Before the revolution the Ukraine was the chief coal and metallurgical base of Russian industry, and Ukrainian agriculture provided millions of tons of wheat for the home and foreign market. Furthermore, the food processing industry was highly developed in the Ukraine.

During the imperialist war the Ukraine served as the supply base for the Russian armies on the South-Western and Rumanian Fronts, which were the main theatres of military operations in 1916 and 1917.

The Bolshevik Party was confronted with the all important task of preparing for the armed insurrection in the Ukraine, the success of which would facilitate the first steps taken by the proletarian dictatorship at the centre. This explains why the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party devoted so much attention to the Ukraine.

The Central Committee sent to the Donets Basin, in the Ukraine, K. E. Voroshilov, who had led the revolutionary struggle there in 1905.

The central Bolshevik newspapers assisted the Ukrainian Bolshevik press. The Kharkov newspaper Proletary was in constant communication with the Moscow Sotsial-Demokrat and regularly received instruction and copy from M. S. Olminsky, the editor of that paper.

The suppression of the Kornilov mutiny marked the turning point in the development of the revolution in the Ukraine.

The workers of Kharkov, Ekaterinoslav and Kiev and the miners of the Donets Basin demanded arms.

In connection with the Kornilov mutiny, the Kharkov Committee of the Bolshevik Party issued a manifesto to the workers calling upon them to arm.

“It is necessary immediately to arm the workers,” said the Committee in its manifesto. “No revolution has succeeded with the aid of words alone.

“The proletariat will take, and has already taken, the lead in defending the revolution. It is necessary immediately to arm the proletariat with the stocks of arms available in the city. Time does not wait. Long live the workers’ Red Guard.”[1]

Delegates were sent to Tula to procure arms.

The Bolsheviks were not daunted by the enormous difficulties that stood in the way of the mass arming of the workers. They took advantage of every opportunity that arose for doing so.

The combat groups armed themselves even with swords, and the workers forged their own bayonets for their rifles. Those who had firearms of any kind were regarded as lucky. The Red Guards had to take turns at firing practice, as there was only one rifle for every two men.

A big part in directing this work was played by K. E. Voroshilov.

At the time the February bourgeois-democratic revolution broke out Voroshilov was in Petrograd as a delegate from the Donets Basin. The Donets miners sent repeated requests to the Central Committee urging that Voroshilov be allowed to return. In view of the enormous importance of the Donets Basin for the revolution the Central Committee consented and Voroshilov returned to Lugansk. There, utilising his old connections, he built up a stronghold of Bolshevism long before the Kornilov mutiny. After the July events he organised a meeting of solidarity with the Petrograd proletariat. On a sweltering July day, columns of workers marched from all parts of the town to the Preobrazhensky Square, carrying banners bearing the inscriptions: “Down with the counter-revolution!” “Long live the power of the workers, peasants and soldiers!”

On the way to the square the demonstrators encountered a troop of Cossacks led by Colonel Katayev, the chief of the Lugansk garrison. Silently allowing the demonstration to pass, the Cossacks followed up in its rear. The meeting was opened in the square. As soon as a Bolshevik speaker stepped on to the platform the Cossacks, at a sign from Colonel Katayev, raised a frightful din. From the ranks of the Mensheviks, who kept close to the Cossacks for protection, voices were heard shouting:

“We’ve had enough of Bolshevik demagogy!”

The Bolshevik speaker was followed by the Uyezd Commissar of the Provisional Government, the Menshevik, Nesterov. A demagogue and slanderer, he managed, right up to June 1917, simultaneously to occupy the posts of Commissar of the Provisional Government, Chairman of the Committee of Public Safety and Chairman of the Soviet. Shortly before this demonstration, however, Nesterov had been expelled from the Soviet as a result of the campaign conducted by Voroshilov. Now, under the protection of the Cossacks, he tried to win the workers to his side. The workers, however, denied him a hearing. “Down with the traitor!”—they shouted, and amidst the howls and jeers of the demonstrators, this Menshevik was dragged from the platform.

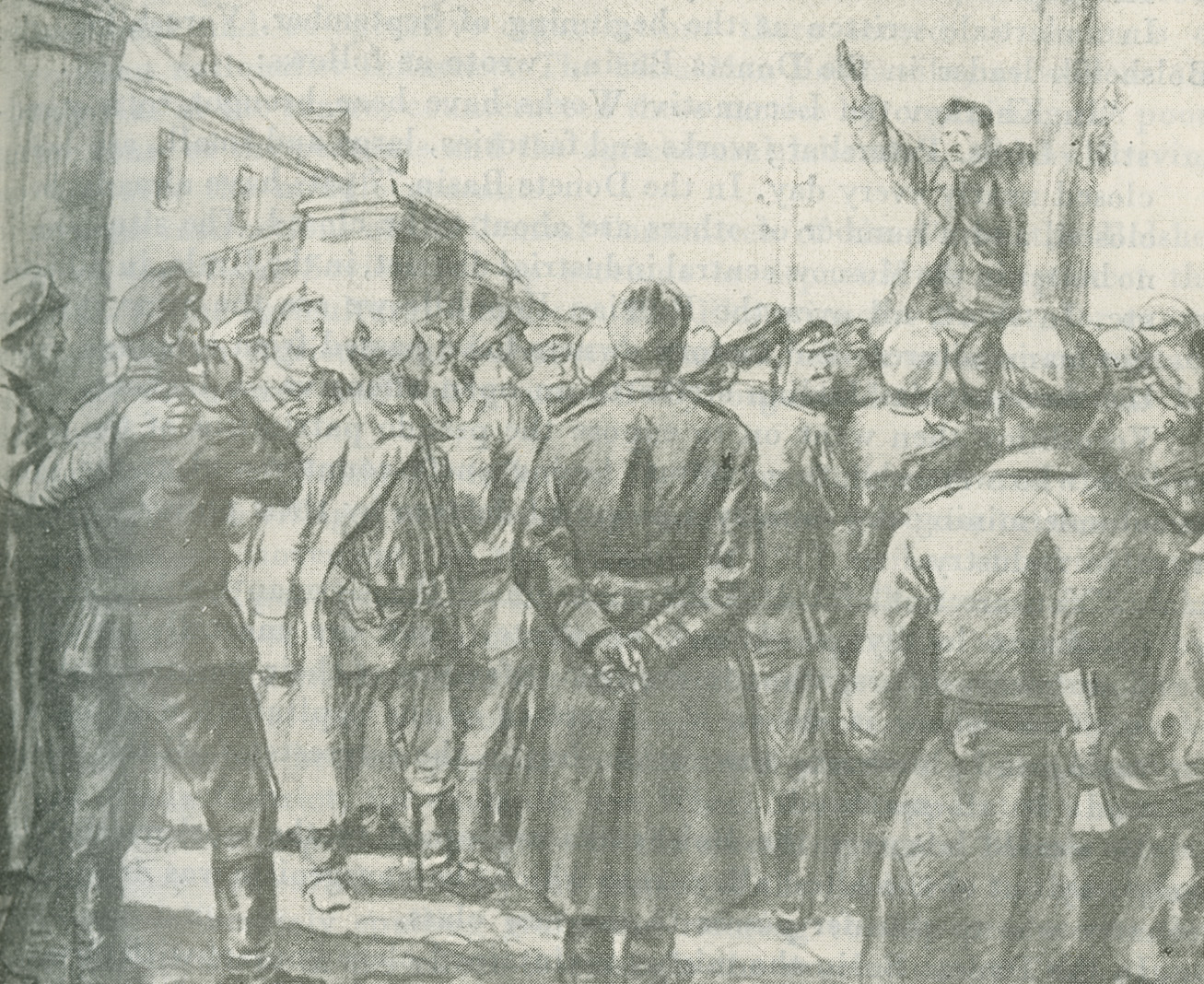

At last Voroshilov appeared on the platform. In his speech he fiercely denounced the Provisional Government and exposed the treacherous conduct of the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks during the July days. Again vicious cries were heard from the small crowd of Mensheviks. The Cossacks took up these cries and the din increased, drowning Voroshilov’s voice. Voroshilov then slowly descended from the platform and calmly directed his steps towards the crowd of Mensheviks and the Cossacks. He was followed by armed workers. Colonel Katayev’s command rang out: “Ready!”

The Cossacks drew their sabres, but they hesitated to attack Voroshilov. At this moment the ranks of the workers opened and a detachment of Bolshevik soldiers appeared with their rifles at the ready. Shouting “Long live the Soviets!” the soldiers resolutely advanced against the Cossacks. The latter turned their horses and galloped off, followed by the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries. The meeting was then resumed. Towards evening the workers and soldiers unanimously adopted a Bolshevik resolution demanding the transfer of all power to the Soviets.

In those days only vague rumours about the Kornilov mutiny had reached Lugansk. Voroshilov was tireless in his activities. On August 27 he addressed a soldiers’ meeting, and in the evening of the same day he organised a mass meeting of workers and soldiers. On August 28 he addressed a meeting of workers at the Hartman Works, at which he summed up the events of the past six months of the revolution.

“These events have shown,” he said, “that the Bolshevik Party is the only true party of the revolutionary proletariat and has correctly estimated the state of affairs in the country and the forces operating in our revolution.”[2]

When the first definite information about the Kornilov mutiny was received Voroshilov set up a Revolutionary Committee. That same night, on the orders of the Committee, the officers of the local garrison and the former high officials of the tsarist government were arrested. The Committee sent its Commissars to all the public offices for the purpose of ensuring the normal conduct of business and of stopping attempts at sabotage.

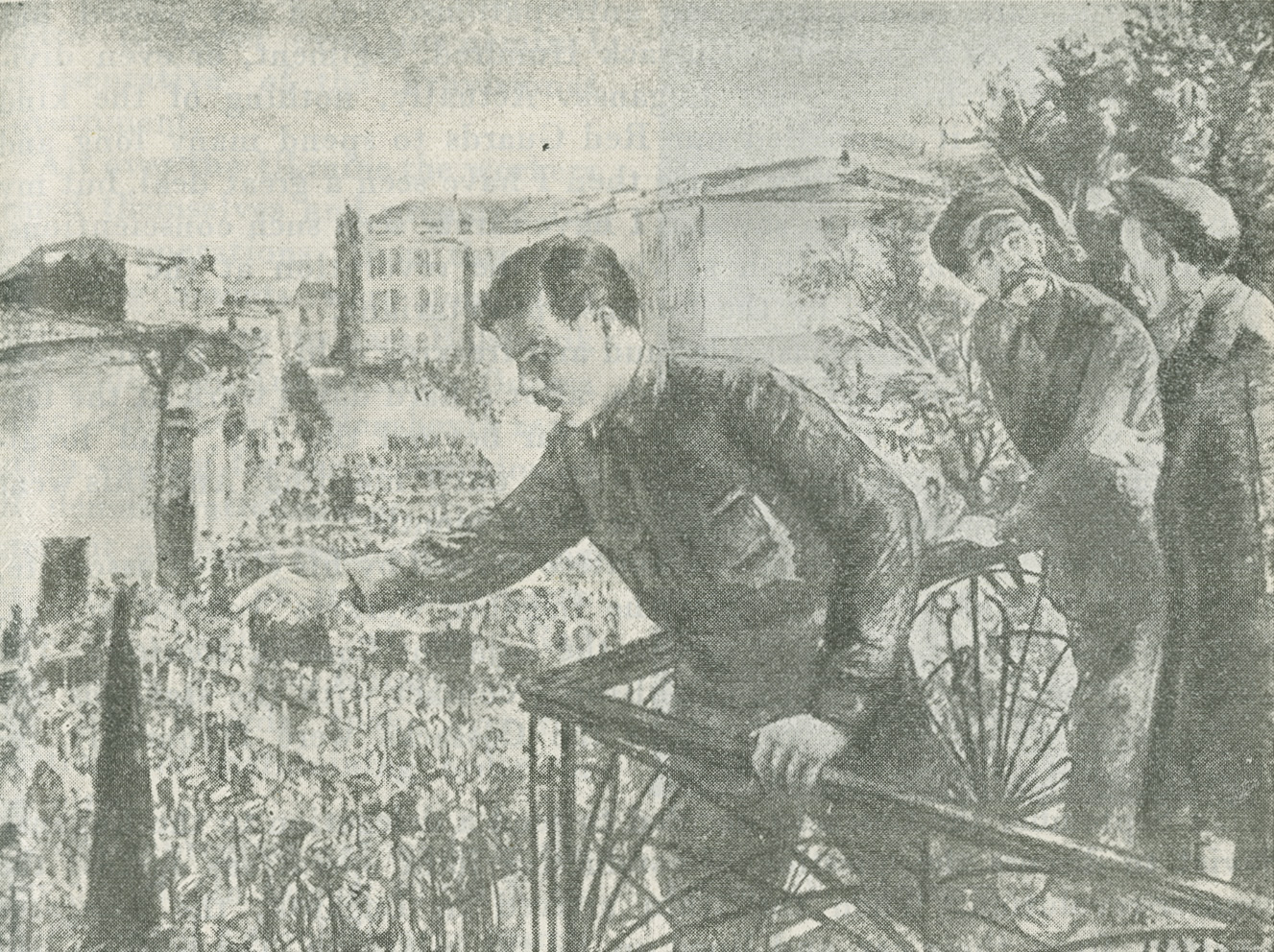

On August 30 meetings were held in all the units of the Lugansk garrison. The soldiers expressed their complete support of the Bolsheviks and their readiness to fight Kornilov. That day the units elected new commanders from among the rank and file. One of these newly elected commanders came to the People’s Palace, where the Bolshevik Party had its committee rooms, and informed Voroshilov that his men were lined up outside and desired to demonstrate their devotion to the revolution. The members of the committee went out on the balcony and the soldiers in serried ranks marched past the building responding to Voroshilov’s greetings with loud “Hurrahs!”

The fact that the garrison had been won over naturally had a profound effect upon the further development of the revolution in Lugansk. The workers armed themselves in order to repel the anticipated attack of the Don counter-revolution. As Voroshilov wrote in his reminiscences:

“Our proximity to the Don Region and the old hostility that had remained from the first revolution between Red Lugansk and the very black Don Region gave rise to a host of very absurd as well as to some grave rumours, assumptions and anticipations. Not a day passed but what, according to rumour, a Cossack Hundred, regiment, or even division, was marching against Lugansk. Actually, nothing of the kind happened, but it compelled our Red Guards to spend many long and trying hours on guard duty. Since then I have seen a great deal, but my conscience compels me to say that I have rarely seen such conscientious, self-sacrificing and unselfish service to the revolution at the fighting post as was performed by the Lugansk proletarians.

“In pouring rain, impassable mud and freezing cold, in the darkness of the night, groups of Red Guards, after a hard day’s work at the factory, would march into the steppe, far beyond the city, and loyally guard all the approaches to the city until morning. And this went on not for one day, or two, but for whole months.”[3]

Voroshilov formed a Defence Committee headed by his closest associate, A. Y. Parkhomenko, the leader of the Lugansk workers’ combat groups. Scouts and agitators were sent out to the adjacent Cossack stanitsas. The Lugansk Soviet succeeded in establishing contact with the stanitsas Mityakinskaya and Luganskaya, where the Cossacks were favourably inclined towards the Bolsheviks.

In September the Cossacks decided to send a delegation to the Lugansk Soviet to discuss the question of conducting joint operations against the counter-revolution. When the train arrived in Lugansk, the delegates emerged from their car and lined up on the platform. The workers had not been warned of the arrival of the delegation, and being hostile towards Cossacks in general, they surrounded the visitors and demanded that they should remove their epaulets, which to them were the symbols of the tsarist regime. The delegates pleaded with the workers not to insist on this as they had to wear these epaulets in order to be able to influence the rest of the Cossacks. The misunderstanding was cleared up and a friendly conversation ensued between the Lugansk workers and the delegates from the Cossack stanitsas.

Soon permanent contacts were established between Lugansk and the surrounding stanitsas. The local counter-revolutionary forces gradually began to concentrate in Novocherkassk.

The situation in the city on the eve of the October battles is most vividly described in a report sent from Lugansk to the Central Committee of the Party at the end of September which stated:

“All the organisations in the city are in our hands. The Mayor of the City, the members of the Municipality, the Chairman of the City Duma, the Soviet of Deputies, the trade unions and the newspapers are all ours.”[4]

Thus the Bolsheviks in Lugansk prepared to seize power. The city was practically under the control of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, of which Voroshilov was the head. The representative of the Provisional Government was merely the nominal authority. The Lugansk workers were only waiting for the signal from the centre to expel even this nominal representative of the Provisional Government.

All over the Ukraine the workers armed themselves and prepared for decisive operations. Even the compromising Soviets were compelled by mass pressure to pass Bolshevik resolutions. On August 25 the Odessa Soviet still passed a Menshevik resolution calling for the prohibition of all demonstrations; but five days later, it passed a resolution calling for the arming of the Red Guards and the payment of the Red Guardsmen by the factory owners. The Red Guards took over the function of maintaining order in the city.

Similar progress was made in the Kiev Soviet. On August 30 the Kiev Soviet passed a resolution to search for and requisition arms for the purpose of equipping the combat groups. At the same meeting a resolution was passed to disarm the Polish fighting squads formed in Kiev by the Polish counter-revolutionary organisations.

When the Provisional Government tried to disarm the workers after the suppression of the Kornilov mutiny, it met with mass resistance which had been organised by the Bolsheviks. P. P. Dobroselsky, the Kharkov Gubernia Commissar of the Provisional Government, acting on Kerensky’s orders, wanted to dissolve the Revolutionary Committees which had been set up at the time of the Kornilov mutiny, but he failed. At a meeting of the Kharkov Soviet, Kerensky’s Commissar was opposed by N. Rudnyev, the commander of a company of the 30th Regiment, and one of the leaders of the Kharkov military organisation of the Party and of the Red Guard. Rudnyev succeeded in transforming the 30th Regiment into a Bolshevik stronghold. The soldiers of this regiment said: “We are all Bolsheviks.” Nikolai Rudnyev died like a hero fighting the Whiteguard Cossacks near Tsaritsyn in 1918.

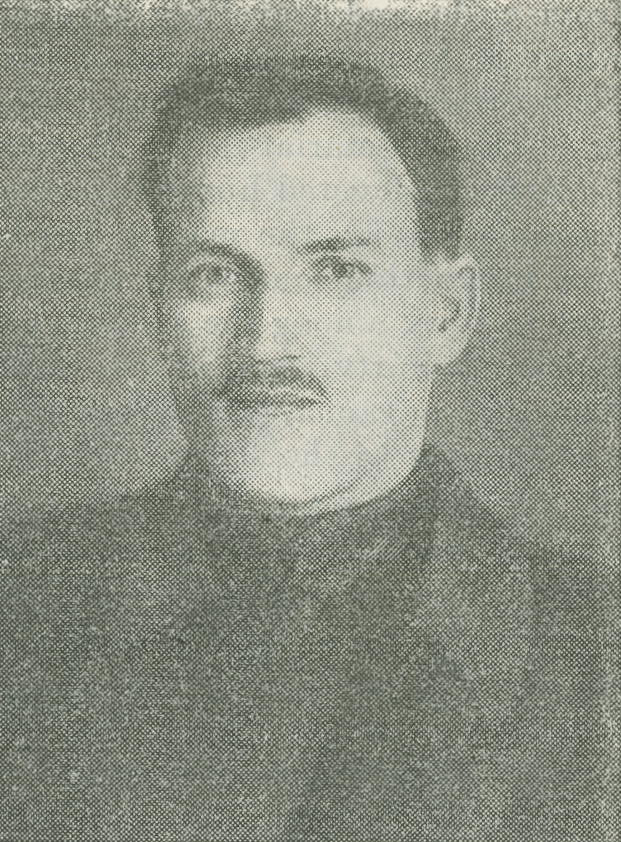

One of the most active in exposing the compromisers was Artyom (F. A. Sergeyev). He was well known among the workers in the Donets Basin as an eloquent speaker and leader of the Bolshevik organisations in the turbulent days of 1905. After the defeat of the first revolution Artyom was arrested and imprisoned, and then sent into exile. In 1910 he escaped from exile and travelling through China and Japan went to Australia, where he became prominent in the revolutionary working-class movement. He returned to Russia in May 1917 and at once became the recognised leader of the proletariat in the Donets Basin.

Artyom devoted himself particularly to the work of agitation and propaganda among the masses. On his initiative the Kharkov Soviet organised instruction courses for speakers who, after finishing the course, were sent to work among the soldiers and peasants. The leading members of the Bolshevik Party, men at the head of large organisations, personally conducted propaganda, setting examples of how the workers and soldiers should be won over to the side of the revolution.

At the end of August 1917 Artyom, accompanied by a group of comrades, came to the 6th Artillery Depot, which was part of the Kharkov garrison, where a meeting of the soldiers was to be held. The officers, however, refused to permit Artyom to enter the depot, but this did not daunt him. He posted himself in the street outside the barrack yard and began to read aloud a popular Bolshevik pamphlet, making a running comment on what he read. A large crowd gathered. Attracted by Artyom’s speech, the soldiers in the barrack yard pushed their officers aside and coming out into the street listened to Artyom with close interest and then took an enthusiastic part in the meeting which ended in the adoption of a Bolshevik resolution.

The Bolshevik organisation among the Kharkov railwaymen, which was headed by Artyom, made a practice of sending out groups of their members to hold impromptu open air meetings. Carrying a banner and a portable platform, a group would stop at a busy street corner and hold a short meeting, and when that had finished they would go on to the next street corner.

At a meeting of the Kharkov Soviet held on September 12, the slogans of the political demonstration that had been fixed for September 14 were discussed. Artyom called upon the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik majority of the Soviet to support the slogans “All power to the Soviets!” and “All the land to the working peasants, at once and without compensation.” The Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary, Odoyevsky, opposed this and proposed instead that the Soviets’ first slogan should be “All power to revolutionary democracy.” As for the second, he proposed that it should be dropped altogether on the ground that “the land must be transferred to the peasants in an organised manner, and this could not be done at once.”[5]

The slogan proposed by the Bolsheviks for the immediate transfer of the land to the peasants without compensation was rejected by the Socialist-Revolutionaries who predominated in the Soviet.

The Bolsheviks would not admit defeat, however. Artyom stood up and addressing the Presidium angrily said:

“I request that it be recorded in the minutes that for three hours the Soviet discussed the question as to whom the land should belong—the landlords or the peasants—and at last decided that it should belong to. . .the landlords.”[6]

This stinging statement was greeted with loud applause. That day the Bolsheviks polled nearly half the votes in the Soviet. The influence of the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks began to wane.

The demonstration which was held in Kharkov two days later was conducted under Bolshevik slogans, and the meeting that followed was addressed only by Bolshevik speakers. This demonstration showed that the influence of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik Soviet among the masses had been greatly shaken.

By their persevering and self-sacrificing efforts among the proletarian masses of the Ukrainian towns, the Bolsheviks won over the majority of the working class.

The capitalists retaliated by shutting down factories.

In an article written at the beginning of September, Voroshilov, the Bolshevik leader in the Donets Basin, wrote as follows:

“In Kharkov the Locomotive Works have been brought to a standstill. In St. Petersburg works and factories, large and small, are being closed nearly every day. In the Donets Basin 77 pits have already been closed, and a number of others are about to be closed. The situation is no better in the Moscow central industrial district, in the Urals, in Siberia, etc. In short, all over the Russian Republic we see the same thing—the manufacturers and factory owners have passed from sabotage, from the surreptitious Italian strike to an open offensive—a lockout.”[7]

Voroshilov then went on to expose the pseudo patriotism of the bourgeoisie who were shouting about loving one’s country and at the same time undermining the country’s power of defence by their policy of sabotage in industry.

“You are not afraid of the invasion of the German hordes, as your henchmen loudly proclaim,” he wrote, “you are mortally afraid of your own workers, who are the true defenders of their country, but who want to defend it not in the interests of the capitalists who are torturing and plundering the nation, but in the interests of all the toilers and of all mankind. . . .”[8]

In simple language the Bolsheviks explained to the workers that the only way out of the blind alley into which the bourgeoisie was driving the country was to transfer power to the new class.

In the Donets Basin the miners maintained close contact with the peasants of the surrounding villages. The miners used to hold their celebrations in these villages and often arranged their wedding festivities there. They informed the peasants of the political events that were taking place and explained their significance.

After the February Revolution the Bolsheviks took advantage of these traditional ties to strengthen their influence in the rural districts. Under their direction Village Soviets were formed in the Donets Basin. As a result the peasants in villages like Shcherbinovka, Nelenovtsi, Zaliznoye and others, opposed the local Socialist-Revolutionaries. The influence of the Lugansk Uyezd Bureau of the Soviet of Workers’, Peasants’ and Soldiers’ Deputies extended far beyond the Lugansk District. This Bureau was presided over by Voroshilov. It organised “excursions”—on foot, owing to lack of funds—of worker delegates of the Lugansk Soviet to the surrounding villages where they acted as arbitrators in disputes over the renting and parcelling out of land and explained to the peasants the Bolshevik program on the land and peace questions.

All over the Ukraine the peasant movement developed under Bolshevik leadership. The Ukrainian countryside was distinguished for its extensive development of capitalist relations and for its large class of agricultural labourers. With the aid of the kulaks the Ukrainian nationalists tried to set up their own organisations in the rural districts, and the various educational and co-operative organisations there served as channels of Ukrainian nationalist influence. The Ukrainian Bolsheviks, as well as the Bolsheviks at the centre, counteracted these tactics by organising the poorer sections of the peasants and the agricultural labourers, and by striving to win over the middle peasants.

On the instructions of the Central Committee of the Party the Bolsheviks in the local Soviets set up sections or departments to protect the interests of the agricultural labourers. The Ekaterinoslav Soviet, for example, set up an Agricultural Labourer’s Bureau, which maintained contact with all the uyezds and fairly successfully organised the agricultural labourers.

The growth of Bolshevik influence in the rural districts and the close proximity of the villages to the working-class centres gave rise to new forms of the peasant movement. In the autumn of 1917 strikes of agricultural labourers and of poor peasants who worked for the landlords and the kulaks broke out all over the Ukraine. These were undoubtedly stimulated by the growing strike movement in the industrial centres of the country. Even the demand for workers’ control of industry, which was a specifically working-class demand, became popular in the rural districts of the Ukraine. In the Uman District, for example, the Rural Soviet appointed a special commissioner to inspect the progress of the threshing on the Talnov estate. This measure was called forth by the tactics of the landlords in this region who were deliberately spoiling grain and refusing to ship produce to the industrial districts in the effort to strangle the revolution by “the gaunt hand of famine” as had been advised by the millionaire Ryabushinsky.

The representatives of the bourgeoisie and the landlords, and their mercenary newspaper hacks, raised a howl about the alleged disorder and anarchy in the rural districts, but in their secret dispatches the representatives of the Provisional Government were obliged to admit that by their propaganda the Bolsheviks were establishing revolutionary order and organisation. Thus, the Uyezd Commissar of the Provisional Government in Berdichev in a report to the authorities in Kiev dated October 16, stated:

“On one of the estates belonging to Tereshchenko, the peasants, according to the statement of the steward, carted off about 10,000 poods of straw which had been set aside for the army, under absolutely exceptional circumstances, namely: the peasants committed this act quite deliberately, conscious of their rights, on the grounds that everything now belonged to the people. First they seized the straw, then the farm implements, the land . . . i.e., they carried out their intentions systematically, without the usual disorders and conflicts. “This phenomenon,” wrote the Uyezd Commissar in conclusion, “is undoubtedly the result of Bolshevik propaganda carried into the rural districts almost exclusively by soldiers.”

The poorer sections of the peasantry began to understand the general political aims of the revolution. In their resolution the peasants not only demanded the settlement of the questions of land tenure and rents, the abolition of landlordism and the cessation of the war, but also the dissolution of the State Duma and the Council of State, and the prosecution of Kornilov and his accomplices. In a resolution adopted at the end of September, the Kherson Gubernia Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies demanded the immediate convocation of the Second Congress of Soviets, the right of self-determination for the different nationalities in Russia, and workers’ control of production and distribution. The peasant insurrection in the Ukraine proceeded under Bolshevik slogans, but the special conditions prevailing in the Ukraine and the existence of powerful nationalist organisations limited its scope and force. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks incited the Ukrainian peasants against the workers, and against the representatives of Russian democracy generally.

At a meeting of the Lubny Soviet, the Ukrainian nationalist, Sukhenko, claiming to act in conformity with the instructions of the Central Rada, strongly objected to the dispatch of grain to Moscow and Petrograd. The nationalists operated hand in hand with Ryabushinsky in trying to starve the revolution. The Russian counter-revolutionaries, in their turn, made extensive use of the Ukrainian nationalist organisations. At a congress of instructors of village co-operative societies in the Poltava Gubernia, the Ukrainian Socialist-Revolutionary, Bagri, was compelled to admit that Black Hundreds belonged to the Socialist-Revolutionary organisation and that one of them was the former head of the City Duma. This Black Hundred agent was actually re-elected to this post with the aid of the Socialist-Revolutionaries.

The peasant insurrection in the Ukraine was supported by the movement in the army.

In the beginning of October Lieutenant-Colonel Bogayevsky of the Headquarters Staff of the Commander of the South-Western Front drew up a memorandum on the revolutionary movement in the army in which he vividly described how much the officers feared the rank and file. The soldiers are everywhere and always dangerous, he wrote; everywhere and always they cause disorder. Whenever they are quartered at a particular place for any length of time they take the lead of the peasant movement. When on the march they wreck the landlords’ mansions. When they are transported by rail they enter into communication with the revolutionary railwaymen.

All attempts to suppress the insurrection in the army by armed force failed. As was stated in this memorandum:

“. . . every attempt on the part of the officers to restore order is met with forcible resistance, accompanied by the charge that the officers want to restore the old regime and are serving the interests of the bourgeoisie and landlords.”[9]

The author of the memorandum recommended two methods of combating the revolution: 1. surgical, “i.e., punitive,” and 2. sanitary, “i.e., preventative,” but he at once added the following melancholy observation:

“Under present conditions, however, as is evident from reports received, the surgical measures are often nullified by the temporary bluntness of the government’s surgical instruments.”[10]

The counter-revolutionaries were still deluding themselves with the hope that the “instruments” were only temporarily blunted. While fighting to arm the workers, the Ukrainian Bolsheviks made vigorous preparations for the Second Congress of Soviets.

On October 6, the Regional Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies of the Donets and Krivoy Rog Basins was opened in Kharkov. The Congress was attended by 146 delegates, of whom 49 were Bolsheviks, 44 Mensheviks, 42 Socialist-Revolutionaries and two Anarchists.

When the agenda was discussed the representative of the Bolshevik group proposed that the report on the conditions of the proletariat in the Donets Basin be heard before the report of the Regional Committee.

The Bolsheviks’ denunciation of the activities of the compromisers on the Regional Committee before the report of the Committee was heard caused consternation in the Presidium. True, the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks had a majority at the Congress, but the Congress was obviously packed. All the members of the Regional Committee and of the District Committees, the overwhelming majority of whom were Mensheviks, were present with the right to speak and vote. But even then the compromisers were not sure of their position.

When the report of the Regional Committee was discussed the Bolsheviks subjected it to a withering criticism.

In an eloquent speech Artyom revealed the true role the Mensheviks were playing on the Regional Committee.

“I criticise the Regional Committee not for its inactivity, but for its activities against the working class,” he said. “The Committee merely served as an office of the Ministry of Labour. It sent its representatives to various bodies in order to arrange a compromise. The Committee hindered the workers’ efforts to organise. This was the case in Debaltsevo and in other districts of the Donets Basin.”

“The Regional Committee was not a workers’ organisation, but a lash for the workers,”[11] declared Artyom amidst the loud approval of the majority of the Congress.

Even the rank-and-file delegates of the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik groups listened to the Bolsheviks’ speeches with un-concealed sympathy.

The Congress ended with a formal victory for the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks, but the victors left the hall in a depressed mood. They had failed to carry out a single instruction issued by the compromising All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets and by their respective parties. Nor did they succeed in inducing the Congress to drop the demand for the convocation of the Second Congress of Soviets. They also failed to secure support for the new Provisional Government that was formed after the Democratic Conference.

On October 17 a Regional Conference of Soviets of the South-Western Territory was held in Kiev at which 34 Soviets were represented. Notwithstanding the strong opposition of the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks a Bolshevik resolution was adopted demanding the transfer of all power to the Soviets.

On the eve of the October Revolution the nationalist counter-revolutionaries in the Ukraine endeavoured to reach an agreement with the Provisional Government. As if in retaliation to the preparations for the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets, the Central Rada made arrangements for holding the Third All-Ukrainian Army Congress in Kiev on October 20. This was a congress of representatives of Ukrainian army formations. A congress of representatives of Cossacks at the front was to be held in Kiev on the same day. The counter-revolutionaries intended these two congresses to serve as political centres of the fight against the Bolsheviks as well as military centres, for the 2,000 armed soldiers and Cossacks who would be assembled could serve as the nucleus of a counter-revolutionary force.

The All-Ukrainian Army Congress was attended by 940 delegates, most of them soldiers from the front. About 800 of these belonged to Ukrainian nationalist parties. But even this did not inspire the Central Rada with confidence that it would obtain the support of the soldiers at the front, for the temper of the rank-and-file delegates was obviously revolutionary. They would not hear a word about reaching an agreement with the Provisional Government.

In the middle of October the Soviets in the Ukraine elected their delegates to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets. The elections were the occasion of a fierce struggle between the Bolsheviks on the one hand and the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks on the other.

Meanwhile, the compromising All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets did all in its power to put off the convocation of the Congress.

The Central Executive Committee’s telegram instructing the Soviets to elect delegates to the Second Congress was received in Kiev only on October 19. The Kiev Soviet elected its delegates that very day. Of the 13 delegates representing the various Kiev organisations (the City, Area and Regional Soviets) seven were Bolsheviks, three Ukrainian Social-Democrats and three Internationalist Socialist-Revolutionaries.

The Odessa Soviet elected its delegates to the Congress at a meeting held on October 10. While the meeting was in progress a collision occurred in the streets between the Haidamaks and the Red Guards, in which the former tried to disarm the latter. The terrified Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks proposed that the Chevaliers of St. George be called out to guard the city and that the Cossacks be sent for. Towards the end of the meeting, however, it was learned that the Red Guards had dispersed the Haidamaks and that order had been restored. The Soviet passed a resolution urging the necessity of further arming the workers. The election of delegates to the Second Congress was postponed to the following day.

On October 11, at a joint meeting of the Odessa Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’, Peasants’ and Sailors’ Deputies, the discussion on the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets was resumed. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks changed their tactics again, the second time in 24 hours. Convinced that they would be unable to sabotage the Congress, they now formed a united front in support of the demand for the formation of a “homogeneous Socialist government.” In this united front of petty-bourgeois parties, both the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks united around the Internationalist Socialist-Revolutionaries whose “radicalism” was to serve as a screen for the compromising tactics of the entire bloc. This “Left” manoeuvre failed, however. The resolution proposed by the Bolsheviks polled 306 votes, while that of the Internationalist Socialist-Revolutionaries, which called for the formation of a “homogeneous revolutionary democratic government,” polled 169 votes. No other resolution was submitted.

The Odessa Soviet delegated to the Congress five Bolsheviks, two Socialist-Revolutionaries and one Internationalist Menshevik.

Of the 83 delegates chosen by the Soviets of the Ukraine for the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets 40 belonged to the Bolshevik Party. A considerable number of the delegates belonged to Ukrainian petty-bourgeois parties, but their constituents gave them a definite mandate to defend the power of the Soviets.

Of the 40 Ukrainian Soviets represented at the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets only five had supported the slogan “All power to democracy!” which the Socialist-Revolutionary and Menshevik agents of the bourgeoisie flaunted at that time. These Soviets had long ago lost contact with the masses and had not stood for election since the beginning of the February Revolution. Such was the case with the Regional Committee of Soviets of the Donets and Krivoy Rog Basins. It had nothing in common with the Soviets in the districts, which had unanimously instructed their delegates to the Second Congress to fight for the transfer of power to the Soviets.

The Ukrainian masses marched forward to meet the proletarian revolution under the banner of the Bolsheviks.

[1] Leading article in Proletary (The Proletarian), Kharkov, special evening edition, No. 1, August 29, 1917.

[2] “The Hartman Works,” Donetsky Proletary (The Don Proletarian), Lugansk, No. 65, August 31, 1917.

[3] K. Voroshilov, “From the Recent, Infinitely Remote Past,” October 1917, State Publishers, Rostov-on-Don, 1921, pp. 65-66.

[4] “Party Life” (Excerpts from Letters to the Central Committee), Rabochy Put, No. 13, September 17, 1917.

[5] “The Meeting of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies of September 12, Proletary, Kharkov, No. 129, September 14, 1917.

[6] Ibid.

[7] K. Voroshilov, “Raining Blows,” Donetsky Proletary, Lugansk, No. 58, August 22, 1917.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Materials of the Secretariat of the Head Editorial Board of The History of the Civil War, Fund of Vol. II of “H.C.W.”

[10] Ibid.

[11] Central Archives of the Revolution, Kharkov, 353/C.94, folio 2.

Previous: The Difficulties of the Struggle to Transfer Power to the Soviets in the National and Border Regions

Next: In the North Caucasus