The Russian counter-revolutionary capitalists and landlords intended to muster their forces in Siberia, where the foreign imperialists could come to their aid. Siberia was one of the main sources of food supply for Central Russia. It was natural, therefore, that in their plans the Central Committee of the Party should attach great importance to Siberia.

It was no easy matter to conduct activities here. After the February Revolution the best forces of the Bolsheviks, who had been exiled to Siberia by the tsarist government, were recalled to Petrograd and other centres. Only local forces were available, and these had to be reinforced and rallied around the line of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party.

On March 20, 1917, J. M. Sverdlov stopped at Krasnoyarsk on his way back to European Russia from Yeniseisk, whither he had been exiled. Here he met the local Bolsheviks and outlined a plan for uniting all the Bolshevik forces in the district, and later on throughout Siberia. This plan was adopted and it was decided to set up a District Bureau of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.) to direct Bolshevik work in the district.

In the beginning of April a conference was held of the Bolshevik groups in Krasnoyarsk, Achinsk, Kansk and Yeniseisk. This conference instructed the Krasnoyarsk District Bureau to establish communication with all the Bolsheviks in Siberia. The conference sent greetings to the Central Committee of the Party and informed it of its organising activities. On April 13 a reply was received, signed by E. D. Stassova, stating:

“We welcome your new undertaking and endorse the formation of a Bureau. . . .”

In May the Krasnoyarsk Bolsheviks withdrew from the united Social-Democratic organisation. In July the Internationalist Social-Democrats followed suit and joined the Bolsheviks.

The Krasnoyarsk Bolsheviks exercised considerable influence among the local proletariat. The Sibirskaya Pravda, the only Bolshevik organ in the whole territory, was published in this town, and the Krasnoyarsky Rabochy, the organ of the Soviet, was under Bolshevik influence. The Bolsheviks had 180 members in the Soviet; the Mensheviks had two or three and the Socialist-Revolutionaries about 40.

In August the Central Siberian Regional Conference of the Bolshevik Party, representing about 5,000 members, was held in Krasnoyarsk. The Conference sent greetings to the Sixth Congress of the Party.

A Central Siberian Regional Bureau was set up to direct all Party activity in Siberia. This Bureau received an urgent instruction from the Central Committee to see to it that the Bolsheviks in Tomsk, Barnaul, Novonikolayevsk and Omsk withdrew from the united Social-Democratic organisations.

After the Regional Party Conference the Krasnoyarsk Bolsheviks toured Siberia, speaking at workers’ and Party meetings and forming new Party organisations.

One of the most active of the Krasnoyarsk Bolsheviks to leave for the working-class districts in Western Siberia was Y. E. Bograd.

Tomsk was one of the first united Social-Democratic organisations in Western Siberia to split. On September 1, as soon as the details of the Kornilov mutiny became known, a general meeting of the Tomsk Social-Democratic organisation was held at which a resolution was passed calling for the immediate transfer of power to the Soviets.

Next day a joint meeting of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and the Central Bureau of Trade Unions demanded the transfer of power to revolutionary democracy represented by the Soviets.

In the large garrison of Tomsk meetings of soldiers were held which were addressed by Bolsheviks and their sympathisers. At nearly all the meetings the soldiers passed resolutions containing the demand for “the transfer of all power to the Central Congress of Soldiers’, Workers’ and Peasants’ Deputies.”

At a meeting of the Social-Democratic organisation held on September 6 a report was delivered on the Regional Conference which had been held in Krasnoyarsk. After a heated debate a resolution was passed by 58 votes against nine with nine abstentions, stating that:

“. . . this meeting associates itself with the decision of the Conference [Central Siberian—Ed.] to join the R.S.D.L.P. (Bolsheviks) and declares that the decisions of Party Congresses and leading bodies are binding on the members of the organisation who remain in it after the adoption of the present resolution.”[1]

On September 9 a Gubernia Conference of the Bolshevik Party was held in Tomsk.

The delegates from the Sudzhenka and Anzherka mines, from Kemerovo, and those from Taiga Station, reported that Bolshevik influence had greatly increased among the masses and that the workers unreservedly adopted the slogan “All power to the Soviets!”

The Conference sent the following telegram to the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party and to the central Party organ:

“On behalf of 2,500 workers organised in the Party, the Tomsk Gubernia Conference has resolved to recognise the Central Committee as its Party Centre and its directions as binding. We are confident of the speedy return to the victorious proletariat of its honest and devoted leaders—Comrade Lenin and the others.”[2]

Several days after this Gubernia Conference a split took place in the Novonikolayevsk Party organisation. By a vote of 85 against 22 the meeting decided to associate itself with the platform of the Bolsheviks.

The break with the Unionists raised Bolshevik prestige in the Tomsk Gubernia. This was strikingly demonstrated at the Gubernia Congress of Soviets of Peasants’ Deputies which opened in the city of Tomsk in the middle of September and was attended by about 200 delegates. The Congress was dominated by the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries, but during the course of the proceedings, however, the leadership passed into the hands of the Internationalist Socialist-Revolutionaries and the Bolsheviks.

The report on the current situation was made by the Internationalist Socialist-Revolutionary, Lisiyenko, who was followed by N. N. Yakovlev, a Bolshevik, and one of the outstanding fighters for the dictatorship of the proletariat in Siberia.

N. N. Yakovlev joined the Bolshevik Party in 1905, while still a student at the Moscow University. His revolutionary work was frequently interrupted by arrests, imprisonment, exile in the Arctic Region, and exile abroad. He escaped from Siberia several times. While abroad he spent a year working in a brass foundry where he learned the trade of a foundryman.

In 1916 he was called up for military service. On the outbreak of the revolution he was elected to the Presidium of the Tomsk Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies. In 1918 he was shot by Kolchak forces.

Yakovlev’s speech at the Congress of Peasants’ Deputies in Tomsk had a powerful effect, and when he finished speaking he was greeted with loud and prolonged applause.

The resolutions proposed by the Bolsheviks and Internationalist Socialist-Revolutionaries differed on one point, namely, the agrarian question. The Socialist-Revolutionary resolution was adopted, but the Bolshevik resolution received as many as 60 votes.

The Tomsk Bolsheviks gained further successes at the joint meeting of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies and Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies. Here, too, Yakovlev spoke on the current situation. The meeting decided to unite the two Soviets and form a Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies. In their resolution, the Soviets insisted “on the immediate convocation of a Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies for the purpose of electing a new Central Executive Committee and of drawing up revolutionary tactics. . . .”[3]

At a meeting held on October 7 a Presidium of the united Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies was formed of which N. N. Yakovlev was elected chairman. At the same meeting two Bolsheviks were elected as delegates to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

The elections to the Tomsk City Duma, which were held on October 1, revealed to what extent Bolshevik influence had increased. The Bolsheviks won the largest number of seats, namely 34; the Socialist-Revolutionaries won 24 seats and the Mensheviks only six.

In Omsk the united organisation held together longer than in any other part of Siberia. The Omsk Bolsheviks carried on work mainly among the railwaymen, metal-workers and the soldiers of the garrison. One of the most outstanding Bolshevik agitators in Omsk, the 19-year-old Z. Lobkov, exercised enormous influence among the workers and soldiers; his influence was also felt in the work of the Omsk Soviet. His young and ardent life was cut short in May 1919, when he was arrested in Chelyabinsk as a member of the underground Bolshevik organisation and tortured to death by the Kolchak secret police.

On September 16 the Omsk Soviet passed a resolution demanding the immediate convocation of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets. At the same meeting a decision to form a workers’ Red Guard was adopted.

The Bolsheviks had raised the question of arming the workers as far back as May at a general meeting of the Social-Democratic organisation. But the Mensheviks had opposed this and had described the proposal to arm the workers as “an echo of the Leninist-Blanquist trends.”[4] Despite this opposition, however, the Bolsheviks began to organise combat groups.

Units of workers and peasants began to be formed and were trained by soldiers returned from the front. One of the organisers of such groups was Lobkov.

On October 12 a general meeting of the Omsk united Social-Democratic organisation was held at which 366 members were present. An Internationalist Menshevik presided. The question under discussion was the election of the Constituent Assembly, but this was linked up with the question as to which party centre the Omsk organisation was to submit to—the Bolshevik or the Menshevik.

The Bolsheviks proposed that the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party should be acknowledged as the leading centre. This proposal received 256 votes. A split followed.

The chairman of the meeting resigned and left the hall, followed by the Internationalist Mensheviks. The new chairman of this now exclusively Bolshevik meeting was Lobkov. The meeting decided to put up an independent Bolshevik ticket in the Constituent Assembly elections.

Almost at the same time the Bolsheviks in Irkutsk—the centre of Eastern Siberia—withdrew from the united organisation, membership of which hampered their efforts to extend their influence to the large local garrison. The Soviet of Workers’ Deputies and Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies existed separately. Lacking proletarian guidance, the soldiers drifted along in their own way.

The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party sent a representative to Irkutsk with the special mission of helping the Irkutsk Bolsheviks to set up their own organisation and of uniting the Workers’ and Soldiers’ Soviets.

As was the case in Omsk, the split in the Social-Democratic organisation came about in connection with the nomination of candidates for the Constituent Assembly. On the insistence of N. A. Gavrilov the Bolsheviks decided to put up their own ticket.

Nikolai Andreyevich Gavrilov came from a peasant family and was a school teacher by profession. In 1906 he was arrested while trying to smuggle revolutionary literature into his district. From then on his career was marked by imprisonment, penal servitude and exile in the Irkutsk Gubernia.

After the revolution he joined the Irkutsk united organisation of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party. In 1919 he was beaten to death by counter-revolutionaries.

At a meeting of the Gubernia Committee of the Social-Democratic organisation held in Irkutsk on October 4, Comrade Gavrilov demanded that a larger number of Bolsheviks be included in the list of candidates for the Constituent Assembly on the grounds that the Bolsheviks exercised greater influence in the city.

The Gubernia Committee refused to comply with this demand and denounced the statements by Gavrilov and other Bolsheviks as “disruptive” and unauthorised.

This dispute led to a split in the Irkutsk Social-Democratic organisation, from which the Bolsheviks withdrew.

Just at this time a group of Bolsheviks arrived from Krasnoyarsk.

On October 19 the first issue of the Bolshevik journal Rabochaya Sibir was published.

The Irkutsk City Committee of the Bolshevik Party, in conjunction with the comrades who had arrived from Krasnoyarsk, drew up plans for forming a military organisation and for securing new elections to the Soviets.

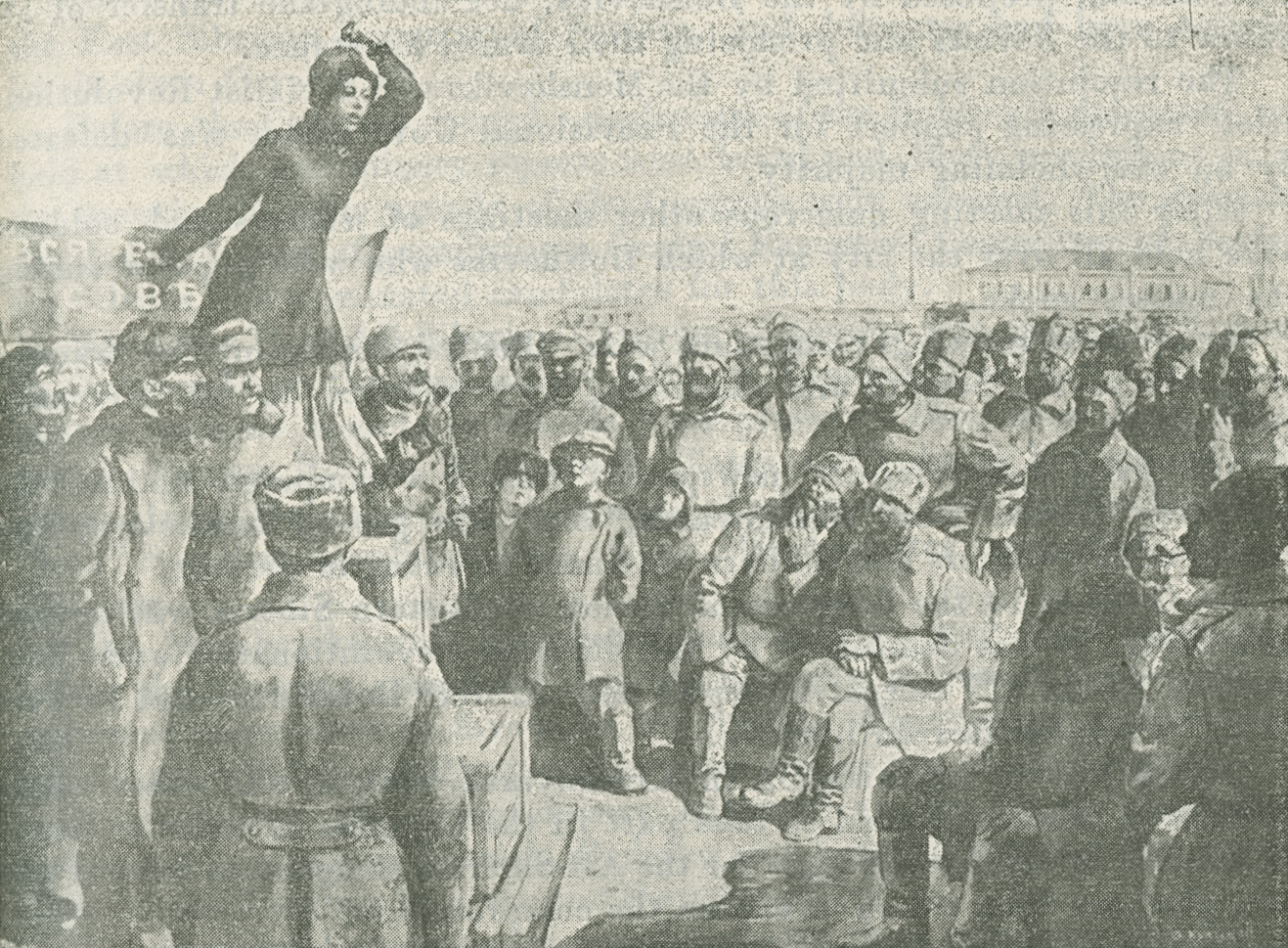

During these days a general meeting of the Bolsheviks in the city was held in the premises of the Railway School at which about 1,000 workers and soldiers were present.

The hall was filled to overflowing. Members of the Irkutsk Committee of the Party and delegates to the Congress of Soviets spoke on the current situation, after which the meeting adopted a resolution defining the Bolsheviks’ aims and tasks in the struggle to win over the masses of Irkutsk and the adjacent districts.

On October 15 over 3,000 soldiers gathered in the Tikhvin Square at a mass meeting called by the Irkutsk Bolsheviks.

The meeting was addressed by the Bolshevik delegates to the All-Siberian Congress. They were supported by the Maximalist Ada Lebedeva. It was strange to hear this little woman with a perky face and boyish way of speaking, delivering vigorous and passionate speeches explaining in plain terms the slogans issued by Lenin.

Born in Irkutsk, the daughter of a Polish exile and a native Siberian woman, she imbibed a hatred for tsarism in her childhood. She joined the Socialist-Revolutionary Party, but in May 1917 broke away from the main body and formed an independent “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary group in Krasnoyarsk. With her at the head of this group were N. Mazurin and Sergei Lazo, who shortly after joined the Bolsheviks.

Lebedeva attended the Congress of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party in Petrograd where she astonished the aged Narodnik, Breshko-Breshkovskaya, by her bold attacks on the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries. Subsequently, she, together with Sergei Lazo, joined the Bolsheviks.

In 1918 she was captured by Whiteguard Cossacks near Krasnoyarsk and hacked to death.

The soldiers’ meeting in Tikhvin Square was also addressed by representatives of the Irkutsk Bolshevik military organisation.

Amidst loud applause the soldiers of the Irkutsk garrison adopted a resolution, proposed by the Bolsheviks, demanding the transfer of all power to the Soviets and promising their armed assistance.

The resolution submitted by the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries expressing support for the Provisional Government was defeated by an overwhelming majority.

After this meeting numerous other meetings of workers and soldiers were held all over the city at which Bolsheviks who were popular among the masses spoke.

At all these meetings resolutions were adopted demanding the transfer of power to the Soviets and expressing no confidence in the Kerensky government.

The local compromisers’ newspapers started a campaign against the “strolling players from Krasnoyarsk,” but this proved ineffective; the masses of the workers and soldiers continued to swing to the left.

On October 10 the Congress of Soviets of Eastern Siberia was opened in Irkutsk. It was dominated by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. Of the 115 delegates present only 32 were Bolsheviks and 15 were “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries.

The Bolshevik organisation in Krasnoyarsk, Kansk, and other towns in Eastern Siberia decided to take part in the Congress in order to use it as a centre in which to prepare for the All-Siberian Congress of Soviets and as a platform from which to expose the compromisers.

Extreme tension prevailed from the moment the Congress opened. A clash was inevitable. It came during the debate on the work of the Area Bureau of Soviets.

The Bolsheviks who declared that the Bureau had not served as an organ of revolutionary power but had followed in the wake of the Provisional Government moved a resolution demanding stern condemnation of the Bureau’s harmful political line. The compromising majority at the Congress, however, passed a resolution expressing confidence in the Bureau.

The debate on the current situation was even more heated. Valentine Yakovlev, the delegate of the Krasnoyarsk Soviet, spoke on behalf of the Bolshevik group, and in a magnificent speech shattered the arguments advanced by the Right Socialist-Revolutionary Timofeyev that the Soviets could not take over power as they lacked the educated people necessary to run the administration.

Yakovlev charged the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries with being in alliance with the bourgeoisie and showed what this alliance was leading to. “Behind Kornilov stands Savinkov,” he declared, and concluded his speech by hurling the accusation at the Socialist-Revolutionaries: “You are betraying the revolution!”

The resolution on the current situation was adopted in the absence of the Bolsheviks and “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries who had withdrawn from the Congress as a protest against the insulting behaviour of the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries.

The First Congress of Soviets of Siberia was to open a few days after the East Siberian Congress of Soviets, and delegates had been arriving for it since October 12.

Before the Congress opened a conference of the Bolshevik delegates was held at which preliminary reports were heard and draft resolutions on all the questions on the agenda of the Congress were adopted. The delegates decided in favour of organising a Central Executive Committee of Soviets for Siberia and nominated candidates for this body.

When the First All-Siberian Congress of Soviets was opened at 7 p.m. on October 16 in the Hall of the Military Topographical Corps, representatives from 69 Soviets in Siberia were present. They came from Vladivostok, Tumen, Harbin, Khabarovsk, Taiga, the Yakutsk Region and other places. In all there were 184 delegates, of whom 65 were Bolsheviks and 35 “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries. Thus, 100 delegates supported a Soviet platform.

The Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries had been aware long before the Congress assembled that the majority of Soviets in Siberia had expressed themselves in favour of the Soviets taking power and anticipated that the Bolshevik Party would come out on top at the Congress.

Consequently, the compromisers hastened to muster reinforcements and sent telegrams to Kirensk, Bodaibo and Yakutsk begging that credentials for the Congress be given to “their men.”

The Socialist-Revolutionaries had made up their minds to obstruct the Congress proceedings and jumped at the first opportunity that offered to do so when a Bolshevik was nominated as chairman of the Congress.

An acrimonious debate ensued. At last the question was put to the vote and by 86 votes against 32, with nine abstaining, a Bolshevik was elected chairman of the First Congress of Soviets in Siberia.

Then commenced the debate on the first item of the agenda, viz., the current situation, the tactics of the Soviets, and the defence of the revolution and the country.

The Right Socialist-Revolutionaries declared that they wanted to postpone the settlement of all questions until the meeting of the Constituent Assembly. The Mensheviks, as usual, wriggled and pleaded for unity among all the forces of revolutionary democracy. The Bolsheviks and “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries insisted on the transfer of all power to the Soviets.

An eloquent speech was delivered by Sergei Lazo, one of the heroes of the struggle for the dictatorship of the proletariat in the Far East. During the Civil War Lazo headed the guerrilla fighters in the Taiga and displayed wonderful courage, resourcefulness and devotion to the revolution. He met with a horrible death, however. In April 1920 he was captured by the Japanese who burned him alive in the furnace of a railway engine.

The speech delivered by Lazo at the Congress was remarkable for its ardour and conviction. “Only when power is transferred to the Soviets,” he said, “shall we be able to direct the unorganised masses into a single channel. We do not oppose the Soviet power to the Constituent Assembly, but we cannot be certain of having a Constituent Assembly unless power is transferred to the Soviets.”[5]

After debating this question for two days the Congress proceeded to take a vote on the resolution that was to determine the political and tactical line of the Soviets in Siberia. The Bolsheviks, supported by the “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries, submitted a resolution which contained the following passage:

“All compromise with the bourgeoisie must be emphatically rejected and the All-Russian Congress of Soviets must take power into its own hands. In the struggle to take over power, the All-Russian Congress can rely on the effective support of the Soviets in Siberia.”[6]

By 93 votes against 68 this resolution was adopted as a basis, subject to amendment.

The Right Socialist-Revolutionaries made another attempt to obstruct the proceedings. They protested against the wording of one part of the resolution which referred to the forthcoming All-Russian Congress as a Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies. The word “Peasants’” they said, should be deleted as the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies, led by Avksentyev, had decided not to take part in the proceedings of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets.

Their motion to this effect was defeated, however, and the resolution was adopted without amendment. When the result of the voting was announced commotion arose in the hall. The so-called “peasant representatives,” most of whom could easily be recognised as local inhabitants, rose from their seats.

“We are leaving the hall,” declared one of these “peasants,” “because we do not wish to violate the decision of the Central Executive Committee of the Soviet of Peasants’ Deputies.”

Thereupon, the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries raised the question as to whether, under these circumstances, the Congress could claim to represent the peasants as well as the workers and soldiers. This question was answered in the affirmative by the Credentials Committee which stated that the Congress was fully justified in calling itself a Congress of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, as representatives were present from Soviets of Peasants’ Deputies as well as from united Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies.

The Socialist-Revolutionaries persisted in their obstruction, however. They made the demagogic statement that the representation at the Congress had been manipulated, that the industrial workers were over-represented, and that most of the peasant deputies at the Congress were soldiers of the local garrison. The Congress rejected this objection. Thereupon the Socialist-Revolutionaries noisily got up from their seats, threw their delegate cards on the presidium table and left the hall. The Congress continued without them.

A number of delegates urged that the proceedings be accelerated so as to enable the delegates to return to their districts as speedily as possible in order to continue the struggle to transfer power to the Soviets.

On October 23 the Congress elected the First Central Executive Committee of Soviets in Siberia known as the Centrosibir.

The Congress elected 14 delegates to the All-Russian Congress of Soviets of whom six were Bolsheviks, one “Left” Socialist-Revolutionary and one Internationalist Social-Democrat.

The representatives of six out of the seven larger towns of Siberia voted in favour of transferring power to the Soviets. Only the seventh, the Omsk Soviet, stood for “transferring power to the democracy.”

In Siberia the period of organising the assault was more protracted than in the other regions of the country owing to the strong influence of the compromisers and the failure of the Bolsheviks immediately to break away from the Unionists.

But even here the Bolsheviks, directed by the Central Committee of the Party, rectified their mistakes, defeated the compromisers and by the eve of the October insurrection had organised a mighty column of reserves for the Great Proletarian Revolution.

[1] “Life in the Province,” (Tomsk), Rabochy Put, No. 16, September 21, 1917.

[2] “The Tomsk Gubernia Conference of Representatives of R.S.D.L.P. Organisations,” Znamya Revolutsii (The Banner of the Revolution), Tomsk, No. 87, September 16, 1917.

[3] “The Meeting of the Joint Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies of September 20, 1917,” Znamya Revolutsii, Tomsk, No. 92, September 22, 1917.

[4] Comrade Lobkov. Published by the History of the Party Board of the Omsk Gubernia Committee of the R.C.P.(B.), 1925, p. 20.

[5] The Congresses. The All-Siberian Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies, Sibir (Siberia), Irkutsk, No. 231, October 22, 1917.

[6] A. Abov, “On the Eve of Red October,” Izvestia of the Eniseisk Gubernia Committee of the R.C.P.(B.), Krasnoyarsk, No. 8, 1922, p. 46.

Previous: In the Urals

Next: The Difficulties of the Struggle to Transfer Power to the Soviets in the National and Border Regions