The entire mass of material wealth produced in society over a definite period, e.g., a year, constitutes the aggregate social product (or gross product).

Part of the aggregate social product, equivalent to the value of the constant capital which has been used up; in the course of the process of reproduction goes to replace the expended means of production. The cotton which has been worked up in the mill is replaced by an equivalent amount of cotton from the current year's harvest. Fresh masses of coal and oil take the place of the fuel which has been burnt up. Machines which have become obsolete are replaced by new ones. The remaining part of the aggregate social product embodies new value created by the working class in the process of production.

That part of the aggregate social product in which newly-created value is incorporated is the national income. The national income in capitalist society is consequently equivalent to the value of the entire aggregate social product less the value of the means of production expended during the year, or, in other words, it is equal to the sum of the variable capital and the surplus-value. As it exists in kind, the national income comprises the whole mass of consumer goods which have been produced together with that part of the means of production produced which goes to extend production. Thus the national income means, on the one hand, the total value newly created during the year, and on the other, a mass of material wealth of various kinds, part of the aggregate social product in which this newly created value is embodied.

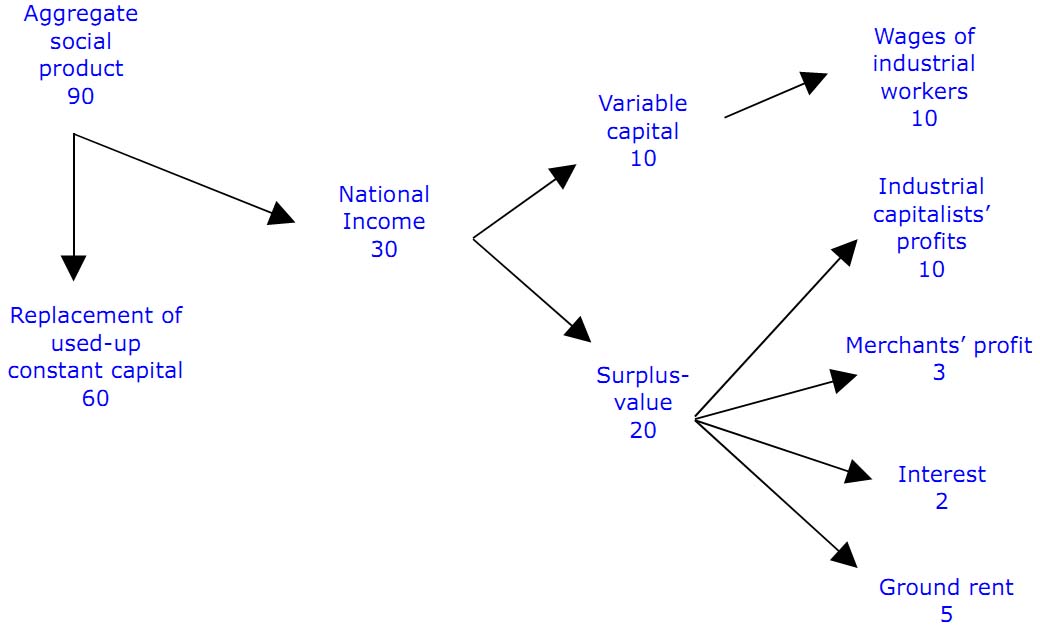

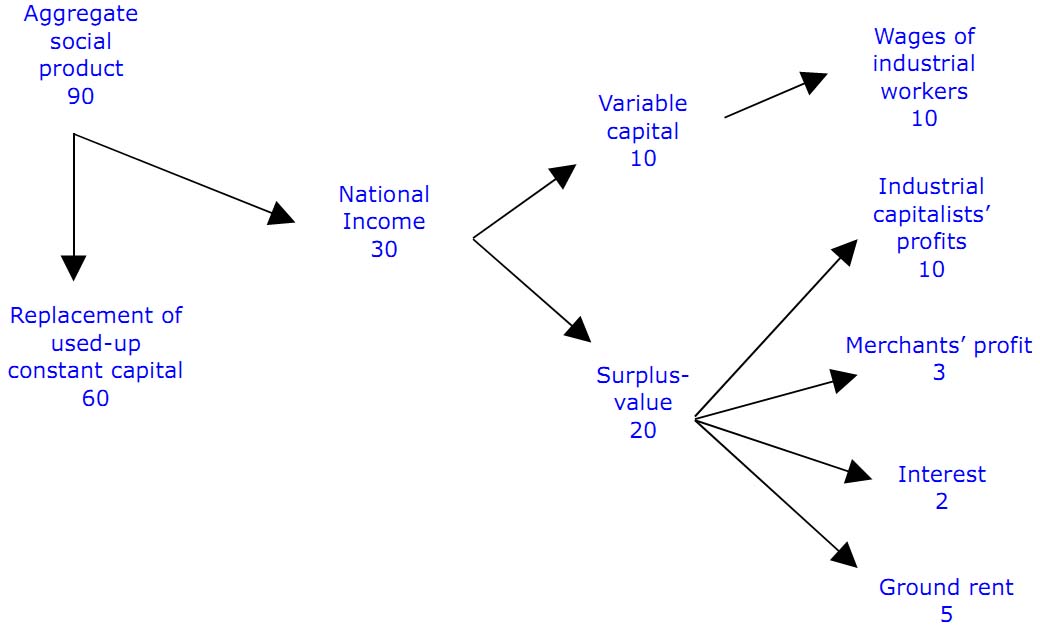

If, for example, in the course of a year commodities are manufactured in a particular country to the value of go milliard dollars or marks, and of this value 60 milliards go to replace the means of production used up during the year, then the national income created during the year will be 30 milliards.

Under capitalism there are a mass of small producers (peasants and artisans), whose labour also creates a definite part of the aggregate social product. For this reason a country's national income includes also the value newly created in the given period by the peasants and artisans.

The aggregate social product, and therefore also the national income, are created by workers employed in the various branches of material production. This means all those branches in which material wealth is produced: industry, agriculture, building, transport, etc.

The, national income is not created in the non-productive branches, to which belong the machinery of State, credit, trade (except for those operations in this branch which are a continuation of the process of production into the sphere circulation), medical institutions, places of entertainment, etc.

In capitalist countries a quite considerable part of the able-bodied population not only does not take part in producing the social product and national income, but is not in any way engaged in socially-useful labour.

To this category of persons belong first and foremost the exploiting classes and their numerous parasitic hangers-on, together with the huge police, bureaucratic and militaristic apparatus which upholds the system of capitalist wage-slavery. A great deal of labour-power is expended without any benefit to society. Thus, enormous unproductive expenditures of labour are connected with competition and with the unrestrained speculation and incredibly extravagant advertising which go on.

The anarchy of capitalist production, the devastating economic crises, and the working of enterprises substantially below capacity sharply restrict the utilisation of labour-power. Very great masses of the working people are deprived under capitalism of the opportunity to work. The number of fully unemployed registered in the towns of the bourgeois countries in the period 1930 to 1938 was never less than 14 million.

As capitalism develops, the State apparatus becomes more and more inflated; the number of persons in attendance upon the bourgeoisie grows, and while the portion of the population engaged in the sphere of material production is reduced, the proportion of persons engaged in circulation increases. The army of unemployed grows in size and agrarian surplus-population becomes more intense. The effect of all this is to limit very much the growth of the aggregate social product and the national income in bourgeois society.

In the U.S.A. the proportion of the able-bodied population engaged in branches of material production was in 1910 43.9 per cent, in 1920 41.5 per cent, in 1930 35.5 per cent and in 1940 about 34 per cent.

In the U.S.A. the average annual growth of the national income during the last thirty years of the nineteenth century amounted to 4.7 per cent, in 1900-1919 to 2.8 per cent, in 1920-38 to 1 per cent and in the years since the Second World War, 1945-54, to 0.7 per cent.

Each mode of production has its own historically determined forms of distribution. The distribution of the national income under capitalism is determined by the fact that ownership of the means of production is concentrated in the hands of the capitalists and landlords, who exploit the proletariat and peasantry. The consequence of this is that the national income is distributed not in the interests of the working people but in those of the exploiting classes.

Under capitalism the national income created by the workers' labour falls to the disposal, first of all, of the industrial capitalists (including capitalist entrepreneurs in agriculture). The industrial capitalists, when they realise the commodities produced, receive the full amount of their value, including the sum of variable capital and surplus-value. Variable capital is transformed into the wages which the industrial capitalists pay to the workers engaged in production. The surplus-value remains in the hands of the industrial capitalists; from it come the incomes of all the groups which constitute the exploiting classes. Part of the surplus-value is transformed into industrial capitalists' profit. A certain portion of the surplus-value is handed over by the industrial capitalists to the merchant capitalists in the form of merchants' profit and to the bankers as interest. Part of the surplus-value is handed over by the industrial capitalists to the landowners as ground-rent.

This distribution of the national income between the different classes of capitalist society can be depicted in the form of a diagram like this (the figures stand for milliards of dollars or marks, etc.):

Involved in this distribution is also that portion of the national income which is created in the given period by the labour of the peasants and artisans: part of this is taken by the peasants and artisans themselves, another part goes to the capitalists, (kulaks, purchasing agents, merchants, bankers, etc.) and a third part goes to the landlords.

The incomes of the working people are based on their personal labour and are earned incomes. The source of the incomes received by Aggregate social product the exploiting classes is the labour of the workers, together with that of the peasants and artisans. The incomes of the capitalists and landlords are based upon the labour of and are unearned incomes.

The unearned incomes of the exploiting classes are increased still more in the process of the further distribution of the national income. Part of the income received by the population, and in the first place of the working people, is redistributed through the State budget and used in the interests of the exploiting classes. Thus, part of the income of the workers and peasants, which finds its way through tax-payments into the State budget, is then transformed into additional income for the capitalists and into the income of officials. The burden taxation imposed by the exploiting classes on the working people grows rapidly.

In Britain at the end of the nineteenth century taxes amounted to 6-7 to 23 per cent, in 1950 to 38 percent; in France at the end of the nineteenth century taxes were 10 per cent of the national income, in 1913 13 per cent, in 1924 21 per cent and in 1950 29 per cent.

Furthermore, part of the national income is transferred, by way of payments for, what are called services, to the non-productive branches (e.g., for use of municipal services, medical aid, places of entertainment, etc.). As already pointed out, no social product is created in these branches, nor, consequently, any national income; but the capitalists who exploit the workers employed in these branches receive part of the national income created in the branches of material production. From this income the capitalists who own businesses in the non-productive branches pay the wages of their workers, meet the material outlay which they have to find (for premises, equipment, heating, etc.) and take their profit.

Thus, the payment made for services must replace the costs incurred by these concerns and ensure the average rate of profit, since otherwise the capitalists will not employ their capital in these branches. In their hunt for high profits the capitalists endeavour to inflate payments for services, which leads to a further fall in the real wages of the workers and the real incomes of the peasants.

The re-distribution of the national income which takes place through the budget and also through high payments for services intensifies the impoverishment of the working people.

As the outcome of this entire process of distribution, the national income is divided into two parts: (1) the income of the exploiting classes, and (2) the income of the working people, both those engaged in the material-production branches and those in the non-productive branches.

The share of the national income taken by the workers and other working people of town and country who do not exploit the labour of others amounted in the U.S.A. in 1923 to 54 per cent, while the share taken by the capitalists was 46 per cent; in Britain in 1924 the share of the wage-earners was 45 per cent; in Germany in 1929 the working people's share was 55 per cent and that of the capitalists 45 per cent. At the present time in the capitalist countries the working people, who make up nine-tenths of the population, receive considerably less than half of the national income, while the exploiting receive considerably more than half.

The working people's share of the national income steadily falls, while that taken by the exploiting classes grows. In the U.S.A., for example, the working people's share of the national income amounted in 1870 to 58 per cent, in 1890 to 56 per cent, in 1923 to 54 per cent, in 1951 to approximately 40 per cent.

The national income is used, in the last analysis, for consumption and accumulation. The way the national income is used in bourgeois countries is determined by the class nature of capitalism and expresses the ever-growing parasitism of the exploiting classes.

The share of the national income which goes toward the personal consumption of the working people, who are the principal productive force of society, is so low that, as a rule, it does not guarantee them even the minimum needed for subsistence. A very great number of workers and working peasants are obliged to deny themselves and their families necessities, to live wretchedly in hovels and to deprive their children of education.

A very substantial part of the national income goes toward parasitic consumption by the capitalists and landowners. Colossal sums are spent by the capitalists and landowners on buying luxury articles and on maintaining a numerous crowd of hangers-on.

Under capitalism the share of the national income which goes toward the extension of production is quite small in comparison with the possibilities and needs of society. Thus, in the U.S.A. the share of the national income going to accumulation amounted in the period 1919-28 to approximately 10 per cent; but in the decade 1929 to 1938 accumulation amounted on the average only to 2 per cent of the national income, while during the years of crisis a certain eating away of fixed capital took place.

The comparatively small size of accumulation under capitalism is due to the fact that a considerable part of the national income goes to the parasitic consumption of the capitalists, to unproductive expenditure.

Thus, the net costs of circulation which are incurred in the upkeep of the commercial and credit apparatus, the storing of surplus stocks, advertising, stock exchange speculation, etc., come to huge amounts. In the U.S.A., during the period between the first and second world wars, the net costs of circulation absorbed 17- 19 per cent of the national income.

A continually growing part of the national income under capitalism goes on war expenditure, the armaments race and the upkeep of the State apparatus.

On the surface of things in capitalist society, incomes and their sources appear in distorted, fetishistic form. A misleading appearance comes about, as though capital itself gave birth to profit and land to rent, while the workers created only the value of their own wages.

These fetishistic notions underlie the bourgeois theories about the national income. By means of theories of this kind bourgeois economists endeavour to muddle the question of the national income in a way which benefits the bourgeoisie. They try to show that not only the workers and peasants but also the capitalists and landowners, and such persons as officials, policemen, stockbrokers, clergymen, etc. all have a share in creating the national income.

Furthermore, bourgeois economists show in a false light the distribution of the national income. They understate the share of this income which is taken by the capitalists and landowners. Thus, for example, the incomes of the exploiting classes are given on the basis of the returns made by the taxpayers themselves, which markedly understate these incomes; they do not take into account the enormous salaries drawn by many of the capitalists as directors of joint-stock companies; they do not take into account the incomes of the rural bourgeoisie, etc. At the same time the incomes of the working people are artificially exaggerated through including in their ranks the high-salaried upper officials, managers of businesses, banks, commercial concerns, etc.

Finally, the bourgeois economists distort the real picture of the distribution of national income by omitting to separate off the expenditure on consumption by the exploiting classes and the net costs of circulation, by understating the share which goes to military expenditure and in every possible way concealing the unproductive spending of a large part of the national income.

The bourgeois State is an organ of the exploiting classes which has for its purpose to hold the exploited majority of society in subjection and to assure the interests of the exploiting minority in all spheres of internal and external policy.

The bourgeois State possesses a ramified apparatus for the fulfilment of its tasks: army, police, punitive and judicial bodies, intelligence service, and various instruments for administrative control and ideological influence over the masses. This machinery is kept up out of the State Budget. Taxes and loans provide the sources of the money for the State Budget.

The State Budget is an instrument for the redistribution of part of the national income in the interests of the exploiting classes. It takes the form of an annual estimate of State income and expenditure. Marx wrote that the Budget of the capitalist State is nothing but "a class Budget-a middle class Budget" (Marx, "L.S.D. or Class Budgets, and Who's Relieved by Them", in The People's Paper, No. 51, April 23, 1853).

The expenditure of the capitalist State is to an overwhelming degree unproductive.

A very great portion of the resources of the State Budget under capitalism goes on war and war preparation. With this should be grouped also expenditure on scientific research in the field of the production and perfection of new weapons of mass annihilation, and on subversive activity in other countries. Another large portion of the expenditure of capitalist States is connected with the maintenance of an apparatus for holding down the working people.

"Contemporary militarism is the result of capitalism; it is the 'living manifestation' of capitalism in both its forms: as a military force used by the capitalist States in their external conflicts... and as a weapon in the hands of the ruling class for the suppression of all movements (economic and political) of the proletariat." (Lenin, "Militant Militarism and the Anti-militarist Tactics of the Social Democrats", Selected Works, 12-vol. edition, vol. IV, p. 325.), Very considerable sums are spent by the State, especially during wars and crises, on direct subsidising of capitalist businesses and guaranteeing them high profits. Frequently the subsidies paid out to banks and manufacturers have the purpose of saving them from bankruptcy during crises. By means of State purchases paid for out of the Budget, milliards of additional profit are pumped into the pockets of the big capitalists. Expenditure on culture and science, education and public health takes an insignificant share of the State Budgets of the capitalist countries. In the U.S.A., for example, more than two-thirds-of the total Federal Budget has in recent years been spent on war purposes, while public health, education and housing took less than 4 per cent, of which less than 1 per cent went on education.

The capitalist State obtains the bulk of its revenue by way of taxes.

In Britain, for example, taxes made up 89 per cent of the total amount of the Budget in 1938.

Taxes serve, in capitalist conditions, as a form of additional exploitation of the working people by way of redistribution through the Budget of part of their incomes for the benefit of the bourgeoisie. Taxes are called direct if they are assessed on the incomes of particular persons, and indirect if they are charged on goods sold (chiefly mass consumption goods) or on services (e.g., cinema and theatre tickets, tickets for travel on municipal transport, etc.). Indirect taxes raise the prices of goods and the charges for services. Indirect taxes are in fact paid by the consumers. The capitalists also transfer to the consumers part of their direct taxes, if they succeed in raising the price of goods or services.

The policy of the bourgeois State is directed towards reducing as much as possible the rate of taxation falling on the exploiting classes. The capitalists evade paying their taxes by concealing the true amount of their incomes. The policy of indirect taxation is particularly advantageous for the propertied classes.

"Indirect taxation charged upon articles consumed by the masses is distinguished by its very great injustice. It casts all its weight upon the poor, creating a privileged situation for the rich. The poorer a person is, the larger the share of his income that he pays to the State in the form of indirect taxes. The masses who own little or no property make up nine-tenths of the whole population, consume nine-tenths of all the taxed articles and pay nine-:tenths of the total amount of indirect taxes." Lenin, "Apropos of the Public Estimates", Works, Russian edition, vol. v, p. 309.)

Consequently the main burden of taxation falls on the working masses: the manual and clerical workers and the peasants. As mentioned above, at the present time in the bourgeois countries about a third of the wages of the manual and clerical workers is drawn into the State Budget through taxation. High taxes are exacted. from the peasants and intensify their impoverishment.

Besides taxes, an important item on the revenue side of the Budget in capitalist States is loans. Most often the bourgeois State resorts to loans to cover exceptional expenditure, in the first place war expenditure.

A considerable part of the resources which are gathered by way of loans are spent on State purchases of arms and supplies for the armed forces, which bring large profit to the manufacturers. In the long run loans lead to further increases in taxation of the working people, to pay interest on the loans and to pay off the loans themselves. The size of the State debt grows rapidly in bourgeois countries.

The total amount of State indebtedness throughout, the world grew from 38 milliard francs in 1825 to 250 milliard in 1900, i.e., it was multiplied by 6.6. In the twentieth century it grew still faster. In the U.S.A. in 1914 the State debt amounted to 1.2 milliard dollars, and in 1938 to 37.2 milliard, i.e., to thirty-one times as much. In Britain in 1890 £24,100,000 was paid out in interest on loans, and in 1953-4 £570,400,000. In the U.S.A. in 1940 a milliard dollars were paid in loan interest, and in 1953-46.5 milliard.

One of the sources of revenue for the State Budget under capitalism is the issue of paper money. Bringing inflation and, rising prices in its train, the issue of paper money transfers part of the national income to the bourgeois State at the cost of a lowered standard of living for the masses.

Thus the State Budget under capitalism serves as an instrument in the hands of the bourgeois State for additional robbery of the working people and enrichment of the capitalist class, and enhances the tendency to unproductiveness and parasitism in the way the national income is used.

(1) The national income in capitalist society is that part of the aggregate social product in which newly created value is embodied. The national income is created in the branches of the economy where material production takes place, by the labour of the working class together with that of the peasants and artisans. As it exists in kind, the national income consists of the whole mass of consumer goods produced and that part of the means of production which is set aside for extending production. Under capitalism a considerable section of the able-bodied population not only does not create national income but does not even take part in socially-useful work.

(2) The distribution of the national income under capitalism is effected in the interests of the enrichment of the exploiting classes. The share taken by the working people in the national income falls while that taken by the exploiting classes increases.

(3) Under capitalism the national income, created by the working class, is distributed in the form of wages to the workers, profits to the capitalists (manufacturers, merchants and owners of loan-capital) and ground-rent to the landowners. A considerable part of what results from the labours of the peasants and artisans is also appropriated by the capitalists and landowners. Through the State Budget and by way of high charges for services a redistribution of the national income is carried out which still further impoverishes the working people.

(4) A huge and ever-increasing part of the national income under capitalism is used unproductively: it is spent on parasitic consumption by the bourgeoisie, on covering the excessively inflated costs of circulation, on the upkeep of the State apparatus for holding down the masses and on the preparation and conduct of predatory wars.