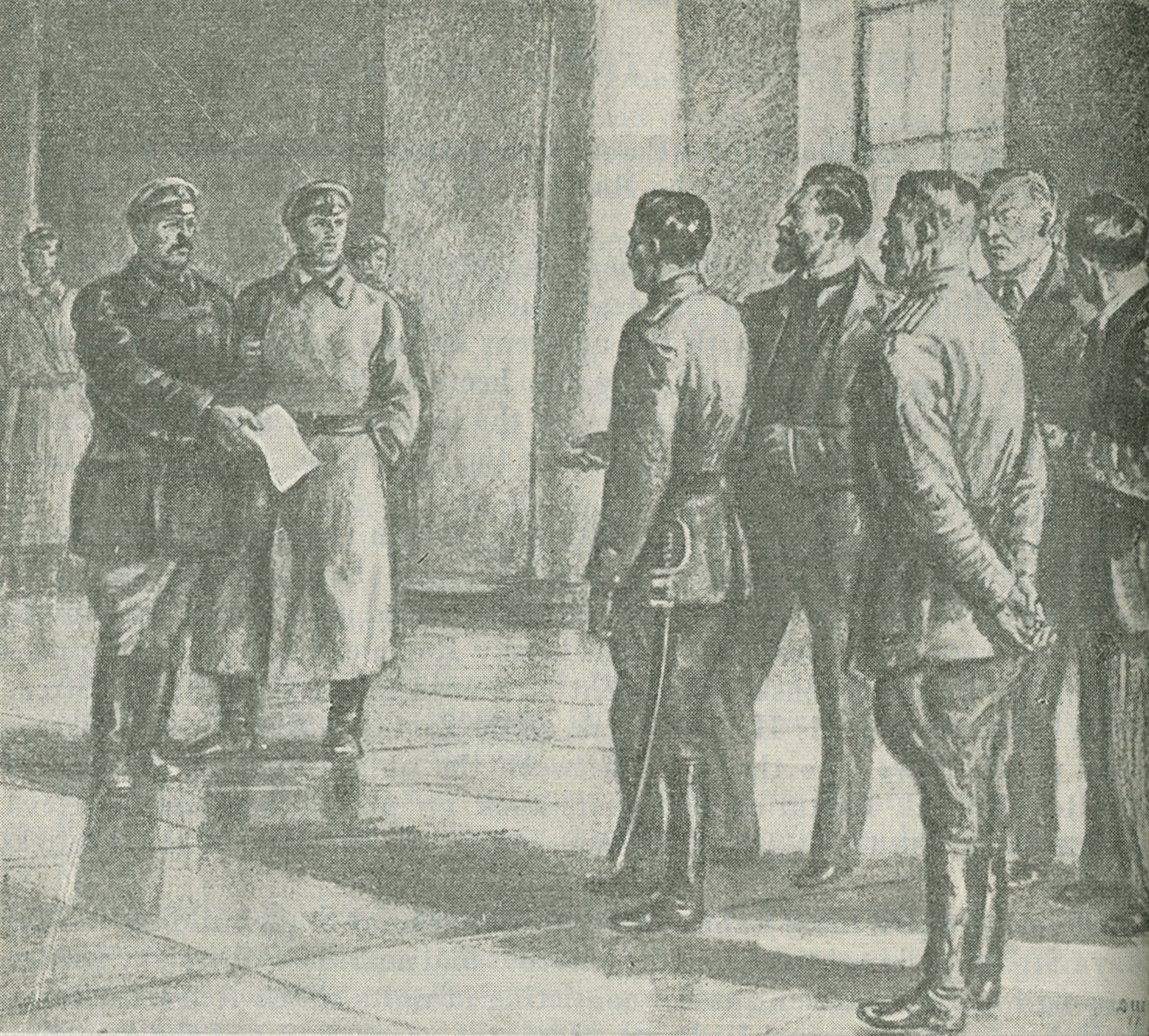

Accompanied by another cyclist named A. Galanin, Frolov set out for the Winter Palace. Near the Hermitage they were stopped by the Red Guard cordon, but after explaining their mission they were allowed to pass. Carrying a white flag they advanced towards the enemy positions. Three cadets, with rifles at the ready, came out to meet them. The emissaries requested to be taken to Headquarters to present the ultimatum.

One of the cadets said threateningly: “I’ll give you ultimatum!” Nevertheless, Frolov was taken to Headquarters. There he found N. M. Kishkin, member of the Provisional Government and the Minister responsible for restoring order in Petrograd, together with his two deputies P. Palchinsky and P. Ruthenberg. General Bagratuni and Lieutenant-Colonel N. N. Poradelov were also present. “Twenty minutes for reflection,” said Frolov, handing over the ultimatum. Kishkin, accompanied by his assistants and General Bagratuni, went to the Winter Palace, promising to reply by telephone.

The members of the government were informed of the receipt of the ultimatum.

The Provisional Government was assembled in the Malachite Hall, the enormous windows of which looked out on the Neva. The Ministers perused the terse, stern terms of the ultimatum, and then gazed across the river. From a corner window they could see the grim outlines of the Aurora anchored off the bridge. On the other side of the river they saw mysterious lights shining from the Fortress of Peter and Paul. Surrender or wait for assistance? The government decided to consult General Headquarters before replying to the ultimatum.

The Central Telegraph Office had long been in the hands of the revolutionaries and it was believed that the connections of the Winter Palace had been cut; but this was not the case. One line had remained undiscovered, probably that of the Ministry of Railways, or the War Ministry. Availing themselves of this wire the Provisional Government maintained direct communication with General Headquarters till the very last minute. The Menshevik Nikitin went to speak with General Headquarters from whom he received precise information as to which regiments had been sent to the aid of the Winter Palace.

The Provisional Government thereupon decided not to enter into negotiations with the Military Revolutionary Committee.

Twenty minutes elapsed. The emissaries demanded the answer which had been promised. Poradelov requested them to wait another ten minutes, promising to obtain a reply from the Winter Palace. He telephoned, but received no answer. While Poradelov was telephoning the Ministers, the messengers left the palace and called a patrol of the Pavlovsky Regiment and a detachment of Red Guards. This mixed detachment entered the Military Area Headquarters, disarmed the cadets, and arrested Poradelov and a group of staff officers and dispatched them to the Fortress of Peter and Paul.

The capture of Military Area Headquarters closed the ring around the Winter Palace. The forces of the Military Revolutionary Committee took up their positions for an immediate assault upon the palace.

In the meantime, while waiting for the return of the messengers, the Fortress of Peter and Paul made preparations to open fire on the palace. The fortress artillerymen, however, refused to man the guns. The shells were unsuitable, they said in excuse; there was no grease, the guns were only fit for firing salutes.

The representatives of the Military Revolutionary Committee immediately reported this to Sverdlov by telephone, adding that the fortress artillerymen were obviously unreliable. Sverdlov immediately ordered a detachment of naval gunners from the Naval Gunnery Practice Grounds to go to the fortress.

Night was falling. While the guns were being got ready the rumour was spread in the fortress that the Provisional Government had accepted the ultimatum. Arrangements were made to receive the arrested Ministers.

From the direction of the Winter Palace, however, the sound of machine-gun fire was heard. Podvoisky and Yeremeyev, members of the Military Revolutionary Committee, hastened to the palace in a car. Near the Zimnaya Kanava they were stopped by Red Guards and in answer to their queries they explained who they were and where they were going, stating that information had been received of the surrender of the palace. At this, one of the Red Guards said scornfully:

“Who surrendered? There was pretty hot firing from that quarter just now. It’s dangerous to go there.”

It turned out that only Military Area Headquarters had been captured. The Winter Palace was still resisting.

Nikitin, the Minister for the Interior, rang up Khizhnyakov the Vice-Minister, informed him about the ultimatum and requested him to intimate to all public organisations that the government demanded their full support. He assured Khizhnyakov that if small units were dispatched in the rear of the forces surrounding the Winter Palace the besiegers would disperse. Khizhnyakov went to the City Council and made enquiries of all the parties represented in it. The Constitutional Democrats, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks promised to support the government.

Nikitin again telephoned Rudnyev, the Mayor of Moscow, and informed him of the government’s decision to defend itself.

“Quite right,” replied Rudnyev, adding that Moscow had followed Petrograd’s example and had decided to establish a “Committee of Public Safety.”

“That is not enough,” said Nikitin, interrupting him. “The question of power must be put point-blank. If you share the point of view of the Provisional Government you must appeal to the whole of Russia.”

Rudnyev promised to carry out the government’s instructions forthwith.[1]

At General Headquarters forces were being feverishly mustered. The telegram of the Military Revolutionary Committee announcing the insurrection was kept back from the army. Only the Commanders-in-Chief of the different fronts were informed of it, and they passed this information on to their Army Committees. At 6 p.m. on October 25, General Headquarters received telegraphic reports from the Army Committees on the reaction to events in Petrograd.

The Executive Committee of the Rumanian Front, the Black Sea Fleet and the Odessa Military Area (the Rumcherod) stated that it had sufficient forces at its disposal to liquidate the insurrection.

The Chairman of the Executive Committee of the South-Western Front declared that seizure of power by force of arms was impermissible, and promised to send a resolution of the entire Committee to that effect.

Members of the Executive Committee of the Western Front firmly expressed the opinion that the Committee would support General Headquarters, adding however, that the feeling of the Second Army had not yet been ascertained.

The Executive Committee of the Northern Front reported that apparently the Twelfth Army condemned the Bolsheviks, but added that the Bolsheviks might find support in the Fifth Army. Similar reports were received from the units in the rear of the Northern Front.

Thus, the nearer the units were to the revolutionary capital, the more hesitant were the replies from the Army Committees. The Rumanian Front unreservedly expressed readiness to suppress the insurrection. The Northern Front relied only on one of its armies. This was not surprising. While the Front Committee was communicating with General Headquarters, the Fifth Army called up the Military Revolutionary Committee in Petrograd and asked: “Do you need any military assistance and provisions?”[2] The Committee answered that assistance was not needed at the moment, but requested the army to prepare for action.

About 7 p.m., immediately after the capture of Military Area Headquarters, General Headquarters communicated with the Winter Palace. Lieutenant Danilevich, Kerensky’s adjutant, conveyed to Headquarters the following telegram on behalf of Konovalov, Kerensky’s deputy:

“The Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies has proclaimed the overthrow of the government and has demanded the surrender of power, threatening that if this was not complied with the Fortress of Peter and Paul and the cruiser Aurora would bombard the Winter Palace. The government can surrender power only to the Constituent Assembly. It has decided not to surrender, and to place itself under the protection of the people and the army. Expedite the dispatch of troops.”[3]

General Headquarters replied that Cycle Battalions should arrive in Petrograd that day, October 25. The 9th and 10th Don Regiments with artillery, and two regiments of the 5th Caucasian Division would arrive in the morning of the 26th; the 23rd Don Regiment would arrive in the evening of the 26th; the remaining regiments of the Caucasian Division would arrive in the morning of the 28th, and a brigade of the 44th Division with two batteries would arrive in the afternoon of the 30th. Headquarters expressed the assurance that the Winter Palace would succeed in organising its defence and hold out until the arrival of the troops from the front.

The government decided to continue its resistance. The cadets of the Oranienbaum and Peterhof Military Schools were assembled in the White Hall of the Winter Palace, where Palchinsky addressed them. The cadets listened in gloomy silence. Palchinsky loudly called upon them to perform their duty. “We shall perform it,” came the response,[4] but it was none too hearty, and far from unanimous.

A cadet of the Petrograd Engineer Corps Training School, who with his fellow cadets had been called to the Winter Palace in the afternoon of October 25, related the following:

“The object of our presence in the palace was not clear to us. We were excited and wanted to talk to the other cadets (the Mikhailovs, Northern Front, and others), but we were not permitted to do so. At last, an hour or two later, we were told that everything would be explained, and we were ordered to line up in the courtyard. It was already quite dark. We lined up. Somebody came along who introduced himself as Governor-General Palchinsky and delivered a long harangue. His speech was jerky and disjointed. He said that we must defend the Provisional Government, perform our duty, and so forth.”[5]

To rouse the spirits of the cadets Palchinsky told a deliberate lie. He said:

“Kerensky and the troops are already in Luga, only about 40 versts from Petrograd.”

The cadets remained silent. Suddenly, the silence was broken by one of them, who said in a dour, ironical voice:

“You would have done well to have consulted a railway guide before telling us how many versts it really is from Luga to Petrograd.”

Actually Luga is about 140 versts, or kilometres, from Petrograd.

Murmurs of discontent were heard on all sides. The speaker was bombarded with questions and commotion became rife. Palchinsky barely managed to get away.

The garrison of the Winter Palace began to waver. Malyantovich, the Minister for Justice, who was kicking his heels in the palace with the other members of the Provisional Government, subsequently related the following:

“We were informed that the cadets wished to see the members of the Provisional Government. This request was couched in very insistent terms. . . . The very fact that such a request should be made showed that the cadets were wavering. . . . We went out to speak to them. We found a hundred or more cadets assembled in the lobby.

“What military orders could we give them? None,” concluded Malyantovich gloomily.[6]

The members of the government confined themselves to making pitiful appeals to the cadets, which merely served the latter as topics for discussion. They were extricated from this embarrassing position by the hasty arrival of the “dictator” Kishkin with the information that the Military Revolutionary Committee had presented an ultimatum demanding surrender within twenty minutes. Malyantovich goes on to relate the following:

“Palchinsky came in and reported that the Cossacks wished to speak with the Provisional Government. Two officers, one of them of high rank, had arrived with this request.

“They were invited to enter.

“A Cossack officer, a colonel, I think, entered, accompanied by another officer.

“They inquired what the Provisional Government’s intentions were.

“Kishkin and Konovalov answered. We stood around. Now and then one or another of us put in a word.

“We told them what we had already told the cadets.

“The colonel listened attentively, now raising and now dropping his head. He put several questions. At the end of the conversation he raised his head. He had been listening out of politeness. He did not utter a word. He heaved a sigh, and both officers left—it seemed to me with a puzzled look in their eyes . . . or, perhaps, with their minds made up.

“A little later Palchinsky returned with the news that the Cossacks had left the palace, saying that they did not know what they had to do there.”[7]

The demoralisation of the Provisional Government spread to its defenders. After the departure of the 300 Cossacks, who left the palace in spite of the government’s exhortations to them to remain, other units followed suit. At 6 p.m. the majority of the cadets of the Mikhailovsky Artillery School left, taking with them four of the six guns that were in the palace. They were held up by the revolutionary forces on the Nevsky Prospect. At 8 p.m., Chudnovsky, a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee, was invited by a delegate of the Oranienbaum School to open negotiations for the surrender of the cadets, who had no desire to fight on the side of the Provisional Government. The cadets guaranteed Chudnovsky safe conduct and kept their word, but Palchinsky had him arrested. When the cadets heard of this they at once protested and Chudnovsky was promptly released. The majority of the cadets of the Oranienbaum School and those of several other schools left the palace with him.

In the palace there remained 310 cadets of the 2nd Peterhof Officers’ Training School, 352 cadets of the 2nd Oranienbaum Officers’ Training School with nine machine guns, a company of the 1st Petrograd Women’s Battalion, 130 strong, a company of cadets from the Engineers’ School, the cadets of the Officers’ Training School of the Northern Front, one armoured car, the Akhtyrets, two machine guns and two field guns. In addition, there were 50 or 60 nondescript military men in the courtyard. This force, numbering in all about 850 men, was well armed. The armoured car was stationed at the main gate. Outside the palace, barricades of logs collected there for firewood had been built in order to hinder the approach of the attackers. Machine guns and field guns were mounted behind the barricades covering the Palace Square and the adjacent streets.

Artillery, evidently from Pavlovsk, were moving to the assistance of the Winter Palace. The batteries advanced without forward patrols, evidently not expecting an attack in the city. In Morskaya Street, the Red Guards lay in ambush for them at the entrances to the courtyards of the houses lining the street. When the artillery drew level with them the Red Guards suddenly attacked and disarmed them. The attack was so swift that no resistance was offered. The guns were captured and immediately trained on the Winter Palace.

The Red Guards made a dash for the palace and about fifty of them, supported by sailors, forced their way into the building through the Hermitage entrance. The unusual surroundings, the plush and gold decorations, amazed the men. For a moment they were overawed. Then they began cautiously to mount the staircase. A Red Guard opened the door of one of the halls. In a huge mirror he saw the reflection of a painting depicting a cavalry parade. “Cavalry!” he exclaimed, and dodged to one side. Taking advantage of the confusion that ensued, the cadets disarmed a number of the invaders. The rest rushed down the stairs. The palace servants and the soldiers in the hospital situated below, helped them to escape from the labyrinth of rooms and corridors of the palace. Palchinsky commented to himself bitterly: “All the doors are open. The servants are helping. Slaves! The men too!”[8]

[1] “A. M. Nikitin’s Story,” Rabochaya Gazeta, No. 198, October 28, 1917.

[2] “The Front,” Novaya Zhizn, No. 164, October 27, 1917.

[3] Central Archives of Military History, The Fund of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, Quartermaster-General’s Administration, File No. 813, folio 41.

[4] “The Last Hours of the Provisional Government in 1917,” Krasny Arkhiv, 1933, Vol. I (56), p. 137.

[5] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1052, File No. 343, 1917.

[6] P. N. Malyantovich, Revolution and Justice (Several Thoughts and Recollections), Zadruga Publishers, Moscow 1918, pp. 202-204.

[7] Ibid., pp. 208-209.

[8] “The Last Hours of the Provisional Government in 1917,” Krasny Arkhiv, 1933, Vol. I (56), p. 137.

Previous: October 25 (November 7)—The First Day of the Victorious Socialist Revolution

Next: Capture of the Winter Palace