The massacre of unarmed soldiers in the Kremlin stirred the people to the highest pitch of indignation.

The Military Revolutionary Committee, the Central Bureau of Trade Unions, the Moscow Committee of the Bolshevik Party and the Moscow organisation of the Polish and Lithuanian Social-Democrats issued a manifesto to the workers in the course of which they said:

“This is no time for work! On the 28th let us leave the factories to a man and at the first call of the Military Revolutionary Committee do everything that it orders.”[1]

“Show our enemies that the overwhelming majority of the population of Moscow is against them.”[2]

The proletariat unanimously responded to this call. All the Moscow factories came to a standstill. The workers on night shift went straight from their machines to their factory committees.

“Give us arms!”—demanded the workers.

The day shifts went to their Military Revolutionary Committees without going to their shops. Crowds of workers besieged the premises of the District Soviets.

“To arms!”—was the cry of the masses.

Red Guards lined up in squads of ten and hastened to the local Military Revolutionary Committees where arms were issued to them. Everybody rallied for the fight: men and women, Bolsheviks and non-party. On learning of the commencement of hostilities, a Bolshevik worker employed at the Ordnance Works telephoned the works’ committee and said:

“Take all the Bolsheviks off work and send them to the Revolutionary Committee to await orders.”

The Bolshevik group at these works, numbering about 300, lined up and marched to points indicated to them. The departure of these Bolshevik Red Guards caused alarm among the two thousand workers of the night shift who requested that a meeting be called. This was done and a brief report of the situation was made. Without wasting any time in debate, the workers hastened to the barricades. The women workers at once joined first-aid groups. Enthusiasm ran so high that even Menshevik workers, forgetting about their “neutrality,” joined the Red Guard.

Late at night workers from a factory outside Moscow arrived at the Headquarters of the Military Revolutionary Committee of the City District. The grim look on their faces, the flaming torches they held and the rifles which some of them carried, attracted universal attention.

“Who are you? Where are you from? And why have you come?”—were the questions fired at them by workers and soldiers.

“We heard that things were hot here and so we came to lend a hand,” they answered.[3]

The majority of them were non-party.

“Let’s get on with the job!”—they begged of the Military Revolutionary Committee.

The treacherous attack of the cadets incensed others besides the workers. A representative of the Zamoskvorechye District Committee of the Bolshevik Party was on Kaluga Square recruiting volunteers. Suddenly, out of the darkness a military unit emerged, armed with rifles, and led by two officers.

“Whiteguards!” was the thought that flashed through his mind.

One of the officers commanded: “Order arms!” and approaching the representative, saluted and enquired:

“Who represents the Chief of Staff here? We’re from the 196th Reserve Unit. We’ve come to place ourselves at your command.”

The two officers proved to be Captain Shutsky and Lieutenant Bogoslovsky. Incensed by the savage atrocity perpetrated in the Kremlin, they went over to the side of the revolutionary people.

Staff Captain L. I. Lozovsky, an Internationalist Menshevik, presented himself at the Headquarters of the Sokolniki District Military Revolutionary Committee together with his two sons.

“. . . I am not a Bolshevik,” he said, “but since the working class have come out on the barricades arms in hand, I cannot stand aloof.”[4]

Lozovsky and one of his sons died like heroes in the civil war.

Many intellectuals threw in their lot with the cause of the working class that day. Engineers presented themselves at the Headquarters of the District Military Revolutionary Committee offering their services.

Indignation also spread among the soldiers of the garrison. That day, October 28, a garrison meeting of Company Committees elected a Provisional Committee of Soldiers’ Deputies of ten men. The meeting also proclaimed the former Socialist-Revolutionary-Menshevik Executive Committee of the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies traitors to the cause of the revolution. The “Committee of Ten” forthwith issued an appeal to the rank-and-file soldiers calling upon them

“to render the Military Revolutionary Committee every support and obey only its orders. Orders emanating from Military Area Headquarters, or from the ‘Committee of Public Safety,’ are to be disregarded.”[5]

The “Committee of Ten” issued an order to muster army units for the protection of the Moscow Soviet, which occupied the premises of the former Governor-General of Moscow opposite Skobelev (now Soviet) Square. On the site where the new wing of the Moscow Soviet now stands there was a courtyard with stables and other outbuildings, and also two wings facing Chernishevsky Street.

On the evening of October 28, Skobelev Square was already under fire from all sides. The cadets were attacking from Okhotny Ryad, and from the side streets between Nikitskaya and Tverskaya Streets.

The Military Revolutionary Committee together with its Staff drew up a plan for piercing the Whiteguard ring and for launching an offensive.

The enemy occupied the central part of the city. This enabled him to manoeuvre freely and to transfer reserves to the weak sectors of his line. The telephone wires were also controlled by the cadets and this ensured the enemy regular communication. On the morning of October 28 the Whites captured the Telegraph Office, and this enabled them to communicate with General Headquarters and call for assistance. The enemy had an undoubted superiority in arms. The arsenal in the Kremlin and a large stock of rifles and machine guns had fallen into the hands of the cadets. The army food depot which they had captured supplied them with provisions.

After carefully studying the situation, the Military Revolutionary Committee resolved:

“To establish close connections with the districts and secure a base in one of them. To wage offensive operations in the centre, and guerilla warfare in the districts.”[6]

The battle of Moscow split up into a number of separate engagements in the different districts of the city. From all quarters came demands for arms and ammunition.

The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Kazan Railway ordered a search of all the railway cars on the lines. Red Guard Markin, a railway car inspector, discovered a number of cars loaded with rifles and immediately informed the Military Revolutionary Committee. The cars were opened and about 40,000 rifles were found. An engine was hitched to the cars and the train hauled to the railway workshops. A report was immediately sent to the City and Sokolniki Districts which at once sent motor trucks to take the rifles away. The supply of arms for the other districts was organised by the Party Centre. During that night and the following morning the rifles were brought to the city and distributed among the districts. The Simonovsky powder magazines were captured by the Red Guards of the Simonovsky Sub-District, and here ammunition was distributed. From that moment the arming of the workers and soldiers and their organisation in detachments was vigorously proceeded with.

First of all it was necessary to make the immediate rear secure. House No. 26, on the Tverskoi Boulevard, was the headquarters of the City Militia. This building abutted on both Bolshoi and Maly Gnezdnikovsky Streets, quite close to the premises of the Moscow Soviet, where the Military Revolutionary Committee had its headquarters.

This house was held by a force of about 200 well armed Whites. Furthermore, a detachment of mounted militia arrived, and during October 27 and 28 considerable numbers of militiamen from the stations which had been captured by the Bolsheviks trickled in singly and in groups. Ryabtsev, realising the necessity of retaining possession of this building in order to threaten the rear of the Red troops, sent an additional detachment of cadets with two machine guns. To these were added two detachments of university students commanded by a lieutenant.

In the courtyard of the same building the Militiamen’s Union had its offices. The union was on the side of the Military Revolutionary Committee and rendered it important service with its telephone. The Whites soon learned of this, raided the offices and arrested the union officials. On the captured telephone they intercepted some of the orders issued by the Military Revolutionary Committee.

To capture this building a special detachment was formed, consisting of the “Dvinsks,” a Cycle Unit, men of the 55th and 85th Regiments and Red Guards from the Michelson and other plants. The detachment, with one piece of artillery, took up its position on Strastnaya Square. From there it launched an attack along the Tverskoi Boulevard and the two Gnezdnikovsky Streets.

The approaches from Nikitsky Street through Chernishevsky and Bryusovsky Streets were held by cadet pickets. These were forced back and the attack was driven home by Red Guards and men of the 56th and 192nd Reserve Infantry Regiments.

The men of the 193rd Infantry Reserve Regiment which had guarded the Moscow Soviet the previous day were relieved by two companies of the 55th Infantry Reserve Regiment. Armed units of the Red Guard and soldiers from different regiments sent by the Party Centre from the districts arrived at the Moscow Soviet. Barricades were erected and trenches dug and the attack was developed from here in all directions.

That same day, October 28, a detachment of 50 workers from factory No. 38 was ordered by the Military Revolutionary Committee to occupy Gazetny Street and to drive towards Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street. Another detachment, consisting of men of the 56th Regiment, was ordered to advance along Bryusovsky Street.

The Gazetny Street detachment occupied house No. 7 in that street, and the Bryusovsky Street detachment occupied the Girls’ High School.

The first detachment dislodged the cadets from house No. 1 at the corner of Nikitskaya and Gazetny Streets and captured 36 rifles, 24 revolvers and 18 hand grenades. The enemy fled in panic.

This victory greatly encouraged the men.

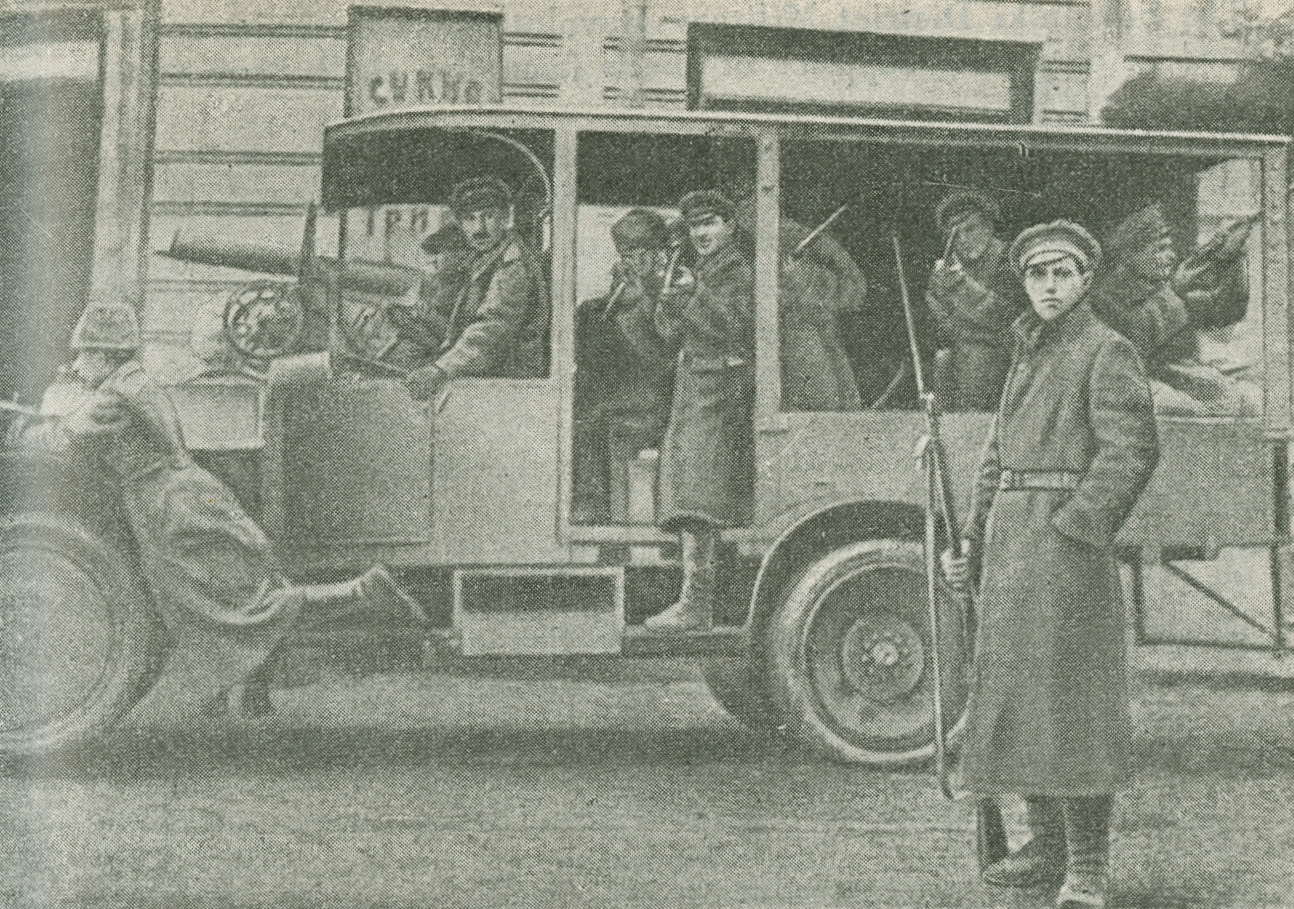

In the City District, Sadovaya Street, from Zemlyanoi Val to Karetny Ryad, was occupied by Red Guards and men of the 56th and 251st Regiments. The Sukharev Market was transformed into an armed camp, at the approaches to which trenches were dug. Barricades were erected at the corner of Sretenka Street. A large number of motor trucks were parked in the square outside the premises of the District Military Revolutionary Committee, which had its headquarters on the second floor of a tavern at the corner of Sukharev Square and 1st Meshchanskaya Street. The ground floor, the staircase and the corridors were thronged with soldiers and workers.

This building was a target for the cadets ensconced on the roofs of the high buildings in the vicinity. Often bullets sped through the windows and several people were hit. A soldier from the Spassky Barracks suggested that a machine gun should be mounted on the Sukharev Tower from where it would be possible to keep the square and the surrounding houses under fire. This proposal was adopted. Some soldiers stealthily hauled a machine gun to the tower and as soon as the cadets from the attic of a neighbouring house fired again the machine-gunners at once replied. The enemy fire from this quarter ceased.

“We can use strategy without the assistance of officers,” said the men proudly, pleased with the result of their work.

Red Guards, in groups of ten, after obtaining arms at the Headquarters of the City District, went off in motor trucks to the scene of the fighting. From here detachments of Red Guards went off to assist the Moscow Soviet and the 56th Infantry Reserve Regiment, who were trying to dislodge the cadets from the General Post Office, the Telegraph Office and the Inter-City Telephone Exchange.

The Military Revolutionary Committee of the City District was given the task of capturing the Central City Telephone Exchange. The first attack on this building which was launched from the direction of Bolshaya Lubyanka, was repulsed by the cadets.

The Sokolniki District Military Revolutionary Committee was instrumental in obtaining supplies of shells from the shell dumps at Rayevo Farm.

The Sokolniki tramcar depots set up their own Military Revolutionary Committee, which took over the job of forming and feeding Red Guards. This was in the nature of a “reserve regiment” of the October Revolution in Moscow. In a matter of three or four days it mustered about 3,000 worker Red Guards and put them through a short course of instruction in the use of arms. The canteen set up at the workshops fed about 1,500 Red Guards per day.

Nearly all the detachments which arrived during the days of the fighting from the environs of Moscow, such as Rayevo Farm, Kolchugino, Mytishchi and Kolomna, received their brief training in this “reserve regiment.”

The Basmanny and Blagusha-Lefortovo Districts were given the task of capturing the Alexeyevsky Military School, which in addition to the regular students was occupied by about 400 cadets well supplied with machine guns. The main fighting force in this area consisted of the workers of Heavy Siege Artillery Workshops. Of the 3,000 men employed there, 900 were Bolsheviks. They were organised on military lines and divided up in squads and companies. In the workshops there was a considerable number of guns, but no more than a hundred rifles. The well-armed cadets could capture the guns and it was therefore necessary to make haste. Trenches were dug at the approaches to the school and the men took up their positions. The cadets were called upon to surrender and were told that they would be allowed to go unharmed if they did so. In reply to this they suddenly opened fire, killing five and wounding ten workers. The Military Revolutionary Committees of both districts started a regular siege of the school.

The military units in this district consisted of a Cycle Battalion, three companies of the Telegraph and Searchlight Regiment, the 2nd Automobile Company and the 661st Home Guard Unit, the latter consisting of men over forty years of age. In the very first days of the insurrection the Cycle Battalion had been sent to guard the Moscow Soviet. Of the rest, the Blagusha-Lefortovo District had sent several detachments to the centre. It was necessary to protect the districts, to keep guard at Headquarters, and have guards posted at the factories; for all this men were required. Consequently, the siege of the Alexeyevsky Military School was conducted mainly by the workers of the Heavy Artillery Workshops and a small detachment of cyclists.

The workers in the districts were entirely on the side of the Revolutionary Committees. Very often workers’ wives seized individuals conducting agitation against the Soviet Government and brought them to the Headquarters of the Military Revolutionary Committee saying:

“Those who are against the Soviets are on the side of the bourgeoisie, and therefore, enemies of the people.”

The only people who were avowedly on the side of the cadets were the Students of the Higher Technical School. The Military Revolutionary Committee ordered a search to be made in this school and confiscated all the arms found there.

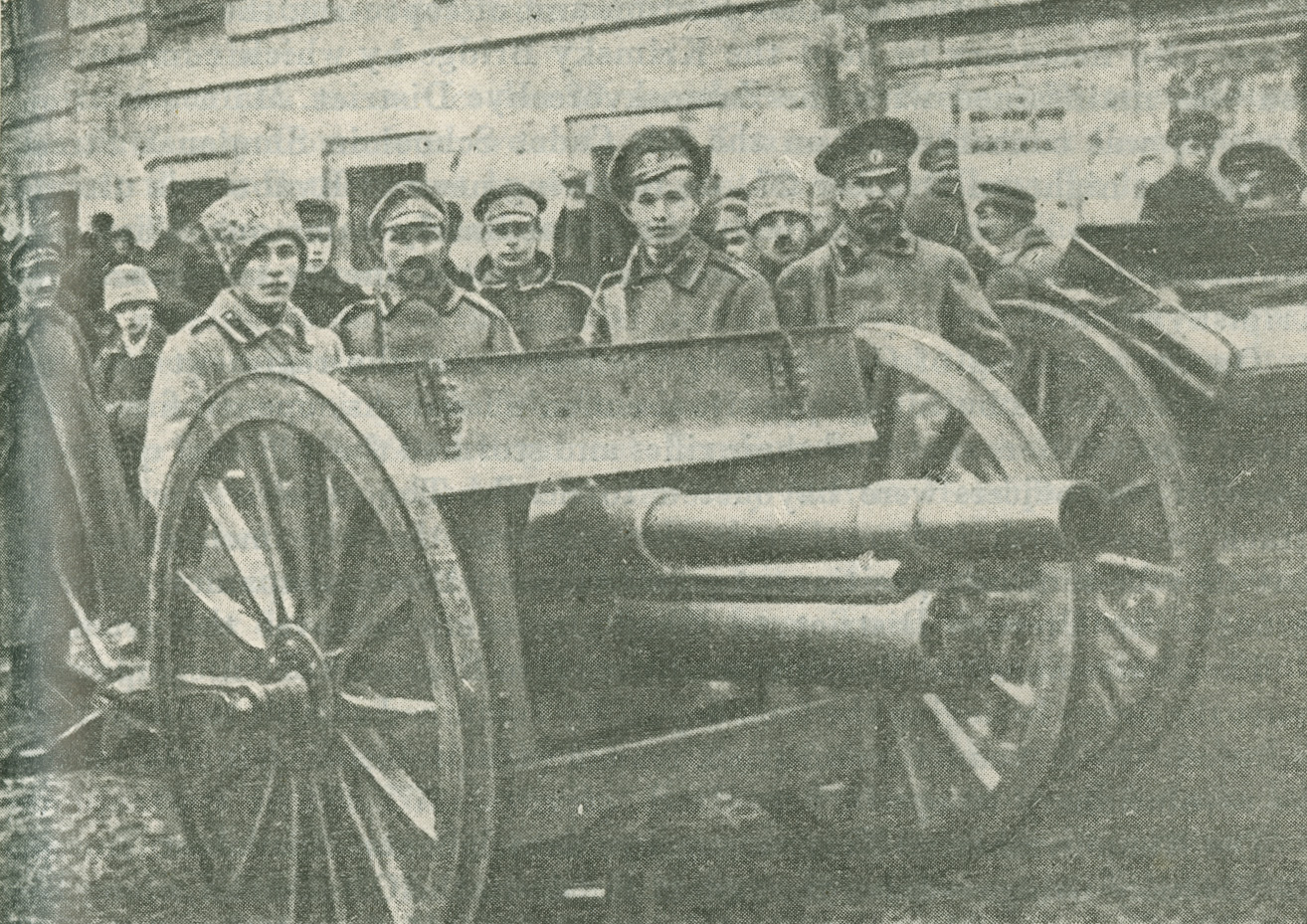

The cadets had transformed the Alexeyevsky Military School into a fortress. They honeycombed it with machine-gun nests. The thick walls of the buildings served as excellent protection against bullets. At a joint conference of the Military Revolutionary Committees of the Basmanny, Blagusha-Lefortovo and Rogozhsky Districts it was resolved to bombard the school. The workers of the Heavy Artillery Workshops chose Japanese howitzers for the purpose, but there were no means of hauling them into position. The workers took off their belts, wove them together, thus forming thick traces, and hauled the guns in that way. There were no range finders for the guns, as the officers had concealed them, so it was decided to haul the guns nearer to the building and to fire at close range, but this was prevented by a machine gun mounted at the main entrance to the building. Under a hail of bullets the Red Guards dragged a gun slowly and laboriously right to the bridge, about 400 paces from the entrance. This daring threw the cadets into confusion. The workers jumped up and fired over open sights at the school. After the second shell the machine gun was silenced. Meanwhile, a thorough search was made at the workshops and gun sights were found. With the aid of these a regular artillery bombardment of the school commenced.

In the Rogozhsko-Simonovsky District, factory after factory stopped work on the morning of the 28th, as soon as the workers heard the Military Revolutionary Committee’s call for a strike and the factory sirens sounded the alarm. The workers made their way to the two District Soviets, one in the Rogozhsky District and the other in the Simonovsky Sub-District. The first to arrive was the detachment from the Zolotorozhsky tramway depot. They were soon followed, hastening one after the other, by detachments from the Guzhon Works, the Podobedov Works and the Mars, Karavan, Danhauer and other factories. The working women employed at the Ostroumov, Keller and Sumin factories marched to the district headquarters to enrol in the first-aid units.

Everybody hurried to Alexeyevskaya Street, where the Rogozhsky Soviet, the Staff, and the District Committee of the Bolshevik Party were situated. No arms were available. On leaving the tramway depot the workers had said:

“When the rifles arrive, let us know; we’ll be around for them within ten minutes.”

And this is exactly what happened. When the first batch of rifles arrived the tramway men were informed. They hurried back to the depot, armed themselves and, fifty strong, went out to take up their positions in Varvarskaya Square. The same thing occurred at the Simonovsky Sub-District Soviet.

In the Zamoskvorechye District, where Professor Sternberg, the astronomer and a member of the Bolshevik Party, was at the head of the Military Revolutionary Committee, the Red Guards cleared the Kamenny Bridge of cadets and occupied the Krimsky Bridge. A detachment of the 193rd Regiment marched to the latter bridge through Zubovsky Boulevard and joined the Zamoskvorechye Red Guards. Red Guards also occupied the Commercial Institute after dislodging a force of Whiteguard university students: 87 of the latter were arrested.

The premises of the District Committee of the Bolshevik Party in the Zamoskvorechye District resembled an armed camp. All the rooms were crowded with workers whom “Dvinsks” and men of the 55th Reserve Infantry Regiment were showing how to handle rifles and revolvers. The workers were burning with eagerness to go into battle. The Red Guards of a number of factories took charge of definite sectors. The Michelson Works formed a Red Guard unit of 200 and a first-aid unit of 150. The workers of the Telephone Factory and the electric power station occupied the Chugunny Bridge and held it against the cadets. The workers at the power station switched off the light in the districts occupied by the Whiteguards. The Postavshchik Works sent a detachment of 50 men. The workers at the Danilov Textile Mills guarded the district against attacks by Cossacks likely to appear on the road from Kashira.

The workers at the tramway depot displayed heroic efforts. They transported arms, performed reconnoitring work and organised a splendid detachment of fighters. They boarded up the double windows of the tram cars and filled the space between with sand, thus making an improvised armoured train. With this they tried to launch an attack on the cadets on the other side of the Kamenny Bridge, but the cadets cut the trolley wire and the train came to a standstill. When shovels were needed to dig trenches, the tramway workers issued them from their workshops under receipt, and saw to it that they were returned. They felt that they were the masters and took great care of the workshop property.

In Kotly, in the rear of the district, some Cossacks were quartered, not many, as most of them had been sent to the central part of the city; but they might have caused panic by a sudden raid. The workers of the Danilov Textile Mills sent agitators among them. A meeting was held after which the Cossacks agreed to surrender their arms. The district was cleared of minor groups of Whites. When the rear had thus been made safe, all the armed detachments were sent to positions on the Moscow River.

In the Khamovniki District the cadets occupied School No. 5 in 1st Smolensk Street, near the Smolensk Market. The cadets also held the whole of the Arbat.

This was the district where the Central Army Food Depot which supplied food to the Moscow garrison was situated. The depot, on the corner of Ostozhenka Street, was occupied by the cadets. The district was given the task of holding the Bryansk Station and of capturing the food depot. It was also necessary to hold the Krimsky Bridge by which communication was maintained with the Zamoskvorechye District. Main attention, however, was concentrated on the 5th Cadet School in Smolensk Street.

Late at night on October 27, on receiving news of Ryabtsev’s ultimatum, the men of the 193rd Regiment immediately came out. They were reinforced by Red Guards and led in two detachments to attack the Krimsky Bridge.

On the morning of October 28, the officers of the regiment who had their quarters in a building opposite the men’s barracks, opened fire on the latter. The soldiers snatched their rifles and stormed the officers’ quarters. Many of the officers were bayoneted to death. The officers’ treacherous attack roused such indignation in the regiment that the men demanded that they be sent into position at once. At noon three companies marched through the Presnya District to Khodinka camp to cover the artillery.

The Chairman of the Committee of the 193rd Regiment led a company to assist the forces besieging the food depot. By combined assault the depot was captured. The last cadet motor truck loaded with provisions left under fire of the revolutionary troops.

The Khamovniki and Zamoskvorechye detachments—the latter crossing the Krimsky Bridge—drove the cadets far down the Ostozhenka, along Prechistenka Street to the very Headquarters of the Moscow Military Area in that street, and into a side street to the Ostozhenka. Here the cadets offered stubborn resistance. Reinforcements reached them and in the evening of October 28 the cadets launched an offensive in the Ostozhenka and in Prechistenka Streets. In the Smolensk Market this offensive was supported by an armoured car.

After the raid by the officers, the Dorogomilovo Revolutionary Committee was re-organised and quickly formed several detachments of workers, railwaymen and soldiers from the convalescent companies.

On the night of October 28, in response to the appeal of the Revolutionary Committee, 200 workers from the tramway depot arrived with tools and dug trenches near the Borodinsky Bridge, in the Plyushchikha, on the Smolensk Boulevard, and in Prechistenka Street.

That same night, in the Zamoskvorechye District, huge bales of cotton were brought up on a motor truck and under cover of these the Red Guards dug trenches in the Ostozhenka. Trenches were also dug in the Zamoskvorechye District near Kamenny Bridge, and barricades were put up near the Moskvoretsky Bridge.

The task allocated to the Butyrka and Sushchevsko-Maryinsky Districts was to prevent the infiltration of Whites into these districts, and to provide Red Guard reinforcements for the Moscow Military Revolutionary Committee.

The Presnya District was given the following tasks:

1. To prevent the Whites from reaching the Bryansk and Alexandrovsky Railway Stations.

2. To prevent the cadets from capturing the Khodinka camp and the artillery stored there.

At about 11 a.m. on October 28, members of the Presnya District Military Revolutionary Committee went to the Khamovniki District Committee to request that a detachment be sent to protect the artillery. In less than an hour a detachment of soldiers marched to the Khodinka. When they arrived they found that the 5th Battery had already left for the Moscow Soviet, cautiously making its way to the central part of the city. Near Strastnaya Square the battery was suddenly attacked by Whites, but the artillerymen drove them off with running rifle fire. On arriving at the square the artillerymen found the men of the 193rd Regiment. Sending their horses to the rear to take cover, the artillery opened fire on the City Militia Headquarters. The first gunfire was heard in the central part of the city.

This cannonade greatly raised the spirits of everybody in the Presnya District. New detachments were quickly formed and these joined in the attack along the Sadovaya line from Karetny Ryad to the Novinsky Boulevard.

The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Railway District had its headquarters in the Nikolayevsky Railway Station, in the Sokolniki District. This district was the converging point of the most important railways—the Yaroslavl, Kazan and Nikolayevsky. As now, the Nikolayevsky Station had direct connection with the Kursk Railway Station. The Moscow Bureau of the Executive Committee of the Railwaymen’s Union had its offices in the Nikolayevsky Station.

There was no fighting at the railway stations, except for the Bryansk Railway Station, but the Military Revolutionary Committees of the various railways rendered excellent service during the Moscow insurrection: 1) They occupied the stations despite the “neutrality” of the Railwaymen’s Executive; 2) They prevented the movement of White troops to Moscow; 3) They established communication with Petrograd through the Yaroslavl Railway Station; 4) They found about 40,000 rifles at the Kazan Railway Station; 5) They completely isolated the Moscow Bureau of the Railwaymen’s Executive, and on the Kursk Railway the Military Revolutionary Committee arrested the compromising railway committee; 6) The Military Revolutionary Committee of the Railway District sent all its detachments free from other duty to the central part of the city. The railwaymen Red Guards of those lines which ran through the fighting area took an active part in the fighting.

By the night of October 28, the position of the Military Revolutionary Committee had greatly improved. The cadets had been unable to extend the area they occupied; on the contrary, they were almost completely surrounded, and the workers’ detachments were pressing them to the central part of the city. All the railway stations were in the hands of the revolutionary forces. The cadets received no outside reinforcements, whereas new revolutionary detachments kept on arriving at the Moscow Soviet. Outside the Moscow Soviet guns were in position, and their very presence there roused the spirit of the men. But the main thing was that detachments were now being formed on a mass scale. If the Military Revolutionary Committee sent a request to a given district for a hundred men, three hundred arrived. The masses of the people rose for the struggle. The districts hummed like disturbed beehives; and the initiative they displayed in organising their forces was unprecedented.

On the night of October 28, Lieutenant Rovny again communicated with General Headquarters. Of his former arrogance there was no longer a trace.

“The centre, for the most part, is in our hands,” he reported, “except for the district adjacent to the Governor-General’s residence [i.e., the Moscow Soviet—Ed.].

“The suburbs are in the hands of the Red Guard and the mutinous section of the soldiers.

“Zamoskvorechye is not within the sphere of our operations. . . .

“In view of the insufficiency of forces and the fatigue of the troops who are loyal to the government, it is not possible to clear Moscow of insurgents speedily.”[7]

Rovny concluded his melancholy report with a request for speedy assistance.

General Headquarters, however, was well aware of the mood of the Whites in Moscow. Dieterichs concluded the conversation with a threat. He told Rovny “for his personal information” that he had received instructions if necessary:

“. . . to remove from the actual performance of duties every officer without exception. . . .”[8]

After his conversation with Moscow Dieterichs called up the Western Front and urgently requested that assistance be sent to Moscow at once, and from the nearest district. Western Front Headquarters replied that the Committee in Minsk had forbidden them to do that.

“But you can send forces from the Minsk Area and not from the front,” pleaded Dieterichs.

“The situation here, in the rear, is that everywhere the Bolsheviks have risen in revolt and are seizing power,” answered Western Front Headquarters. “Troops are needed everywhere. Evidently there are reserves in Kaluga, but the Commander-in-Chief of the Area is demanding the dispatch of troops from Kaluga to Smolensk, Rzhev and Vyazma. I will immediately report to the Commander-in-Chief and inform you of the result.”

“Please do, it is very important. Very important, I repeat a second time,” said Dieterichs, imploringly.[9]

With great difficulty they managed to find a unit. Orders were issued to send to Moscow three squadrons of the Nizhni-Novgorod Dragoons, who were either in Kaluga or else on the way to Smolensk; nobody knew for certain where they were.

On the morning of October 29 the revolutionary forces launched a decisive offensive. A detachment of 70 cyclists occupied the Maly Theatre. The City Militia Headquarters were captured. The siege of these premises had been greatly hindered by the fact that the approaches to them from Strastnaya Square had been under the fire of the cadets who occupied the Nikitsky Gate. Rising above the premises was a tall building, No. 10 Maly Gnezdnikovsky Street, the roof of which was surmounted by a tower. The Red Guards hauled a machine gun to this tower and poured a hail of bullets into the courtyard of the City Militia Headquarters. Artillery fire was opened from Strastnaya Square and a combined assault was launched against the premises. After the first successful gun shot they were stormed by a Red detachment.

With a loud cheer a detachment of soldiers raced through the boulevard and the adjoining streets and reached the windows of the first floor of the Militia Headquarters. The commander of the detachment ordered the men to lie down in front of the railings and open fire. The men were just about to do so when the Red Guards rushed forward, smashed the windows with the butts of their rifles and forced their way into the premises. The soldiers followed the Red Guards. This bold assault caused utter panic among the cadets, who had already been scared to death by the machine-gun and artillery fire. They stopped shooting and literally poured down the stairs from the upper floor. About two hundred well armed cadets and university students surrendered to a detachment of fifty or sixty men. Escorted by a half score of men, they were marched off to the Moscow Soviet.

The combined assault on the City Militia Headquarters was crowned with success.

In this bold attack Sergei Barbolin, twenty years of age, and Zhebrunov, nineteen years of age, the youth organisers in the Sokolniki District—perished. Barbolin was a capable and energetic organiser, ready to lay down his life for the revolution. He performed an enormous amount of work among the youth and spent whole days in the factories. Zhebrunov had been the breadwinner of his family since the age of fifteen, and had tramped nearly all over the country in search of work. Every spare moment he could find he spent at his books, and next day shared his newly acquired knowledge with his comrades. The two youth organisers were close friends and were known among their comrades as “the inseparables.” In the days of the fighting they carried out a variety of functions, but they were not satisfied with this. They were eager to go into battle. Arming themselves with rifles, they left their district and reported at the centre. They were sent to join the detachment that was to storm the City Militia Headquarters. A burst of machine-gun fire killed Zhebrunov outright and mortally wounded Barbolin.

The Red Guard units consolidated their positions in the side streets leading to the Moscow Soviet and advanced along Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street, which became the border line between them and the cadets. That same morning the revolutionary forces stormed and recaptured the General Post Office and Central Telegraph Office. On regaining possession of the Telegraph Office the Red Guards discovered that the Telegraph Employees’ Committee had intercepted the telegrams of the Soviet Government and that it had disconnected the towns where the revolution had been successful. Some of the members of the Committee were arrested and the matter was reported to the Military Revolutionary Committee. The latter sent a special Commissar to the Telegraph Office.

In the Lefortovo District, after the workers of the Heavy Artillery Workshops had found the gun sights, the artillery fire became more effective. Shells burst in the premises of the Alexeyevsky Military School. The majority of the cadets and members of the staff who were holding the place, surrendered, but the cadets of the senior classes continued to offer resistance.

In the Khamovniki District small groups of Red Guards of three to five men, threading their way through back doors and courtyards of houses, filtered into the enemy’s rear and suddenly attacked the cadets with hand grenades and rifle fire. In the Ostozhenka, the men of the 193th Regiment mounted a mortar in their trench, which was only about two hundred paces from the enemy’s lines. A rapid fire was kept up: to raise one’s head above the trench meant death.

The Red Guards of the Zamoskvorechye District, where fighting had ceased for a time, occupied the bridges across the Moscow River. Armed detachments were sent to conduct joint operations with the Khamovniki District against Military Area Headquarters. Furthermore, one of the most important functions of the Zamoskvorechye District was to ensure the steady functioning of the electric power station, and this was successfully fulfilled.

The exceptional importance of the Zamoskvorechye District during the October days lay in the fact that in that district were concentrated numerous factories which supplied men for the Red Guard units. On October 29, the Party Fighting Centre took up its headquarters in the Commercial Institute in that district; and here the editorial offices of the Sotsial-Demokrat and of Izvestia of the Moscow Soviet were also situated.

In the Presnya District the Military Revolutionary Committee, on October 29, organised and armed as many as 600 men. Here the 1st and 2nd Militia Stations were occupied, and a Cossack patrol was captured in Voskresensky Field.

On the night of October 29 three-inch guns from the 1st Artillery Reserve Brigade arrived in the Presnya District. One of them was mounted in Kudrinskaya Square and fire was opened at the belfries of the Kazan and Devyatinsk Churches, which were occupied by cadets. Another gun was mounted near the Zoological Gardens and a third near the Gorbaty Bridge.

An extremely important function of this district was to hold the Alexandrovsky—now Byelorussian—Railway Station, which the Military Revolutionary Committee on that line had occupied without meeting with any resistance. The operations of the armed forces of the Military Revolutionary Committee developed successfully. The cadets and officers surrendered an extremely important position in the centre of the city like the City Militia Headquarters.

At 9 p.m. on October 29, Military Area Headquarters reported to General Headquarters as follows:

“. . . the enemy’s forces are growing and he is hourly becoming more audacious.

“The suburbs are entirely beyond our reach.

“. . . Today the Bolsheviks occupied all the railway stations, and in the centre of the city they have occupied the City Militia Headquarters, as well as the General Post Office and Central Telegraph Office, which had to be abandoned owing to the fatigue of the detachment which had successfully repulsed repeated assaults. The detachment had to be transferred to the Telephone Exchange.

“The Alexeyevsky School, where a company of cadets has remained, is stubbornly defending itself, although the Bolsheviks’ heavy artillery has destroyed the upper part of the building and has caused fires. . . .

“. . . Assistance is urgently needed as, without prospects of support, the situation is by no means promising.”[10]

The further success of the Red forces was fully assured.

[1] “To the Workers,” Izvestia of the Moscow Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, No. 199, October 28, 1917.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Assya, “October 1917 in the City District,” in The October Days in Moscow and Districts, Moskovski Rabochi Publishers, Moscow, 1922, p. 61.

[4] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II, of “H.C.W.”

[5] Sotsial Demokrat, No. 195, October 28, 1917.

[6] “The Moscow Military Revolutionary Committee,” Krasny Arkhiv, 1927, Vol. 4 (23), p. 70.

[7] “General Headquarters and the Moscow Committee of Public Safety in 1917,” Krasny Arkhiv, 1933, Vol. 6 (61), p. 35.

[8] Ibid., pp. 35-36.

[9] Ibid., p. 37.

[10] Ibid., p. 38.

Previous: The Surrender of the Kremlin

Next: Armistice