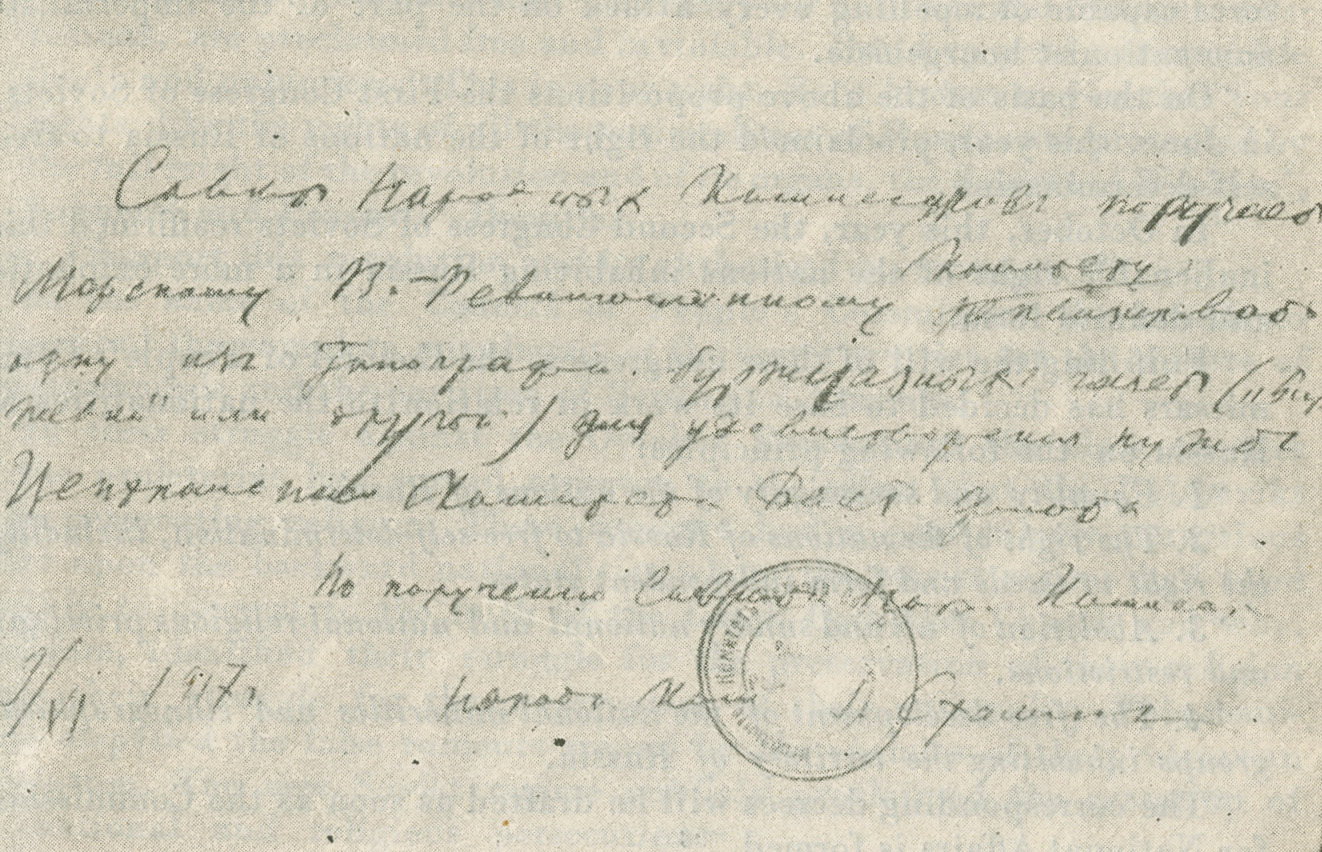

In all the Commissariats the struggle against sabotage accelerated the break-up of the old state machine and the building of a new state apparatus. The introduction of state control of the banks as a preliminary to their nationalisation encountered the hostility of the bank officials, so much so, that before the sum of 10,000,000 rubles could be drawn from the State Bank to the order of the Council of People’s Commissars, the Bank Director Shipov had to be arrested and the bank officials threatened with the calling of the Red Guards. This sabotage hastened the nationalisation of the banks. At a meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee held on November 8, a resolution was adopted on the report made by Comrade Menzhinsky ordering “the Council of People’s Commissars to take the most vigorous measures for the immediate liquidation of the sabotage of the counter-revolutionaries in the State Bank.”[1]

A similar situation prevailed in the People’s Commissariat of Post and Telegraph. The sabotage of the officials of the former Ministry of Post and Telegraph was directed by the Central Committee of the Post and Telegraph Employees’ Union, which was controlled by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. On its initiative a “business committee” of three, consisting of monarchist officials, was appointed to take charge of the Ministry. To break this sabotage naval telegraph operators were called in from Kronstadt. After taking over the Telegraph Office the sailors, in the middle of November, drove the saboteurs out of the Ministry.

At the Ministry of Labour the Mensheviks were the ringleaders of the sabotage. The Marble Palace, which this Ministry occupied, was deserted, all the desks were locked and not a single official was to be found. In the corridors young princes, the sons of the Grand Duke Constantine, hovered like shadows. Under Skobelev and Gvozdev they had remained masters of the palace. Several days after the October Revolution they were ordered to leave, as they were stealing the palace treasures, and encouraged by their example, the officials stole the cash and carried away the account books. But in spite of the sabotage, the new Commissariat of Labour began to introduce social insurance and workers’ control of industry. Workers from the Petrograd factories were called in to augment the staff.

One of the most important tasks that confronted the Soviet Government was to establish revolutionary order in the capital. The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs set up a committee for the maintenance of public order headed by K. E. Voroshilov. The counter-revolutionaries tried to organise hooligan and anarchist rioting in the city. Members of Purishkevich’s organisation scattered leaflets in the city giving the addresses of vodka stores, and suspicious characters, disguised as workers, flitted through the streets organising the anarchist elements for the purpose of raiding the wine shops. Under the slogan of: “Let us drink up the last of the Romanov stocks,” the counter-revolutionaries tried to cause disorder and anarchy in revolutionary Petrograd. Long queues lined up outside the raided vodka stores. In the Winter Palace and the Hermitage there were sealed cellars containing costly wines. The palace officials deliberately told the guards how to reach these cellars with the object of getting them intoxicated. Thus encouraged, the sentries removed the bricks from the walls with their bayonets and got to the wine. The guard was changed again and again, but without avail. The lure of the wine was too strong. Outside the palace there was a huge line of people, stretching to the Liteiny Bridge and along Millionnaya Street to the Field of Mars, waiting to get into the wine cellars. At about this time over twenty vodka stores had been wrecked in the city. The drunken riots that took place in different parts of the city became a serious menace to revolutionary order in the capital. In some districts these riots developed into anti-Soviet demonstrations. Order was restored only with the aid of detachments of Communists, revolutionary sailors and Red Guards.

An important part in the work of maintaining revolutionary order was taken by the workers’ militia. Under the Provisional Government the City Militia had retained many of the features of the old tsarist police force. This extremely important part of the old state machine was broken up during the very first days of the October Revolution. By a decree issued on October 28, all local Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies were instructed to form a workers’ militia in their respective districts and to exercise complete control over it.

Neither the Mensheviks nor their inspirers displayed any originality in believing that their sabotage would undermine the position of the Bolsheviks and send them “hurtling over the precipice.” During the insurrection of the workers of Paris in 1871, Thiers, the leader of the counter-revolution, resorted to the same methods. When the Communards went to the Municipal offices to carry out their functions they found the premises deserted. When Arthur Arnoult arrived at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs he found nobody there but a caretaker and a floor polisher.

The schemes of the Russian saboteurs were foiled. They imagined that the proletarian revolution would treat the bourgeois state in the same way as all previous revolutions had done, but they were mistaken. The Bolshevik attitude towards the state machine was based on the granite foundation of the theory of Marx and Lenin, which had been tested by the experience of the Paris Commune and by the Russian revolution of 1905. The experience of the revolution of February 1917 still further confirmed the soundness of this theory. Lenin wrote:

“Take what happened in Russia during the six months after February 27, 1917. Government jobs became the goal of the Constitutional Democrats, Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries. They did not think of introducing serious, radical reforms. They kept on postponing these ‘until the Constituent Assembly met,’ and bit by bit postponing the meeting of the Constituent Assembly to the end of the war! But they did not postpone the sharing of the spoils, obtaining jobs as ministers, vice-ministers, governors-general, and so on, and so forth, and did not wait until the Constituent Assembly met. In fact, the game of combinations played in connection with the formation of the government was nothing but an expression of the sharing and re-sharing of the “spoils” that was going on from top to bottom, all over the country, in all the central and local administrations.”[2]

Shortly before the proletarian revolution, while living underground after the July days, Lenin enunciated the Bolshevik views on the state in his book The State and Revolution. Lenin foresaw that in the impending revolutionary battles the proletariat, which was about to storm the fortress of the capitalist system, would need a precise theory to guide it. It is exactly for this reason that Lenin availed himself of the opportunity afforded by his enforced retirement from public political activities to write this book. The book was not yet finished when the cold weather set in at the beginning of September and Lenin was obliged to move to quarters in Finland. On mounting the locomotive on which he crossed the border, he handed the workman who accompanied him a blue-covered exercise-book and exhorted him to guard it as the apple of his eye, adding that if he (Lenin) should be arrested, he was to deliver the book to Stalin. The locomotive safely crossed the border and Lenin’s first question on reaching the other side was whether the exercise-book was safe. On receiving the precious manuscript he carefully put it away.

This blue-covered exercise-book, bearing the inscription “Marxism on the State,” contained excerpts which Lenin had copied from the works on the state by Marx, Engels and others, the study of which he began in the reading-room of the Zürich Public Library in Switzerland.

The State and Revolution was finished in Finland in September 1917. In this brilliant work Lenin restores the ideas of Marx on the state which the opportunists, the Russian and other Mensheviks, had hushed up.

In the Communist Manifesto Marx showed that it was necessary for the proletariat to establish its rule and that it needed a state as a special instrument of violence to be used against the bourgeoisie. But he did not in that work indicate how the proletariat should deal with the bourgeois state machine. Marx and Engels were able to formulate this after generalising the experience of the revolution of 1848-1851.

Lenin quotes the following excerpt from Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

“. . . the parliamentary republic, in its struggle against the revolution, found itself compelled to strengthen, along with the repressive measures, the resources and the centralisation of governmental power. All the revolutions perfected this machine instead of smashing it.”[3]

To this Lenin makes the following comment:

“In this remarkable passage Marxism takes a tremendous step forward compared with the Communist Manifesto. In the latter the question of the state is treated in an extremely abstract manner, in the most general terms and expressions. In the above-quoted passage the question is treated in a concrete manner and the conclusion is most precise, definite, practical and palpable; all the revolutions which have occurred up to now have helped to perfect the state machine, whereas it must be smashed, broken.

“This conclusion is the main and fundamental thesis in the Marxian doctrine of the state.”[4]

He went on to stress the following:

“Break up this machine, smash it—this is what really serves the interests of ‘the people,’ the workers and the majority of the peasants; such is the ‘condition precedent’ of the free alliance of the poorest peasants with the proletariat; and without such an alliance democracy is unstable and Socialist reforms impossible.”[5]

In his The State and Revolution Lenin for the first time enunciated and substantiated the theory that the proletarian dictatorship must assume the form of a Soviet Republic.

Right up to the second Russian revolution in February 1917, the Marxists of all countries had regarded the parliamentary democratic republic as the most suitable political form of organisation of society during the period of transition from capitalism to Socialism. In the 1870’s Marx stated that a political organisation of the type of the Paris Commune was the most suitable form of the proletarian dictatorship. But he did not develop this idea any further in his works.

In his Criticism of the Draft Social-Democratic Program, 1891, Engels stated:

“. . . our Party and the working class can achieve dominance only under a political form such as the democratic republic. The latter is, in fact, the specific form for the proletarian dictatorship. . . .”[6]

Subsequently, this thesis became the guiding principle for all Marxists, including Lenin.

True, guided by the experience of the revolution of 1905, Lenin arrived at the conclusion that the Soviets were the embryo of revolutionary government in the period of the overthrow of tsarism. In 1915, he wrote:

“Soviets of Workers’ Deputies, and similar bodies, must be regarded as organs of insurrection, as organs of revolutionary government.”[7]

But neither in 1915 nor later—right up to the revolution of February 1917—had Lenin had any experience of “a Soviet Government organised on a nation-wide scale as the state form of the proletarian dictatorship. . . .” (Stalin.)[8] Studying the theories of Marxism, the experience of the Paris Commune, the 1905 Revolution, and particularly the first stage of the revolution of 1917, Lenin arrived at the conclusion that the Republic of Soviets was the state form of the proletarian dictatorship. He formulated this theory in his April Theses, but he expounded it in detail and substantiated it in the autumn of 1917 in his book The State and Revolution.

In this book he lays it down that the old state machine must be broken up and replaced, not by a democratic republic, but by Soviets of Workers’ Deputies. Stalin arrived at the same conclusion. In an article published in Pravda in March 1917, he called for the amalgamation of the Soviets all over the country and for the formation of a Central Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. Like Marx, Lenin and Stalin did not devise a new form of government; they studied "the way revolutions themselves ‘discover’ . . . it, the way the working-class movement itself approaches this task and begins, in practice, to carry it out.”[9]

Just prior to the October insurrection the great leader of the revolution wrote a pamphlet entitled Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power? in which, with amazing daring and lucidity, he indicated and provided solutions for the practical problems that would confront the victorious revolution. He attached exceptional importance to what he described as “one of the most serious, one of the most difficult problems that faces the victorious proletariat, namely, the attitude to adopt towards the state.”

“By the state apparatus,” he wrote, is “meant, first of all, the standing army, the police and the bureaucracy. . . . Marx taught us, from the experience of the Paris Commune, that the proletariat cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and set it in motion for its own purposes, but that the proletariat must destroy this machinery and replace it by a new one. . . . This new state machine was created by the Paris Commune, and of the same type of ‘state apparatus’ are the Russian Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies’.”[10]

Lenin taught the proletariat not only what to do with the bourgeois state machine, but also how to treat those institutions which do not fulfil repressive functions. Further on in the above-mentioned pamphlet he wrote:

“Besides the preponderantly ‘repressive’ machinery, the standing army, the police, and the bureaucracy, there is in the modern state a machinery that is closely connected with banks and syndicates which perform an enormous amount of work in the way of accounting and record-keeping, if one may so express it. This machinery cannot and must not be broken up. It must be forcibly freed from subjection to the capitalists; the latter must be lopped off, hacked, chopped away from it together with the threads which transmit their influence; it must be subjected to the proletarian Soviets; it must be enlarged, made extensive, more popular.”[11]

Lenin had in mind the banks, the post office, the telegraph and the consumers’ co-operative societies. But this machinery can be utilised only if the bourgeois state is smashed, only if the capitalists are “cut off, chopped away.” Moreover, he emphasised that the proletariat would encounter the resistance of the higher officials even in the non-repressing apparatus. Referring to these, he wrote:

“As for the higher grades of employees, of whom there are very few, but who incline towards the capitalists, we shall have to treat them like capitalists—’with severity.’ They, like the capitalists, will resist, and this resistance will have to be broken. . . .”[12]

The sabotage of the officials hindered the utilisation of some of the parts of the old and discarded state machine that could be used, but at the same time it accelerated the demolition of the old state machine and the creation of a new one. It was in the struggle against this sabotage that the new state administration which grew out of the Soviets was built up.

The Soviet Government that was formed by the decision of the Second Congress of Soviets set to work immediately, but the new Commissariats had neither staffs nor premises. The People’s Commissars took up their quarters in the Smolny, in the rooms of which small tables were placed with tablets attached bearing the inscription: “People’s Commissariat . . .” stating which Commissariat it was. The Bolsheviks who were appointed as Commissars, weary though they were from sleepless nights during the insurrection, took up their duties at once.

Thus, on October 30, Comrade Menzhinsky was appointed People’s Commissar of Finance. With the intention of proceeding forthwith to carry out the government’s order he, with the help of another comrade, dragged a large couch into the room occupied by the Secretary of the Council of People’s Commissars and attached a slip to the wall above it with the inscription: “Commissariat of Finance.” Then, having had no sleep for several nights, he lay on the couch and fell fast asleep. Lenin happened to pass by and seeing the slumbering Commissar laughed and said: “It’s a good thing the Commissars begin by recuperating their strength.”[13]

During these first days after the October Revolution the People’s Commissars rarely visited the old Ministries and the Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and Constitutional Democrats took this as a sign of the Bolsheviks’ weakness.

“Nobody seriously believed in their triumph,” wrote Demyanov, “and the Bolsheviks themselves were not sure that they had captured power for good. This was indicated by the fact, among others, that at first they paid hardly any attention to that part of the administration which dealt with the state functions of the Ministry.”[14]

Like the Mensheviks, the old bureaucrats could not conceive of a state administration without Ministries. The old administration continued to function by inertia. The officials arrived at their offices every morning as usual, and the Ministries continued, as usual, to issue innumerable circulars to all parts of the country. In those cases where the People’s Commissars attempted to take over the affairs of their respective Ministries they encountered the passive resistance of the officials. It was enough for the Commissar to appear in the building for all the rooms to become deserted. Only the technical personnel and those officials who sympathised remained in their places.

In the first days of the existence of the Soviet Government the People’s Commissars tried to make use of the rump of the old state administration. It was, indeed, only a rump, for it no longer exercised any power. Nevertheless, it had to be taken over; it was necessary to pick up its connections and to collect a loyal staff. In this short period after the October Revolution some of the People’s Commissars signed decrees as “Commissars of the Ministry.” Thus, A. V. Lunacharsky, the Commissar of Education, stated in the first declaration he issued on the principles on which public education was to be organised:

“For the time being, current affairs must be carried on in the ordinary way, through the Ministry of Public Education.”[15]

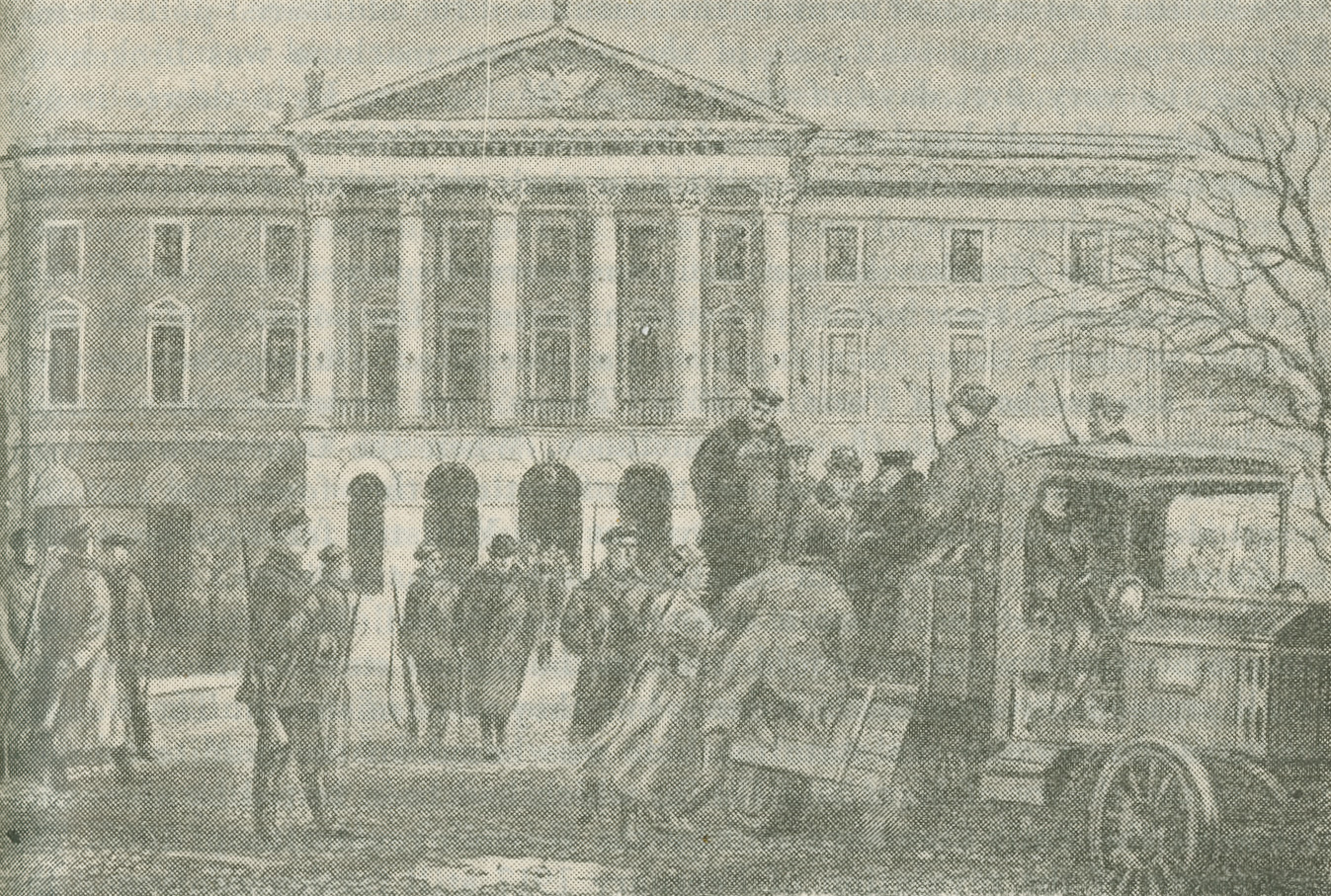

The growing dimensions of the sabotage proved, however, that the old state machine had to be broken up as much as possible. The result was that very little of it remained that could be utilised. This sabotage assumed the most diverse forms, from open refusal to work to naive attempts to confuse the representatives of the Soviets by formal routine. Thus, when the members of the Collegium of the Commissariat of Post and Telegraph arrived at the Ministry which had administered this department, the officials demanded proof that the Collegium was really authorised to direct the Ministry. The members of the Collegium presented a document to that effect, signed by Lenin. The officials scrutinised the document, held a whispered consultation and then stated that the document was invalid as it had no file number and bore no seal. Lenin was informed of this. He examined the document, burst out laughing and said:

“They are quite right. An official document like this should have had a seal and a file number. But you are already sitting tight in the Ministry. This proves that a revolution can be made without a file number.”[16]

The counter-revolutionaries banked on the Bolsheviks being unable to find the forces with which to man the new state administration, but in this, too, they were mistaken. On October 29 the Military Revolutionary Committee issued the following circular to all the district Revolutionary Committees:

“Inform all factory committees, district trade union committees, sick insurance committees, Party committees, and other proletarian organisations that they are immediately to choose people of both sexes who are willing to work in the revolutionary organisations as bookkeepers, typists, bank messengers, for permanent or temporary employment.”[17]

Somewhat later, on November 17, when the sabotage of the government officials was at its height, a similar order was issued by the Petrograd Soviet. It read as follows:

“1. . . The pernicious bourgeois prejudice that only bourgeois officials can administer the state must be utterly discarded forthwith.

“2. The District and City Soviets must without delay divide into departments, each of which must take a most active part in the work of one or other branch of state administration.

“3. The most class-conscious comrades with organising ability must be chosen from the factories and the regiments; the forces thus obtained are to be sent to assist the various People’s Commissariats.

“Every class-conscious worker and soldier must understand that only by displaying self-reliance, energy and enthusiasm can the working people consolidate the victory of the social revolution which has begun. Let every group of workers and soldiers display the organising talent that lies dormant among the people and was hitherto repressed by the yoke of capital and by want.”[18]

At first the People’s Commissariats enlisted small groups of workers with whose aid they set to work to break up the old administration and to build the new. These people who came to work in the Soviet offices were new in the literal sense of the word. They were people of the new class and had their roots deep among the masses. Lenin said on more than one occasion: “. . . The proletarian revolution is strong precisely because its sources are so deep.”[19]

Appointments to leading positions in the new state administration were made by the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party, by the Military Revolutionary Committee, and personally by Lenin, Stalin and Sverdlov. The most active members of the District Soviets, District Committees of the Bolshevik Party and of the trade unions, the factory committees, the Red Guard and other organisations were chosen for these positions.

One of the most important Commissariats to be set up was the People’s Commissariat for Nationalities. In view of the numerous nationalities inhabiting the country, this state department was destined to play an exceptionally important role. Right from the very inception of the Soviet regime the question as to whose lead the oppressed nationalities would follow—that of their “own” national bourgeoisie, or that of the working class—was one on which the very existence and further progress of the revolution depended. For this reason the Bolshevik Party placed Stalin at the head of the People’s Commissariat for Nationalities. Lenin’s best disciple, leader and guide of the Bolshevik organisations, Stalin, also enjoyed renown as a Bolshevik theoretician on the national question.

Like the other Commissariats, the People’s Commissariat for Nationalities started to function in the Smolny. In a room already occupied by a number of departments, a desk was placed and on the wall above it there was a tablet with the inscription: “People’s Commissariat for Nationalities.” Up to the end of 1917, the staff of this People’s Commissariat consisted of three persons. The “Director of the Chancellery” of this Commissariat was a Bolshevik named Felix Senyuta, who gave up his cobbler’s last for a statesman’s portfolio.

Stalin soon developed enormous activity in rallying the masses of the oppressed nationalities in the East and the West around revolutionary Russia. In these first days of the existence of the Soviet regime the People’s Commissar for Nationalities laid down the principles which guided the policy of the Soviet Government in the national question. On November 2, the “Declaration of Rights of the Nations of Russia” was published over the signature of Lenin and Stalin. This declaration had been drawn up by Stalin. In plain, forceful language, it expressed the hopes and aspirations of hundreds of millions of the oppressed toiling masses all over the world. It read as follows:

“The October Revolution of the workers and peasants has commenced under the common banner of emancipation.

“The peasants have been emancipated from the power of the landlords, for landlordism no longer exists; it has been abolished. The soldiers and sailors have been emancipated from the power of the autocratic generals, for henceforth generals will be elected and be subject to dismissal. The workers have been emancipated from the caprice and tyranny of the capitalists, for henceforth the factories and works will be under the control of the workers. All that is vital and virile is being emancipated from its hated fetters.

“There remain only the nations in Russia which have suffered, and are still suffering, oppression and tyranny, whose emancipation should commence immediately and whose liberation should be brought about resolutely and for ever.

“In the epoch of tsarism the nations in Russia were systematically incited against one another. The results of this policy are common knowledge: massacres and pogroms on the one hand, and the slavery of the nations on the other.

“This disgraceful policy of incitement has been abolished, never to be revived. Henceforth, its place will be taken by a policy of voluntary and sincere alliance of the nations in Russia.

“In the period of imperialism, after the February Revolution, when power passed to the bourgeoisie represented by the Constitutional Democratic Party, the naked policy of incitement gave way to the craven policy of sowing mutual distrust among the nations in Russia, a policy of pinpricks and provocation covered up by glib talk about “freedom” and “equality” of nations. The results of this policy are common knowledge. Growth of national enmity and mutual distrust.

“This despicable policy of falsehood and distrust, of pinpricks and provocation must be brought to an end. Henceforth, it must be replaced by an open and honest policy that will lead to complete mutual confidence among the nations of Russia. . . .

“Only as a result of such an alliance can the workers and peasants of the different nationalities in Russia be merged in a single revolutionary force capable of repelling every attack on the part of the imperialist-annexationist bourgeoisie.

“On the basis of the above propositions the First Congress of Soviets, in June, this year, proclaimed the right of the nations of Russia to free self-determination.

“In October, this year, the Second Congress of Soviets reaffirmed this inalienable right of the nations inhabiting Russia in a more emphatic and definite form.

“Fulfilling the will of these congresses, the Council of People’s Commissars has decided to base its work in relation to the nationalities of Russia on the following principles:

“1. Equality and sovereignty of the nations of Russia.

“2. The right of the nations of Russia to free self-determination, including the right to secede and form independent states.

“3. Abolition of all and sundry national and national-religious privileges and restrictions.

“4. The free development of the national minorities and ethnographical groups inhabiting the territory of Russia.

“The corresponding decrees will be drafted as soon as the Commission for National Affairs is formed.”[20]

These four points summed up the program of action in the national question of the first proletarian state in history.

On November 22, a manifesto addressed “To All the Toiling Mohammedans in Russia and in the East,” written by Stalin, was issued in the name of the Council of People’s Commissars and signed by Lenin and Stalin. The manifesto read as follows:

“Comrades! Brothers!

“Great events are occurring in Russia. The bloody war which was launched for the purpose of dividing up foreign countries is drawing to a close. The rule of the pirates who have enslaved the peoples of the world is tottering. Under the hammer blows of the Russian revolution, the ancient edifice of bondage and slavery is being shattered. The world of tyranny and oppression is living its last days. A new world is being born, a world of the working people and of those who are being emancipated. At the head of this revolution marches the workers’ and peasants’ government of Russia, the Council of People’s Commissars. . . .

“The reign of capitalist plunder and violence is crumbling. The soil is burning under the feet of the imperialist robbers.

“In the midst of these great events we address ourselves to you, toiling and dispossessed Mohammedans of Russia and the East.

“Mohammedans of Russia, Tatars of the Volga and the Crimea, Kirghiz and Sarts of Siberia and Turkestan, Turks and Tatars of Transcaucasia, Chechens and Gortsi of the Caucasus, all those whose mosques and prayer houses were destroyed and whose religion and customs were trampled upon by the Russian tsars and tyrants!

“Henceforth, your faith and customs, your national and cultural institutions, are proclaimed free and inviolable. Build up your national life freely and unhindered. This is your right. Be it known to you that your rights, like the rights of all the nationalities of Russia, are protected by the full might of the revolution and of its organs, the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies.

“Support this revolution and its authorised government.”[21]

In the name of the Council of People’s Commissars the manifesto announced the complete annulment of the secret treaties for the seizure of Constantinople and the partition of Persia and Armenia.

In their struggle against the October Revolution, the class enemies of the proletariat had spread rumours to the effect that the Bolsheviks were persecuting religion. These rumours had a particularly pernicious effect upon the backward nationalities whom the tsarist regime had tried forcibly to convert to the faith of the Greek Orthodox Church and who, therefore, identified their struggle for the preservation of their religion with their struggle for the preservation of their nationality. This manifesto dispelled the false rumours spread by the enemies of the proletarian revolution. The new Soviet regime publicly proclaimed the cessation of all national and religious persecution.

The manifesto to Mohammedans vividly revealed what a wide gulf lay between the imperialist and the Soviet national policies. Tsarist Russia was the bugbear of her weaker eastern neighbours. The Mohammedan peoples of Turkey, Persia and other Oriental countries lived in constant dread of sharing the fate of Turkestan and Transcaucasia, which tsarism had converted into its colonies. But a new, revolutionary regime was established, which most emphatically declared that it had put an end to the imperialist policy of tsarist Russia once and for all. The Soviets converted this declaration into action. When the Finnish Diet voted in favour of secession from Russia, the Council of People’s Commissars, on December 18, 1917, issued a decree recognising the independence of the Finnish Republic. Later, on December 22, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, after hearing a statement by Stalin, adopted “The Revolutionary Government’s Declaration on the Independence of Finland.” The policy long pursued by tsarism had caused the masses of the working people of Finland to distrust everything Russian. By ratifying Finland’s secession the Soviet Government proved that it had no intention of oppressing other nations in the slightest degree. The Finnish working class became convinced that alliance with Soviet Russia would not lead to national subjugation.

The Soviet Government’s decision concerning Turkish Armenia was enthusiastically welcomed among the oppressed nations outside of Russia. In December 1917, Stalin, People’s Commissar for Nationalities, issued an appeal in the course of which he said:

“Turkish Armenia is the only country, I believe, that Russia occupied by right of war. This is the bit of ‘Paradise’ which for many years has been (and still is) the object of the voracious diplomatic appetites of the West and of the bloody exercises in administration of the East. Armenian pogroms and massacres, on the one hand, and the pharisaical ‘intercessions’ of the diplomats of all countries as a screen for fresh massacres, on the other hand, and a blood-bedrenched, deceived and enslaved Armenia. . . . It is becoming clear that the path of liberation for the oppressed nations lies through the workers’ revolution that was started in Russia in October. It is now clear to all that the fate of the nations of Russia, and particularly the fate of the Armenian nation is closely bound up with the fate of the October Revolution. The October Revolution has broken the chains of national oppression. It has torn up the tsarist secret treaties, which tied the nations hand and foot. It, and it alone, can carry the cause of emancipation of the nations of Russia to its very end.”[22]

This appeal of Stalin’s was soon followed by the decree of the Council of People’s Commissars of December 29, 1917 “On Turkish Armenia,” which declared that:

“. . . the Workers’ and Peasants’ Government of Russia supports the right of the Armenians in Turkish Armenia, which is occupied by Russia, to free self-determination. . . .”[23]

Of extreme world-wide historical significance was the publication by the Soviet Government of the secret predatory treaties concluded by the tsarist government and the Provisional Government. The work of the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, like that of other People’s Commissariats, was being performed by workers, sailors and Red Guards, now the real rulers of the country. The first nucleus of the staff of the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs consisted of workers from the Siemens-Schuckert Works, and it was thanks to them that the archives of the former Ministry for Foreign Affairs were saved. A sailor named Markin undertook the work of publishing the secret diplomatic documents. Unfamiliar with foreign languages he managed to find translators and succeeded in publishing the Digest of Secret Documents in six issues. This work was performed very expeditiously, the whole series being published in the course of only six weeks. Markin personally supervised the process of printing. These documents exposed the predatory policy of the tsarist government and the whole system of secret diplomacy. The Diplomatic Corps and the foreign press correspondents in Petrograd snatched up every issue of the Digest as soon as it came out. The strike committee of the officials of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs bought up all the copies it could and destroyed them.

The archives of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs contained a large quantity of correspondence written in secret cipher. The officials of the Ministry, and Neratov, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, had taken the precaution to take with them the key to the cipher when they left the Ministry. Markin together with several Red Guards sat up whole nights working on these documents and succeeded in deciphering most of them. Thus, new cipher experts were trained. In his preface to the Digest of Secret Documents Markin wrote:

“Let the working people all over the world know how the diplomats in their closets traded in their lives . . . concluded shameful treaties behind their backs.

“Let all and sundry know how by a stroke of the pen the imperialists annexed whole regions. They irrigated the fields with human blood. Every revealed document is a weapon of the sharpest kind against the bourgeoisie.”[24]

The publication of the secret treaties was the first step in the international policy of the Soviet Government, which emphatically rejected the predatory policy of the capitalist and landlord government.

The men in charge of the organs of the proletarian dictatorship had trained themselves for the work of statesmanship in the long years of Party activity underground, in exile and as political émigrés abroad. The very first days of the October Revolution revealed what vast talent, what a vast number of organisers, not only of Party work, but also of state administration, lay dormant in the ranks of the vanguard of the Russian proletariat. The metal-workers M. I. Kalinin, who took charge of the capital’s municipal affairs, and G. I. Petrovsky, who became People’s Commissar for Internal Affairs, and professional revolutionaries like Sverdlov and Menzhinsky—such were the typical organisers and statesmen who had been trained by the Bolshevik Party. The following description of Sverdlov by Lenin summed up the characteristics of all the leaders of the new state:

“. . . the profound and constant feature of this revolution, and the condition which ensured its victory was, and still is, the organisation of the proletarian masses, the organisation of the working people. . . . It was this feature of the proletarian revolution that brought to the front in the course of the struggle leaders who above all else were the embodiment of this specific factor hitherto lacking in revolution—the organisation of the masses. . . . Sverdlov’s wonderful organising talent was cultivated in the course of a long struggle. . . . This leader of the proletarian revolution himself forged every one of his wonderful qualities as a great revolutionary, having experienced and passed through different periods under the most arduous conditions a revolutionary has to endure . . . traversing a long road of underground activity. This is the most characteristic experience of a man who, while constantly engaged in the fight, never became divorced from the masses, never left Russia, always operated in conjunction with the best of the workers and, in spite of the life of seclusion to which persecution condemned the revolutionary, succeeded in training himself to become not only a popular labour leader, not only a leader familiar mainly with practical work, but also an organiser of the advanced proletarians.”[25]

During the “Smolny period” the Commissariats dealt with the most diverse aspects of the life of the young republic—from making grants to peasants whose horses had been sequestered under the tsarist regime to nationalising the banks, organising the first food supply detachments and building up an intricate machine for regulating and managing the economy of the country.

Already in the manifesto of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets which announced the victorious insurrection of the workers and soldiers, Lenin had written that the Soviet Government would immediately introduce workers’ control of industry. On October 29 and 30, when the roar of the guns of Kerensky and Krasnov were heard at Gatchina and the cadets had risen in revolt in Petrograd, Lenin drafted the regulations governing workers’ control.

In this draft Lenin proposed that in all industrial, commercial, financial, agricultural, transport and other establishments employing hired workers or clerical staffs, or giving out work to be done at home, the workers should be placed in control of the production, purchase, sale and warehousing of goods and raw materials, and also of financial transactions. The workers in each establishment were to exercise this control through bodies which they were to elect and which were to enlist the co-operation of representatives of the office and technical staffs. Commercial secrets were to be abolished. The owners of the different enterprises were to be compelled to submit all their books and accounts for control. In his draft Lenin emphasised that the workers’ control bodies were to be organs of the Soviets, i.e., organs of the proletarian dictatorship.

On November 14, Lenin’s draft was examined and endorsed by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, and on November 15 it was endorsed by the Council of People’s Commissars. The introduction of workers’ control of industry was a most important Socialist measure. It placed an instrument in the hands of the proletarian state which enabled it to probe into the workings of every industrial and commercial establishment; it deprived the bourgeoisie of the opportunity of utilising its economic power for counter-revolutionary purposes, and it was an important step towards the nationalisation of industry.

At this time the Soviet Government also set to work to build up machinery for managing the economy of the country. On October 26 and 27, a group of members of the Central Council of Factory Committees discussed this question and drew up a scheme for the formation of a Supreme Council of National Economy. Several days later Lenin invited the group to his room in the Smolny and there, seated at a small round table, he examined their scheme, questioned them about every detail and devoted special attention to the proposed personnel of this new body. Lenin stressed the point that with the task ahead of socialising the means of production, the workers’ government needed an organ through the medium of which the working class could manage their industries.

On November 10 the question of forming an Economic Council was discussed at a conference of representatives of Petrograd workers’ organisations. At this conference an anarcho-syndicalist proposal was made to transfer the management of industry to the trade unions, but this was rejected. Guided by Lenin, the members of the Central Council of Factory Committees firmly pursued the line of establishing a state organ for the management and regulation of the national economy. A committee of members of the Central Council of Factory Committees was appointed to draw up the regulations that would govern the functions of a Supreme Council of National Economy. In its work the Committee had to contend against the defeatist proposals of Bukharin, who strongly opposed the complete break-up of the old state administration and insisted that the Supreme Council of National Economy should be constituted from the surviving organisations of the Kerensky government, such as the Special Fuel Department, the Economic Committee, etc., which, as was common knowledge, had served as centres of Kornilov counter-revolution in the economic sphere.

Proposals on the same lines were made by Larin, who urged that the Supreme Council of National Economy should contain a large number of capitalists and representatives of the so-called “public organisations.” Under this scheme the workers were to have only one-third of the seats on the Supreme Council of National Economy.

At the meeting of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee where these questions were discussed, these proposals were supported by the Menshevik Katel. Lenin opposed them in the following terms:

“. . . The Supreme Council of National Economy cannot be converted into a parliament. It must be a militant organ for combating the capitalists and landlords in the sphere of economics, just as the Council of People’s Commissars is such an organ in the field of politics.”[26]

On December 1, 1917, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee passed a decree, signed by Lenin, Stalin and Sverdlov, ordering the formation of a Supreme Council of National Economy.

One of the first Commissariats to start functioning was the People’s Commissariat of Education. While the workers and soldiers were fighting Kerensky’s troops at the approaches to Petrograd and the Military Revolutionary Committee was organising the struggle against the counter-revolution within the capital, the People’s Commissariat of Education launched its crusade to abolish illiteracy. The departments which this Commissariat set up give us a clue to the character of its work. Thus, an Extension School Department for out-of-school education was set up under the direction of Nadezhda Krupskaya. A department for training teachers was set up under the direction of L. R. Menzhinskaya. Other departments set up were a Department of Polytechnical Education, an Art Department and so forth. Commissars were appointed to supervise the museums and palaces in the capital and to arrange for the guarding of their treasures. Thus, a reliable guard was posted at the Alexander III Museum as early as October 25.

Two days later the workers and soldiers undertook to guard the Winter Palace and the Hermitage. The People’s Commissariat of Education arranged for the publication in large editions of Russian classical literature. The works of Tolstoi, Pushkin and Gorky—printed on the commonest paper of different shades in view of the acute paper shortage—were sold in tens of thousands of copies.

In its decrees the Council of People’s Commissars consistently pursued the policy of removing all the barriers that stood between the state administration and the masses of the population. By the decree promulgated on November 10, 1917, the division of the population into estates, and all its concomitant privileges, corporations, civil rank and titles were abolished, and a “single title,” common for all the inhabitants of Russia—citizen of the Russian Republic—was introduced.

A decree passed on November 18 ordered all the local Soviets to take “revolutionary measures to impose a special levy on all higher officials” and to “cut all excessively high salaries.”

Such were the first steps of the Great Proletarian Revolution in organising the new administration.

The decrees of the proletarian revolution were not ordinary acts of legislation. They were documents which formulated the program of the revolution; they proclaimed, in the form of legislative enactments, a program of action for the masses, the program of action of the Bolshevik Party. As Lenin subsequently stated:

“We had a period when passing decrees served as a form of propaganda. We were jeered at and told that we Bolsheviks failed to see that our decrees were not being carried out; the entire Whiteguard press was full of derision on this score. But this period was a legitimate one; it was the period when the Bolsheviks had just taken power and said to the rank-and-file peasants and to the rank-and-file workers: this is how we would like to have the state administered. Here is a decree, try it.”[27]

During this historical period of “initial discussion by the working people themselves of the new conditions of life and of the new problems,” as Lenin described it,[28] the inhabitants of the more remote districts of the country were still doubtful about the stability and durability of the new order. In a number of districts the old organs of administration, such as the town and rural councils, continued to exist parallel with the Soviets. To dispel these doubts and to remove this anomaly, Lenin, on November 5, on behalf of the Council of People’s Commissars wrote an appeal entitled “To the Population,” in the course of which he said:

“. . . remember that you yourselves are now governing the state. Nobody will help you unless you yourselves unite and take all the affairs of the state into your own hands. Your Soviets are henceforth organs of state power, fully authorised to decide all questions.”[29]

The All-Russian Central Executive Committee and the Military Revolutionary Committee sent emissaries to the provinces to instruct the local Soviets and to see that the decrees of the Council of People’s Commissars were put into operation.

[1] Minutes of Proceedings of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Cossack Deputies. Second Convocation, Published by the All-Russian C.E.C., Moscow, 1918, p. 44.

[2] V. I. Lenin, “State and Revolution,” Collected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. XXI, Book II, p. 173.

[3] Ibid., p. 171.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p. 181.

[6] F. Engels, “Critique of the Draft of the Social-Democratic Program of 1891,” Works of Marx and Engels, Russ. ed., Vol. XVI, Part II, Party Publishers, Moscow, 1936, p. 109.

[7] V. I. Lenin, “Several Theses,” Selected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. V, p. 155.

[8] J. Stalin, “Once Again on the Social-Democratic Deviation,” in On the Opposition, Articles and Speeches, 1921-1927, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1924, p. 520.

[9] V. I. Lenin, “Marx’s ‘Civil War in France,’” Lenin Miscellany, Russ. ed., Vol. XIV, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1930, p. 311.

[10] V. I. Lenin, “Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power?” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 518.

[11] Ibid., p. 522.

[12] Ibid., p. 523.

[13] V. Bonch-Bruyevich, In the Fighting Line in the February and October Revolutions, Second edition, Federatsia Publishers, Moscow, 1931, p. 134.

[14] A. A. Demyanov, “Jottings on the Underground Provisional Government,” Arkhiv Russkoi Revolutsii, Vol. VII, Berlin, 1922, p. 34.

[15] “From the People’s Commissariat of Education,” The Gazette of the Provisional Workers’ and Peasants’ Government, No. 3, November 1, 1917.

[16] M. Zelikman, “No File Number,” Prozhektor (The Searchlight), 1924, No. 3 (25), p. 10.

[17] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 1236, Catalogue No. 2, File No. 27, folio 40.

[18] “The Meeting of the Petrograd Soviet,” Izvestia of the Central Executive Committee and of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, No. 229, November 18, 1917.

[19] V. I. Lenin, “Speech in Memory of J. M. Sverdlov at the Special Session of the All-Russian C.E.C. on March 18, 1919,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXIV, p. 83.

[20] Decrees of the October Revolution (Government Acts Signed or Ratified by Lenin as Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars.) 1. From the October Revolution to the Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, Party Publishers, Moscow, 1933, pp. 28-30.

[21] “To the Toiling Mohammedans of Russia and the East,” Pravda, No. 196, November 22, 1917.

[22] J. Stalin, “Turkish Armenia,” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 689.

[23] Decrees of the October Revolution (Government Acts Signed or Ratified by Lenin as Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars.) 1. From the October Revolution to the Dissolution of the Constituent Assembly, Party Publishers, Moscow, 1933, p. 393.

[24] Compendium of Secret Documents from the Archives of the Former Ministry for Foreign Affairs, No. 2, Second edition, Published by People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, Petrograd, 1917, p. 1.

[25] V. I. Lenin, “Speech in Memory of J. M. Sverdlov at the Special Session of the All-Russian C.E.C. on March 18, 1919,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXIV, pp. 79-81.

[26] V. I. Lenin, “Speech on the Question of Forming a Supreme Council of National Economy,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXII, p. 108.

[27] V. I. Lenin, “Eleventh Congress of the R.C.P.(B.), Political Report of the Central Committee, March 27, 1922,” Collected Works, Russ. ed., Vol. XXVII, p. 255.

[28] V. I. Lenin, “The Immediate Tasks of the Soviet Government,” Selected Works, Eng. ed., Vol. VII, p. 344.

[29] V. I. Lenin, “To the Population,” Lenin and Stalin, 1917, Eng. ed., p. 646.

Previous: The Counter-Revolutionary Sortie of the Constitutional Democrats

Next: The Military Revolutionary Committee