N THE NIGHT of October 25, the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, having overthrown the bourgeois government, transferred power to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets. The delegates to this Congress had begun to arrive in Petrograd on October 17 and 18, as it had been originally intended to open the Congress on the 20th. The Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik leaders of the Central Executive Committee accommodated the delegates in different parts of the city with the definite aim of preventing them from uniting. This ruse failed, however. The hostels at which the delegates were quartered were very quickly transformed into animated political clubs. The delegates also visited the factories and regiments and in the tense atmosphere of the capital, the illusions which some of them harboured about the possibilities of effecting a compromise, were dispelled. In the evening, the delegates would gather in their hostels and share their impressions of the busy day. Everywhere, lively discussions and debates went on, and most of the delegates, although not officially associated with the Bolshevik Party, whole-heartedly expressed their opposition to the Provisional Government. Even non-party delegates were carried away by the fighting spirit that prevailed in the capital and among the Bolshevik delegates.

N THE NIGHT of October 25, the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Petrograd Soviet, having overthrown the bourgeois government, transferred power to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets. The delegates to this Congress had begun to arrive in Petrograd on October 17 and 18, as it had been originally intended to open the Congress on the 20th. The Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik leaders of the Central Executive Committee accommodated the delegates in different parts of the city with the definite aim of preventing them from uniting. This ruse failed, however. The hostels at which the delegates were quartered were very quickly transformed into animated political clubs. The delegates also visited the factories and regiments and in the tense atmosphere of the capital, the illusions which some of them harboured about the possibilities of effecting a compromise, were dispelled. In the evening, the delegates would gather in their hostels and share their impressions of the busy day. Everywhere, lively discussions and debates went on, and most of the delegates, although not officially associated with the Bolshevik Party, whole-heartedly expressed their opposition to the Provisional Government. Even non-party delegates were carried away by the fighting spirit that prevailed in the capital and among the Bolshevik delegates.

By October 22, 175 delegates had arrived in Petrograd. Of these, 102 were Bolshevik, or shared the Bolshevik point of view.[1] Every day, representatives of the Central Committee of the Party visited the hostels, called out the Bolshevik delegates and sent them to the working-class districts of Petrograd to address meetings in the factories and the regiments. One of the most eloquent of these speakers was S. M. Kirov, the delegate from North Caucasus, who addressed several meetings a day.

At these meetings the Bolshevik propagandists described the growth of the revolutionary movement in their respective districts. Y. Z. Yerman, for instance, reported on the growth of the revolution in Tsaritsyn. Delegates from the industrial regions read the instructions they had received, in which tens of thousands of proletarians demanded the transfer of power to the Soviets. The Bolshevik soldier delegates related how eagerly the men in the army clutched at every piece of information about the maturing revolution. Kerensky’s name, they said, was always pronounced with derision and imprecations. Thus, the people attending these enthusiastic meetings obtained a picture of what was going on in the Urals, the Donets Basin, the Volga Region, the Ukraine and at the front—in fact, throughout the country, and from what the Bolshevik delegates related in their speeches the Petrograd workers became convinced that they were not alone, that they could rely on the support of the working class of the country and the entire poor section of the peasants.

Of the 318 provincial Soviets which were represented at the Second Congress, only 59 had expressed themselves in favour of the “power for democracy,” slogan and 18 had passed indefinite resolutions, partly in favour of “power for democracy” and partly of “power for the Soviets.” Delegates from 241 Soviets arrived for the Congress with Bolshevik mandates; 241 Soviets had unreservedly demanded: “All power to the Soviets!”

Such was the temper prevailing in the provinces.

As the opening day drew nearer the delegates assembled more often in the Smolny.

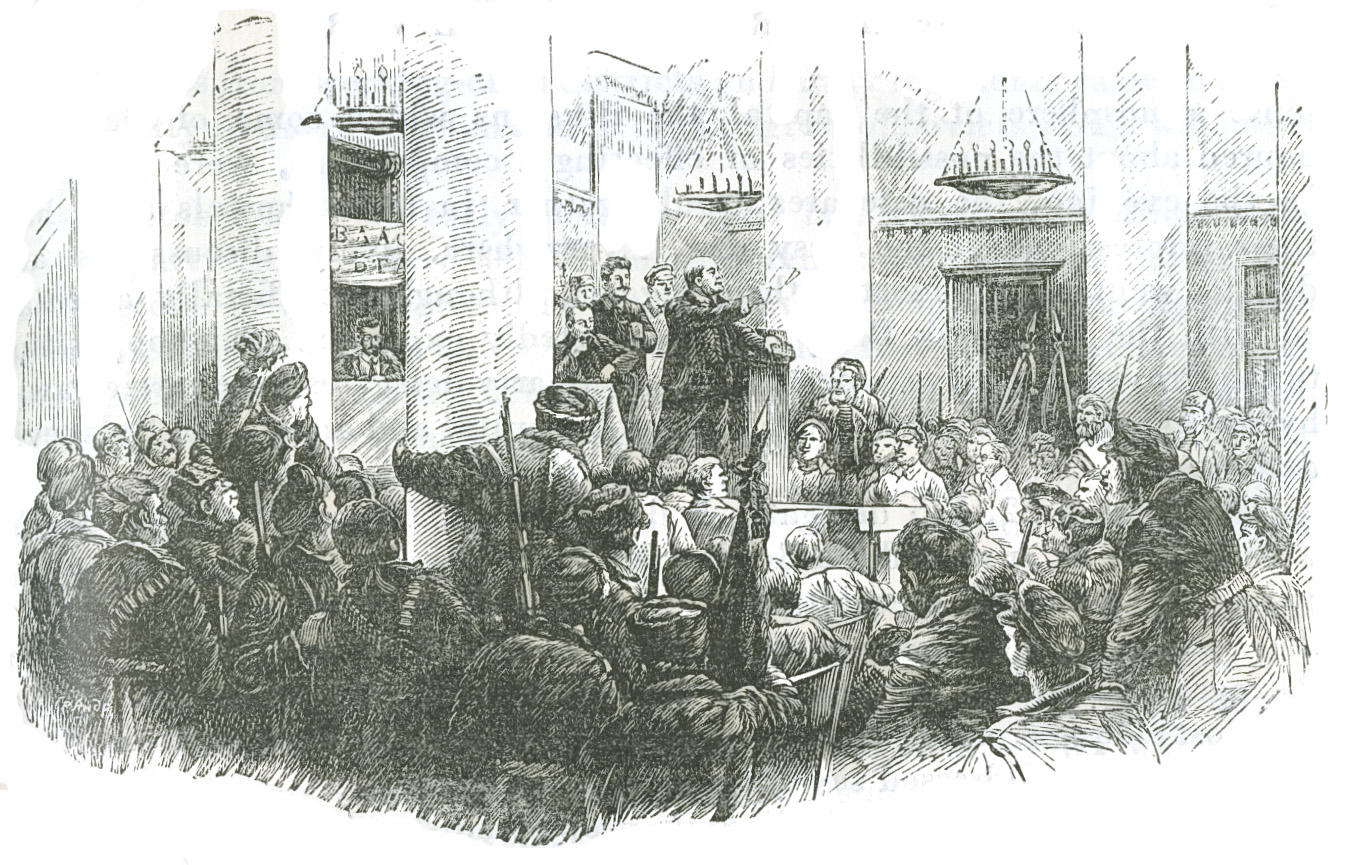

Delegates from the trenches, from the factories and rural districts came with grim and anxious faces. The dimly lit corridors of the Smolny, darkened still more by clouds of tobacco smoke, were thronged with workers in overalls, soldiers in grey and sailors in black greatcoats, and peasants in their homespun clothes.

Delegates from working-class districts and army regiments came to attest their loyalty to the revolution and to the Congress of Soviets which was about to open.

On October 25 from early morning until late at night meetings of the various party groups were held in the different rooms of the Smolny. The largest group at the Congress was the Bolshevik group, constituting a clear majority of the delegates, i.e., 390 out of a total of 650 who had arrived at the opening. Several score other delegates arrived after the Congress had opened.

The Bolshevik group had its office in a large room on the first floor of the Smolny. This room, furnished with only a table and several chairs, was filled with Bolshevik delegates who kept arriving in a constant stream. Many of them squatted near the walls on the floor.

Spirits ran high, but everybody was calm and confident. Many of the Bolshevik delegates had spent the last few nights before the Congress in this room in the Smolny. Spreading newspapers, overcoats or greatcoats on the floor, they dozed for two or three hours, and at the break of day were ready once again to carry out the tasks entrusted to them by the Party. Many of them were armed with revolvers, rifles and sabres, and had hand grenades dangling from their belts.

The composition of the Second Congress of Soviets was a striking demonstration of how far the Bolshevik Party, during the seven months of the Provisional Government, had succeeded in convincing the people that without a proletarian revolution the question of land and peace could not be settled.

The Mensheviks and Right Socialist-Revolutionaries, who had been the strongest parties at the First Congress of Soviets, came to the Second Congress as miserable bankrupts. Only a very short period had been necessary to expose these false friends of the people to the workers and peasants as traitors and deserters.

The Right Socialist-Revolutionaries, together with the Centrist Socialist-Revolutionaries, constituted a group of 60. The other members of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party followed the “Lefts.” Later on in the course of the Congress, the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, after winning over a section of the Right and Centrist Socialist-Revolutionary delegates from the provinces, constituted a group of 179, the second largest at the Congress. At the opening of the Congress the Mensheviks of different trends, including the Bund, numbered about 80.

The leaders of the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries wandered through the corridors of the Smolny, pale, bewildered and depressed. They were generals without armies. At their group meetings their delegates had split up into innumerable coteries. They had decided not to take part in the Congress, but the temper of the masses was so revolutionary that the rank and file had openly opposed the decision of their leaders.

At the meeting of the Menshevik group the debate went on for hours, but their leaders failed to secure unity. An adjournment was made in order to hold a meeting of the Central Committee of the Menshevik Party. When the group meeting was resumed at 6 p.m., Dan informed the delegates that the Central Committee of the Menshevik Party had decided to repudiate responsibility for the revolution which had been made and, therefore, the Menshevik Party could not stand behind Bolshevik barricades. The Central Committee recommended that the group should take no part in the proceedings of the Congress and decided to open negotiations with the Provisional Government with a view to forming a new government.

The Socialist-Revolutionary group had also discussed the question of whether to take part in the Congress proceedings or not. The Central Committee of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party had recommended that the group should keep away, but by a majority vote the group decided not to leave the Congress.

In order to keep control over the delegates from the front the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks formed what they called a Front Group. Taking advantage of the absence from the front of the Bolshevik delegates, who had left to attend a meeting of the Bolshevik group, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks succeeded by a vote of sixteen to nine, with six abstentions, in persuading this so-called Front Group to adopt a resolution declaring against participation in the Congress.

These group meetings lasted until late at night.

With the consent of all the groups it had been arranged to open the Congress at 8 p.m.; but at 10 p.m. the Menshevik group was still in session. The Bolsheviks sent two representatives to the Mensheviks to inquire when they could be expected in the hall. The Mensheviks replied that they would be engaged at least another hour.[2]

At last, at about 11 p.m., a group of members of the outgoing Central Executive Committee of Soviets—Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries—took their seats on the platform.

In spite of the lateness of the hour, the Smolny was as animated as ever. The hall in which the Congress was held was crowded and ablaze with light. Delegates stood on the bases of the pillars and sat on window-sills. The gangways and the doorways were packed when at 10:40 p.m. a stout figure in military tunic with a Red Cross on his sleeve mounted the platform. This was the Menshevik Dan, who, on behalf of the outgoing Central Executive Committee, declared the Congress open.

It seemed, however, that the only reason why the Mensheviks and their inseparable companions, the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries, had appeared at the Congress was to display their counter-revolutionary faces. Right from the very outset they brazenly supported the counter-revolution, the hotbed of which—the Winter Palace—the Petrograd workers and soldiers were at that moment taking by storm.

In opening the Congress Dan said:

“I am a member of the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee, but at this moment our party comrades are under fire in the Winter Palace, selflessly performing their duty as Ministers.”[3]

The Ministers, with whom Dan thus expressed his solidarity, were at that moment summoning troops from the front for the purpose of suppressing the Petrograd proletariat. They had already sent Kerensky to the front for the purpose of bringing Cossack units to Petrograd. They had appointed the Constitutional Democrat Kishkin “dictator,” and had vested him with extraordinary powers to “restore order” in Petrograd.

“Without any speech making,” said Dan, “I declare the session of the Congress open and propose that we proceed to elect a Presidium.”[4]

The Bolsheviks moved that the Presidium be elected on the basis of proportional representation, but the Mensheviks and Right Socialist-Revolutionaries declined to nominate their representative. The International Mensheviks also declared that they would “abstain” from taking part in the election of the Presidium of the Congress “until certain questions are cleared up.”[5]

They moved that “the question of how to avert inevitable civil war be taken as the first item for discussion.”[6]

The gaunt and irate figure of Martov, the Menshevik leader, appeared on the platform. In a hoarse voice he began by hurling abusive epithets at the Bolsheviks, described the victorious uprising of the proletariat as a “conspiracy,” and called upon the revolutionary workers and soldiers to come to their senses before it was too late, Martov actually suggested that the delegates should go out into the streets of Petrograd to persuade the insurgent workers and soldiers to disperse to their homes.

On behalf of the Internationalist Mensheviks Martov recommended that the Congress should

“elect a delegation to negotiate with other Socialist parties and organisations with a view to securing the cessation of the conflict.”

He claimed that the only way to avert civil war was to set up “a united democratic government.”[7]

The representatives of “the other Socialist parties and organisations” with whom Martov suggested that an agreement should be reached concerning the formation of a “united democratic government” were present at the Congress, and if the Mensheviks had sincerely wished to act in accordance with the wishes of the overwhelming majority of the working people, they would have taken part in the proceedings of the Congress and have submitted to its decisions. But Martov’s proposal had something entirely different in view. The “cessation of the conflict which had commenced” that the Mensheviks demanded meant raising the siege of the Winter Palace, freedom of action for the beleaguered Ministers headed by the “dictator” Kishkin, and giving the Provisional Government time to obtain reinforcements from the front and to mobilise the counter-revolutionary forces in Petrograd itself. Martov’s proposal was tantamount to direct support for the counter-revolution.

He was supported by the other vacillating groups at the Congress—the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Front Group. The Bolshevik group declared that it

“had no objection whatever to Martov’s proposal. On the contrary it was interested in having all the groups express their views on current events and submit their proposals for a way out of the situation.”[8]

In this sense, viz., that the various groups at the Congress should express their attitude toward the events of the day, Martov’s proposal was adopted unanimously.

The resolution as adopted could not possibly satisfy the Mensheviks. The Congress had side-tracked the main point of their proposal—“cessation of the conflict which had commenced.” One after another, representatives of the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks demanded the floor for the purpose of making declarations on a “motion of urgency.” Spluttering with impotent rage they continued to howl about the “plot” and the “adventurism” of the Bolsheviks. From the platform of the Congress they openly declared civil war against the Soviet Government. The Menshevik Y. A. Kharash, speaking as the representative of the Committee of the Twelfth Army, said:

“The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries deem it necessary to dissociate themselves from all that is taking place here, and to rally the social forces for the purpose of resisting attempts to seize power with all their might.”[9]

He was followed by G. D. Kuchin, a Menshevik army officer, who claimed to speak “on behalf of the Front Group.”

“From now on the provinces will be the arena of the struggle, and that is where the forces must be mobilised,” said this Menshevik emissary.

“In whose name are you speaking?” came the retort from some delegates in the hall. “When were you elected? What do the soldiers say?”[10]

Kuchin mentioned the Committees of the Second, Third, Fourth, Sixth, Seventh and other Armies. Assuming a threatening tone, he tried to intimidate the Congress by stating that the 20 armies at the front would come to Petrograd where they would not leave a stone upon stone. He painted a lurid picture of the front being opened and of Russia hurtling to her doom. In proof of his statements he read the resolutions passed by the Army Committees which were full of similar threats.

Tense silence followed. A chill seemed to have seized the delegates. The units at the front did indeed represent a formidable fighting force. Supposing all that this officer had said was true?

But suddenly the spell was broken by a loud and confident voice. A soldier from the front, in a mud-stained greatcoat, pressed his way to the platform.

“These men,” he said, “are expressing the opinion of the cliques in the Army and Front Committees. The army has long demanded new elections of these committees. . . . The men in the trenches are waiting impatiently for the transfer of power to the Soviets.”[11]

And amid a storm of enthusiastic applause the soldier waved a batch of resolutions passed by the men at the front.

The next speaker was the representative of the Lettish Rifles. He said:

“You have heard the statements of two representatives of Army Committees. These statements would have been of some value if those who made them really represented the army. . . . They do not represent the soldiers. . . . Let them get out! The army is not with them!”[12]

Kharash and Kuchin were typical representatives of the Army Committees which had held office without re-election since practically the first days of the February Revolution. The mass of rank-and-file soldiers rightly regarded them as agents of the General Staff, which had undergone hardly any change since the fall of the autocracy. From the moment the Congress opened a struggle began between the representatives of the higher army, peasants’ and railwaymen’s organisations who spoke from the platform, and the rank-and-file worker, soldier and peasant delegates who filled the benches and gangways of this vast hall. These rank-and-file delegates scoffed at the statements made by the committee men who addressed the Congress as if it were an enemy camp. The cries of indignation that came from all parts of the hall in reply to the threats of the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries were but a faint echo of the anger which the policy of these social-compromisers had roused throughout the country. Kuchin and the other committee men represented a stage of the revolution that had long passed away.

“Traitors! . . . You are speaking on behalf of the General Staff and not of the army!”—were the cries hurled at Kuchin from the delegates’ benches.

In reply to his call to “all politically conscious soldiers” to leave the hall hundreds of soldiers retorted:

“Kornilovites!”

The abusive language used by Kharash and Kuchin in their speeches was repeated in the declarations read by the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, which breathed impotent rage at the Socialist revolution, and abounded in counter-revolutionary abuse of the Bolsheviks.

In their declaration the Mensheviks referred to the Great Socialist Revolution as a “gamble” and a “conspiracy,” which would “plunge the country into internecine strife” and would “lead to the triumph of the counter-revolution.” The only way out of the situation, the Mensheviks maintained, was “to negotiate with the Provisional Government with a view to the reorganisation of the government.”[13]

The Socialist-Revolutionaries associated themselves with the Mensheviks. Their declaration, read by Hendelmann, was in complete accord with that of the Mensheviks and described the October insurrection as “a crime against the country and the revolution.”[14]

Both the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries stated in their declarations that they would leave the Congress.

Abramovich, the representative of the Bund, stated that his group had also resolved to leave the Congress. Continuing, he said that the Mensheviks, the Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies and the members of the City Duma had all decided to die by the side of the government and, therefore, were all going to the Winter Palace to face the fire. He invited all the Congress delegates to join them.

“We’re not going that way!” came the reply from the delegates’ benches.

The Mensheviks, Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and Bundists thereupon withdrew from the Congress, to which they had come for the sole purpose of issuing from its platform a call to the counter-revolutionary forces.

To reach the exit from the platform, the leaders of the compromisers had to walk down the length of the hall, and as they made their way through the dense crowd of delegates they were greeted on all sides with jeers and cries of:

“Deserters! Traitors! A good riddance!”

The Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik leaders failed to carry even their own supporters with them. The rank-and-file members of the compromising parties continued to swing to the left. The Menshevik group had registered 80 members and the Right Socialist-Revolutionary group 60. It might have been expected that 140 delegates would have left the Congress with the leaders. But some of the Socialist-Revolutionary delegates joined the Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary group, which in the course of one night had grown from 7 to 21. Some of the Mensheviks went over to the United Internationalists who remained at the Congress. The United Internationalists group increased from 14 to 35. Many of the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and non-party delegates joined the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, whose group increased to 179, whereas on the eve of the opening of the Congress the Socialist-Revolutionary delegates of all shades had numbered 193. Thus, only 70 delegates left the Congress. As the Congress proceeded the compromisers were still further isolated. Not a few rank-and-file members of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik groups deserted their leaders.[15]

A little later the Internationalist Mensheviks left the Congress. In spite of the fact that the conduct of the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries had clearly shown that they were hostile to the revolution, the Internationalist Mensheviks continued strongly to insist that it was necessary to reach an agreement with them for the purpose of forming a united democratic government.

Soon after the departure of the compromisers the dull booming of distant guns was heard in the hall. The delegates turned to the windows, beyond which, in the dark October night, the last act of the great insurrection—the assault on the Winter Palace—was drawing to a close.

The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks re-appeared in the hall and, their faces distorted by panic and rage, ran to and fro among the delegates, shouting that the Bolsheviks were bombarding the Winter Palace. Abramovich again mounted the platform and, wringing his hands hysterically, appealed to the Congress to come to the aid of the members of the Provisional Government, among whom there were representatives delegated by the Menshevik Party.

Abramovich was followed by Martov.

“The information just conveyed to you still more imperatively demands that we should take decisive measures,” he began, but was interrupted by voices from the hall:

“What information? Why are you trying to scare us? You ought to be ashamed of yourself. These are only rumours.”

“We hear not only rumours here. If you come nearer to the windows you will hear the sound of guns.”[16]

Terrified by the gunfire, Martov accused the Bolsheviks of having hatched a military plot and of causing bloodshed. In conclusion, his face twitching nervously, he read a declaration calling for the formation of a committee to secure a peaceful solution of the crisis and for the suspension of the Congress until this committee had completed its labours.

No sooner had the shrill voice of the Menshevik leader died down than the Socialist-Revolutionary representative of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies appeared on the platform and gave vent to the same “exhortations.” He appealed to the delegates not to take part “in this Congress,” but to go to the Winter Palace where

“three members of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies, including Breshko-Breshkovskaya, now were. We shall go there at once to die side by side with those whom we have sent to carry out our will.”[17]

A handful of members of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies left the hall and accompanied the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks to the Winter Palace. As they went out a sailor from the Aurora mounted the platform and in a bantering tone shouted:

“Don’t be afraid! We’re using blank shells.” This representative of the Aurora repeated this assurance to the delegates and added that the sailors would take all measures to ensure that the Congress of Soviets would be able “to continue its proceedings in peace.”[18]

This statement was greeted with a loud outburst of applause. As the handful of Mensheviks, Socialist-Revolutionaries, members of the bourgeois City Duma, and members of the Executive Committee of the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies were pushing their way to the exit, another group pushed their way into the hall. The chairman announced: “The Bolshevik members of the Duma have arrived to conquer or die side by side with the All-Russian Congress of Soviets.”[19] Down the gangway came the Bolshevik members of the Petrograd City Duma, accompanied by the ringing cheers of the delegates.

At 3:10 a.m., on October 26, the session of the Congress was resumed after a brief adjournment. The capture of the Winter Palace was announced. The last stronghold of the counter-revolution had fallen. The members of the Provisional Government, headed by the “dictator” Kishkin, had been arrested by the Red Guards and soldiers. The Provisional Government, which during its brief existence had deservedly earned the hatred of the masses of the people, was no more.

One after another messengers arrived with news of fresh victories achieved by the Great Proletarian Revolution and the passing of new units of the army to the side of the revolutionary people.

The Commissar of the garrison of Tsarskoye Selo reported:

“The garrison of Tsarskoye Selo is guarding the approaches to Petrograd. . . . When we heard that the Cycle Battalion was coming we prepared to offer resistance, but our alarm was uncalled for; it turned out that there were no enemies of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets among our comrades the cyclists. When we sent our Commissars to them we found that they, too, were in favour of a Soviet Government. . . . I declare that the garrison of Tsarskoye Selo stands for the All-Russian Congress and for the revolution, which we shall defend to the very last.”[20]

He was followed by the representative of the 3rd Cycle Battalion, which Sergo Orjonikidze had visited. The Congress greeted this soldier with loud cheers. He said:

“Until recently we were stationed on the South-Western Front. The other day we received telegraphic orders to move to the North. The telegram stated that we were going to protect Petrograd, but it did not say from whom. We seemed to be blind-folded, and we did not know where we were going. But we had a vague idea of what was in the wind. All the way we kept asking ourselves: Where? What for?

“At Peredolskaya Station we held a meeting with the 5th Cycle Battalion in order to clear up the situation. At this meeting we found that not a single man among us cyclists was willing to fight our brothers and spill their blood. . . . We decided not to obey the orders of the Provisional Government. We said that in that government there were people who were unwilling to protect our interests, but were sending us against our own brothers. I tell you definitely, we shall not put into power a government which is headed by capitalists and landlords.”[21]

When the speaker had finished it was reported that a telegram had been received stating that a Military Revolutionary Committee had been formed on the Northern Front “which will prevent the movement of troops against Petrograd.”[22]

The Congress sent greetings to the Military Revolutionary Committee of the Northern Front.

The Congress then adopted a manifesto “To the Workers, Soldiers and Peasants,” drawn up by Lenin, which stated:

“The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, at which the vast majority of the Soviets are represented, has begun. A number of delegates from the Peasants’ Soviets are also present. The mandate of the compromising Central Executive Committee has terminated.

“Backed by the will of the overwhelming majority of workers, soldiers and peasants, backed by the victorious insurrection of the workers and the garrison in Petrograd, the Congress takes power into its own hands.

“The Provisional Government has been overthrown and most of its members have been arrested. . . .

“The Congress decrees: all power in the localities shall pass to the Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, which must ensure genuine revolutionary order.”[23]

This brief manifesto, written in Lenin’s terse and concise style, ushered in a new era in the life of many millions of people. From that moment, the rule of the landlords and the capitalists in Russia was abolished forever, and the great mass of the working people were enlisted for the task of governing the country. Lenin’s manifesto concluded with the following revolutionary appeal on behalf of the Congress of Soviets to the soldiers, industrial workers and other working people calling upon them to be staunch and vigilant:

“Soldiers, actively resist Kerensky, the Kornilovite! Be on your guard!

“Railwaymen, hold up all troop trains dispatched by Kerensky against Petrograd!

“Soldiers, workers and employees, the fate of the revolution and the fate of the democratic peace lies in your hands!

“Long live the revolution!”[24]

This was the first time in history that the transfer of power from one class to another was decreed in such plain and brief terms.

The reading of this manifesto was frequently interrupted by loud applause from the delegates. The “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, who had remained at the Congress, supported the manifesto. At 5 a.m. it was adopted by the Congress with only two dissentients, with 12 abstaining.

Although it was already morning and the delegates were tired, all were as cheerful as could be; their eyes sparkled with youthful fire, and their hearts were filled with joy and hope. The first faint streaks of day glimmered in the October sky, heralding the dawn of a new era for the whole of mankind.

[1] Central Archives, The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, State Publishers, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, p. LIII, Editorial Note.

[2] “The Congress of Soviets,” Rabochy Put, No. 46, October 26, 1917.

[3] Central Archives, The Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, Moscow-Leningrad, 1928, p. 32.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., p. 33.

[6] Ibid., p. 34.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p. 35.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., p. 36.

[11] Ibid., p. 39.

[12] Ibid., p. 38.

[13] Ibid., p. 37.

[14] Ibid., p. 38.

[15] Ibid., pp. XXXV and XXXVI.

[16] Ibid., p. 41.

[17] Ibid., pp. 44-45.

[18] Ibid., p. 45.

[19] Ibid., p. 42.

[20] Ibid., pp. 49-50.

[21] Ibid., p. 50.

[22] Ibid., p. 52.

[23] Ibid., p. 53.

[24] Ibid., pp. 53-56.

Previous: The October Insurrection—A Classical Example of a Victorious Proletarian Insurrection

Next: The Decrees of the Great Proletarian Revolution