Works of Auguste Blanqui 1866

Source: Auguste Blanqui. Instruction pour une prise d'armes. L'Éternité per les astres, hypthèse astronomique et autres textes, Société encyclopédique français, Editions de la Tête de Feuilles. 1972;

Transcribed: for www.marxists.org, by Andy Blunden;

Translated: by Andy Blunden, 2003;

CopyLeft: Creative Commons (Attribute & ShareAlike) marxists.org 2004.

This program is purely military and leaves entirely to the side the political and social question, which this isn’t the place for: besides, it goes without saying, that the revolution must (effectively work against the tyranny of the capital, and) reconstitute society on the basis of justice.

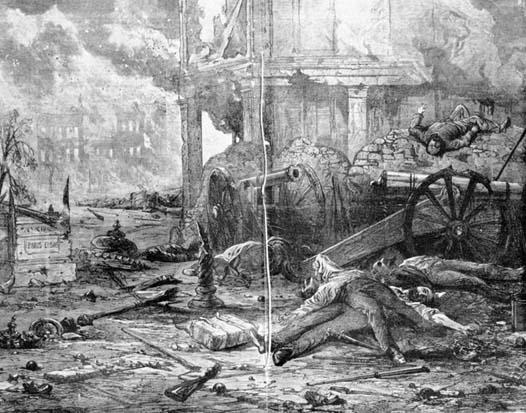

A Parisian insurrection which repeats the old mistakes no longer has any chance of success today.

In 1830, popular fervor alone was enough to bring down a power surprised and terrified by an armed insurrection, an extraordinary event, which had one chance in a thousand.

That was good once. The lesson was learnt by the government, which remained monarchical and counter-revolutionary, although it was the result of a revolution. They began to study street warfare, and the natural superiority of art and discipline over inexperience and confusion was soon re-established.

However, it will be said, in 1848 the people triumphed using the methods of 1830. So be it. But let us not have any illusions! The victory of February [1830] was nothing but a stroke of luck. If Louis-Philippe had seriously defended himself, supremacy would have remained with the uniforms.

The proof is the June days. It is here that one can see how disastrous were the tactics, or rather the absence of tactics of the insurrection. Never had they had such a favourable position: ten chances against one.

On one side, the Government in total anarchy, demoralized troops: on the other, all the workers were solid and almost certain of success. Why did they succumb? Owing to lack of organisation. To account for their defeat, it is enough to analyze their strategy.

The uprising breaks out. At once, in the workers’ districts, the barricades go up here and there, aimlessly, at a multitude of points.

Five, ten, twenty, thirty, fifty men, brought together by chance, the majority without weapons, they start to overturn carriages, dig up paving stones and pile them up to block the roads, sometimes in the middle of a street, more often at intersections. Many of these barriers would present hardly any obstacle to the cavalry.

Sometimes, after the crude beginnings of preparing their defenses, the builders leave to go in the search of rifles and ammunition.

In June, one could count more than sixty barricades; about thirty or so alone carried the burdens of the battle. Of the others, nineteen or twenty did not fire a shot. From there, glorious bulletins made a lot of noise about the removal of fifty barricades, where there was not a soul.

While some are tearing the paving stones from the streets, other small bands are disarming the corps de garde or seizing gunpowder and weapons from the armories. All this is done without coordination or direction, at the mercy of individual imagination.

Little by little, however, a certain number of barricades, higher, stronger, better built, are chosen by defenders, who concentrate there. It is not calculation, but chance which determines the site of these principal fortifications. Just a few, by a kind of military inspiration rather than design, occupy the large intersections.

During this first period of the insurrection, the troops, on their side, gather. The generals receive and study the police reports. They take good care not to let their detachments venture out without unquestionable data, for fear of failure which would demoralize the soldiers. As soon as they have determined the positions of the insurrectionists, they mass the regiments at various points which will constitute from now on the base of their operations.

Both armies are in position. Let us look at their manoeuvres. Here will be laid bare the vice of popular tactics, the undoubted cause of the disaster.

Neither direction nor general command, not even coordination between the combatants. Each barricade has its particular group, more or less numerous, but always isolated. Whether it numbers ten or one hundred men, it does not maintain any communication with the other positions. Often there is not even a leader to direct the defence, and if there is, his influence is next to nil. The fighters do whatever comes into their head. They stay, they leave, they return, according to their good pleasure. In the evening, they go to sleep.

In consequence of these continual comings and goings, the number of citizens remaining at the barricades varies rapidly by a third, a half, sometimes by three quarters. Nobody can count on anybody. From this grows distrust of their capacity to succeed and thus, discouragement.

Nothing is known of what is happening elsewhere and they do not trouble themselves further. Rumors circulate, some black, some rosy. They listen peaceably to the cannons and the gunfire, while drinking at the wine merchants. As for sending relief to the positions under attack, there is not even the thought of it. “Let each defends his post, and all will be well,” say the strongest. This singular reasoning is because the majority of the insurgents fight in their own district, a capital fault which has disastrous consequences, in particular the denunciation by their neighbors, after the defeat.

For with such a system, defeat is certain. It comes at the end in the person of two or three regiments which fall upon the barricade and crush their few remaining defenders. The whole battle is just the monotonous repetition of this invariable maneuver. While the insurrectionists smoke their pipes behind heaps of paving stones, the enemy successively concentrates all his forces against one point, then on to a second, a third, a fourth, and thereby exterminates the insurrection one bit at a time.

The popular fighters do not take care to counter this easy task. Each group awaits its turn philosophically and would not venture to run to the aid of a neighbor in danger. No! “He will defend his post; he cannot give up his post.”

This is how one perishes through absurdity!

When, thanks to such grave faults, the great Parisian revolt of 1848 was shattered like glass by the most pitiful of governments, what catastrophe should we not fear if we begin again with the same stupidity, before a savage militarism, which now has in its service the recent conquests of science and technology: railways, the electric telegraph, rifled cannon, the breech-loading rifles?

For example, something we should not count as one of the new advantages of the enemy is the strategic thoroughfares which now furrow the city in all the directions. They are feared, but wrongly. There is nothing about them to be worried about. Far from having created a danger for the insurrection, as people think, on the contrary they offer a mixture of disadvantages and advantages for the two parties. If the troops circulate with more ease along them, on the other hand they are also heavily exposed and in the open.

Such streets are unusable under gunfire. Moreover, balconies are miniature bastions, providing lines of fire on their flanks, which ordinary windows do not. Lastly, these long straight avenues deserve perfectly the name of boulevard that is given to them. They are indeed true boulevards, which constitute the natural front of a very great strength.

The weapon par excellence in street warfare is the rifle. The cannon makes more noise than effect. Artillery could have serious impact only by the use of incendiaries. But such an atrocity, employed systematically on a large scale, would soon turn against its authors and would be to their loss.

The grenade, which people have the bad habit of calling a bomb, is generally secondary, and subject besides to a mass of disadvantages. It consumes a lot of powder for little effect, is very dangerous to handle, has no range and can only be used from windows. Paving stones do almost as much harm but are not so expensive. The workers do not have money to waste.

For the interior of houses, the revolver and the bayonet, sword, sabre and dagger. In a boarding house, a pike or eight-foot long halberd would triumph over the bayonet.

The army has only two great advantages over the people: the breech-loading rifle and organisation. This last especially is immense, irresistible. Fortunately one can deprive him of this advantage, and in this case ascendancy passes to the side of the insurrection.

In civil disorders, with rare exceptions soldiers march only with loathing, by force and brandy. They would like to be elsewhere and more often look behind than ahead. But an iron hand retains them as slaves and victims of a pitiless discipline; without any affection for authority, they obey only fear and are lacking in any initiative. A detachment which is cut off is a lost detachment. The commanders are not unaware of this, and worry above all to maintain communication between all their forces. This need cancels out a portion of their manpower.

In the popular ranks, there is nothing like this. There one fights for an idea. There only volunteers are found, and what drives them is enthusiasm, not fear. Superior to the adversary in devotion, they are much more still in intelligence. They have the upper hand over him morally and even physically, by conviction, strength, fertility of resources, promptness of body and spirit, they have both the head and the heart. No troop in the world is the equal of these elite men.

So what do they lack in order to vanquish? They lack the unity and coherence which, by having them all contribute to the same goal, fosters all those qualities which isolation renders impotent. They lack organisation. Without it, they haven’t got a chance. Organisation is victory; dispersion is death.

June 1848 put this truth beyond question. What would be the case today? With the old methods, the entire people would succumb should the troops decide to hold out, and they will hold out, so long as they see before them only irregular forces, without direction. On the other hand, the very sight of a Parisian army in good order operating according to tactical regulations would strike the soldiers dumb and make them drop their resistance.

A military organisation, especially when it has to be improvised on the battle field, is no small business for our party. It presupposes a commander-in-chief and, up to a certain point, the usual series of officers of all ranks. Where to find this personnel? Revolutionary and socialist middle-class men are rare and the few that there are fight only the war of the pen. These gentlemen imagine they can turn the world upside down with their books and their newspapers, and for sixteen years they have scribbled as far as the eye can see, without being tired out by their difficulties; with an equine patience, they suffer the bit, the saddle and the riding crop, and never a kick! Damn that! Return the blows? That’s for louts.

These heroes of the inkstand profess the same scorn for the sword as officers for their slices of bread and butter. They do not seem to suspect that force is the only guarantee of freedom; that people are slaves wherever the citizens are ignorant of art of soldiery and give up the privilege to a caste or a corporate body.

In the republics of antiquity, among the Greeks and Romans, everyone knew and practiced the art of war. The professional soldier was an unknown species. Cicero was a general, Caesar a lawyer. By taking off the toga and donning the uniform, they would begin as colonel or captain and would acquit themselves ably. As long as it is not the same in France, we will remain civilians fit to be cut down at mercy of the officer caste.

Thousands of the educated young, working-class and bourgeois tremble under a detested yoke. To break it, do they think of taking up the sword? No! The pen, always the pen, only the pen. Why the one and not the other, as the duty of a republican requires? In times of tyranny, to write is fine, to fight is better, when the enslaved pen remains powerless. Eh bien, no! They publish a pamphlet, then go into prison, but they do not think of opening a manual of military tactics, to learn there in twenty-four hours the trade which constitutes all the power of our oppressors, and which would put in our hands our revenge and their punishment.

But what is the good of these complaints? it is the stupid practice of our time to deplore something instead of doing something about it. Jeremiads are the fashion. Jeremiah poses in all the attitudes, he cries, whips, he dogmatizes, he dominates, he thunders, the plague of all plagues. Let us leave these elegizers, these grave-diggers of freedom! The duty of a revolutionist is the fight, the fight come what may, the fight until death.

Do the cadres lack for the forming of an army? Eh bien! We must improvise them on the ground even, in the course of action. The people of Paris will provide all the elements, former soldiers, ex-national guards. Their scarcity will oblige us to reduce to a minimum the number of officers and NCOs. But no matter. The zeal, the ardor, the intelligence of the volunteers, will make up for this deficit.

The essential thing is to organize. No more of these tumultuous risings, with ten thousand isolated heads, acting at random, in disorder, without any overall design, each in their local area and acting according to their own whim! No more of these ill-conceived and badly made barricades, which waste time, encumber the streets, and block circulation, as necessary to one party as the other. As much as the troops, the Republican must have freedom of his movements.

No useless racing about, hurly-burly, clamoring! Every minute and every step is equally precious. Above all, do not hole up in our own district as the insurrectionists have never failed to do, to their great harm. This mania, after having caused the defeat, facilitates proscriptions. We must cure ourselves of this under penalty of catastrophe.