Modern History of the Arab Countries. Vladimir Borisovich Lutsky 1969

Mohammed Ali’s failure in the Morea acted as a stimulus in his struggle for Syria and Palestine. He could not realise his plans for the creation of a great Arab Power without gaining possession of these two countries. Syria and Palestine protected Egypt from attacks from the east and served as a shield against the Turkish menace. The annexation of Syria would strengthen Mohammed Ali’s eastern borders and Egypt’s independence of the Porte. And Syria itself was a tempting prize. It was one of the richest provinces of the Ottoman Empire; it produced raw silk, wheat, wool, olive oil and valuable fruits, and it could also become a profitable market for Egypt’s growing industry.

Mohammed Ali was well aware of the Sultan’s weakness and knew he could force the Sultan to accept any conditions. With this in view, he began preparing for a struggle against the Porte. “In consequence of the unfortunate war of 1828-29,” wrote Marx, “the Porte had lost her prestige in the eyes of her own subjects. As usual with Oriental empires, when the paramount power is weakened, successful revolts of Pashas broke out. As early as October 1831, commenced the conflict between the Sultan and Mehemet Ali, the Pasha of Egypt, who had supported the Porte during the Greek insurrection.” [See Karl Marx, New York Daily Tribune, November 21, 1853.]

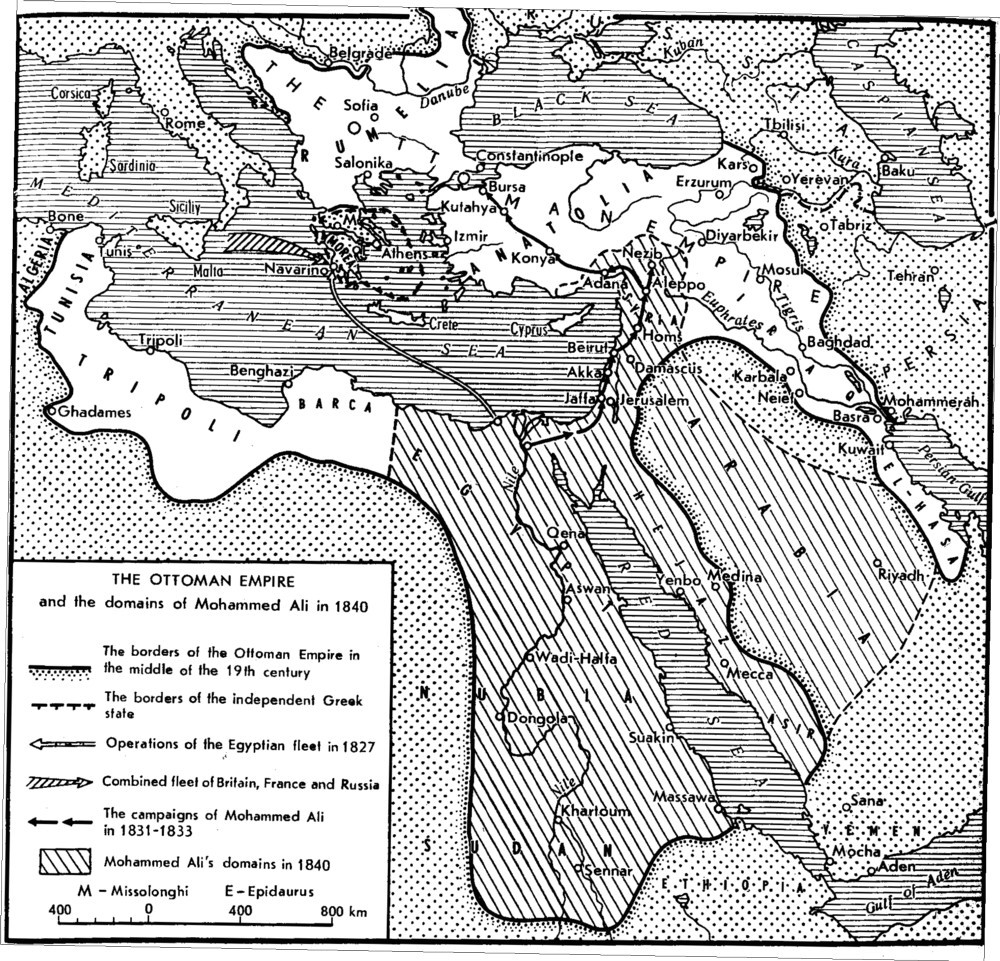

The war against the Porte began in 1831. There was a two-year delay because of the Franco-Egyptian plans for the conquest of North Africa. Mohammed Ali’s relations with his western neighbours were far from friendly and he had long nurtured the idea of seizing Maghreb. The conditions for such a conquest in 1829–30 seemed to be ripe. Relations with France, Mohammed Ali’s most important ally, had been normalised. In 1829, the French offered to finance a campaign against North Africa, to which the Pasha agreed. The Egyptians were to seize Tripoli, Tunisia and Algeria. Mohammed Ali formed a 40,000-strong army under the command of Ibrahim for the campaign against Africa, but demanded that, besides money, France should give him four 80-gun ships. The French refused and offered instead the assistance of their fleet. This arrangement was highly distasteful to Mohammed Ali, who wished to fight in Maghreb under the flag of Islam. In 1830, France put forward a new plan for a joint campaign. The Egyptians were to seize Tripoli and Tunisia, while France was to take Algeria. But Mohammed Ali rejected this plan, too. In the end he completely refused to participate in the Algerian campaign, which the French undertook by themselves, while Mohammed Ali devoted himself wholly to the events in Syria.

A dispute over six thousand Egyptian fellaheen, who had fled in 1831 to Palestine to avoid recruitment, served as an excuse for a revolt against the Sultan. The situation by this time had become quite strained. Mohammed Ali was openly refusing to obey the Porte. Having refused to participate in the Russo-Turkish war, he also refused to pay the indemnities agreed on by the Treaty of Adrianople. He felt he had paid tribute in blood in the Morea for many years in advance. Crete, he reasoned, could not compensate for the losses in the Morea, and he insisted on having Syria and Palestine too.

In the meanwhile, six thousand peasants fled from Egypt and found refuge in the domains of the Akka Pasha, Abdullah. Mohammed Ali demanded the return of the fugitives. Abdullah refused to give them up, declaring that, being the subjects of one ruler, they could live in any part of the Ottoman Empire they liked. Mohammed Ali then began military operations. In word, he remained loyal to the Sultan. He said he was not declaring war on the Porte, but on the Akka Pasha. In effect, the campaign against Abdullah developed into the Turco-Egyptian war.

The superiority of the Egyptians over the Turks made itself felt from the very outset. The Turkish army was in a state of complete decay. “The Turkish fleet was destroyed at Navarino,” Marx wrote, “the old organisation of the army was defeated by Mahmud, and a new one had not yet been created.” [Marx and Engels, Works, 2nd Russ. Ed., Vol. 28, p. 257.] The war against Russia weakened the Turkish army still further. The Egyptian army was well armed and disciplined. It had a series of victories to its credit in Arabia, the Sudan and Greece.

Moreover, military expenditure and indemnities had forced the Porte to raise taxes, and this was causing discontent among the masses. Peasant uprisings flared up throughout Turkey. The population of both the Arab and Turkish regions hailed the Egyptians as deliverers from the Sultan’s rule.

Turkey was unprepared for the war and showed signs of hesitation. For six months the Porte took no action. Only in March 1832, did the Turks really begin to prepare for the campaign, which had already begun. On April 23, 1832, the Sultan declared Mohammed Ali a rebel and relieved him of his duties. This was equal to a declaration of war.

The Egyptians made the best of the time factor. In October 1831, Ibrahim Pasha launched a campaign. Two or three weeks later, not having encountered any serious resistance, Egyptian troops occupied Gaza, Jaffa, Haifa and at the end of November 1831, advanced on Akka, the fortress which had once barred Napoleon’s path. After a six-month’s siege, (from November 26, 1831, to May 27, 1832) Akka fell. By this time the main forces of the Egyptians were far away in the north. The first big battle against the Turks took place on July 8, 1832, near the city of Homs. In this battle the Turks, commanded by nine pashas, were crushed. Over four thousand were killed or taken prisoner. They lost all their artillery and transports. The Egyptians lost only 100 men.

Having triumphed in Homs, Ibrahim occupied Hama and Aleppo and then headed for the Beilan mountain pass, situated between Antakiyah (Antioch) and Alexandretta. The pass was the key to the heart of the Ottoman Empire, Asia Minor, and here were stationed the main forces of the Turkish army, under the command of serdar-i-ekram, Hussein Pasha. On July 29, 1832, Ibrahim attacked and shattered the Turkish forces. Hussein Pasha fled to Adana with the remnants of his army, leaving the whole of Syria to the Egyptians.

The Egyptian troops entered Anatolia. They occupied Adana and then proceeded westwards. The Sultan dismissed Hussein Pasha and appointed Mohammed Reshid Pasha commander-in-chief. But this did not affect the course of the military operations. The third and last decisive battle of the war was waged on December 21, 1832, near Konya. The Turks threw their remaining 60,000 men against 30,000 Egyptians. Ibrahim proved a brilliant leader in the ensuing battle. Although outnumbered by two to one, he surrounded the Turks and utterly defeated them.

After the Battle of Konya, the Sultan had no troops left. The way to the empire’s capital lay open. The Egyptian advance guard soon entered Bursa: Istanbul was threatened.

The confused Sultan turned to the Powers for help. France openly supported Egypt and refused to help the Sultan. Russia openly sided with the Turks. England’s position was complicated. She was against Mohammed Ali, but feared the Turco-Egyptian conflict might lead to Russian intervention and consequently, to the strengthening of Russia’s influence or the division of the Ottoman Empire into two parts: the northern, which would be dependent on Russia, and the southern under Mohammed Ali, which would become a sphere of French influence. England, therefore, did all in her power to iron out the differences and preserve the “integrity” of the Ottoman Empire, where British influence was prevalent. England, in fact, bided her time and avoided rendering any direct aid to the Sultan.

In such circumstances there was nothing left for the Porte to do but to turn to Russia for help. Mohammed Ali’s success worried the Russians. According to the Russian Foreign Minister, Count Nesselrode, the aim of Russian intervention was to “save Constantinople from the possibility of a coup d’état, which would be a detriment to our interests and lead to the downfall of a weak, yet friendly state. Were they to substitute it for a stronger state under the French, it would be a source of all sorts of difficulties.” Russia, therefore, came out in defence of the empire’s integrity and the Sultan’s sovereignty.

On December 21, 1832, the Russian representative at Istanbul made an official offer of Russian military aid. General Muravyov set out with a special mission to the shores of the Bosporus, and from there proceeded to Egypt. He arrived at Alexandria on January 13, 1833, and communicated the demands of Nicholas I to Mohammed Ali. Mohammed Ali agreed to a compromise. He promised Muravyov to check the advance of his troops on Istanbul, stop military operations and recognise the supreme authority of the Sultan.

The panic in Istanbul, however, did not die down. Revolts instigated by Ibrahim Pasha’s agents flared up in Asia Minor. On February 2, 1833, the Egyptians occupied Kutahya. On February 3, Mahmud II made an official request for Russia’s help, and a Russian squadron entered the Bosporus on February 20, 1833. The landing of the 20,000-strong Russian expeditionary corps began on March 23, 1833. Its headquarters was situated on the Asian shores of the Bosporus at Unkiar-Skelessi, near the Sultan’s summer residence. At the same time, another Russian corps was sent to the Danube, to advance on the Turkish capital by land.

The Russian intervention seriously alarmed England and France. They hastened to reconcile Mohammed Ali with the Sultan so as to deprive the Russians of an excuse for keeping their troops on the Bosporus. To drive the point home, England and France carried out joint naval demonstrations off the coast of Egypt. On May 4, 1833, at Kutahya, a peace treaty was signed between Turkey and Egypt through the mediation of England and France.

Formally this was not a peace treaty in the legal sense of the word. The Sultan issued a unilateral firman, confirming Mohammed Ali’s right to Egypt, Crete, Arabia, and Sudan, and making him the ruler of Palestine, Syria and Cilicia. Mohammed Ali had to withdraw from Anatolia and recognise the Sultan’s suzerainty. By the will of the Powers, Egypt remained the vassal of the defeated Porte.

Russia’s intervention had saved Mahmud II. He retained his throne and empire, but he was still in a critical position. Both sides were dissatisfied with the Kutahya Treaty and regarded it as a truce. The Sultan was eager for revenge. Mohammed Ali wanted independence. A new conflict was inevitable, and Russian diplomacy did not fail to take advantage of this.

On the eve of the evacuation of the Russian troops, July 8, 1833, Turkey signed the famous eight-year Unkiar-Skelessi Treaty, which provided for the creation of a military alliance between Russia and Turkey. Russia undertook to send her troops to the Sultan’s aid “should the need arise.” In this connection Nesselrode remarked: “We now have a legal basis for an armed intervention in Turkey’s affairs.” Turkey undertook to close the Dardanelles to warships of all nations, whenever Russia demanded it.

The Munchengrätz Convention, signed on September 18, 1833, between Russia and Austria during a meeting of the emperors in Munchengrätz, was a supplement to the Unkiar-Skelessi Treaty. The Convention was soon signed by Prussia. The signatory Powers undertook:

“I. ... To support the existence of the Ottoman Empire under the present dynasty, and to use all effective means at their disposal.

“II. To oppose by common efforts any combination that may cause detriment to the rights of the supreme government in Turkey either by the establishment of an interim regency or a complete change of dynasty.”

Finally, the first secret clause stipulated that “the provisions of Article II should be applied specifically to the Pasha of Egypt ... to prevent the direct or indirect spread of his supreme power to the European provinces of the Ottoman Empire.”

In the end, British and French diplomacy paralysed the practical results of the Unkiar-Skelessi Treaty and the Munchengrätz Convention. These agreements, nevertheless, did constitute a serious obstacle to the realisation of Mohammed Ali’s plans and deprived him of the fruits of his victory in the first Syrian campaign.

The Turco-Egyptian war resulted in the formation of two states within the framework of the formally united Ottoman Empire. Mohammed Ali exercised control over Egypt, the Sudan, Syria, Palestine, Arabia, Cilicia and Crete, and only Anatolia, Iraq and a few regions of the Balkan Peninsula remained in the hands of the Sultan. Mohammed Ali’s empire was more densely populated, vaster, stronger and richer than that of Mahmud II. The situation was fraught with a new conflict which was not long in making itself felt.

The political plans of Mohammed Ali and his son Ibrahim, the supreme ruler of Syria, went very far. Both dreamed of creating a large independent Arab state.

“His real design is to establish an Arabian kingdom including all the countries in which Arabic is the language,” [George Antonius, The Arab Awakening, L., Hamilton, p. 31.] wrote Lord Palmerston about Mohammed Ali in 1833.

A French envoy, Baron de Boislecomte, who paid Ibrahim a visit at the time, related that Ibrahim made no secret of his intention to revive Arab national consciousness and restore Arab nationhood, to instil in the Arabs a real sense of patriotism and to associate them in the fullest measure in the government of the future empire. Baron de Boislecomte added that Ibrahim was active in spreading his ideas of national regeneration. In his proclamations he had frequently referred in stirring terms to the glorious periods of Arab history and had infected his troops with his own enthusiasm. He had surrounded himself with a staff who shared his ideas and worked for their dissemination.

However, the conditions for the consolidation of the Arab nation had not yet matured: the Arab bourgeoisie of Syria was still very weak; feudalism had not been liquidated. Ibrahim Pasha, who was a talented politician, made a careful study of the experience of the advanced countries of the time. He saw the tendencies of future development and tried to accelerate their realisation. He carried out a series of reforms in Syria, which, like the reforms of Mohammed Ali in Egypt, were aimed at the centralisation of the country, the liquidation of feudal arbitrary rule and separatism, and the creation of prerequisites for the development of capitalist relations.

First of all, Ibrahim tried to turn Syria into a granary of the future Arab empire. To check the decline of farming, he ruled that the fellaheen pay a fixed tax. He forbade arbitrary feudal extortions and exempted the newly ploughed land from taxation for many years. He settled Bedouins on abandoned land, forcing them to give up their nomadic way of life. Thus new villages were built and close to 15 thousand feddans of virgin land were brought under cultivation in the steppe between Damascus and Aleppo. During the first two years of Egyptian rule the area under cultivation rose from 2,000 to 7,000 feddans in the fertile Hauran Valley. The Turkish army had always been notorious for its marauding. But Ibrahim sent his troops on a campaign against the Turkish army, thereby putting an end to the continuous devastation of the Syrian crops.

The liquidation of the tax anarchy promoted the development of industry and trade. Now the merchants and the artisans had no need to fear for the safety of their property. They had no need to fear the plundering and blackmail of the Turkish pashas. They knew the exact amount of the tax they had to pay and could freely dispose of the remainder of the surplus value which they had collected. With a boldness hitherto unknown, they circulated and turned into capital the rotting treasures hidden from the covetous eyes of the pashas and derebeys. The custom houses were wrested from the tax-farmers and fixed customs duties were introduced. This policy, which was conducive to economic development, led to the growth of Syrian towns and foreign trade. “The liberty granted to trade by the Egyptians, gave new life to the seaports. Saida, Beirut and Tripoli became free markets where the mountaineers could exchange their silk and olive oil for wheat and European manufactured goods. Output in the Lebanon increased by at least one-third and the consumption of overseas goods doubled,” Russian consul Bazili wrote.

Roads inside the country and caravan routes through the desert linking Damascus with Baghdad were made safe. Transit trade expanded. British cloth was sent via Syria to Mesopotamia and Iran. Goods from India and Iran passed through Syria to Europe.

Ibrahim waged a fierce struggle against the Syrian feudal lords. Naturally, he could not destroy the feudal mode of production and the feudal class domination that went with it. But he strove to end feudal separatism, restrict the political rights of individual feudal rulers and replace the indocile seignieurs with men who would obey him absolutely. In the Lebanon, for instance, he depended on Emir Beshir II, who continued the war against other Lebanese feudal lords in the name of Ibrahim Pasha. In Nablus, Ibrahim depended on the Abd el-Hadi sheikhs in his struggle against the other sheikhs.

Ibrahim consolidated the central authority and reorganised the administration of the country along Egyptian lines. Syria, Palestine and Cilicia were divided into six provinces or mudiriyas headed by mudirs. Deputies of the central power (mutasallims) were appointed in each town. The sheikhs of the neighbouring villages were subordinate to the mutasallims. Each mutasallim headed a consultative organ, mejliss, or shura, which was formed from among the local landowners, merchants and clergy. The mejlisses were given the functions of civil courts. The highest judicial authority was in the hands of Ibrahim, who personally passed sentence on criminal and political cases after their preliminary consideration by the courts.

Educational reforms were also introduced during Egyptian rule. The first Lebanese printing house was founded in 1834 in Beirut. In the same year, Ibrahim initiated a wide programme of primary and secondary education. He established primary schools all over Syria and founded secondary colleges in Damascus, Aleppo and Antioch. The pupils were boarded at government expense. They wore uniforms and were given a strict military education as was the custom in Egyptian schools. The teaching was conducted in Arabic. The American traveller, George Antonius, related that the school director, the famous Clot Bey, received instructions to “inculcate a true sense of Arab national sentiment.” [George Antonius, op. cit., p. 40.]

Like Mohammed Ali, Ibrahim was known for his religious tolerance, which was an unusual trait among the Turkish pashas. Ibrahim freed the Arab Christians, in whose hands were concentrated the crafts and urban trade, from many humiliating restrictions forced on them by the Turks.

Although the reforms of Ibrahim Pasha promoted the growth of the productive forces and eased the conditions of the merchants, artisans and peasants, they evoked considerable discontent in Syria.

The feudal lords, whom Ibrahim had deprived of political privileges, were not the only ones in the country who showed signs of discontent. The Bedouin and mountain tribes, banned from the practice of highway robbery, were also dissatisfied. There was a sharp change in the mood of the peasants, who had also begun to show signs of discontent at Ibrahim’s reforms. It was they who had to bear the burden of his military plans. Realising that the Sultan had reconciled himself to the loss of Syria temporarily only and would attempt to recapture the province in the near future, Ibrahim undertook a number of defensive measures. He built fortresses, strengthened the mountain passes with fortifications, bought cannons and expanded the army. Ibrahim used the forced labour of the Syrian fellaheen, recruited from all over the country, to build the fortifications. Cannons were acquired at the expense of the same Syrian fellaheen, who had to pay higher taxes to the authorities each year. Ibrahim had restricted taxes in the first years of Egyptian rule, but the preparations for the war against Turkey made him change his policy. Finally, the ranks of the Egyptian regiments were swelled by the Syrian fellaheen, whom Ibrahim wearied with his endless recruitments. The recruitments evoked especial animosity, causing peasant disturbances and, in some districts, large uprisings.

In 1834, the first big peasant uprising against recruitments broke out in Palestine and soon spread almost over the whole country. The Egyptian punitive expedition sent to the Judaean Hills was wiped out and insurgents besieged Ibrahim in Jerusalem. Reinforcements from Egypt, led by Mohammed Ali, came to his help. Mohammed Ali personally supervised the reprisals against the rebels.

An uprising of the Druze peasants of Hauran and Anti Lebanon flared up at the end of 1837. For the first five years of Egyptian rule the Hauranians had been exempted from military service. When the term expired, the Egyptian authorities demanded recruits. The Hauranians then rose in rebellion and entrenched themselves in the lava field of El-Leja, a huge mountainous labyrinth, resembling a natural fortress. All the attempts of the Egyptians to storm El-Leja were unsuccessful. Those who managed to penetrate into the fortress were killed. Ibrahim continued to send greater numbers of troops trained in mountain warfare to El-Leja, but they were unable to overcome the small group of Druze peasants. lbrahim tried to overcome them by starvation, but still the peasants did not surrender. Ibrahim blew up the wells and filled the reservoirs with corpses. The Druzes drank the stagnant water. Only when Ibrahim poisoned the wells did the Druzes emerge from El-Leja. Even then, they did not surrender. They broke through the encirclement and continued to fight the Egyptians at the foot of Anti Lebanon, where they were eventually defeated and dispersed in the autumn of 1838.

The uncertain and ambiguous situation created by the Kutahya treaty of 1833 was a source of serious anxiety to Mohammed Ali. It was necessary to consolidate his gains legally, ensure the continuity of power and legalise Egypt’s independence. For many years Mohammed Ali had pressed for the recognition of his hereditary rights to his vast domains. In 1834, he turned to the Powers and in 1836–37, directly to the Porte, requesting a decision on the question of Egypt’s independence and the rights of his heirs. This brought no results. As usual, the Powers sided with the Porte. Feeling their support, the Sultan showed no inclination to give up the greater part of his empire. At the last resort he agreed to grant Mohammed Ali his hereditary rights to Egypt alone on the condition that the Egyptian Pasha give his other domains back to the Porte.

The Porte’s refusal to come to a peaceful settlement once again worsened Turco-Egyptian relations. Serious trouble was in the making. Awakened public opinion in the Arab countries, especially in Egypt, sided with Mohammed Ali. In 1838, the Ulema of Cairo declared their full support for the plans to grant Egypt independence. But the Powers, especially England, adopted a hostile attitude towards the question. England eyed the growth of Egypt’s might with anxiety. Egypt was a serious obstacle to the establishment of British domination over the coastal regions in the East, a menace to British positions in the Persian Gulf, and the chief impediment to the development of Britain’s imperial communications and commerce.

The famous Anglo-Turkish Trade Treaty was signed on August 16, 1838. It was very advantageous to England and paved the way for the conversion of the Ottoman Empire into an agricultural and raw material appendage of the foreign powers. In exchange for a certain raising of tariffs, the treaty abolished the monopolies of the Turkish treasury on the exchange of various sorts of raw material. Thus the British exporters could buy raw materials at low prices either directly from the producers or through their commercial agents, skirting the treasury.

The British bourgeoisie pressed for the extension of the treaty to cover the entire Ottoman Empire, including Mohammed Ali’s domains. By steering round Mohammed Ali’s monopolies, it hoped to buy Egyptian cotton, Syrian wool and silk at low prices. It wanted to capture the import markets of Egypt and Syria, which were then dominated by France. But Mohammed Ali flatly refused to have the conditions of the treaty applied to his domains.

Mohammed Ali was also against England’s plans for the creation of an English waterway on the Euphrates (for the transfer of mail and goods from the mouth of the Orontes to the Euphrates by caravan or a specially built canal and further downstream along the Euphrates to Basra). He also objected to various schemes for the construction of a canal across the Isthmus of Suez.

Mohammed Ali’s reconquest of Nejd and the Egyptians’ emergence on the Persian Gulf roused British displeasure, while Egypt was troubled by British expansion in the Persian Gulf and South Arabia.

High policy – the Powers’ struggle for hegemony in the Near East and, in particular, England’s desire to weaken French and Russian positions in the East – aggravated the conflict. England fought against both Mohammed Ali and France. But by this time France had captured the greater part of Algeria and occupied a dominating position in Syria and Egypt as Mohammed Ali’s ally. By fighting against Mohammed Ali, the British hoped to consolidate the Sultan’s position and change the balance of forces in his favour. In this way they intended to make the Unkiar-Skelessi Treaty ineffective and at the same time bring to naught Russian influence in Turkey.

Such were the reasons that prompted England’s decision to remove Mohammed Ali and prevent a settlement of the Turco-Egyptian conflict. England objected to the recognition of Egypt’s independence and acted as the fourth guarantor of the Ottoman Empire’s integrity, although officially she had not signed the Munchengrätz Convention.

Feeling the support of the four Powers, Turkey began preparing feverishly for a war. She mobilised a 100,000-strong army, which she concentrated near the Syrian border. England backed the Turks and urged them to fight. Her attitude made an armed conflict inevitable.

The Turkish troops crossed the Euphrates and invaded Mohammed Ali’s domains on April 21, 1839. They were utterly defeated, however, in the first decisive battle at Nezib. The battle began early on June 24, 1839. The Egyptians, led by Ibrahim Pasha, occupied the heights, overlooking the Turkish positions and opened fire. After an hour of fighting, the Egyptian artillery silenced the Turkish batteries and cleared the path for Ibrahim’s cavalry, whose headlong attack sealed the Turkish army’s fate. For the second time in seven years, the way to the Turkish capital opened before Ibrahim. On June 30, 1839, six days after the battle at Nezib, Sultan Mahmud II died. Two weeks later the whole Ottoman fleet under Ahmed Fauzi Pasha went over to Mohammed Ali’s side. In the space of three weeks Turkey had lost her sovereignty, her army and her fleet, wrote Guizot. Once again Egypt was victorious.

Ibrahim, however, had no intention of undertaking a campaign against Istanbul. Acting on the advice of his father and France, Ibrahim restricted himself to the occupation of Urfa and Marash. Nowhere did the Egyptians cross the Taurus, for they had no desire to provoke a new Russian intervention. Ibrahim chose instead to come to terms with the Porte. He was ready to limit himself to the recognition of the hereditary rights of Mohammed Ali’s dynasty to Egypt and her domains. The Porte’s defeat made it all the more willing to accept any terms Ibrahim might propose.

This was certainly not the outcome of the war that England and the other signatory Powers of the Munchengrätz Convention had expected. They had reckoned without the growing strength of Egypt. On July 27, 1839, they presented a joint note to Turkey in which they urged her to suspend all definite decisions made without their concurrence, pending the effect of their interest in its welfare. The note was signed by the four Powers of the anti-Egyptian bloc (England, Austria, Prussia and Russia) and also by France, who presented herself as “Egypt’s ally and friend.” France decided to operate jointly with the Powers so as to avoid isolation and guard the interests of the French bourgeoisie in Egypt and Syria.

The talks between the Powers on the fate of Turkey and Egypt lasted for a whole year. France urged the Powers to come to a peaceful settlement and give Mohammed Ali the hereditary pashaliks of Egypt and Syria. Austria and Prussia agreed to surrender Egypt and part of Syria. Russia, who was anxious to maintain the status quo and the Unkiar-Skelessi Treaty, was indifferent to the territorial question. England proposed to wrest Syria from Mohammed Ali.

The talks continued without a break. The Permanent Conference of Ambassadors sat in London and discussed the Eastern Question. Diplomats and journalists raised a clamour over the “Eastern crisis.” But what they forgot to mention was that the crisis was of their own making, that but for their interference all the differences between Turkey and Egypt would have been settled.

France, acting behind the back of the four Powers of the anti-Egyptian coalition, persuaded Turkey and Egypt to sign an agreement in May 1840, according to which the Sultan made Mohammed Ali the hereditary ruler of Egypt and Syria.

The Powers decided to wreck the agreement. They took advantage of the discontent in Syria and Palestine to instigate several revolts against the Egyptians. The Lebanese uprising of May 1840 was particularly formidable.

Bazili, an eyewitness of the event, wrote in this connection: “Mutiny raged throughout the Christian regions of the Lebanon. A few thousand mountaineers, half of them armed with weapons and half with shovels and wooden staffs, descended from the mountains with the intention of capturing Beirut. They were met by a barrage of fire from the castles, which, however, caused no damage to the mountaineers, who took what cover was offered by the terrain. They occupied the whole neighbourhood and began killing the soldiers, and looted all state property, but they did not lay hands on private individuals ... In their proclamations they pledged loyalty to the Sultan, poured out their grudges against the Egyptians, and spoke of Mohammed Ali and Ibrahim Pasha in biblical terms, portraying them as the worthy heirs of the pharaohs who had oppressed the chosen people.”

Ibrahim easily suppressed the uprising, for it was poorly organised and confined mainly to the Christian areas of the Lebanon. Mountain villages were pillaged and burnt and the leaders of the uprising were banished to Sennar (the Sudan).

The failure of the Lebanese uprising coincided with the beginning of the Powers’ open intervention. The London Conference of Ambassadors came to an agreement in the summer of 1840 on the conditions for a settlement of the Eastern Question. England, Austria, Prussia, Russia and Turkey signed a convention on July 15, 1840, which decided the fate of Mohammed Ali and his domains.

The conclusion of the London Convention of 1840 was a great success for British diplomacy. Russia was restricted in her actions. France was completely isolated and England came near to realising her cherished dream. She had secured the support of the three Powers and the supervision of the struggle against Mohammed Ali.

On August 19, 1840, the Powers demanded that Mohammed Ali accept the conditions of the London Convention, which boiled down to the following:

Mohammed Ali declined the Powers’ ultimatum and declared his intention of “upholding by the sword what had been won by the sword.” In response, England and Austria along with Turkey began military operations. British and Austrian squadrons appeared off Syria. The squadrons included steamships, which were being used for the first time in naval warfare. On September 11, 1840, a British squadron under the command of Charles Napier, landed a force (1,500 British soldiers and 7,000-8,000 Turks) north of Beirut, where the British and Austrians began to arm the mountaineers and supply them with instructors and money. Rebellion against the Egyptians broke out with new force in the Lebanon. The Egyptian army was in difficulties.

Mohammed Ali had counted on France’s help, but France did nothing but rattle her sabres. The bellicose campaign in the French press did not frighten England. The French Government realised that armed assistance to Egypt would mean a large-scale European war. Moreover, France would have had to fight single-handed against Prussia on the Rhine and against Britain on the seas. Rather than incur the risk of a European war, France decided to leave Egypt in the lurch. In March 1840, the French Government was taken over by Thiers, an advocate of a union with Egypt and of resolute actions. On October 8, 1840, Thiers sent a threatening note to the Powers, warning them that he would not permit Mohammed Ali’s banishment. Three weeks later, however, on October 29, 1840, he resigned. The new cabinet of Soult and Guizot did not intend to fight over Egypt and hastened to come to an agreement with the Powers concerning Mohammed Ali.

In the meantime, the position of Ibrahim’s army was becoming increasingly difficult. Ibrahim’s forces, scattered all over Syria, were suffering from disease and undernourishment. They were trapped by cross-fire. The guerrillas had cut their communication lines. The Anglo-Austrian squadron was blockading the ports and shelling the Syrian coast, while on land the British landing party and the insurgents were dealing heavy blows at the Egyptian army. In the first few weeks, the insurgents, with the help of the British fleet, occupied Jubeil, Batrun, Sur, Saida and Haifa on the Syrian coast. New arms transports flowed into the heart of the country from the occupied towns.

On October 10, 1840, Ibrahim’s forces were shattered by the insurgents and Napier’s landing party in a relatively big battle near Beirut. The Egyptians were compelled to withdraw from the coastal and mountain regions of the Lebanon. Beirut, Latakia and Alexandretta went to the enemy. Emir Beshir II, Mohammed Ali’s ally, surrendered to the British, who banished him to Malta, replacing him with his own cousin Qassim, who had fought on the British side.

Akka, the chief stronghold of the Egyptians, fell on November 3, 1840, after it had been bombarded from the sea. A small British detachment captured the city and then marched on Jerusalem. Anti-Egyptian uprisings flared up in Palestine. They spread to Galilee, Nablus, Hebron and to the southern parts of Syria, Biqa’a and Anti Lebanon. Further resistance was useless.

The British squadron, under the command of Napier, approached Alexandria in November 1840. Napier offered Mohammed Ali an ultimatum, threatening to open fire on the main base of the Egyptian fleet.

The Syrian uprising, the defeat of the Egyptian army in Syria and Palestine, France’s position and the menace to Egypt itself shook Mohammed Ali’s iron will. He realised that the Egyptians could not stand against the world’s four biggest Powers and accepted Napier’s terms.

On November 27, 1840, under the muzzles of British guns, the Egyptians signed the convention proposed by Napier. In return for a guarantee of the hereditary pashalik of Egypt, Mohammed Ali undertook to evacuate Syria and Palestine completely and to restore the captured Turkish fleet.

Mohammed Ali gave the order for the immediate evacuation of Syria and Palestine. Ibrahim Pasha and his forces left Damascus on December 29, 1840, and headed for the south, but by this time the British had occupied Jerusalem and barred the Egyptian army’s retreat. Ibrahim had to retreat through the Transjordanian steppes and deserts. Out of 60,000 Egyptian soldiers, who had started out on the campaign, only 24,000 reached Gaza. The others died on the way of hunger, thirst, cold, disease and guerrilla raids.

The Egyptian Question was settled on June 1, 1841, by a special hatti-sherif (the noble rescript) after long talks between the Powers. Mohammed Ali retained the hereditary pashaliks of Egypt and the Sudan, but gave the Sultan back Syria, Palestine, Cilicia, Arabia and Crete. He reduced his army to 18,000 men. He was deprived of the right to appoint generals in his army and to build warships. He gave Turkey back her fleet. He acknowledged himself the Sultan’s vassal and pledged to pay a large tribute into the Sultan’s treasury.

Having destroyed the Egyptian army and fleet, the Powers, as Marx put it, made impotent “the only man... to replace a ‘dressed up turban’ by a real head.” [New York Daily Tribune, July 25, 1853.] They dealt a serious blow to the plans for Egyptian independence and were responsible for the conversion of Egypt into a British colony. Formally, Egypt’s dependence on the Porte was strengthened, but actually the Porte lost Egypt in 1841. It passed completely under British control. From then on, as Marx and Engels wrote, “Egypt belongs more to the English than to anybody else.” [New York Daily Tribune, April 7, 1853.]

Having placed the Nile valley under her control, England simultaneously gained a foothold in the Dardanelles. On her insistence, the Unkiar-Skelessi Treaty, which had expired in 1841, was not renewed. In its place, five European Powers and Turkey signed a new Convention on the Straits on July 13, 1841, in London, according to which the Bosporus and the Dardanelles were closed to all warships, including those of Russia.

Last updated: 28 July 2020