Erich Wollenberg’s

The Red Army

PART FOUR

Four Years Of Civil War And Intervention

[See also Appendix II: Chronicle of The Civil War.]

Chapter Three

Historical Analogies.

The armed conflict against internal counter-revolution began even before the seizure of power by the Bolshevists. When, in August 1917, General Kornilov marched on Petrograd, his main blow was aimed at the rising socialist  proletariat rather than the vacillating bourgeois democracy. But the hard struggle for self-preservation and the consolidation and amplification of the October Revolution, which lasted nearly four years, did not begin until after the easily won victory of that October of 1917.

proletariat rather than the vacillating bourgeois democracy. But the hard struggle for self-preservation and the consolidation and amplification of the October Revolution, which lasted nearly four years, did not begin until after the easily won victory of that October of 1917.

The Civil War, which tortured the land to its very marrow and claimed untold victims, was not a phenomenon peculiar to the Russian Revolution. “History hows no instance of a revolution which may be considered an accomplished fact when it has proved successful, or which will allow the rebels to rest on their laurels when it is over.” In these words Lenin did no more than utter a historical truth which is as old as classes and class wars.

There is always something fascinating about historical analogies between revolutions. Comparisons between the October Revolution and the French Revolution are frequently drawn; the revolutionary wars each country was forced to wage after overthrowing the old régime, and their onset and ending, are reduced all too readily to a common denominator. But we must “use such analogies with the greatest caution,” as Trotsky rightly pointed out in his Military Doctrine (1921), “for otherwise,” he continues, “the superficial resemblances may induce us to forget the material differences.” Trotsky’s criticism is all the more instructive since he has failed to follow his own advice in that he is now led to draw an unwary comparison between Stalinism and Bonapartism on the ground of superficial resemblances. Therein he overlooks the fact that the material and social-economic causes of Bonapartism were to be found in the destruction of small-scale production, whereas Stalinism has risen to power on an economic basis of State monopolies.

In the work already quoted, Trotsky writes: “When discussing revolutionary wars, we are most frequently influenced by memories of the wars of the French Revolution. Therein we forget that at the end of the eighteenth century France was the richest and most civilized country of the European continent, whereas twentieth-century Russia was the poorest and most backward European land. The revolutionary task of the French Army was far more superficial in character than the revolutionary tasks before us now. In those days the main objective was the overthrow of the ‘tyrants’ and the abolition or modification of feudal serfdom. Our mission, on the other hand, is the complete destruction of exploitation and class oppression.,,

The absolute and relative poverty and backwardness of Russia combined with the material and socialpolitical substance of the proletarian revolution to stamp their own particular impress on the Russian Civil War. The great majority of the Russian population belonged to the lower middle classes, while according to the last pre-War statistics 86.5 of this population lived on the land, against only 13.5 in the towns.

“Russia is so large and so variegated,” wrote Lenin in a polemic against the ‘left’ communists in May 1918, “that the most varying types of social and economic conditions are intertwined one with another. We have (1) the patriarchal peasant economic system, which to a very large extent is natural economy; (2) the economic system of the petty trader (which includes the majority of the peasants who sell bread); (3) the private economic system of capitalism; (4) State capitalism; (5) socialism (since the victory of the October Revolution). The main social-economic war will develop into a struggle of the lower middle classes plus private capitalism, against State capitalism and socialism.”

A survey of this social-economic structure of Russia reveals the futility of historical comparisons between the objectives, tendencies of development and degenerative manifestations (Thermidor!) of the French Revolution and the October Revolution.

From the Peace of Brest-Litovsk to the Entente’s Intervention

After the victories of the Revolution in Petrograd and Moscow the authority of the Soviet Government overflowed the whole vast realm like a mighty stream that carries everything with it. The Soviets in the towns and on the land came under Bolshevist leadership, the old officials were hunted out of office, the workers took possession of the factories, and the peasants seized the estates of the Crown, the Church, and the landed proprietors. When manifestations of resistance appeared locally, they were dealt with by small shock troops of Red Guards or detachments of pro-revolution soldiers sent from the capital or acting on their own initiative. This elemental force of the first revolutionary wave caused a panic in the camp of the counter-revolutionists, and a temporary paralysis of all forces hostile to the Revolution.

The only opposition that still held out was the Rada of the Ukraine, which was more or less akin to the Kerensky Government in its political aspect, but possessed strong separatist Ukrainian-nationalistic features. Even after the victory of the proletarian revolution, the centuries of oppression by the Great Russians proved an obstacle to an independent class movement in the ranks of the proletariat of the races formerly oppressed.

The Rada still held sway in Kiev, the old Ukrainian capital situated in the midst of the plains, but a Central Executive Committee of the Soviets had been formed at Kharkov, the centre of the Ukrainian industrial and mining area, and was gradually extending its power westward. Both these bodies sent peace delegations to Brest-Litovsk, but during the negotiations Soviet troops occupied Kiev on February 8, 1918, and the Rada government fled to Zhitomir. The representatives of German and Austro-Hungarian imperialism then concluded a treaty with this landless government, which, as Trotsky remarked, had “no territory for its basis except the citadel of Brest-Litovsk.” They thought by this step to put pressure on the Russian Soviet delegation; moreover, there were reasons of home politics which made them anxious to give their peoples a ‘peace’ as a stimulant to further “prosecution of the war to a final victory.”

For the moment this German manuvre could do nothing to influence the fate of the Rada. The Ukraine was occupied by Red troops led by Antonov-Ovseyenko and Georgi Piatakov, the latter becoming head of the first Ukrainian Soviet Government, which was then formed.

The Rumanians occupied Bessarabia during the Brest-Litovsk negotiations. In February they were heavily defeated by Red Guard troops led by Colonel Muraviov, who was destined later to turn traitor when fighting against the Czechoslovaks. In this campaign Chinese labour corps fighting on the Soviet side won distinction; they were organized and led by a twentyone-year-old Jewish student from Kishinev named Yakir, while another successful leader of Red forces on the Bessarabian front was Uborevitch, who had become a member of the Bolshevist Party in 1917.

Under pressure of their defeat the Rumanians made a peace offer which envisaged the complete evacuation of Bessarabia. Peace was concluded on this basis on March 8, 1918. Then the Germans occupied the Ukraine, and, feeling secure under the protection of Wilhelm’s bayonets, the Rumanians remained in Bessarabia. Uborevitch threw his troops against the advancing Germans, but after fierce fighting they were dispersed. He was wounded and taken prisoner, but managed to escape before he had fully recovered from his injuries.

Meanwhile the Red Guards suppressed two revolts organized by counter-revolutionary officers.

A large number of officers had left the army some time before its break-up. They gathered together in the Don area, which was mainly agricultural, and at Orenburg in the Urals. The latter district provided a very favourable basis of operations for a counter-revolution, because the majority of the workers were small owners and landed proprietors, while the mixture of many nationalities was another asset. The most important non-Russian racial group was that of the Bashkirs, who had been involved in conflicts with the Russians on the question of land ownership from time immemorial. The White generals were able to exploit these racial antagonisms for their own purposes.

In the Orenburg steppes the Cossack Hetman Dutov raised White volunteer formations composed of officers of the old army and Ural Cossacks. But he was defeated by local Red Guard forces, led by the Bolshevist metalworker Medvedyev, who won the nickname of ‘Marshal Forward’ by the celerity of his military operations and from the slogan ‘Forward’ which he always wrote in his daily orders and invariably uttered when he led the Red Guards personally into action. He is known to-day as Marshal Blcher, and we may add that in 1918 he was the first to be decorated with the Order of the Red Flag.

The concentration of White Guard officer formations under Generals Kornilov and Kaledin in the Don area was a far greater menace to the new Soviet Government. Since the Rada Government was not yet expelled from the Ukraine, Kaledin was in a position to cut Russia off from her richest coalfields by a successful advance, as well as from her European granary if he managed to effect a junction with the Rada. Moreover, Kaledin had ample man-power at his disposal for recruiting purposes in the Cossacks of the Don steppes; but, on the other hand, the social structure of these Cossacks was by no means a homogeneous one. Of their 2,000,000 population 1,800,000 were peasants, including 500,000 landless peasants. Therein, and in the great proletarian oasis of the steppes known as the Don basin, lay the great weakness of the Whites in the Don area.

The main Red plan of operations aimed at driving a wedge between the Ukraine and the Don and thrusting forward as far as Rostov on the Sea of Azov in order to annihilate each set of opponents separately. Under the leadership of Antonov-Ovseyenko this task was fulfilled in the shortest possible time.

Three Red Guard detachments, led by Sivers, Sablin and Petrov, converged on Rostov, which was occupied on March 8, 1918. Kaledin had committed suicide a month previously, when he lost faith in his power to win the Don Cossacks over to his counter-revolution. General Kornilov, who after his death assumed the supreme command, managed to escape after the capture of Rostov and the dispersal of the White Guard volunteers.

The Reds who defeated the officers’ volunteer formations were a strangely improvised force, in which worker detachments of Red Guards fought in tactical co-operation with formations composed of the remnants of old regulars. The main fighting took place along the line of the railway, where the Reds were forced to advance in three successive groups in order to coordinate the varying reliability of their different units. In the van was an armoured train, behind which followed the Red Guards, while the formations from the remnants of the old army brought up the rear.

The suppression of both these officers’ revolts proved that the counter-revolutionaries were not in a position to overthrow the power of the Soviet by means of internal force alone. Henceforth they made every endeavour to obtain armed assistance from abroad; that is, the Russian counter-revolutionaries became ‘native auxiliaries’ of the imperialist powers. Their patriotism was thereby shown up as treason against national interests in favour of foreign imperialism. The words of Karl Marx, written in 1871 in his Civil War in France, came true; as he then said: “Class rule is no longer in a position to disguise itself in a national uniform; all nationalist governments are united against the proletariat.”

After the expulsion of the Rada from Kiev and the crushing of Dutov and Kaledin, the middle of February 1918 saw almost the whole of Russia in the hands of the Soviets. But the following weeks were to reveal the instability of the political basis on which the dictatorship of the proletariat rested.

In the second half of February the forces of German imperialism occupied the Baltic States and suppressed the Revolution there with much bloodshed. At the same time they began to advance into the Ukraine for reasons which we find enumerated in the diary of General Hoffmann, who wrote on February 17, 1918: “To-morrow we are going to begin hostilities against the Bolshevists. There is no other alternative, for otherwise these fellows will kill off the Ukrainians, Finns and Baits, raise a new revolutionary army at their leisure, and do their dirty work all over Europe.”

In pursuance of this ‘European mission’ of German imperialism Kiev was occupied; two weeks later it was the turn of Odessa; in April the Germans were in Kharkov. The chiefs of the Red Army could despatch only 15,000 fighting men against the enemy’s twentynine infantry divisions, and four and a half cavalry divisions, which constitute an army of 200-250,000 men.

The Germans set up the Tsarist General Skoropadski as Hetman; with the help of German bayonets he established a bloody military dictatorship. The Red Guards evacuated the Ukraine almost without a fight, but an illegal Bolshevist revolutionary committee remained behind in Kiev, where it functioned under the leadership of Georgi Piatakov, whose elder brother Leonid had directed the illegal Bolshevist military work in January 1918, during the régime of the Rada, until he was arrested and murdered after bestial tortures. But Georgi Piatakov was destined to be shot by Stalin nineteen years later.

Among the members of this illegal revolutionary committee were Skripnik, Satonsky, Aussem and Bubnov. (Skripnik was People’s Commissar for the Ukraine in 1937, when he committed suicide just before his arrest.) The functions of this committee comprised disorganization of the enemy’s lines of communication, revolutionary propaganda among the armies of occupation, and preparation for revolts.

The German troops occupied the Ukraine and the whole southern portion of European Russia, advancing as far as the coasts of the Sea of Azov.

The Beginning of the Entente’s Intervention

The end of May 1918, saw the beginning of an adventure that took place along a 3,000-kilometre stretch of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Its scope extended from Irkutsk on Lake Baikal to Samara on the Volga, and it provided the sparks that were to set alight the internal counter-revolution.

During the World War there had come into existence in Russia a Czechoslovak Legion, composed mainly of Austrian prisoners of war of Czech nationality. This body of men was in the Ukraine at the time of the October Revolution, and promptly declared its neutrality.’

Jaroslav Hashek, who was later destined to win universal fame with his cultural-historical war novel The Good Soldier Schweik,

fought in their ranks.

The Czechs retreated to Soviet Russian soil when the Germans occupied the Ukraine. It was agreed with the Soviet Government that they should be entrained on the Trans-Siberian Railway and sent to Vladivostok, where they could take ship for France. But the occupation of this port by the Japanese induced the Soviet authorities to change their plans, for they feared that a junction of armed Czech forces with the Japanese might lead to a strengthening of the anti-Soviet front in Siberia. They therefore opened fresh negotiations with the Czechs and French, with a view to arranging for the Legion to march to Archangeisk. Then, at the end of May 1918 the Czechoslovak Legion rose up in insurrection against the Soviet authorities.

Soviet rule collapsed along the whole length of the Trans-Siberian Railway, in the vast area of the European Volga basin and as far as the heart of Siberia. The Czechoslovaks occupied almost simultaneously Samara on the Volga, Chelyanbinsk in the Urals and Novo-Nikolayevsk (now known as Novo-Sibirsk) when marching on the Trans-Siberian Railway in three columns. Their numbers were not great, amounting only to some 40,000 men in all, so that the weakness of the Soviet Government and the fickleness of the Russian peasantry and lower middle classes are amply demonstrated by the fact that forces so numerically feeble were able to take control of a region extending from the Volga to the Ob and thence to Lake Baikal, with a stretch of 3,000 kilometres of railway for their strategical basis.

General Stefanik, destined later to be the first Minister for War in the Czechoslovak Republic, supplied the international background for the Legion’s action in a speech he made to the Czech soldiers during his sojourn in Siberia. “I can assure you,” he said, “that the Entente will take responsibility for the fighting in which our Czechoslovak soldiers are now engaged, and that even the French Socialists have voted the money for the upkeep of the Czechoslovak troops in Siberia. This time I can guarantee that the Entente’s action will take concrete form. As far as my information goes, the Allies themselves are about to begin hostilities against the Soviet forces, and will operate mainly in southern Russia, which General Berthelot is going to occupy with five divisions drawn from the Salonika and Rumanian fronts. At the same time the Entente troops in Murmansk will be reinforced.”

Dr. Benes, the former Foreign Minister and present President of the Czechoslovak Republic, expresses similar views in his Memoirs, in which he says: “The problem of our Legion became an important element in the Allied policy and plan of campaign.”

The ‘Government of Siberia,’ which was established at Omsk, and the ‘Government of the Constituents’ at Samara came into existence on the strength of the Czechoslovak insurrection. Both these governments were of a petty-bourgeois democratic nature.

Another Civil War front was formed at the same time in southern Russia. When the Germans advanced into the Don area which the Red Guards had cleared of Kaledin’s White formations, the Cossacks rose up against the Soviets. A White Don Army was formed under the General Krasnov who was arrested after his attempt to suppress the rising in Petrograd in October 1917, and subsequently released on giving his word of honour to undertake no further action against the Soviets. The Kuban area, which comprised the rich corn-growing steppes north of the Caucasus, where so many Cossacks lived, was also lost to the Soviets, the leader of the White Guard revolt there being General Denikin.

The Russian bourgeoisie had recovered from its panic. It soon abandoned defensive action and everywhere took the offensive. The Red Guards were unable to cope with the regular military forces of the Whites. They retreated almost without a fight. When they went into action, they were defeated after a brief resistance. The plight of the Red forces is depicted as follows by Putna in his work on the Civil War:

’When Kazan yielded on August 6, 1918, to the combined blows of the Czechs and White Russians, our weak forces fled after their dispersal in a north-westerly direction. They fled as men flee after a decisive-so it then seemed-defeat which can never be counterbalanced.”

The deadly peril threatening the Soviet Republic caused the views of Lenin and Trotsky in favour of a centralized army assisted by military specialists to prevail over the adherents of guerilla warfare. In fact the Czechoslovak Legion was in some measure, though unintentionally, the cause of the birth of the Red Army. The Soviet Government proceeded to a mass mobilization; the men called up were equipped, armed, drafted into formations and trained in the railway-trains and on the march. The Revolutionary Council of War gave orders for a temporary evacuation of the Tsaritsyn sector on the southern front, since General Krasnov, who was still in process of organizing his White armies, threatened no immediate danger. K. Voroshilov, who was in command on that sector, refused to execute this order, and was supported in his insubordination by Stalin, who was attached to the southern army as a member of the local Revolutionary Council of War. The subsequent failure of the southern army on the battlefield of Simbirsk prevented the complete defeat of the Whites; according to a statement made by Tuchachevsky in 1922 in his capacity of director of the War Academy, this caused the Civil War to be prolonged by two years.

The confidence of the Russian proletariat in its ability to put up a successful resistance against the attacks of regular White formations was badly shaken. Matters were made worse by the treachery of Colonel Muraviov, which fell like a thunderbolt on a Red front in process of formation.

It was then that Trotsky took personal charge of operations at Sviyazhsk, near Kazan. On September 10, 1918, Putna took this town, and on September 12 the 1st Red Army, commanded by Tuchachevsky, won a decisive victory over the allied Czechoslovak and White Russian forces, recovered Simbirsk, and began the series of quick operations that freed the middle Volga area from the Whites.

The battle of Simbirsk was the first great victory won by the regular Red Army, Trotsky wrote as follows:

“That day was a noteworthy date in the history of the Red Army. At once we felt firm ground under our feet. The time of our first helpless efforts was over; thenceforth we were able to fight and win.”

The Climax of the Civil War

But the situation of the Soviet Republic still remained critical after the battle of Simbirsk. The Entente had landed English and American troops in Murmansk and Archangelsk in July and August. The Far East was occupied; an Allied army was formed under the command of a Japanese general, with whom the English General Knox was associated. It was made up of two Japanese divisions, 7,000 Americans, two English battalions and 3,000 French and Italians.

According to the statistics of the Russian General Staff, the interventionist forces in February 1919 reached a total of 300,000 men. Of these, 50,000 men composed the northern army, while Franco-Greek troops to the number of 20,000 along with 7,000 Americans, occupied the Black Sea coast. There were 40,000 men in the Finnish sector and another 37,000 in Estonia and Latvia. The Polish forces numbered 64,000 and the Czechoslovaks 40,000. The Japanese sent three divisions, and finally there were the 31,000 German Baits. These figures do not include the sailors of the British and French Fleets in the Baltic and Black Seas.

The Civil War ravaged Russia for three years, during which victory fluctuated from one side to the other. It often looked as if the Soviet Republic was bound to be broken within a few weeks; there were also moments when hopes took the concrete form of a proletarian revolution hastening westwards in quick, bold leaps. Twice Bolshevism knocked at the gates of Central Europe-in the spring of 1919 and in the Polish campaign of 1920.

When the German armies of occupation that were disintegrating under Bolshevist influence streamed homewards after the triumph of the November Revolution in Germany and Austro-Hungary, the Red Army began to prepare itself for its mission of carrying the banner of the international proletarian revolution into the lands of the West. Those were the days when Lenin wrote:

“The Russian proletariat will understand that the time is close at hand when it must make its greatest sacrifices on behalf of internationalism. The day is approaching when circumstances will require us to give assistance against Anglo-French imperialism, to the German nation that has freed itself from its own imperialism. Therefore, let us begin our preparations without delay. Let us show that the workers of Russia can work all the more energetically, fight with greater self-sacrifice, and give their lives more readily when a revolution is at stake that is not merely a Russian affair but an affair of the international workers of the world.”

In the spring of 1919 direct military intervention by the Red Army in the international arena of the class war appeared to be only a matter of days. In Hungary and Bavaria the workers had seized power ; the Hungarian Red Army was engaged on a victorious offensive. After reconquering the Ukraine, the Russian Red Army advanced in the direction of Carpathian Russia, where whole districts came under the control of Soviet guerilla forces. Every hour decreased the distance separating the Russian revolutionary forces advancing westward and those of the Hungarian pressing forward in a northeasterly direction.

Then the attack launched by Horthy’s White Guards and their allied forces compelled the Hungarian Reds to suspend their advance in the north-east and throw all their forces on to their south-western front. At the same time the Russian Red Army troops marching towards Carpathian Russia had to be hastily transferred to the new eastern front that came into existence on the Volga and the southern front in the Ukraine and Don areas. Admiral Kolchak had succeeded in overthrowing the petty-bourgeois democratic ‘Government of Siberia,’ and his armies were approaching the Volga, while General Denikin, who had assumed the supreme command of all White Guard formations in southern Russia, was advancing against central Russia from his base at Kuban.

Denikin occupied the Don area and eastern Ukraine; his troops pressed forward to Orel, which is only 382 kilometres distant from Moscow. In the Ukraine a peasant revolt broke out in the rear of the Red forces. The White counter-revolution derived advantage from the accentuation of the class struggle in the villages, while the peasants rebelled against the compulsory requisitions of their produce.

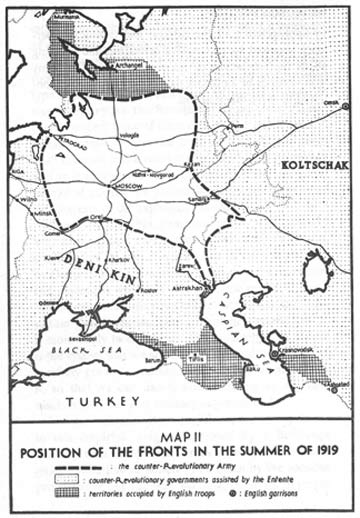

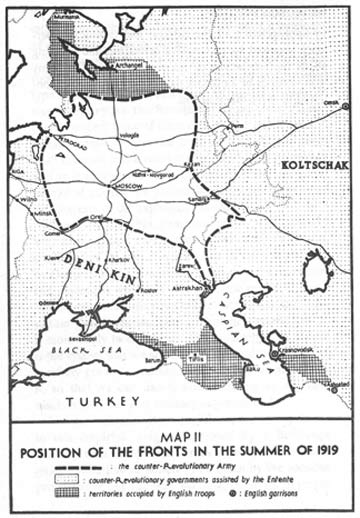

By the end of April the situation had undergone a radical change to the disadvantage of the Soviet Government. More than five-sixths of Russian territory were in the hands of the Whites, whose forces moved onward from east and south towards Moscow like an irresistible steam-roller. (See Map 1.)

In March 1919, Frunse became Commander-in-Chief of the troops opposing Kolchak on the eastern front; in the middle of April the 5th Red Army, commanded by Tuchachevsky, was added to his forces. Tuchachevsky was in charge of the counterstroke, and he concentrated 36,000 of the 60,000 men comprising the eastern army in Busulug, a small town in the central Volga area, not far from Samara, leaving the 700kilometre stretch of front held only by a weak line.

He thus gained a decisive tactical superiority at the centre of gravity he had chosen. He broke through the White front and rolled it up. After the battle of Busulug he initiated an advance that is almost unparalleled in military history, for it started from the Volga area, crossed the Urals, and then continued right through Asiatic Russia until it reached Vladivostok. His forces covered a distance of over 8,000 kilometres under conditions of practically continuous action.

On August 13, 1919, Frunse diverged into Turkestan with a portion of the Eastern Red Army, while Tuchachevsky continued the pursuit of Kolchak with the 2nd and 5th Armies. He took Omsk on November 14; Tomsk fell to him on December 22, and Krasnoyarsk (3,217 kilometres by rail from Samara) on January 6, 1920. For 247 days the Red forces thus covered an average of 13 kilometres a day, during which time they were not merely engaged in continuous fighting, but had also to scale the steep slopes of the Ural range and face the icy cold of a Siberian winter.

In January 1920, Kolchak was cut off from the Pacific coast by a rebellion that broke out in his rear at Irkutsk. The Czechoslovak Legion concluded an armistice with the Reds and handed over the gold of the Russian treasury, which they had captured in Kazan, in return for a free passage. Kolchak shot himself before the Soviet troops marched into Irkutsk.

In January Tuchachevsky was recalled from the eastern front to central Russia, where he was given charge of the operations against Denikin, who had occupied Kiev in the summer of the previous year while the Red forces were chasing Kolchak’s men across the Urals. Denikin’s cavalry, led by General Mammontov, had broken through the Red lines and reached Tambov, 471 kilometres south of Moscow. They laid waste all the country through which the Soviet troops would have to march.

The Soviet Government proceeded to create its own powerful cavalry forces. The first mounted troops had been raised as far back as the summer and autumn of 1918 by the Revolutionary Council of the southern army (Stalin, Yegorov and Voroshilov) from Budyonny’s guerilla troops, but Trotsky had always so far opposed the employment of cavalry in the Civil War, because it had to be recruited mainly from Cossacks, whose former privileged position made them unreliable.

But now Trotsky hurled his slogan, at the masses: “Proletarians, to horse!” Voroshilov was attached as commissar to Budyonny, the commander of the first cavalry forces. Therewith he was deprived of his independent command, and the Revolutionary Council of War thought they had found occupation for his individualistic guerilla tendencies which would keep him out of mischief.

October 9, 1919, was the date of the Red counteroffensive against Orel, which was captured by Uborevitch. The very first engagements proved Budyonny’s horsemen to be the superiors of the White cavalry, while the Ukrainian peasantry went over to the Soviet side once more, since they realized that a Denikin victory would mean the return of the former landed proprietors. Makhno’s guerilla forces effected a junction with the Red Army and advanced against Taganrog, on the Sea of Azov, where Denikin had his headquarters.

The seeds of decay were sown in Denikin’s army when he resorted to conscription in the summer of 1919.

Lenin foresaw the consequences of this step when he stated on July 4, 1919:

“A general mobilization will finish Denikin off, just as it finished off Kolchak. So long as his army was a class one, consisting only of volunteers of an antisocialist character, it was strong and reliable. He was certainly in a position to raise forces more quickly when he instituted compulsory military levies, but the greater the size of his army, the less class-conscious it was, and the weaker it became. The peasants conscripted into Denikin’s forces will serve him in the same way as the Siberian peasants served Kolchak, that is to say, they will disorganize his army completely.”

Denikin had just started a counter-offensive from the lower Don area when Tuchachevsky took over the supreme command of the southern army. The Whites were able to book some initial successes; then Tuchachevsky executed a deep turning movement which put him in a position to attack Denikin’s right flank at Tikhoryetsk. Denikin was forced to a disorderly retreat, and could only manage to put some remnants of his army on board ship at Novorossiisk, where they were despatched to join Wrangel in the Crimea. Thus the Red forces led by Tuchachevsky liquidated Soviet Russia’s two most dangerous opponents, Kolchak and Denikin.

In October 1919, Trotsky commanded the forces which beat off General Yudenich’s attack on Petrograd. A ‘Government of the North-West’ had been formed in the country to the north-west of the town under the protectorate of the British General March; this body had concluded an agreement with Estonia, whose independence it recognized. General Yudenich, who commanded the armies of the ‘Government of the North-West,’ had troops under his control which included 70,000 ‘eaters,’ but only 20,000 fighters. He was accompanied by no fewer than fifty-three former Tsarist generals, all of whom aspired to posts and received occupation commensurate with their rank. But when Yudenich’s army was defeated in October 1919, the ‘Government of the North-West’ ceased to exist, while the British Fleet, on which he relied for support, left him in the lurch, and the Estonians did the same. The remnants of the White forces fled into Estonia, where they were interned.

In February and March 1920, the forces of the Red Army suppressed the ‘Government of the North’ established in Archangelsk and Murmansk under the protection of English and American forces commanded by General Miller. Consequently the spring of 1920 saw the liberation of Soviet Russia from the encircling ring of hostile armies, the only foes remaining to be dealt with being the forces of General Wrangel, which held out in the Crimea. This area was not reconquered until after the termination of the Polish campaign, when Frunse accomplished the task.

The year 1920 was taken up by the Polish campaign, which is the subject of another chapter. Red forces occupied Georgia in February 1921, and the Kronstadt revolt broke out in the following March. The forces of Baron Ungern Sternberg in the Far East were annihilated in the autumn of 1921, while in October of the same year the pressure exercised by the Red Armies under Uborevitch compelled the Japanese and Americans composing the remaining Entente forces, to evacuate Vladivostok. Therewith the four years of Civil War came to an end.

The Intervention Fiasco

Fourteen States’ sent forces to Russia to suppress the Socialist Revolution. They included the world’s principal Great Powers-Britain, France, America and Japan-which had just succeeded in defeating German imperialism. With them were associated Czechoslovakia, Greece, Poland, Latvia, Finland, Estonia, Yugoslavia, Rumania, Lithuania and Turkey, while we must also include the Germans, who were active in the Ukraine in 1918 and in the Baltic States in 1919. Yet the Bolshevists triumphed over all this array of forces.

The interventionist Powers were divided among themselves by a clash of interests, and could therefore form no homogeneous plan for the conquest of Russia. If Poland had thought fit to attack at the time when Denikin controlled southern Russia and was on the march to Moscow, the Soviets would have been finished, but the reactionary Poles were not interested in southern Russia. Denikin’s forces had to be defeated before Poland chose to attack Soviet Russia in support of her Ukrainian vassal, Petliura.

The lack of unity in the camp of the interventionist Powers was one cause of the non-success of their intervention. The other cause may be found in the ugly mood prevailing among the peoples of those lands.

Clemenceau desired to suppress the Soviets by force of arms, but his own sailors, led by Marty, struck his weapons out of his hands. Curzon and Churchill launched an appeal for a crusade against Bolshevism, but the British workers opposed it, and Lloyd George adopted a vacillating attitude. Although the interventionist Powers invaded Russian soil with their White forces, the Soviets had allies of their own in the enemy’s countries. We need only cite the eloquent complaints which Churchill-then British Minister for War-made in his speech at the banquet of the Anglo-Russian Club on July 17, 1919:

“The great success achieved by our assistance shows that we could have effected a complete restoration in Russia by now, if the five victorious Great Powers had given strong and disinterested support from the very beginning. But there are among us a considerable number of people who would be unfeignedly glad to see Kolchak and Denikin, their forces, and all who espouse their cause, beaten and subjected to the Bolshevist Government. They would rejoice to see Lenin, Trotsky and their strange obscure band of Jewish anarchists and adventurers occupy the mighty throne of the Tsars without resistance or rivals, and add the new tyranny of their subversive ideas to the despotic methods of the old régime.”

Denikin was the last card on which the Allies staked their hopes. In the middle of April 1919, they were giving support to Kolchak, but his defeat ‘disappointed’ them. On April 24 Clemenceau sent Kolchak a telegram, in which he assured him that Denikin would be able to hold his ground as soon as he received help from the Entente, while the British, French and Rumanian forces would occupy southern Russia and the Poles would threaten sufficiently serious danger to the Bolshevists from the west. The French statesman therefore advised Kolchak to continue his offensive against Moscow and try to make contact with Denikin on his left wing.

This telegram must have been but a poor consolation to Kolchak, whose forced marches at that time were not directed towards Moscow, but rather towards the Urals. The last official British assistance received by the Whites was a sum of £14,500,000 given to Denikin. Churchill sent the following telegram to Kolchak about this sum:

“Some time ago the British Government decided to concentrate their assistance on General Denikin’s front. I am happy to inform you that the Cabinet has agreed on my recommendation to send General Denikin the sum of fourteen and a half million pounds for arms and equipment. The Cabinet is also of my opinion that it would be the most sensible plan to support General Denikin because he is close to Moscow and has occupied the corn and coal-mining centres.”

Lloyd George vacillated, but did not become definitely anti-interventionist until the fiasco of intervention was manifest. From the memorandum which he sent to the Versailles Council of Four on March 25, 1919, we may cite the following resounding trumpet-blast:

“The greatest danger I perceive in the present situation is the possibility of Germany uniting her destiny with that of the Bolshevists and placing her wealth, intellect and great organizing capacity at the disposal of the men who dream of conquering the world for Bolshevism by force of arms. This danger is no idle fancy. If Germany goes over to Spartacism, she will inevitably link her fate with that of the Bolshevists. If that takes place, all eastern Europe will be drawn into the maelstrom of the Bolshevist Revolution, and a year hence we shall find ourselves opposed by nearly 3,000,000 men who will be welded by German generals and German instructors into a gigantic army equipped with German machine-guns and ready to undertake an offensive against western Europe.”

But the same trumpet sounded a retreat on November 17, 1919, after the heavy defeats inflicted on Denikin and Wrangel. When discussing the Russian question in the House of Commons on that day, Lloyd George said:

“Whenever the armies have marched beyond a certain point in their attacks on Bolshevism, they have failed. It is perfectly obvious that this country, with the enormous burdens cast upon it by the War, cannot undertake the responsibility of financing civil war in Russia indefinitely. Our first concern must be for our own people.”

The “concern for our own people” was due to the opposition manifested by British workers and soldiers to the anti-socialist intervention. This opposition, in fact, was the decisive reason for its complete failure. On December 6, 1919, three weeks after Lloyd George’s speech in the House of Commons, Lenin said to the 7th Soviet Congress:

“What is the miracle which enabled the Soviets to carry on two years of obstinate warfare, first against the German imperialism then deemed omnipotent, and later against Entente imperialism, and this despite our backwardness, poverty and war-weariness? We deprived the Entente of its soldiers. The victory we won when we forced the withdrawal of English and French troops was the most decisive success we have ever achieved against the Entente. We vanquished their numerical and technical superiority by virtue of the solidarity shown by the workers against imperialist governments.”

The intervention was a fiasco because its attempt to incite the internal forces of counter-revolution was carried out with insufficient means. When, therefore,

the internal counter-revolution ‘failed’ and the Allies were ‘disappointed,’ they were forced to disappoint their White Russian confederates, and so the intervention broke down.

Some Military-Political Problems

When appraising the military value of the operations in the Civil War, we must beware of mechanical comparison with the standards set by the World War or application of the experiences of the Russian Civil War to future wars fought out between modern mechanized armies.

The number of actual combatants in the Civil War was relatively small in comparison with those who took part in the World War. ‘Mass armies’ of 100, to 150,000 men were the largest forces which fought on either side in the Civil War. The statistics of the Red Army’s General Staff show that the White Guard forces fighting on Russian soil in the summer of 1919, i.e. at the time when they made their greatest efforts, did not number more than 500,000 infantry, 100,000 cavalry, 2,800 machine-guns and 700 cannon. This total of 600,000 men was distributed over three or four theatres of war completely separated from one another.

In view of the better military training and leadership of the Whites, and, moreover, of the higher percentage of experienced officers and N.C.O.s in their ranks provided by a corps of trained men, it was obvious that

the Reds could only win if they had the ‘bigger battalions’ on their side. The Red Higher Command realized the possibility of exploiting the advantage of fighting on inner lines and bringing a numerical superiority to bear on the enemy at the crucial point, as we may see from the example afforded by operations in the summer of 1919, when 172,000 men were concentrated on the southern front against Denikin’s 152,000. The Red numerical superiority was even more pronounced in the final operations against Wrangel in the Crimea, when Frunse’s troops were reinforced by formations brought from the Polish front, so that he was able to take the field with 143,000 men and 500 guns against Wrangel’s 37,220 men and 213 guns. In March 1919, when the forces opposing each other at Samara, on the eastern front, were more or less equal in numbers (111,000 Reds with 379 guns against 113,000 Whites with 200 guns), the Reds were forced to retreat until the arrival of Tuchachevsky’s 5th Army gave them the numerical superiority needed for victory.

This fact does nothing to detract from the extraordinary heroism shown by the Red forces. An army welded together in the fire of war and civil war could be victorious in battle against well-knit formations composed of officers, non-commissioned officers and men of the old regular Tsarist army only if its leaders contrived to exploit the heroism of revolutionary warriors in combination with tactical superiority at the decisive strategic centres of gravity.

No retrospective conclusions with regard to the employment of modern mass armies can be drawn from the engagements of the Russian Civil War. This may easily be seen from a comparison of the armies of 150,000 men and their inferior technical equipment with the man-power, running into millions, that provided the armies of the World War. In January 1918, for example, the Entente had 1,480,000 infantry, 74,000 cavalry, 8,900 light guns and 6,800 heavy guns on the western front against the 1,232,000 infantry, 24,000 cavalry, 8,800 field-guns and 5,500 heavy guns of the Germans.

The immense distances covered by the Whites were a special feature of the Russian Civil War. All the largest formations of White Guards were raised on the extreme edges of Russia, where Krasnov, Kolchak and Denikin began their attempted advances on Moscow. The length of their routes of march in the eastern and south-eastern theatres of war varied between 960 kilometres (Taganrog-Moscow) and 2,680 kilometres (Omsk-Moscow). On the European parts of the eastern and south-eastern theatres of war every stretch of railway had to serve 150-250 kilometres of the strategical front. The fronts were therefore excessively long, but in reality practically all operations were concentrated on points of strategic importance and more especially on railway-lines. Consequently advances and retreats of several hundred kilometres in length were not abnormal.

This concentration of operations on the railway-lines bestowed overwhelming importance on the armoured trains. A successful raid by one of these trains might result in the conquest of entire districts. Therein also lies the explanation of the ominous effect that the rebellion of the Czechoslovak Legion exercised on the whole development of the Civil War. But in the course of the years the importance of the railways was offset to some extent by the increased organizational capacity of both sides, whereupon the fronts assumed a more general nature.

Much of the hardest fighting took place in the Volga area, the possession of which was so strenuously contested by both sides. This is easily comprehensible in view of the fact that fifteen railway-lines approach the stream from the west, so that an enemy advancing from the east was able to make use of them as soon as he gained control of the river.

In a civil war the front is everywhere. The man-power reserves of both sides are distributed over the whole country. It must therefore be the endeavour of both belligerents to make active use of the reserves immediately behind the enemy’s front line and in the centres of government.

The part of these reserves which includes the lower middle classes of the towns and the peasants is bound to vacillate and develop its own activities in accordance with transient feelings; this is the soil on which guerilla warfare thrives. But other sections of the population immediately behind the front and along the lines of communication will comprise the enemy’s loyalist and most resolute adherents, for which reason espionage and counter-espionage assumed extraordinarily large dimensions in the Russian Civil War.

The activities of the White agents were mainly confined to military espionage in the narrow sense of the word and to acts of sabotage; only in exceptional cases did they undertake the organization of counter-revolutionary revolts. The latter type of work was, however, one of the most important tasks of the Red agents, who endeavoured to crown and complete the attacks of the regular Red forces by revolts of workers and peasants in the rear of the Whites.

The direction of Red espionage and counter-espionage rested entirely in the hands of the Cheka or ‘Extraordinary Commission for the Suppression of CounterRevolution.’ This body, which was the forerunner of the G.P.U., proved to be the all-seeing eye of the dictatorship of the proletariat during the years of the Civil War.

The Kronstadt Mutiny

Military intervention was not the hardest blow which the capitalist Powers dealt to the Socialist Revolution. The latter was hit far more severely by the blockade, which was complete enough to stifle all foreign trade, as may be seen by the following figures of imports and exports in millions of pouds:’

1 The poud is a Russian measure.

1913 — 1917 — 1918— — 1919 — 1920

Imports 936.6 178.0 11.5 0.5 5.2

Exports 1472.1 56.6 1.8 0.0001 0.7

In this connexion we must note that Tsarist Russia imported from abroad 58 per cent of its industrial machinery and plant and 45 per cent of its agricultural machinery.

3,762 railway bridges, 3,597 road bridges, more than 1,700 kilometres of railway-line, and over 90,000 kilmetres of telegraph wires were destroyed in the course of the Civil War. Moreover, the territory in possession of the Soviets was cut off for several years from the Caucasus oil deposits as well as from the most important industrial and agricultural centres for long periods. The consequences of this wholesale destruction hit the Red Army and the Soviet Republic in two directions-on its technical-economic side and on its social-political side.

As Trotsky most aptly remarked, the Bolshevists were compelled to” plunder all Russia” in order to satisfy the army’s most elementary needs. Trotsky certainly did not exaggerate, for in 1920 the army consumed 25 per cent of the entire wheat production, 50 per cent of the other grain products, 60 per cent of the fish and meat supplies, and 90 per cent of all the men’s boot and shoe wares. Moreover, the clothing supplied to the army was the barest minimum, while the deficiency in equipment was even greater. The combined effects of the blockade and of the separation of the Soviets from the important centres of production were seen in the fact that the war commissariat was unable to provide arms for more than 10 per cent of the men mobilized.

The Bolshevists were forced to commandeer all the peasants’ surplus grain in order to ensure the supplies needed to feed the army and the industrial proletariat. The so-called ‘requisition squads’ and the system of forced quotas which extracted the peasants’ last grain stores from their hiding-places and throttled all petty commerce were frequent causes of the peasantry’s vacillation to the side of the Whites.

But during the Civil War the peasants’ only choice lay between the communist requisition squads and the old landed proprietors, who wanted to deprive them of their land as well as their surplus stores. It was a hard choice, but in the end they decided that the communists were the lesser evil.

After the defeat of the Whites the peasants found themselves faced with another pair of alternatives. They could choose between the communist requisition squads and their own ‘independent economic system.’ In this case the choice was easy, and their opposition to the communists began to stiffen.

The policy of compulsory requisitioning of all peasants’ surplus products by agents of the dictatorship of the proletariat was a war measure which conflicted with all the theoretical conceptions held by the greatest of socialists. “War and destruction forced ‘war communism’ upon us,” wrote Lenin in his pamphlet on the natural produce tax in 1921. “This policy was not and never could be in accordance with the economic mission of the proletariat. It was merely a provisional measure. The correct policy of a proletariat which has achieved a dictatorship in a land of small middle classes is one that induces the peasant to exchange his produce for the products of industry which he needs. This is the food policy which harmonizes with the mission of the proletariat, and the only one capable of consolidating the basis of socialism and securing a complete socialist victory.”

When the Civil War came to an end in the autumn of 1920, the Bolshevists failed to realize the right way to effect a speedy abolition of the methods of ‘war communism,’ investigate their relations with the peasantry, and remould them on socialistic principles. Moreover, a consequence of the Civil War and of the absolute power placed in the hands of the communists by the necessities of warfare was manifested in the bureaucratic excrescences that flaunted themselves in all spheres of society-in the Soviets, trade unions, economic administration and throughout the machinery of government.

This bureaucratism found an extraordinarily fruitful soil in the backward state of the Russian people. Bureaucracy, as Lenin ascertained, developed particularly luxurious growths by reason of the methods used by ‘war communism.’

“We could not reorganize our industries when we were blockaded and besieged on all sides,” he wrote. “We dared not call a halt to ‘war communism’; in our despair we dared not shrink from extreme measures. But the measures which are an essential condition of victory in a blockaded land and a besieged fortress revealed their negative side in the spring of 1921, when the last White Guard forces had been driven off the soil of the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics. In a besieged fortress any and every exchange of goods must be stopped. Such a state of affairs may be endured for three years if the masses are particularly heroic, but meanwhile the impoverishment of the petty producers will increase. Bureaucratism has now revealed itslf as a legacy of the state of siege and a superstructure built on the bodies of the broken, crushed petty producers.”

In these words Lenin defined the facts of the retention of the policy of ‘war communism,’ which caused the Kronstadt Mutiny in March 1921.

The social-political essence of the four years’ Civil War shaped it as a struggle between the working class and the bourgeoisie for power over the masses of lower middle class individuals and, above all, over the peasantry. The fact that the bourgeoisie relied on the assistance of military formations sent by foreign imperialist powers gave this class war the characteristics of a national war of independence. The entire mass of the industrial proletariat was actively on the side of the Bolshevists during this civil war, while the rest of the proletarian and semi-proletarian classes gave some measure of support to the dictatorship of the proletariat, although with considerable vacillations.

The industrial proletariat also vacillated during the Kronstadt Mutiny. Its sympathies inclined to the cause of the men of Kronstadt, whom it supported openly by means of mass strikes in Petrograd and other large towns. As the bonds between the dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry had been severed, the Bolshevists now found themselves isolated for the first time since their victory in October 1917. But the machinery of state was shown to be firmly in their hands, while the ties between the peasant army and the village populations were loosened by years of civil war and the continual transference of the Red forces from one theatre of war to another. The army proved itself a reliable instrument in the hands of the Bolshevistleaders when they were forced to quell the Kronstadt Mutiny.

The note of this mutiny was sounded by mass strikes of the Petrograd workers. The Russian industrial workers had never quite lost their contact with the villages; when the pick of these workers were fighting on all fronts during the Civil War, their places in the factories were taken by a continual stream of labour pouring in from the villages; consequently the demands of the striking workmen brought a number of peasant problems into the foreground with them. On February 27, 1921, the Petrograd Strike Committee issued the following proclamation:

“The whole policy of the government must undergo a thorough change, and first and foremost the workers and peasants must have their freedom. They do not want to follow Bolshevist leaders; they want to decide their own lot for themselves. You must therefore put forward the following demands urgently and in an organized way:

“The release of all socialist and non-party workers who have been arrested.

“The abolition of the state of siege.

“Freedom of speech, the press, and meeting for all working classes.

“Free voting in new elections for the factory committees, trade unions and Soviets.”

The wage problem was as acute a question as the ugly mood of the workers. The average workman’s real wage was barely a third of his pre-War wage. In 1913 a factory worker generally earned something like 22 gold roubles a month, but his total monthly income in 1918 (wages plus food ration) had only the purchasing value of 8.99 pre-War roubles. In 1920 this purchasing value had sunk to 7.12 roubles, and in the spring of 1921 it was only 6.95 roubles, i.e. only 31.6 per cent of the pre-War wage.

The mutiny at Kronstadt broke out on March 3, 1921, at the time when a wave of strikes spread from Petrograd over the whole of Russia.

The sailors manning the fleet at Kronstadt were mainly recruited from lads of the Ukrainian peasantry. In its social-political aspect the Kronstadt Mutiny was therefore a peasant revolt, supported by part of the urban proletariat. In the course of the disturbances the peasants ejected the Bolshevist Soviets whenever they could institute mass action, organize military formations and obtain possession of arms.

The proclamations issued by the Kronstadt sailors contained many political and economic demands which were brought forward on behalf of the industrial proletariat in precisely the same way that the demands of the peasantry were incorporated in the strike manifestoes of the Petrograd workers. From this we may note that the workers exercised a strong influence on the mutineers. A large number of Kronstadt communists and practically the entire population of the islandcomposed mainly of fishermen and metal workerstook part in the rising. From a resolution passed by the 1st and 2nd brigades of battleship crews we may note the following sections:

(8) Abolition of the requisition squads.

(9) Equal rations for all workers except those engaged in unhealthy occupations.

(11) Liberty for the peasants to cultivate all the land in their own fashion; permission to own privately all the live stock they can keep without the employment of hired labour.

(15) Permission to carry on home industries not involving employment of hired labour.

The 13th issue of the News Bulletin of the Provisional Revolutionary Committee of Sailors, Red Army Men and Workers of the Town of Kronstadt, published on March 15, 1921, also states:

“All the peasant workers have been declared exploiters and enemies of the people. The enterprising Communists have taken the work of destruction in hand and are beginning to establish Soviet economy in the form of agricultural estates that are to be the property of the State, which is the new landed proprietor. Communist agricultural economy has been introduced everywhere, and the Communists have taken the best land for this purpose and placed a heavier, harder burden on the backs of the poor peasants than the old landed proprietors did in their time.”

The same number of this bulletin contains a quotation from a speech made by a peasant at the 8th Congress of Soviets held in December 1920. “All is well, but.

the land belongs to us, but the bread from it is yours; the rivers belong to us, but the fish to you; the forests belong to us, but the wood from them to you.”

The political aims of the Kronstadt Mutiny may be ascertained from a leading article in the fifth issue of the same bulletin, which states:

“Here in Kronstadt was laid the corner-stone of the Third Revolution, which freed the working masses from their last remaining fetters and opened the way to the construction of a socialist state. The present revolution will allow the working masses freely to elect their own Soviets, which can then do their work without pressure from the Party and transform the bureaucratic trade unions into free organizations that will unite the workers, peasants and intelligentsia.”

The 10th Bolshevist Party Congress was in session at Moscow when the news of the Kronstadt Mutiny came through. At first the assembled delegates thought Kronstadt was going to provide another ‘Czechoslovak Insurrection’ and a beacon to light another civil war and provoke further intervention. The spectre of a new civil war cast its shadow over the whole Soviet Republic, for the exiled leaders of the Menshevist, Social Revolutionary, Cadet and Monarchist parties all sent their good wishes to the Kronstadt mutineers.

An army was despatched to Kronstadt under Tuchachevsky’s command. Several hundred delegates volunteered for service as officers and commissars in the contingents that were to liquidate the mutiny. Then, while the mutineers sent telegram after telegram to “Lenin, the incorruptible,” Tuchachevsky’s forces advanced from Krasnaya Gorka across the treacherous ice of the Gulf of Finland which the spring gales were breaking up. On the night of March 16 they overpowered the sleeping Kronstadt, which had deemed any form of attack from the sea an impossibility. More executions followed, the rebels were shot as mutineers and counter-revolutionaries, but the economic points of their programme were embodied in the resolutions of the 10th Party Day, which advocated the replacement of the quota system by a produce tax, and were realized later in the New Economic Policy (Nep). The political demands of themen of Kronstadt (which, despite their vagueness, aimed at the restoration of Soviet democracy) attained, however, only to a partial and incomplete realization. Lenin, indeed, began the struggle against bureaucracy, but owing to his illness and premature death this ‘legacy’ of Tsarist backwardness and the Civil War spread like a plague.

The swift liquidation of the Kronstadt Mutiny showed the Bolshevist Party wherein the weakness of any mass movement directed against the party in power lay.

The Bolshevist Party had acquired a monopoly of authority; it was the only organized force which represented the Soviet Russian proletariat. That was its strength, but therein also lay the seeds of its decay.

On the occasion of the celebration of his fiftieth birthday on April 23, 1920, Lenin took the opportunity to address a meeting of the active members of the Moscow branch of the Party in the following terms:

“Even today our Party might, under certain circumstances, fall into a very dangerous position. It might fall into the position of a man who has grown presumptuous. Everyone knows that the decline and fall of political parties is often preceded by some circumstance which gives these parties the chance to grow presumptuous. Permit me to conclude with the hope that under no circumstances will our party ever become a presumptuous party.”

proletariat rather than the vacillating bourgeois democracy. But the hard struggle for self-preservation and the consolidation and amplification of the October Revolution, which lasted nearly four years, did not begin until after the easily won victory of that October of 1917.

proletariat rather than the vacillating bourgeois democracy. But the hard struggle for self-preservation and the consolidation and amplification of the October Revolution, which lasted nearly four years, did not begin until after the easily won victory of that October of 1917.