The analysis of the "immediate process of capitalist production" (SG 26) traces the commodities C1 (that are realised at a definite price M1 in the circulation of capital M - C ... P ... C1 - M1 ), to their sphere of production. The quantitative difference between M - the money-form of the value of all elements of production - and M1 - the money-form of the value of the product - must stem from a difference in the duration of the labour-process (SG 27) that produced C and C1. This is a mere consequence of the assumption of presentation justified above: that social surplus-value, because it can't spring from circulation, has to be explained "even though the price and value of a commodity be the same", that is, on the basis of the determination of value by abstract, general labour. It is now systematically indispensable to introduce the category 'magnitude of value' (SG 28) determined by the intensity and duration of that labour, which forms the substance of value. Our task can now be formulated as follows: In order to solve the riddle of how capitalists make more money out of their money we have to understand the difference in the magnitudes of value of C and C1.

C comprises everything necessary to produce C1. All the "elements of production" have commodity-form. The means of production are industrial commodities that have been produced before, and labour-power is a second order commodity the price of which is the money-expression of the value of those industrial commodities ("means of life") that are individually consumed (SG 29) by the labourer (and dependants). Capitalist production is private labour (SG 30) insofar as labour-power, raw materials and means of labour are all private property (SG 31) of the capitalists. That is why the products of this labour-process are also the capitalists' private property (SG 32).

To understand how valorisation of value M - C . . P . . C1 - M1 is possible, we firstly have to mark out the point of departure of the capitalist process of production more explicitly as:

| M - C | < | MP LP |

(where 'MP' stands for: means of production, and 'LP' stands for: labour-power). And secondly we have to deal with what happens with the value of MP and what happens with LP in the course of the production process.

If the production of MP - by assumption of presentation industrial commodities - is a necessary step in the production of C1 then the labour socially necessary (SG 33) to produce MP forms a part of the labour that is congealed in the value of C1. The value of the industrially produced means of production ("old value") is "transferred" to the value of the product (SG 34).

The other part of the value of the commodities C1 is called "new value" (SG 35) because it has been newly produced in "the final operation" of the total production process that is under our present consideration. The old value is a magnitude of value that C and C1 have in common. Therefore the difference in the magnitude of value of C and C1 has to be explained with respect to a comparison of the new value of C1 and the remainder of C when the value of MP, that reappears in the form of the old value of C1, is subtracted.

As C is composed of MP and LP, and MP has already been dealt with, this comparison amounts to a comparison of the duration and intensity of labour-process1, in which (along with MP) labour-power is consumed productively and the duration and intensity of labour-process2 in which the industrial commodities that are consumed by the labourer individually are produced. And this is Marx's solution of the riddle of surplus-value (SG 37). The surplus stems from longer duration and intensity of labour process1 in comparison with labour-process2. The difference in duration between the two processes is then terminologically expressed, in calling that part of labour-process1 that is equally long as labour-process2 taking into account any difference in intensity of labour: "necessary labour-time" (SG 38), because it is the labour-time socially necessary to produce the labourers' means of life (SG 36). The remaining part of labour-process1 is called" "surplus-labour-time" (SG 39).

The value of the industrial commodities C1 that are the result of a capitalist process of production can now be conceived as C1 = c + v + s where 'c' stands for the old value that remains constant, C ("constant capital" (SG 10)), and 'v + s' stands for the new value with respect to which the part of capital that was expended to buy labour-power appears as "a variable magnitude" because, looking at the process of production that made C1 out of

| C | < | MP LP |

, v as a part of M is "transformed" into v + s, that part of M1 which did not remain constant (SG 41) ('v' stands for 'variable capital" and 's' stands for "surplus-value", cf. CI 204ff).

The "rate of surplus-value" (SG 43) denotes the division of the working-day (SG 42) into necessary labour-time and surplus labour-time. Keeping in mind how the analysis led to the expression 'variable capital' we can call s/v rate of valorisation (SG 44) of variable capital.

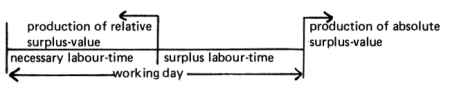

The extraction of surplus-value is the basis of the class contradiction between capital and wage-labour i.e. the daily practice of capitalist production is a class struggle (SG 45) which, while capitalist production continues, the capitalist class wins. The rate of surplus-value is a measure of the degree of exploitation of the labourers (SG 46) because it expresses the ratio of unpaid to 'paid' labour (SG 47) and the attempt by capital to increase this rate sharpens the class contradiction. Capital is money advanced to make more money i.e. it is value going through the circulation M - C - M1 in which the maximum increase of M is sought (SG 28). Hence in the systematic language we can say that capital seeks to maximise surplus-value production and can draw the following scheme to illustrate the possibilities of an increase in the valorisation of variable capital (SG 49):

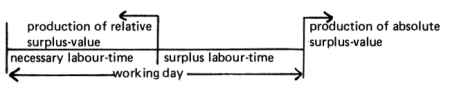

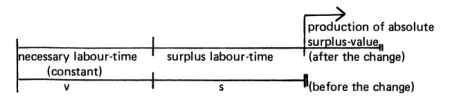

Production of "absolute surplus-value" (SG 50) is possible by mere prolongation of the working-day, even though the productivity of labour (SG 51) remains constant. Socially, the production of "relative surplus-value" (SG 52) is possible only by an increase in the productivity of labour which leads to a reduction in the value of the industrial commodities that serve as the labourers' means of life. The analysis at this point proceeds under the assumption of presentation that the class struggle is limited to the maintenance of uniform, real wages (SG 53) (which is expressed by Marx as: commodities, including labour power, are exchanged at their values). This assumption will be relaxed in Paper 5.

Given a constant wage per day, the capitalist may find a way to make n labourers work a longer working-day equivalent to that worked by n + m labourers in a shorter working-day. In this case, he achieves the same result C1that he sells for M1 for less money than M. (He saves the variable capital for m labourers.) If he goes on using the same amount of money as capital, he can use more than n labourers in this more profitable way with the production of C1 increased:

As the necessary labour-time is constant, the prolongation of the labour time means an increased production of surplus-value. (cf. CI 299: "The surplus-value produced by prolongation of the working-day, I call absolute surplus value.")

Capital will substitute living labour-power by labour that is objectified in machinery if this increases surplus-value production. If an individual capital comes first with a more productive manner of producing in its branch, it will make "extra surplus-value", because it presses the "individual value" (SG 54) of the product under its "social value" (SG 54). The individual increase in the valorisation of value is here mediated by an increase in the "organic composition of capital" c/v (SG 56). What are the consequences for the social valorisation of value functioning as capital?

The "application of machinery to the production of surplus-value implies a contradiction which is immanent in it (SG 58), since of the two factors of the surplus-value created by a given amount of capital, one, the rate of surplus-value, cannot be increased, except by diminishing the other, the number of workmen. This contradiction comes to light, as soon as by the general application of machinery in a given industry, the value of the machine-produced commodity regulates the value of all commodities of the same sort" (CI 384), the "extra surplus-value vanishes, so soon as the new method of production has become general and has consequently caused the difference between the individual value of the cheapened commodity and its social value to vanish" (CI 302) (SG 55).

Socially, production of relative surplus-value by "displacement" of labour-power by machinery increases the rate of the valorisation of variable capital s/v, because it decreases the length of the necesssary labour-time. (The remaining labourers using the new machinery to produce the means of life work with greater productivity). But the increase in productivity is bought by an increased constant capital (SG 56) so that the rate of valorisation of the total capital advanced v/(c+v) might sink (SG 57).

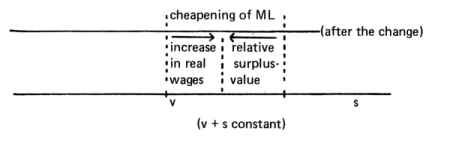

Production of relative surplus-value by means of an increase of the productivity of labour in the sector of the production of means of life (abbreviated: ML) that are consumed by the working class (SG 59) makes possible an increase in real wages and an increase of the rate of surplus-value at the same time:

It is a possible outcome of class struggle that capital gains no relative surplus-value by the introduction of machinery, the increase in productivity serving to provide the working class with more means of life. (It is only due to the above-mentioned assumption of presentation that this outcome is not focused upon.)

We can now go into a closer consideration of what Marx calls three "particular modes of producing relative surplus-value" (CI 304) (SG 60), i.e. increase of productivity by co-operation (chp. XIII) (SG 61), division of labour (chp. XIV) (SG 62), application of machinery (chp.XV) (SG 63). They are discussed one after the other although a capitalist process of production is characterized by co-operation, division of labour and application of machinery at the same time. This seems to be a general feature of "method" in Capital. But the particular problem with chapters XIII-XV (Vol.1), it seems to us, is, to discern features that are only of temporary importance in a certain phase of the historical development of capitalism - e.g. in the period of manufacture - from permanent, characteristic features of the capitalist mode of production.

Marx seemingly has in his mind to outline the development "both historically and conceptually" (cf. CI 305; "historisch und begrifflich" MEW 23, p.341). The above mentioned differences are not continually stated but we have to draw them out from this part of the presentation. Only in the analysis of the fully developed capitalist production process (SG 64) in "the automatic factory" (cf. CI 394ff) do we see the three methods systematically (i.e. conceptually) combined.

By co-operation is meant simply the working together of a number of labourers in the one labour-process. The combined working-day (SG 65) of a large number of co-operating labourers produces a greater quantity of use-values than the same labourers working separately i.e. it increases the productivity of labour. "Whether co-operation achieves an increase in productivity because it heightens the mechanical force of labour, or extends its sphere of action over a greater space, or contracts the field of production relatively to the scale of production or at the critical moment sets large masses of labour to work, or excites emulation between individuals and raises their animal spirits, or impresses on the similar operations carried on by a number of men the stamp of continuity and many-sidedness, or performs simultaneously different operations, or economises the means of production by use in common, or lends to individual labour the character of average social labour ... the special productive power of the combined working-day is ... the productive power of social labour. This power is due to co-operation itself" (CI 311 f). Co-operation is the general name of relative surplus-value production by way of adapting the subjective factor (labour-power) in the production process. Since it is capital which sets up a labour-process and inserts the labourer into it (SG 66), co-operation appears as a power that is immanent in capital.

Division of labour occurs both socially between different branches of industry and in detail within the factory of the capitalist (SG 67). The latter is a particular form of co-operation and has the following consequences: 1) the labourer who is employed to do one single task becomes expert at it; 2) division of labour requires a certain minimum scale of production (SG 69); 3) the knowledge and judgement of the labourer is required less and less as tasks become more and more fragmented (SG 68); 4) division of labour creates a dependence of one group of workers on another; and 5) the tricks of the trade (SG 70) which are acquired by a generation of labourers become established and are handed down to the next.

In the production of relative surplus-value by way of improving the objective factors in the labour-process i.e. the instruments of labour and raw materials, the application of natural science to production is all important (SG 71).

Marx specifies the elements of a machine (SG 72) as the motor mechanism, the transmitting mechanism and the tool or working machine. An essential characteristic of a machine is that it replaces the labourer who handles a single tool with a mechanism which, with a single motive power, sets in motion a number of tools. The natural sciences provide an adequate theory for building large and more sophisticated machines (SG 73) and a breakthrough in scientific theory from time to time leads to a revolution in value by developing wholly new types of machinery. An increase in productivity in one branch of industry calls forth a corresponding increase in those industries or spheres of industry which either supply the given sphere with raw materials or consume its product as means of production.

The social division of labour gives impetus to the improvement of means of transport and communication (SG 74) in order to move and co-ordinate the movements of immense quantities of materials.

The domination of the production process by machinery and the consequent freedom from consideration of the labouring of human hands enables the production process to be viewed in objective terms and for the problems caused by intransigent labourers to be solved. Machinery besides replacing labour, also dictates an intensity and regularity of work to its operatives (SG 76). The application of machinery leads to the real subordination of labour to capital in contrast to the formal subordination of labour to capital (SG 75).

Although, once discovered, a scientific result costs capital nothing (SG 77), the application generally requires the construction of intricate, enormous or technologically sophisticated machines (SG 78). The value condition for the introduction of machinery (SG 79) is that the value of the machine must be less than the price of the labour-power it replaces, e.g. if the machine lasts one year then its value must be less than the variable capital saved in the course of the year by laying-off labourers.

In Paper 2 we attempt to give a sketch of the systematic argument presented in this enormous "remainder" of Capital, Vol. I. Here, we try to point out which passages of Marx's text do not strictly - to the best of our present understanding - belong to the dialectic which unfolds the systematic presentation and may therefore be skipped in a systematic reading or at least postponed.

To put it bluntly, we regard Parts VI-VIII to be out of systematic order (although there might be other reasons for placing them in the first Volume of Capital, the only one published in Marx's lifetime).

Part VI should be incorporated in a properly worked out analysis of the class-struggle/competition over the distribution of the total social value which is mainly located by Marx in the fragment dealing with the revenue-forms and the "movement and dissolution of the whole shit in class-struggle" (" - der Klassenkampf als Schluß, worin sich die Bewegung und Auflösung der ganzen Scheiße auflöst...", in Marx's letter to Engels of April 30th 1868, Briefe über 'Das Kapital', Dietz Verlag Berlin 1954, p 172) - right at the end of Capital (Vol III).

Parts VII and VIII are one very bulky unit in the German original (as printed in Marx-Engels-Werke 23) labelled: "Abschnitt VII". The changed numbering of chapters and parts in the English version, published after Marx' death, are due to Engels.

Part VIII contains a lot of material which could be incorporated in the analysis of capitalist landed property and capitalist ground rent in Capital, Vol.III, Part VI. (This leaves aside chapters 30-32, the last one being as famous as it is unconnected with the preceding analysis. But have a look into it - only 3 pages - and form your own opinion.)

Part VII partly treats topics regarding capitalist reproduction (on a simple and extended scale) which could have either been dealt with as a resume of the analysis of absolute and relative surplus-value production (accumulation of surplus-value so that v is at least decreasing relatively to c) or left to be dealt with in greater detail at the end of Capital, Vol.II, where the production and circulation of the elements of production is focused upon.

Marx obviously tried to give an account of social reproduction at the end of each of the three volumes of Capital.

An alternative draft for the final part of Capital, Vol.1 is the text "Results of the Immediate Process of Production" (in Capital, Vol.1, Penguin/NLR edition 1976 as an appendix) which bears some affinity to Part V of Capital, Vol.1, which is, in our opinion, the end of the systematic presentation of the immediate process of capitalist production.

The question is what different features or aspects of social reproduction under capitalism are analysed in these subsequent parts. Marx gives a hint to that when he states: "we assume that the capitalist sells at their value the commodities he has produced, without concerning ourselves either about the new forms that capital assumes while in the sphere of circulation, or about the concrete conditions of reproduction hidden under these forms. On the other hand, we treat the capitalist producer as owner of the entire surplus-value, or, better perhaps, as the representative of all the sharers with him in the booty. We, therefore, first of all consider accumulation from an abstract point of view - i.e., as a mere moment in the immediate process of production." (CI 529f.)

But what precisely is the difference from the treatment of reproduction/ accumulation in Vol.II? The "new forms that capital assumes while in the sphere of circulation", i.e., 'circulating' and 'fixed capital' (SG 98) have not made the central categories of Vol. I, 'variable' and 'constant capital', invisible in Marx's reproduction-schemata of Vol.II. We therefore think that an extra treatment of the same matter in Vol.1 is superfluous (and that treatment of a different aspect of the matter can find its systematic place in Part V already). Our advice is to come back to the treatment of reproduction as given in Vol.1, Part VII (especially chapters 23 & 24) when discussing Paper 3 and Capital, Vol.II.

Chapter 25 "The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation" deals with the surplus-population produced by capitalist production and should be discussed in connection with Paper 5, where the revenue 'wage' is specifically analysed with its false semblance of qualitative equality with respect to the other forms of revenue. The workers made 'jobless' by capital and the class-struggle/competition over the distribution of the value newly created belong together. The industrial reserve army, by weakening the working-class, is a remedy for capital when the labourers' strong demands make capital sick by threatening its valorization (cf. CIII 251 on the underlying concept of "over-accumulation" or "absolute over-production" (cf. SG 142) ).

It might be helpful to notice that section 2 of chapter 25 contains material that is relevant in connection with "the tendency of the rate of profit to fall" - which, in contrast to Marx's treatment of it in Vol. III, Part III, we have sketched in Paper 2 already. For we believe that the main argument is presented within the analysis of relative surplus-value production already. (You can check this by referring to Capital, Vol.III, pp.212ff, where "gradual change in the composition of capital" (c/v cf. CI 583 & SG 56) is treated as a result ("... we have seen that it is a law of capitalist production...") and, besides CI 583 ("This law of the progressive increase in constant capital..."), Capital, Vol.1 pp.369ff. and 383f. where replacement of labourers by machinery is part of the systematic presentation of the increase in productivity in the context of relative surplus-value production.) So much for the part of Vol. I that we think does not properly fall into systematic order.

In considering the part which develops the systematic argument, we are left with Vol. I, chapter 7-18 (still well over 300 pages) which is Marx's analysis of the "immediate process of capitalist production", i.e. surplus-value production (looked at under the assumptions of presentation stated in Paper 2).

Central is chapter 7 section 2 "The production of surplus-value". (Skip the last bit on simple and skilled labour, which takes up objections raised on CI 46 "Some people might think…" and seemingly answered CI 51f. We think that this problematic belongs in the analysis of competition.) The two portions of the value of a capitalist commodity as pointed out in this section (cf. CI 183) are dealt with again in chapter 8 under the heading "Constant and Variable Capital", where the terms 'new value' and 'former values' (or: 'old value') are introduced and the distinction between "new value creation" and "old value preservation" (cf. CI 200) is made. Two other key terms, also immanent in the argument in chapter 7, i.e. 'necessary labour-time' and 'surplus labour-time' are introduced in chapter 9 "The Rate of Surplus-Value" (cf. CI 208ff), section 1. (Sections 2-4 may be skipped.)

Chapter 10, "The Working-Day", deals with absolute surplus-value production proper (the term 'absolute surplus-value' is introduced a fair bit later CI 299, cf. also CI 477f where 'absolute surplus-value' is used in a wider sense). The systematic argument is given in section 1. Sections 2-5 contain mainly historical illustrations (and could be skipped), whereas sections 6 & 7 deal with "The Struggle for the Normal Working-Day". With respect to the latter the problem arises whether state-activity can be incorporated into the analysis of the capitalist mode of production given Marx's plan of founding the theory of the bourgeois state on the analysis of the capitalist mode of production. Furthermore, the presentation of absolute surplus-value production treats labour-power as a second order commodity with a given price: a longer working-day is not paid with more money. (For the development of the wage-form, e.g. time-wage, under which a longer working-day is paid better and the relaxing of the assumption of presentation that real wages remain constant, cf. Paper 5).

Chapter 11 "Rate and Mass of Surplus-Value" introduces the term 'mass of surplus-value'. The structure of Capital, Vol I whose kernel is the presentation of absolute and relative surplus-value, is without doubt dominated by increasing surplus-value production in the sense of increasing the rate of exploitation. In CI 384 the contradiction immanent in the application of machinery could be spelt out in terms of rate versus mass of suplus-value and in CIII 251 it is pointed out explicitly that it is the increase of the mass of surplus-value which is decisive for the functioning of money as capital. The rate of surplus-value may remain unchanged with the application of machinery, at the same time as the mass of surplus-value increases by setting large masses of living labour to work.

The argument that the analysis of absolute surplus-value production is systematically prior to the analysis of relative surplus-value production is presented by Marx in a manner which tries to combine a systematic and a historical point: absolute surplus-value production is "independent of any change in the mode (=manner) of production" (CI 293) whereas relative surplus-value production is not. The latter depends on changes that help to increase the productivity of labour.

Chapter 12 is an introduction to Part IV "Production of Relative Surplus-Value"; the "particular modes of producing relative surplus-value" (CI 304) are subsequently dealt with in chapters 13-15. We conceive of co-operation, division of labour and application of machinery as three systematic aspects of the specific mode of capitalist production. The systematic presentation in this part of Capital is sometimes hard to follow, for Marx tries to give the development "both historically and logically" (CI 305). We suggest a purely systematic reading, sorting out all merely historical illustrations. Therefore we advise readers to concentrate in chapter 13 on co-operation as "the fundamental form of the capitalist mode of production" and not on "the elementary form of co-operation" as historically opposed to "the more developed forms of that mode of production" (CI 317) i.e. manufacture vs. modern industry. As a "fundamental form", co-operation is not something historically outdated and is not opposed to division of labour and application of machinery.

Chapter 14 bears both a systematic (or "logical") and a historical title: "Division of Labour and Manufacture". Once again we plead for focusing attention on a systematic reading. Division of labour characterizes capitalist production in general (and not only in a particular phase). For a systematic reading sections 4 & 5 appear to us the most interesting.

Chapter 15 "Machinery and Modern Industry" could be called the heart of Capital, Vol. I. We expand on "science and capitalist production", a topic which is central in the analysis of the application of machinery for relative surplus-value production, in the appendix "Science in Capital"… The application of machinery adds to "the productive forces resulting from co-operation and division of labour" (CI 365) by giving them an "objective skeleton" (CI 346, poorly translated as "framework"). We suggest reading the first five sections very carefully. Again it will take quite an effort to discern between the systematic argument and historically restricted illustrations of that argument.

This brings us finally to Part V, a summary or resume of the preceding presentation of absolute and relative surplus-value production. The central idea in chapter 16 is that absolute and relative surplus-value production are two systematically connected aspects of the capitalist production process, cf. CI 477ff. Marx puts a systematic distinction historically when contrasting "merely formal subjection of labour to capital" with "real subjection" (CI 478). The systematic point in the distinction of 'formal' vs. 'real subjection' depends on understanding absolute surplus-value production not as an historically preceding phase with respect to relative surplus-value production: "Relative surplus-value is absolute, since it compels the absolute prolongation of the working-day beyond the labour-time necessary to the existence of the labourer ... Absolute surplus-value is relative, since it makes necessary such a development of the productiveness of labour, as will allow of the necessary labour-time being confined to a portion of the working-day. But if we keep in mind the movement of surplus-value, this semblance of identity vanishes. Once the capitalist mode of production is established and becomes general, the difference between absolute and relative surplus-value makes itself felt, whenever there is a question of raising the rate of surplus-value." (CI 478f) In the following chapter 17 Marx points out that absolute and relative suplus-value production do not exclude each other.

At the end of chapter 16 Marx introduces the concept 'profit' as distinct from 'surplus-value'. In our view, this is not an anticipation of something which properly belongs to Vol. III, but that the "tendency of the rate of profit to fall" has its systematic place in the presentation here in Part V, Vol. I. Absolute and relative surplus-value production both lead to an increase of c/v simply because in a longer working-day as well as by working with greater productivity more raw material is used up. Looking at capital of given magnitude (simple reproduction) the greater expenditure of constant capital must be matched by expending less variable capital, cf. CI 383. Taking the accumulation of surplus-value as additional capital into consideration (extended reproduction), we still have the same result in relative terms, cf. CI 583ff.

It is worth noting that both absolute and relative surplus-value production are analysed as a "repetition of the process of production". This gives rise to the critical dissolution of the semblance inherent in "the isolated process" (CI 532), in which the capitalist appears - unquestioned - as the owner of capital as his property, into conceiving of capital as accumulated unpaid (CI 500) labour: "capitalist production ... under its aspect of a continuous connected process, of a process of reproduction, produces not only commodities, not only surplus-value, but it also produces and reproduces the capital relation; on the one side the capitalist, on the other the wage-labourer." (CI 542).

On Marx's view regarding what things will be like "after suppressing the capitalist form of reproduction" cf. CI 496 (and CIII 820).

Thus, for a systematic reading of the whole analysis of capital, we suggest moving on to Capital, Vol.II after having dealt with the resume of the analysis of absolute and relative surplus-value production in chapters 16-18.