The first thing to be done was to secure additional forces, for the enemy was concentrating fresh troops in the capital. The Red Guard had to be increased. A considerable section of the garrison had to be prepared for action, for it would have been unsafe to rely only on a few regiments. Lastly, it was necessary to revise the plan of the armed insurrection, for it was very probable that some of its details had become known to the enemy.

The job of carrying out the decisions of the Central Committee was entrusted to the Military Revolutionary Committee, the moving spirit of which was the Party Centre headed by Stalin which had been elected by the Central Committee.

Under the direction of this centre, the Military Revolutionary Committee became the General Staff of the armed insurrection. It quickly concentrated in its hands the contacts with all the units of the garrison and guided the operations of the Red Guard, which was the main fighting force of the insurrection.

The prestige of the Military Revolutionary Committee among the troops increased day by day and its instructions soon acquired the force of military orders. On October 18, the day on which the treacherous letter of Zinoviev and Kamenev was published, a meeting of representatives of Regimental and Company Committees of the Petrograd garrison was held in the Smolny Institute. A large number of representatives were assembled from most of the military units in and around the city. The first speaker, the representative of the Ismailovsky Regiment, said that the men of his regiment were hostile to the Provisional Government and reposed confidence only in the Soviet. They were ready to go into action as soon as the order was given.

The representative of the Chasseur Guards Regiment said that his men would come out in an organised manner on the order of the Petrograd Soviet and would demand the immediate overthrow of the Provisional Government.

The representative of the Moscow Regiment declared that his regiment had confidence only in the Petrograd Soviet and was waiting for the order to take armed action.

The representatives of the Pavlovsky Regiment and the Volhynia and Grenadier Reserve Regiments stated that their regiments would support the Petrograd Soviet by every means in their power, including organised action.

The delegate of the Kexholm Regiment read a resolution of no confidence in the Provisional Government.

The representative of the Semyonovsky Regiment described a meeting in his regiment at which the Menshevik Skobelev and the Socialist-Revolutionary Gotz had been refused a hearing. The men, he said, demanded that power should be transferred to the Soviets.

The representatives of the Guards Reserve Crews and the 2nd Baltic Reserve Crews assured the meeting that the sailors were only waiting for the order of the Petrograd Soviet to go into action.

Even the delegates of the cadet schools, such as the 2nd Oranienbaum Officers’ Training School and the 1st Petrograd Infantry School, dared not express confidence in the Provisional Government. The cadets stated that they would come out only on the order of the Central Executive Committee of Soviets.

A resolution pledging unreserved support to the Military Revolutionary Committee was carried by an overwhelming majority. The Menshevik and Socialist-Revolutionary members of the Central Executive Committee were refused a hearing, and the only thing that they could do was ignominiously to leave the meeting, declaring it to be “unauthorised.”

The meeting also decided on measures to ensure permanent communication between the Military Revolutionary Committee and the units of the garrison. It was decided to have men constantly on duty at the regimental telephones, that each unit should send two liaison officers to the Smolny, and that the Military Revolutionary Committee should issue daily reports to the regiments.

Next day the compromising Central Executive Committee of Soviets called a conference of representatives of the garrison to counteract the Bolshevik meeting.

At this conference the Menshevik F. Dan who spoke on the current situation and on the forthcoming Congress of Soviets, was given a frigid reception. It was obvious from the interruptions and jeers of the soldiers that a storm was brewing.

Dan grew more and more excited as he spoke, and at last, adopting a threatening tone, he said:

“If the Petrograd garrison responds to the call for action in the streets of Petrograd for the purpose of transferring power to the Soviets then, undoubtedly, there will be a repetition of the events of July 3 to 5.”[1]

This threat precipitated the storm. The soldiers had not forgotten the part the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks had played in breaking up the July demonstration and one after another the representatives from the different regiments rose and demanded the transfer of power to the Soviets. A number of speakers passionately appealed for an immediate armistice and the transfer of the land to the peasants.

The conference took particular exception to Dan’s statement to the effect that the convocation of the Congress of Soviets was premature. The soldiers fiercely attacked him on this point and bluntly accused the Mensheviks of wanting to sabotage the Congress.

The attempt of the compromisers to discredit the meeting of representatives of the garrison held the previous day failed completely. More than that, the conference resolved that since this particular gathering of the representatives had been convened by the Central Executive Committee without the knowledge and consent of the military organisation of the Petrograd Soviet, it had no authority to adopt any decisions. The garrison solidly backed the Military Revolutionary Committee.

In addition to members of the Petrograd Soviet and delegates of the garrison, the Military Revolutionary Committee consisted of representatives of the Central Committee of the Baltic Fleet, the Finland Regional Committee of Soviets, municipal bodies, factory committees and trade unions, Party and military organisations, and similar bodies.

At the first full meeting of the Military Revolutionary Committee held on October 20, a report was made on the Committee’s main functions. After this it was decided to establish contact with the army units in the districts and suburbs, and also to take measures to protect Petrograd from likely disorders, as the churches had arranged for a religious procession of the Cossacks for October 22. Speakers were sent to all the districts. It was resolved to issue a manifesto to the Cossacks explaining to them the political significance of the manoeuvres of the counter-revolutionaries.

From various parts of the city the Committee began to receive information testifying to the vigilance of the masses and their readiness to defend the revolution. The workers at one printing plant reported that their firm had received an order to print a manifesto issued by a Black Hundred organisation. The Committee, in conjunction with the Printers’ Union, immediately instructed the workers at this plant to refrain from fulfilling any orders without their sanction.

The workers and office employees at the Kronwerk Arsenal, in the Fortress of Peter and Paul, reported that the government was removing arms from the arsenal to supply the cadet units in Petrograd and its environs, and that it was intended to dispatch 10,000 rifles to Novocherkassk in the Don Region. Upon receipt of this information the Military Revolutionary Committee immediately appointed a Commissar over the arsenal and instructed him to stop the issue of arms to the cadets and to hold up the 10,000 rifles intended for Novocherkassk. When the commandant of the arsenal prevented the Commissar from discharging his duties the latter appealed to the workers and soldiers. Several impromptu meetings were held at which the workers and soldiers insisted that the Commissar be allowed to perform his duties and, secure in their loyalty and support, the Commissar seated himself in the commandant’s office and gave orders that no arms were to be issued without his sanction. The Military Revolutionary Committee sent its representatives to all other arms depots in the city.

On the night of October 20, the Military Revolutionary Committee appointed Commissars to all the units of the Petrograd garrison. These Commissars strengthened the influence of the Military Revolutionary Committee among the troops and improved the links between Headquarters and the masses, thus enabling it to exercise direct control of the military operations.

From the very outset, the Commissars, as the representatives of the nascent new government, encountered the resistance of nearly all the army officers, but they gained the upper hand, thanks to the whole-hearted support they received from the overwhelming majority of the soldiers, and to the tremendous work that had been carried on among the units of the Petrograd garrison by the military organisation of the Bolshevik Party.

On October 21, the Military Revolutionary Committee called a meeting of representatives of the Petrograd garrison, who once again expressed their complete confidence in the Military Revolutionary Committee and demanded that the All-Russian Congress of Soviets should take power and ensure the people peace, land and bread. In its resolution the meeting stated:

“The Petrograd garrison gives its solemn pledge to the All-Russian Congress that in the struggle for these demands it will place at their command all its forces to the very last man. . . . We are at our posts, ready for battle.”[2]

That same day the Military Revolutionary Committee set up a Bureau, consisting of three Bolsheviks and two “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries. The Bureau appointed three comrades as Commissars at the Staff Headquarters of the Petrograd Military Area and instructed them to take over control of the garrison.

That night the newly appointed Commissars presented themselves to Colonel Polkovnikov, the Commander-in-Chief of the Military Area, and informed him that henceforth all the orders had to be submitted to them for their sanction. Polkovnikov categorically refused to acquiesce to this.

On the morning of October 22, a special meeting of the representatives of all the regiments in the garrison was held in the Smolny at which a member of the Military Revolutionary Committee reported on the negotiations with Polkovnikov. The meeting adopted a resolution which contained a full account of the negotiations and noted the refusal of Headquarters of the Military Area to recognise the Military Revolutionary Committee. It declared that no orders issued to the garrison would be carried out unless countersigned by the Military Revolutionary Committee and denounced Staff Headquarters of the Petrograd Military Area, which had isolated itself from the garrison of the capital, as a tool of the counter-revolutionary forces. The resolution ended with the call:

“Soldiers of Petrograd!

“1. The duty of maintaining revolutionary order in the face of counter-revolutionary attempts to disturb the peace rests upon you, under the leadership of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

“2. No orders issued to the garrison shall be valid unless countersigned by the Military Revolutionary Committee.

“3. All the orders issued today—the Day of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies—remain in full force.

“4. It is the duty of every soldier of the garrison to be vigilant, staunch and absolutely disciplined.

“5. The revolution is in danger.

“Long live the revolutionary garrison!”[3]

While this meeting was in progress at the Smolny, Headquarters Staff of the Petrograd Military Area attempted to address the garrison over the head of the Military Revolutionary Committee. Polkovnikov summoned to Headquarters the representatives of the Regimental and Brigade Committees, and also representatives of the Central Executive Committee and of the Petrograd Soviet. The representatives of the Regimental Committees failed to appear, they were attending the meeting in the Smolny.

Polkovnikov then requested the garrison meeting in the Smolny to send representatives to his conference. The garrison meeting responded by sending a delegation to Headquarters with the instruction to inform the Staff that henceforth all the orders issued had to be countersigned by the Military Revolutionary Committee. The spokesman of the delegation delivered this message, and adding that this was all he had been authorised to say, he forthwith returned with the rest of the delegation to the Smolny.

Staff Headquarters were able to convince themselves of the power wielded by the Military Revolutionary Committee that very day. Not a single arms depot would issue arms to the Staff. All the orders issued by the Staff were returned, as they had not been countersigned by the Committee.

All day on October 22, signs of the approaching climax were visibly accumulating.

For the purpose of mobilising the workers, the Bolshevik Party had proclaimed October 22 as “Petrograd Soviet Day.” The counter-revolutionaries had arranged for a religious procession of the Cossacks on the same day. Government agents went among the Cossack regiments whispering to the men that the Bolsheviks had deliberately chosen October 22 for their “Soviet Day” in order to outrage the religious sentiments of the faithful. Shady characters tried to incite the Cossacks against the soldiers of the garrison. Counter-revolutionary sermons were preached in the churches.

The Provisional Government was anxious to pit its strength against the forces of the revolution, but at the very last moment the government’s Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik accomplices showed the white feather and advised the government to call off the religious procession.

Already on October 21 the Commander-in-Chief of the Petrograd Military Area had ordered the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces to abandon the religious procession on the grounds that it might serve as the occasion for an armed insurrection. To this, A. N. Grekov, the Cossack Hetman replied that the Cossacks would not abandon the procession, and added that the procession had been arranged by the regiments and the Council of the Union of Cossack Forces had no power to cancel their decision.

The Cossack leaders were obviously intent on provoking a conflict, but the issue was decided by the rank-and-file Cossacks. At a garrison meeting of Regimental Committees held on the evening of October 21, the representative of the 4th Cossack Regiment stated that his regiment would not take part in the procession despite the efforts of the regimental chaplain to persuade the men to do so. Amidst loud applause the delegate of the 14th Don Cossack Regiment stated that he “had much pleasure in extending the hand of friendship” to the representative of the 4th Cossack Regiment.[4]

The plot failed. The Cossack regiments refused to take part in the religious procession.

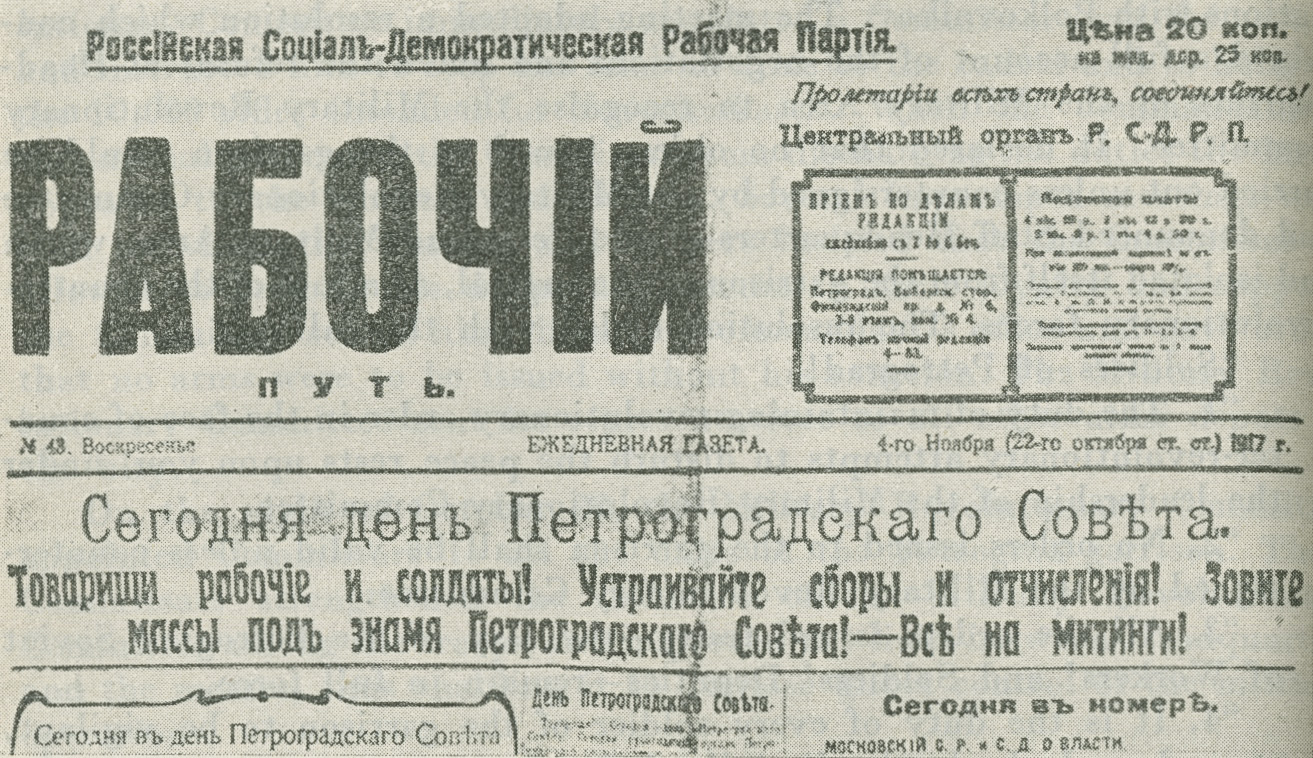

October 22 turned out to be a review of the forces of the Petrograd proletariat, in which the latter demonstrated its readiness to fight under the Bolshevik flag.

Numerous meetings were held in the units of the garrison and in the factories. The results exceeded the most sanguine expectations. Several thousand men attended the meeting in the People’s Palace. So crowded was the hall that soldiers and sailors found precarious seats up among the girders, while thousands thronged the grounds outside.

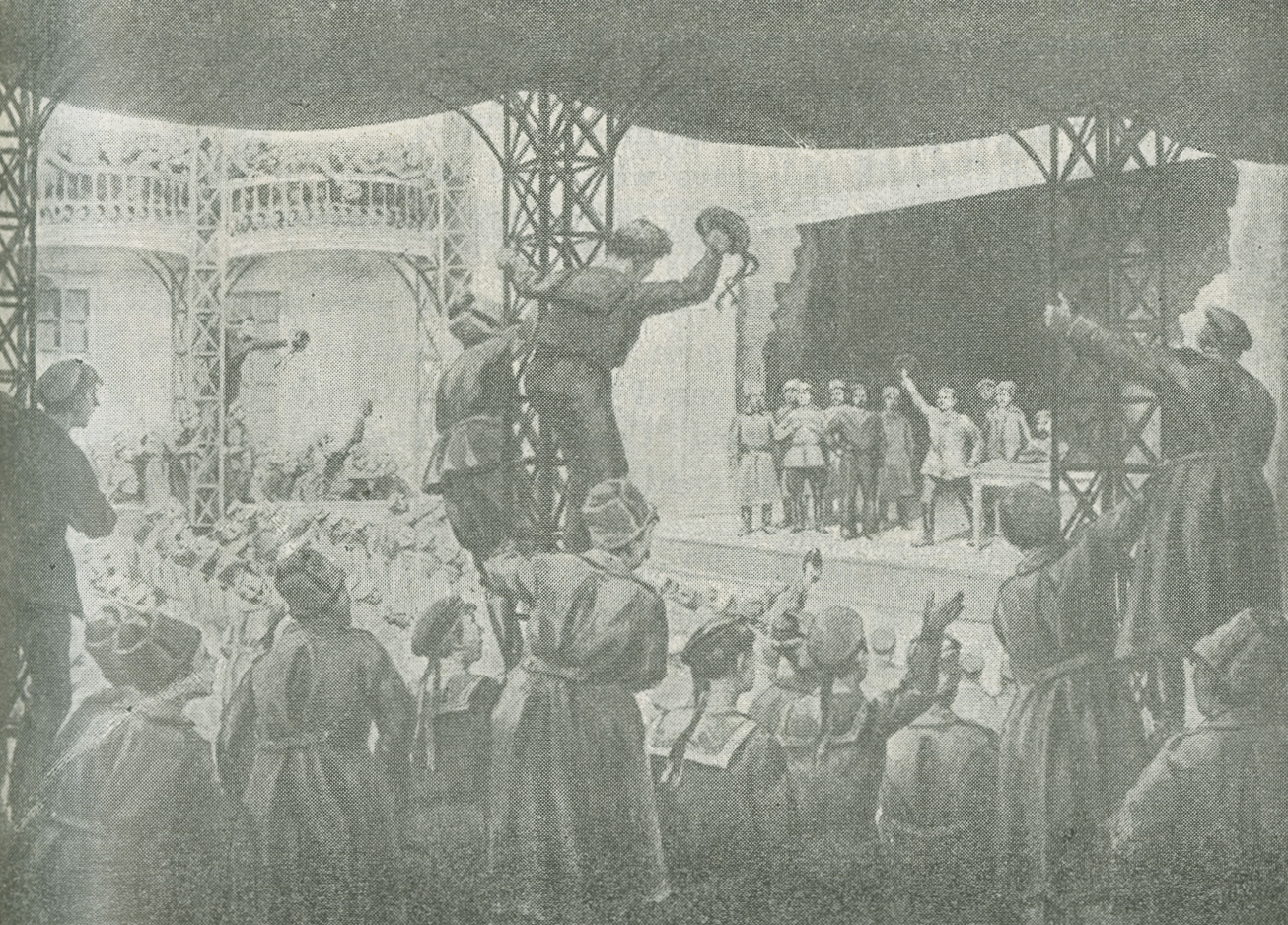

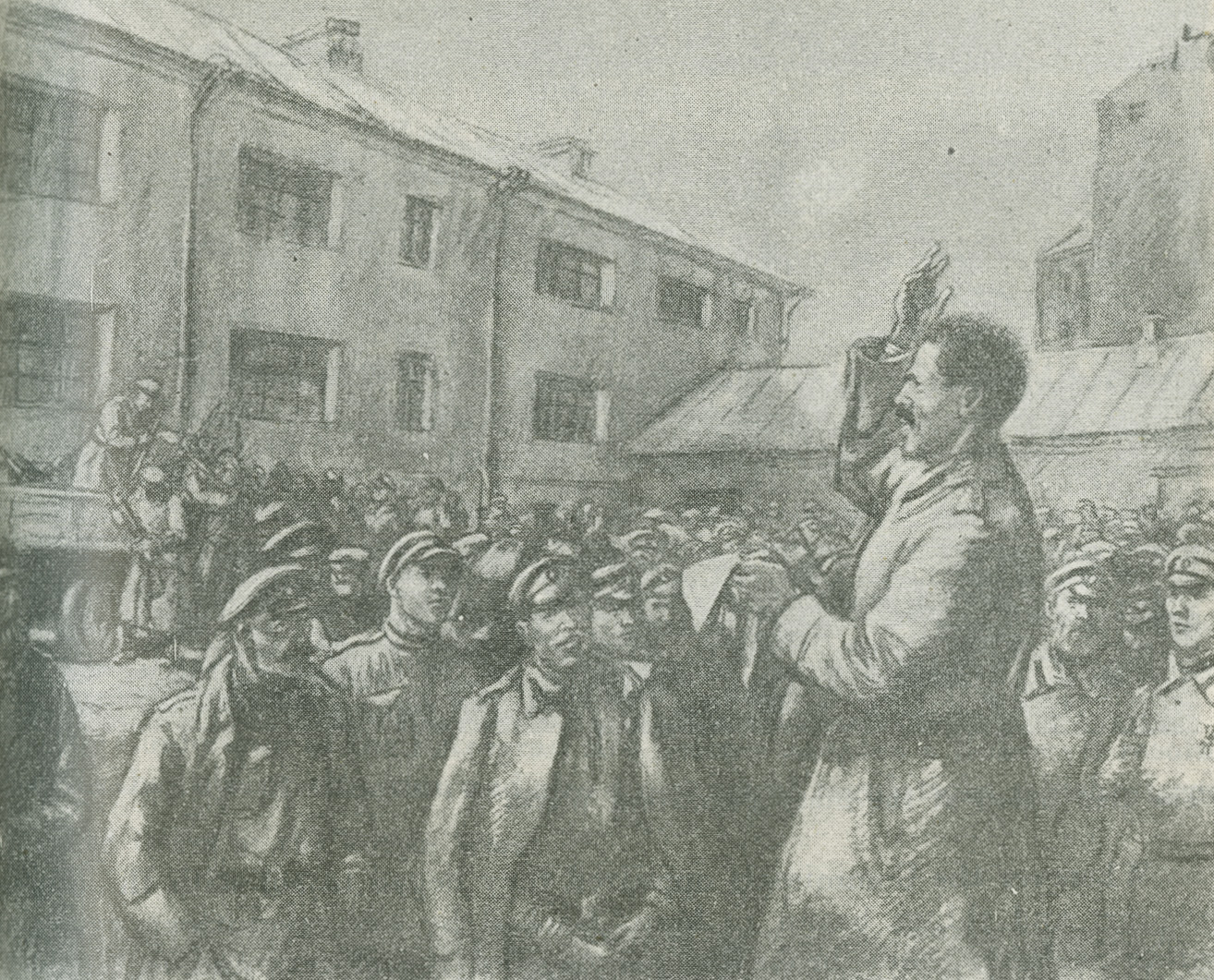

Greetings were conveyed to revolutionary Petrograd “from the banks of the Volga” by a representative of the Tsaritsyn Soviet. A Baltic Fleet delegate who declared that the sailors would die rather than allow the policy of compromise to continue was greeted with a storm of applause. So whole-hearted was the enthusiasm of the thousands of workers and soldiers assembled at this meeting that the least call would have been sufficient to cause this mass of humanity to rush bare-handed to the barricades and to face death. In response to the invitation of the Bolshevik speakers, all those present solemnly pledged themselves with arms upraised to rush into the fray against the government of the bourgeoisie at the word of command of the Petrograd Soviet. Similar scenes were witnessed all over Petrograd. Meetings were held in every factory and every barracks attended by vast numbers of soldiers, working men and working women.

That day the Party sent all its available propagandists to the districts. Requests for speakers came from all sides. When a speaker had finished addressing one meeting he was sent to another, and in this way each Bolshevik speaker addressed numerous meetings in the course of that day. At many of the meetings the tall, slender figure of V. Volodarsky, one of the best Bolshevik propagandists in Petrograd, was seen on the platform. A brilliant orator, Volodarsky was extremely popular among worker and soldier audiences. Wherever a severe tussle with the compromisers was expected, Volodarsky was invited to speak. The districts would telephone the Party Headquarters and say: “Send us Volodarsky; it’s going to be a big meeting.”[5]

Many of the Bolshevik delegates who were arriving in Petrograd for the Second Congress of Soviets also volunteered to address meetings of workers and soldiers.

The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries were being dislodged from their positions. At a meeting in the Polytechnical Institute, in the Vyborg District, the speech delivered by the Menshevik leader Martov began and ended with the one word “Comrades!” The audience refused to listen to him. His voice was drowned by cries of: “Get down! Shut up! Clear out, Kornilovite!”

At the Putilov Works October 22 was a day of remarkable enthusiasm. Workers who were present at that meeting relate that “we decided to take power in our own hands.” The Menshevik Sukhanov, in his Memoirs of the Revolution, complained that after several attempts to speak he was obliged to abandon the effort because the workers would listen to none save the Bolshevik speakers.[6]

On the night of October 22 the Military Revolutionary Committee sent telephone messages to the regiments of the garrison informing them of the decision to appoint Commissars for all the units, and instructing them to carry out only such orders emanating from Staff Headquarters as were countersigned by the Military Revolutionary Committee.

Late that night, A. I. Konovalov, the Deputy Prime Minister, accidentally learned of these telephone messages and hastened to the Winter Palace to inform Kerensky, who knew nothing about them. Konovalov expressed surprise that Staff Headquarters of the Military Area had not informed the government.

The appointment of the Regimental Commissars and the demand of the Military Revolutionary Committee that all the orders of Staff Headquarters of the Area should be sent to it for endorsement were regarded by the government as the beginning of the actual seizure of power by the Soviets.

For several days past the Provisional Government had been living in a state of growing alarm. The energy spent in concentrating forces appeared to have been fruitless. It seemed as though the revolution was forestalling the government’s measures. Kerensky formed battalions of shock troops, but the Bolsheviks formed a far larger number of battalions of the Red Guard. The counter-revolutionary generals sent Cossacks to the rear, but the Bolsheviks at the front won over division after division. The Provisional Government intended to utilise several thousand Polish Legionaries and Czechoslovaks, but the revolution won to its side vast masses of the working people of the oppressed nationalities.

The Provisional Government strained its efforts to the utmost to muster armed detachments, but it seemed to make no progress. The members of the government rushed hither and thither like animals in a cage. Kerensky spent all his time travelling. From the revolution that was maturing in the capital he fled to the front; but even there the sinister news reached him of the impending armed insurrection. The newspapers were full of rumours, insinuations and predictions, culled from “trustworthy sources.” Day after day this stream of rumour electrified the atmosphere, kept the country in a state of nervous tension and whipped up the temper of the masses. On October 15, Rech, the organ of the Constitutional Democrats, reported:

“At 1 o’clock this morning, the City Militia Administration received from various Commissariats information about the movements of armed Red Guards.”[7]

On October 18 it reported:

“The Bolsheviks are feverishly, perseveringly and persistently preparing for a massacre. They are collecting arms, planning operations, and occupying strong points.”[8]

On October 19 it reported:

“The industrial workers are hurriedly arming for the forthcoming action of the Bolsheviks. On October 17 and 18 arms—rifles and revolvers—were issued to the workers in the main Bolshevik stronghold—the Vyborg District. On October 18, arms were issued to the workers in the Bolshaya and Malaya Okhta, and at the Putilov Works.”[9]

On October 20 it reported:

“We have reached the 20th of October, the date which not only St. Petersburg, but the whole of Russia associates with fresh anxieties and forebodings. To give the Bolsheviks their due it must be said that they are doing everything to keep the state of alarm at the necessary level so as to intensify these forebodings and to bring the state of tension to the pitch when the guns begin to shoot of their own accord.”[10]

The first question the members of the Provisional Government asked themselves every morning was: “Will the Bolsheviks take action today?” The Ministers made guesses at the date on which the insurrection would break out. They pricked up their ears at every rumour that decisive action had already commenced. Konovalov, the Deputy Prime Minister, stated to a newspaper correspondent:

“On October 16 the Provisional Government had no exact information as to the day on which the Bolsheviks would take action. On the previous evening the Provisional Government had received information that the Bolsheviks had decided to take action not on the 20th, as everybody believed, but on the 19th. Evidently, the Bolsheviks themselves had not yet definitely decided that question,” he concluded in an effort to console himself.[11]

The situation was made more complicated for the Provisional Government by the fact that the Bolsheviks were preparing for an assault under the guise of defence. Camouflaging the offensive in the guise of defence was the specific feature of the Bolsheviks’ tactics during those days. The prevention of the withdrawal of the troops from the capital marked the beginning of the revolution, but that step had been taken on the plea of protecting Petrograd from the Germans and the counter-revolution. The Military Revolutionary Committee had been set up as the Battle Headquarters of the revolution, but this was done on the plea of strengthening the defence of the city. The appointment of Commissars over the regiments signified the mobilisation of the revolutionary forces, but this was done on the plea of defending the Petrograd Soviet from an onslaught by the reaction. As Stalin wrote:

“The revolution, as it were, masked its offensive operations in the cloak of defence in order the more easily to bring within its orbit the irresolute and vacillating elements.”[12]

By means of this skilful manoeuvre, the Bolsheviks deprived the Provisional Government of a pretext for accusing them of unleashing civil war, and also hindered the Provisional Government in mobilising the vacillating elements.

The state of constant tension in which the Bolsheviks kept the government caused confusion and friction in its ranks. On October 14 all three Deputy Ministers of Justice handed in their resignations and accused Malyantovich, the Minister of Justice, of conniving with the Bolsheviks because he had released several Bolsheviks on bail.

Kerensky summoned Malyantovich and told him in sharp terms that he had acted wrongly.

Soon after this, the question of Verkhovsky, the Minister for War, came up. The government had already had several minor conflicts with him. The first arose in connection with the formation of the Demobilisation Committee. Verkhovsky was of the opinion that this committee should be under his jurisdiction, but the government had placed it under the jurisdiction of another Minister, namely, Tretyakov. The second dispute arose over the question of demobilising men of the older age groups. The Minister for War had emphatically opposed this measure on the plea that this would weaken the forces at the front. Obviously scared by the growth of revolutionary temper in the army, the Minister ceased to attend the meetings of the Cabinet, vaguely hinting at his disagreement with it. In reply to the request to send a substitute, Verkhovsky practically handed in his resignation. To prevent this matter from becoming public the government granted him leave of absence.

The Provisional Government was in a continuous state of crisis.

Marked vacillation was also observed in the Pre-parliament. On October 18 that assembly discussed the question of national defence. The Constitutional Democrats, the Cossacks, the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Co-operators moved a joint resolution which was carried on a show of hands by 141 votes against 132. This happened at 2 o’clock in the afternoon. Ten minutes later the Mensheviks demanded a division. This time the resolution was defeated by 139 votes against 135. After that, five other motions were put to the vote: two moved by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and three by various groups of Mensheviks. They were all defeated.

When the adjournment was announced all the party groups were given an opportunity to confer in order to come to an understanding, but no agreement could be reached. In the end, on the question of defence—the most vital question affecting the country—the Pre-parliament did not adopt any resolution.

In this atmosphere of nervous tension and utter consternation the decision of the Military Revolutionary Committee to appoint Commissars caused utter dismay.

On October 22 Kerensky very excitedly telephoned General Bagratuni, Chief of Staff of the Petrograd Military Area, and in very sharp terms ordered him to refuse to recognise the Commissars under any circumstances. He ordered that “an ultimatum be presented calling for the rescindment of the telephone message by the body on whose instructions it had been issued,”[13] in other words, that the Military Revolutionary Committee should rescind its own order.

All night long the government sat in conference, now with Staff Headquarters of the Military Area and now with the Minister for War. Several Ministers were summoned to the Winter Palace. The members of the Council of the Russian Republic arrived. Lights appeared in the windows of the Mariinsky Palace, where the Councillors assembled. There they appraised the telephone message of the Military Revolutionary Committee as the beginning of the struggle for power. The Provisional Government fully concurred with Kerensky and Konovalov that it was necessary to take decisive measures against the Military Revolutionary Committee.

In the morning of October 23 the Military Revolutionary Committee publicly announced that it had appointed Commissars to all the units of the garrison. In its statement it said:

“As representatives of the Soviet, the Commissars enjoy complete immunity. Resistance to the Commissars is tantamount to resistance to the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.”[14]

Early in the morning of October 23, Kerensky resumed his conversations with the Ministers and with the officers of Staff Headquarters. As the Military Revolutionary Committee had shown no intention of rescinding its telephone message, it was decided to offer a compromise by giving the Petrograd Soviet increased representation at Staff Headquarters. This offer was communicated to the Smolny, but the Military Revolutionary Committee made no reply. Meanwhile, the Commissars appointed by the Committee appeared in the regiments of the garrison in ever increasing numbers.

Later in the day a secret session of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik Bureau of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet was held, not in the Smolny, where the Central Executive Committee usually held its meetings, but in the Mariinsky Palace. The meeting passed a resolution condemning the Military Revolutionary Committee and calling upon the government to take determined measures, even to the extent of arresting the heads of the Committee.

While Kerensky was rushing to and fro between the Winter Palace and the Mariinsky Palace, the Military Revolutionary Committee continued to send its Commissars to the regiments. During the first day it appointed about 100 Commissars, and within the next few days about 600 more.

Wherever the Commissars appeared they began to act with the utmost vigour, and things began to hum. Backed by the revolutionary section of the soldiers, they broke the sabotage of the officers and isolated the commanders, or else replaced them with N.C.O.’s and privates. In each regiment a nucleus of devoted revolutionary fighters was soon formed. General meetings of the soldiers were held at which the class meaning of the events then taking place was explained and resolutions were adopted pledging support to the Military Revolutionary Committee. The Commissars procured arms and supervised the distribution of food supplies. The fighting efficiency of the regiments in the garrison increased.

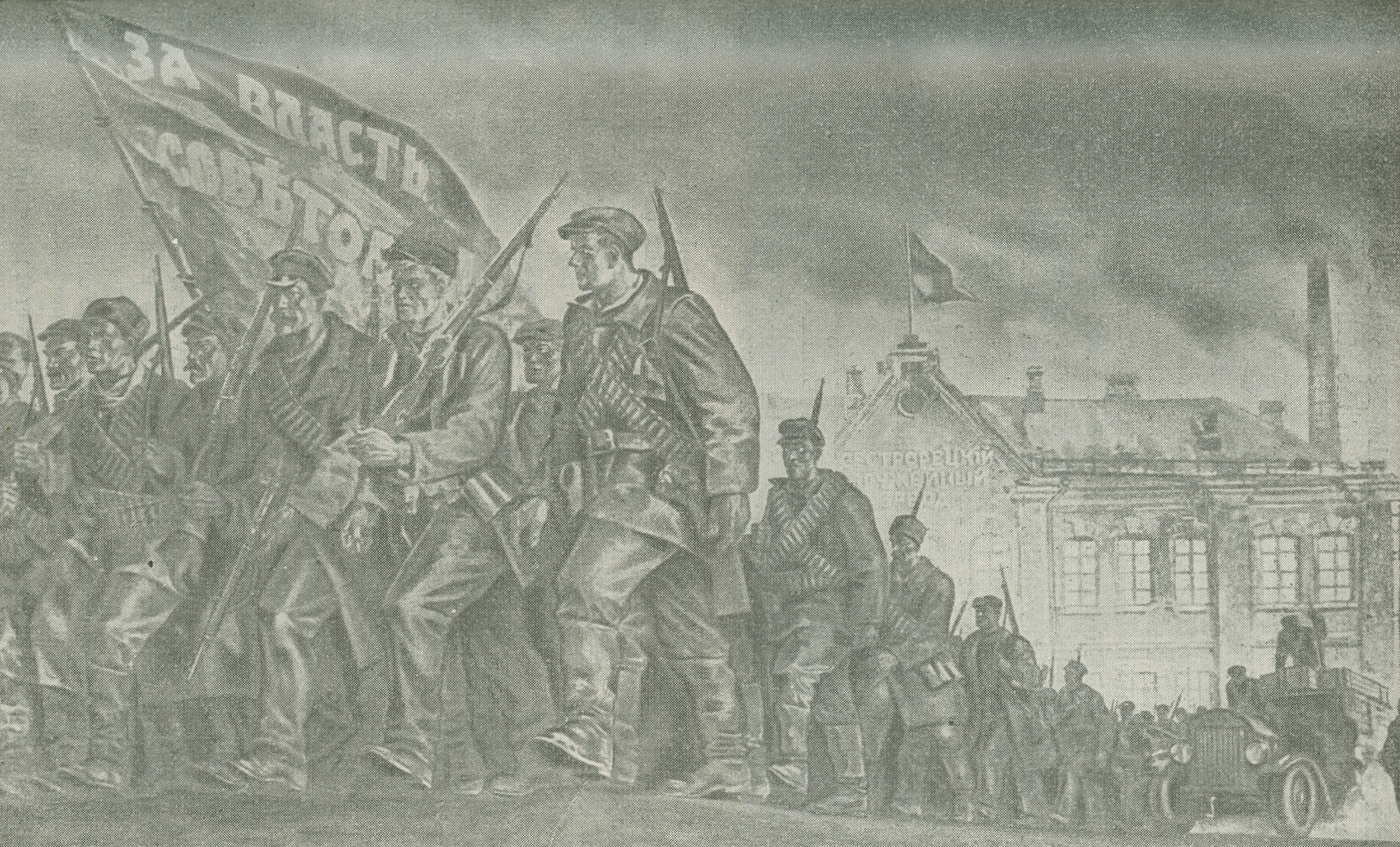

While the overwhelming majority of the garrison was being won over, the organisation of the main fighting forces of the October Revolution, namely, the workers’ Red Guard, was completed.

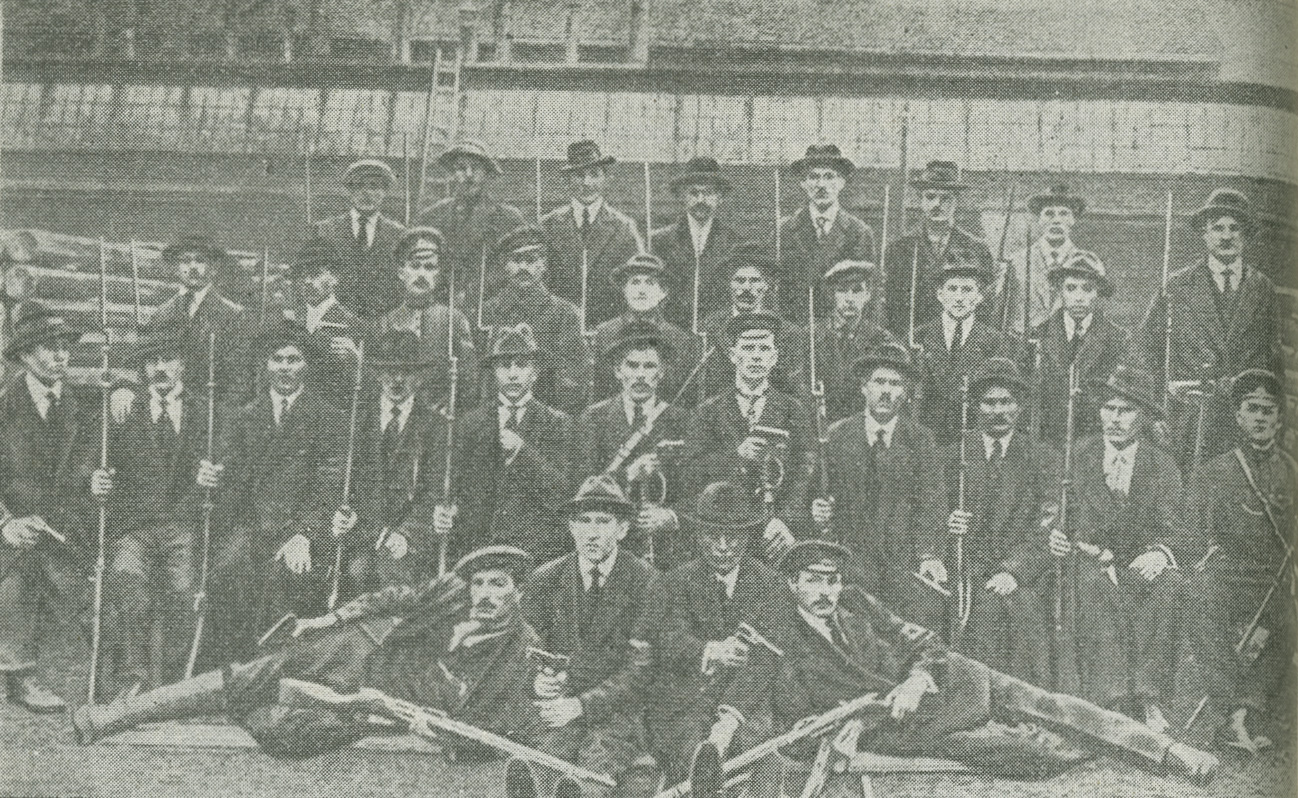

On October 20, after careful preparations had been made, a City Conference of the Red Guard of Petrograd and its suburbs—Sestroretsk, Schlüsselburg, Kolpino and Obukhovo—was opened in the premises of the Soviet of the First City District. One hundred delegates were present, mostly Bolsheviks, representing about 12,000 officially enrolled Red Guards.

The Red Guards grew in number literally hour by hour, for enrolment proceeded in every factory. No strangers could enrol in the Petrograd Red Guards; only those who worked at the given factory could join. This secured the Red Guard of the capital against the penetration of shady elements. The force was under the constant supervision of the workers in the factory. In a number of shops at the Putilov Works the Red Guards were elected at general meetings of the workers, and they proudly regarded themselves as the delegates of the plant.

There was not a factory where detachments were not formed. Even many rank-and-file Mensheviks, carried away by the general enthusiasm, begged to be enrolled in the Red Guard.

Working women too joined the detachments. At the Army Medical Supplies Factory a women’s first-aid detachment was formed. Their example was followed by other factories. Not a single Red Guard detachment left for the Smolny without a women’s first-aid unit. Working women performed guard duty with the men, and with them prepared for battle.

The reports made by the district representatives at the City Conference indicated that the Red Guards were full of determination and enthusiasm. Whenever a Soviet called for two men, five responded. If ten volunteers were called for, the whole detachment offered to go. The Red Guards no longer left their rifles at the factory; they took them home and always kept them ready to hand.

The Conference of the Petrograd Red Guards adopted a Bolshevik resolution on the current situation and also a new set of regulations which placed the organisation on a uniform basis, tightened up discipline and strictly defined the rights and duties of the General Staff, the Bureau, and the district staffs. According to the new regulations, each district was to have one permanent representative at General Headquarters. The Vyborg and the Porkhovo Districts were allowed two representatives.

The conference ended on October 23. The smell of powder was in the air. A conference of the General Staff of the Red Guard and representatives of the districts was hastily convened at which a Staff Bureau was elected. The General Staff gave orders to keep the Red Guard under arms, to have Red Guards permanently on duty at the factories, and to reinforce the patrols and scouting parties.

Next to the Red Guard, the most important fighting force of the revolution was the Baltic Fleet. The sailors had long been bitterly hostile to the government. As early as September 19, the Central Committee of the Baltic Fleet had adopted a resolution stating that it “would no longer carry out the orders of the Provisional Government or recognise its authority.”[15]

The majority of the naval officers kept away from the meetings of the sailors on the plea that they were “non-party” and “non-political.” The sailors, however, wholly and entirely supported the Bolsheviks.

In the evening of October 23, the Military Revolutionary Committee called together the Regimental Committees of the garrison. The meeting was also attended by many delegates from the front who had arrived for the Second Congress of Soviets. The meeting lasted over six hours, during which the representatives of the regiments reported on the temper prevailing among their men. These reports were listened to with the closest attention, and every now and again were interrupted by loud applause. The representatives of the Petrograd Guards Regiment and of the Moscow Reserve Guards Regiment declared that the time had arrived to transfer power to the Soviets. The delegate from the Ismailovsky Regiment expressed the sentiments of his regiment in the words: “All power to the Soviets!”

Amidst loud applause the representative of the 1st Rifle Division who had arrived from the Rumanian Front stated:

“The Provisional Government has done nothing to carry out the will of the working people and therefore all power in the country must be transferred to the Soviets.”[16]

He was followed by the representative of the Guards Rifle Division, which was at the front. He described the horrors of cold and hunger experienced by the men in the trenches.

Reports were also made by the representatives of the Grenadier Regiment, units of the Gatchina garrison, the 2nd Machine-Gun Regiment, and the Semyonovsky Regiment. One after another, the delegates declared that the soldiers of these units placed themselves entirely at the disposal of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.

Simultaneously, a meeting of the Petrograd Soviet was held at which a report was heard on the work of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

By an overwhelming majority the Petrograd Soviet passed a resolution approving of the Committee’s activities. The resolution stated:

“The Petrograd Soviet declares that thanks to the energetic activities of the Military Revolutionary Committee, firm contacts have been established between the Petrograd Soviet and the revolutionary garrison, and it expresses the conviction that only further activities in the same direction will enable the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which is about to open, to conduct its proceedings freely and without hindrance. The Petrograd Soviet instructs its Revolutionary Committee immediately to take measures to guard the safety of the citizens of Petrograd and, by determined measures, thwart attempts at rioting, looting, etc.”[17]

The Petrograd Soviet instructed its members to place themselves at the disposal of the Military Revolutionary Committee for the purpose of participating in its work.

When the meeting came to an end, late at night on October 23, the Party Centre called the Military Revolutionary Committee together, appraised the forces, and allocated the definite duties each unit was to perform when operations commenced. Every regiment left two representatives for liaison purposes.

The Military Revolutionary Committee had mustered against the counter-revolutionary offensive the politically conscious might of the Red Guard, the regiments of the garrison and the ships of the Baltic Fleet. The fighting forces of the revolution were only waiting for the word of command of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party.

Meanwhile, the Provisional Government was growing more and more alarmed. The Ministers communicated to each other rumours of an increasingly gloomy nature. Somebody in the Mariinsky Palace telephoned to the Winter Palace reporting the sentiments of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik groups in the Pre-parliament. Delegates who had attended the conferences of the garrison and the meeting of the Petrograd Soviet returned from the Smolny and reported that the garrison was preparing for action, and that the insurrection could be expected within the next few hours.

Kerensky summoned General Manikovsky, recently appointed Acting- Minister for War, and General Cheremisov, the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Front, to discuss measures “to avert a fresh attempt on the part of the Petrograd Soviet to violate discipline and disrupt the normal life of the garrison.”[18]

Both generals agreed that the Soviet’s influence on the garrison was “extremely pernicious.”

At 5 p.m. on October 23, Kerensky called a secret meeting of the officers of Staff Headquarters of the Petrograd Military Area at which General Bagratuni, the Chief of Staff, delivered a comprehensive report on the measures taken to counteract the operations of the Bolsheviks.

Information had got abroad of Trotsky’s proposal that the insurrection should be postponed until the assembly of the Congress of Soviets, i.e., until October 25, and it was assumed that, since Trotsky had mentioned that date, the Bolsheviks must have planned something for it. Acting on this treacherous warning the military men decided to get busy a day or two before the Bolsheviks. At the meeting of military men called by Kerensky it was proposed and agreed that action be taken on October 24.

At night, on October 23, the Provisional Government assembled to discuss a single item of business, viz., measures to combat the insurrection planned by the Bolsheviks. Kerensky in an excited tone quoted a number of facts proving that an insurrection was afoot, and in very emphatic terms demanded that action should immediately be taken against the Bolsheviks. Delay, he said, would undoubtedly be taken by the Bolsheviks as a sign of the government’s weakness. He then unfolded before the Ministers the plan of operations against the insurrection and in conclusion stated that he had already issued preliminary orders, namely the arrest of the heads of the Military Revolutionary Committee, primarily those who incited insubordination to the lawful authorities.

The government approved of Kerensky’s measures. Some of the Ministers recommended that efforts should be made to secure the support of the Pre-parliament, whose sanction would strengthen the government’s hand in carrying out its measures to suppress the Bolsheviks.

This proposal was adopted and the government instructed Kerensky to address the Pre-parliament. Late that night, as soon as the Ministers dispersed, Kerensky informed Staff Headquarters of the Petrograd Military Area that the plan of operations against the Bolsheviks had been approved.

The decisive moment had arrived. The opposing forces were lined up, facing each other and ready for action.

[1] “The Conference of the Petrograd Garrison,” Dyen, No. 194, October 20, 1917.

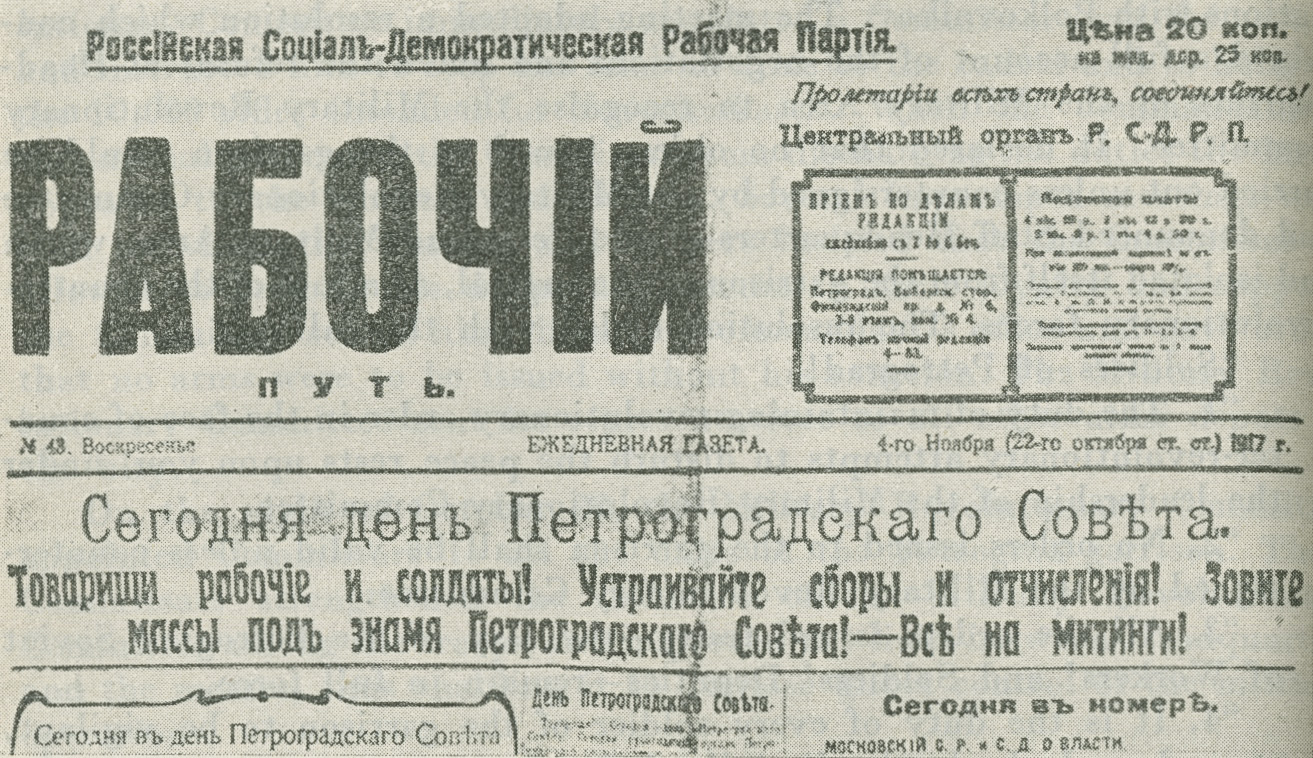

[2] “The Resolution of the Military Garrison Committee of the City of Petrograd,” Rabochy Put, No. 43, October 22, 1917.

[3] “To the Garrison in the City of Petrograd and of its Environs,” Rabochy Put, No. 44, October 24, 1917.

[4] “The Conference of the Petrograd Garrison,” Dyen, No. 196, October 22, 1917.

[5] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

[6] N. Sukhanov, Notes on the Revolution, Vol. VII, Berlin-St. Petersburg-Moscow, 1923, pp. 44 and 88.

[7] “The Latest News,” Rech, No. 243, October 15, 1917.

[8] “On the Eve,” Rech, No. 246, October 19, 1917.

[9] “The Bolshevik Action,” Rech, No. 246, October 19, 1917.

[10] Leading Article in Rech, No. 247, October 20, 1917.

[11] “The Provisional Government,” Dyen, No. 191, October 17, 1917.

[12] J. Stalin, On the October Revolution. Articles and Speeches, Party Publishers, Moscow, 1932, p. 64.

[13] L. Lvov, “In the Winter Palace,” Dyen, No. 197, October 24, 1917.

[14] “To the Inhabitants of Petrograd,” Rabochy Put, No. 44, October 24, 1917.

[15] “The Centroflot,” The Resolution of the Central Committee of the Fleet, Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, No. 177, Sept. 21, 1917.

[16] “The Meeting of Regimental Committees,” Dyen, No. 197, October 24, 1917.

[17] “The Meeting of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Rabochy Put, No. 45, October 25, 1917.

[18] “The Petrograd Soviet and the Government,” Novaya Zhizn, (New Life), No. 161, October 24, 1917.

Previous: Treachery

Next: The Beginning of the Insurrection