The Socialist-Revolutionaries always regarded the Volga Region—particularly the middle and lower Volga—as their own special “domain.” It was to this region, that, as far back as the ‘seventies of the last century, the rebels went “among the people,” attracted by the historical traditions of the great peasant revolts led by Stepan Razin and Emelyan Pugachev. The Socialist-Revolutionaries tried to bask in the halo of these great rebels.

During the 1905 Revolution the peasant movement raged more fiercely in the Volga Region than in any other part of the country. It was here, amidst the glare of the burning estates of the nobility and the ominous sound of the tocsin, that Stolypin, then Governor of Saratov, introduced his system of combating the peasant revolt. Promoted by Nicholas II from Provincial Governor to Cabinet Minister, Stolypin tried to save the tottering empire by his agrarian policy.

Historical traditions were not the main factor, of course. Traditions grow out of and are fostered by a definite economic soil. In 1861, during the emancipation of the serfs, the landlords robbed the Volga peasants of 25 per cent of their land, and in the Saratov and Samara Gubernias of as much as 40 per cent. The peasants were driven “into the sands,” or were obliged to settle on wretchedly small plots. In the Saratov Gubernia one-third of the peasants, nearly 35 per cent, were known as darstvenniki(*), as at the time of the emancipation they were freed gratis, i.e., without having to pay compensation, but they received only one-quarter of an allotment. This explains the turbulent character of the agrarian movement in the Volga Region.

During the war the Volga Region was converted into a huge army base. Big garrisons were quartered in the towns—60,000 troops in Samara, 30,000 in Saratov, while Kazan was the centre of one of the largest military areas, which included all the garrisons in the region. On January 1, 1917, the total number of troops concentrated in the Kazan Military Area reached 800,000, of whom officers alone numbered 20,000. On the eve of the October Revolution the garrison of the city of Kazan numbered nearly 60,000 men.

Hypocritically flaunting the slogan “Land for the Peasants!” but actually defending the landlords, the Socialist-Revolutionaries made capital out of the yearning of the soldiers and backward workers for land. This enabled them in the early days of the February Revolution to entrench themselves in the rural districts, in the garrisons, and even in certain large factories. Whole regiments expressed their support for the Socialist-Revolutionaries who in the Volga Region during the election of the Constituent Assembly in November 1917, succeeded in polling 70 per cent of the vote. The task that confronted the Volga Bolsheviks was to win the region away from the Socialist-Revolutionaries.

The speedy realisation of this aim was facilitated by the fact that in 1917 there were considerable numbers of industrial workers in the large towns of the Volga Region, such as Samara, Nizhni-Novgorod, Tsaritsyn and Saratov, with whose aid the Bolsheviks succeeded in destroying the influence of the Socialist Revolutionaries in the rural districts and among the soldiers in the army barracks.

In 1917, the Samara Pipe Works employed 23,000 workers, and the Sormovo Works, in Nizhni-Novgorod, 25,000. A similar number was employed in the factories in the Kanavino District of Nizhni-Novgorod. Of the 200,000 population of Tsaritsyn, 35,000 were industrial workers, of whom some 7,000 were metalworkers employed mainly in the two largest enterprises in the town—the French Works and the Ordnance Works. Kazan was a large industrial centre for those times, with 20,000 workers, half of whom were metalworkers. Even in Saratov, then a typical Volga trading town, there were from 12,000 to 15,000 workers out of a total population of 250,000.

During the war the munitions industry developed very rapidly in the cities along the Volga, and large numbers of workers came to the factories from the rural districts, bringing with them their hatred of landlordism, but also their rural backwardness and prejudices. Large numbers of the petty bourgeoisie in the towns flocked to the factories in order to evade military service.

All this created favourable soil for the activities of the Socialist-Revolutionaries. At the Pipe Works, in Samara, for example, where the Bolsheviks had their strongest organisation, numbering over 2,000 members, the Mensheviks had only 300 members, but the Socialist-Revolutionaries had about 12,000. At the Sormovo Works, in Nizhni-Novgorod, out of a total of 25,000 workers, the Socialist-Revolutionaries had a membership of 10,000. The influence of the Socialist-Revolutionaries was least marked in Tsaritsyn.

As the days and months of the revolution passed by, however, the Bolshevik organisations in the Volga Region grew and became more strongly entrenched.

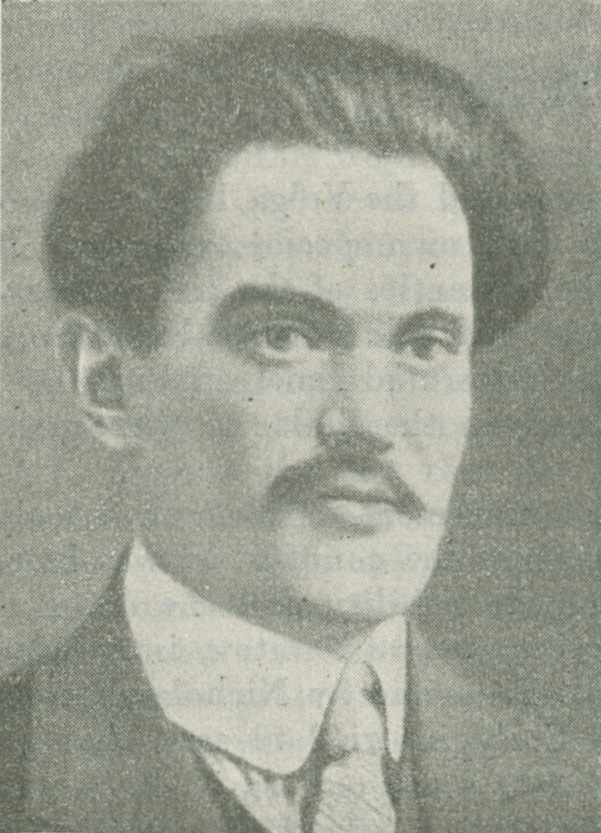

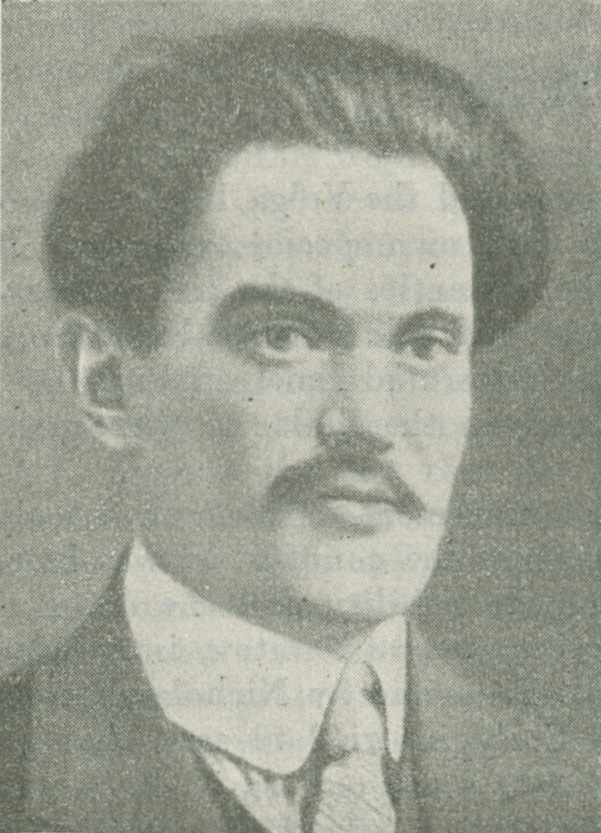

The Bolsheviks had their largest organisation in Samara. At the time of the Sixth Party Congress they already had 4,000 members in that city. The growth of the Samara Bolshevik organisation was due largely to the work of Valeryan Vladimirovich Kuibyshev, who came here in 1916, after his escape from exile. Under the name of Adamchik he obtained a job as a lathe hand at the Pipe Works where he operated a machine next to that of N. M. Shvernik.

In September 1916, Kuibyshev was arrested and exiled to Siberia for five years. While on the way to his place of exile news came through of the outbreak of the February Revolution, and Kuibyshev hastened back to Samara, which he reached on March 17, 1917. He was given an official welcome by the working people of the city, the workers from all the factories coming out with banners to meet him. On March 21, only a few days after his arrival, Kuibyshev was elected Chairman of the Workers’ Section of the Samara Soviet, in spite of the fact that at that time the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks predominated in the Soviet.

Kuibyshev set to work to strengthen the local Bolshevik organisation. He organised a big meeting at the Triumph Cinema at which he strongly denounced those who tried to obliterate the distinction between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. A City Committee and District Committees of the Party were set up which firmly pursued the line of no amalgamation with the Mensheviks. It was on this principle that the Bolshevik organisations in the city of Samara and the Samara Region were built up.

The Samara Bolsheviks started their campaign to win over the masses in the factory committees and trade unions. Here they concentrated their best forces. In May, Shvernik became Chairman of the Metal Workers’ Union, the Bolshevik Galaktionov became Vice-Chairman, and Kuibyshev a member of the Executive. On August 29, the workers at the Pipe Works elected a new factory committee consisting almost entirely of Bolsheviks. The Executive Board of the factory committee consisted of 18 Bolsheviks and two Socialist-Revolutionaries. Unit after unit—metal-workers, builders, food-workers and railwaymen—unanimously cast its vote for the Bolshevik Party.

The same process, although somewhat slower, went on in the army barracks where the 102nd, 133rd and 143rd Infantry Regiments, a Reserve Regiment of the Sappers, the 4th and 5th Batteries of the Reserve Artillery Brigade and other units were stationed. A Bolshevik military organisation was set up in Samara and a Bolshevik newspaper, Soldatskaya Pravda was published for the benefit of the soldiers. The influence of the Socialist-Revolutionaries was overcome fairly quickly.

In the course of August and September the Bolsheviks gained complete control of the Soviet. On August 21 the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies adopted by 97 votes against 72 a Bolshevik resolution urging the necessity of combating the counter-revolution. In this way the Bolsheviks, step by step, gained the majority in the Soviet.

In Saratov a strong Bolshevik group was formed during the period of the imperialist war. The group consisted of Olminsky—who, jointly with Lenin, had edited the Bolshevik central organ in the period of the first revolution—Mitskevich, and others. They published a legal Bolshevik organ called Nasha Gazeta.

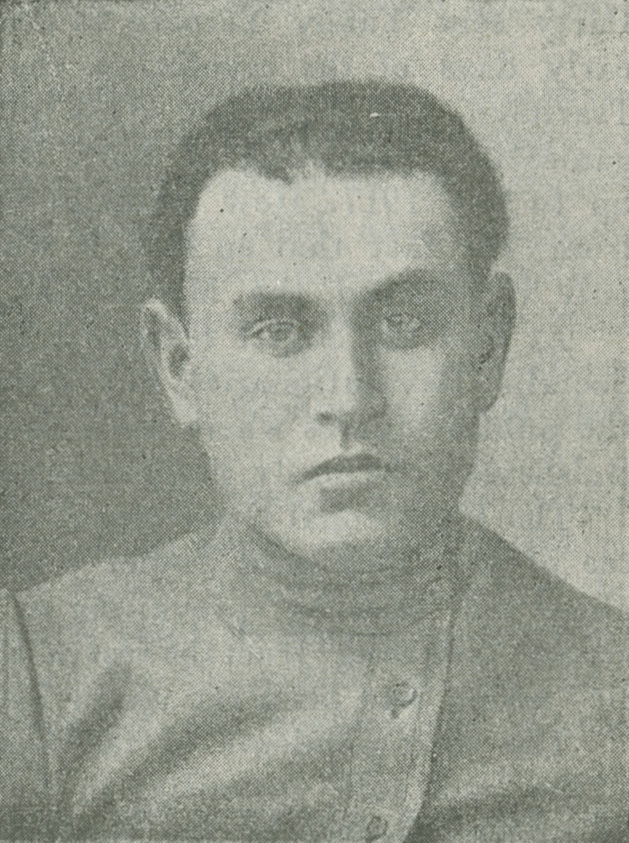

As soon as the Bolshevik Party became legalised in March 1917, the Saratov Bolsheviks formed their own independent organisation, and on the 23rd of that month they issued the first number of the Bolshevik newspaper Sotsial-Demokrat. Among those participating in the work of the Saratov Party organisation was Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich. A representative of the Pravda generation of Bolsheviks and in 1917 having already had seven years’ experience of active Party work, arrests and exile, he came to Saratov in May 1917 as a private in the 7th Company of the 42nd Infantry Regiment. A brilliant orator, he had the gift of speaking to the people in a language they could understand. Vital and energetic, Kaganovich appeared at meetings at the crucial moment when it seemed that some Socialist-Revolutionary or Menshevik “spellbinder” had succeeded in swaying the audience. Crushing the compromisers with his biting sarcasm and silencing interrupters with his witty repartee, Kaganovich succeeded with his ardour and eloquence in winning the audience to his side. The soldiers and workers listened to him with rapt attention.

The effects of the Bolsheviks’ activities were seen first of all in the rapid Bolshevisation of the Saratov Soviet. Thus, the second Soviet (June-August) consisted of 90 Bolsheviks, 210 Mensheviks and 310 Socialist-Revolutionaries. After the election of the third Soviet at the end of August the situation underwent a radical change; the relative strength of the parties was as follows: Bolsheviks 320, Mensheviks 76, Socialist-Revolutionaries 103. The Bolsheviks thus had an absolute majority.

In Tsaritsyn there was no definite Bolshevik organisation before the war, although a few individual Bolsheviks worked secretly in different factories. In 1914 Klement Efremovich Voroshilov was employed at the Ordnance Works. A veteran Bolshevik, who had gone through the stern school of revolution, he succeeded in evading the vigilance of the secret police. In Tsaritsyn he formed a workers’ co-operative society and a workers’ choir, and under cover of these “innocuous” bodies he conducted Bolshevik agitation and propaganda. The Bolsheviks whom Voroshilov trained took an active part in the revolutionary struggle.

The bourgeois-democratic revolution of February 1917 opened the sluice gates which had held back the revolutionary energy of the Tsaritsyn proletariat, and the revolutionary activities of the workers of Tsaritsyn burst forth like a spring flood. Mass meetings were held in the Skorbyashchenskaya Square where the workers listened to the Bolsheviks for hours, the meetings often lasting far into the night. Here, in this tense atmosphere, the minds of the workers matured with exceptional rapidity. To the square came the soldiers from the garrison, and in this close communion the influence of the proletariat spread over these peasants in soldiers’ uniform.

It seemed for all the world as if the meetings on the Volga called to the meetings held in the Baltic. In Kronstadt, thousands of sailors gathered in the open air in Yakornaya Square. The bourgeoisie soon perceived this close connection, and in their newspapers references to Red Kronstadt were more and more often coupled with references to Red Tsaritsyn.

In the beginning of April 1917, the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party sent Yakov Yerman to conduct Party work in Tsaritsyn. In the early days of the revolution, the Trotskyite S. Minin also appeared in Tsaritsyn, and as a result of his influence the united Social-Democratic organisation, consisting of both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, existed right up to May 1917. How artificial this temporary unity was may be judged from the fact that on May 9, when the split took place, of 380 members only 30 followed the Mensheviks.

At first the Soviet remained under the control of the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, but in the factories, in the army barracks and in the public squares where mass meetings were continually in progress, the Bolsheviks obviously predominated.

The Provisional Government in Petrograd and the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet continued to receive alarming information about the “anarchy” prevailing in Tsaritsyn, about the imminence of Tsaritsyn “seceding” from the rest of Russia, and about the “Bolshevik republic” which had been set up in Tsaritsyn.

The correspondents of the bourgeois newspapers sent lurid accounts of the “mob rule” prevailing in the town. “The city is in the hands of mobs of soldiers incited by the Bolsheviks,” reported one of them.[1]

The enemies of the revolution wrote about Tsaritsyn with venom and hatred, but the workers all over the country spoke about it with pride.

Becoming bolder after the July days, the counter-revolution began to tackle Red Tsaritsyn. On July 26, by order of the Provisional Government and with the complicity of the Saratov and Tsaritsyn Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries, a punitive expedition arrived from Saratov under the command of Colonel Korvin-Krukovsky. The unit consisted of 500 cadets and 500 Orenburg Cossacks equipped with fourteen machine guns and two three-inch field guns. Martial law was proclaimed and all meetings were prohibited. The Bolshevik newspaper Borba was suppressed. The 141st and 155th Regiments, the most revolutionary units of the Tsaritsyn garrison, were hastily sent out of the city, one to Saratov and the other to the front. The elections to the City Duma, in which the Bolsheviks had won 39 of 102 of the seats, were annulled and new elections were appointed for the end of August.

The new elections were held on August 27, while Korvin-Krukovsky’s punitive unit was still in the city. The elections proved that its presence had not intimidated the workers. The Bolsheviks secured 45 of the 102 seats, the Mensheviks 11 and the Socialist-Revolutionaries 15. The Bolshevik Yerman was elected Chairman of the City Duma.

In the speed with which it mobilised the masses Tsaritsyn outpaced not only the capital of the gubernia, Saratov, but also the other important centres of the Volga Region, such as Samara and Nizhni-Novgorod. This was due primarily to the fact that in Tsaritsyn the enemy who had to be isolated—the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks—was much weaker than in the other Volga cities.

In Nizhni-Novgorod the struggle for power was more difficult and fierce than in any other Volga city.

In Sormovo and in Nizhni-Novgorod united Bolshevik and Menshevik organisations existed right up to the end of May. The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party had to send a special instruction to the Sormovo and Nizhni-Novgorod Bolsheviks ordering them to break away completely from the Mensheviks and to form their own independent organisation. This opportunist dread of breaking with the compromisers was the main reason why the process of winning the masses from the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks was much slower in Nizhni-Novgorod than in the other Volga centres.

An important factor in bringing about this change was the strike at the Sormovo Works, which broke out on June 20 and ended in victory on July 8. In the course of this strike the workers, under the leadership of the Bolsheviks, took the first steps in organising workers’ control of industry. On June 27 the Sormovo Committee of the Bolshevik Party adopted a resolution calling for the confiscation of the works.

The Sormovo Works was engaged on war contracts, and the fact that it had been brought to a standstill alarmed the capitalists. The government sent a commission of enquiry to the plant, but the workers displayed such firmness that at a general meeting of the Sormovo organisations the commission was obliged to promise that all the workers’ demands would be conceded. Only after this was the strike called off.

The workers learned a great deal from this strike, and it helped them shed the illusions about the possibility of compromise under which many of them had laboured.

In the middle of August the workers, at mass meetings held at nearly all the factories in Nizhni-Novgorod, passed resolutions against the Moscow Conference. The columns of the Bolshevik newspaper International were filled with these resolutions.

The Nizhni-Novgorod Soviet was controlled by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks, but even in this stronghold of the compromisers the Bolshevik vote steadily increased. At a meeting of the Soviet held on September 10, at which the functions of the Democratic Conference were discussed, 62 votes were cast for the Bolshevik resolution and 69 against.

At this time the peasant movement in the Nizhni-Novgorod Gubernia assumed enormous dimensions.

Cases of the seizure of landlords’ estates and the division of their land became more frequent. Throughout 1917 there were no less than 384 cases of peasant agrarian disturbances in the Nizhni-Novgorod Gubernia.

On the eve of the October Revolution there was a strong mass peasant movement also in the Kazan Gubernia. In a report of the Chief Administration of the Militia on the Kazan Gubernia dated October 18 we read the following:

“In nearly all the uyezds in the gubernia there are numerous cases of wholesale felling of private woods . . . the forcible sale of livestock and farm implements, the confiscation of grain, hay and fodder and the expulsion of the administration.”[2]

The Tatar workers and peasants and the other Volga nationalities in the Kazan Gubernia, such as the Chuvash and Mari, rose up to fight for their national liberation. The intricate interweaving of nationalities, the fierce struggle against the nationalist counter-revolution, and the presence of considerable Whiteguard forces, all served to intensify the struggle in Kazan.

Nevertheless, the Bolshevik organisation in the city steadily extended its influence over the masses. On the eve of the October Revolution the Bolsheviks won a majority in the Kazan Soviet.

Thus, the Bolshevik organisation in the Volga Region steadily advanced towards the conquest of power. By September, the Samara, Saratov and Tsaritsyn Soviets were entirely under the control of the Bolsheviks. Only in Nizhni-Novgorod was the Soviet still controlled by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks, but, as these compromisers themselves were forced to admit, the Soviet no longer expressed the sentiments of the masses.

The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party devoted considerable attention to the Volga Region in drawing up its plans for the insurrection. It sent to Saratov one of its representatives who, on October 8, at a general meeting of the Party members in the city, reported on the course the Central Committee had taken towards an insurrection. On October 11, the Saratov Committee of the Party held a joint meeting with representatives of the uyezd towns, such as Tsaritsyn, Volsk, Petrovsk and Rtishchevo, at which it was decided to mobilise all forces for the purpose of touring the whole gubernia. On October 15, a Regional Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies was opened in Saratov at which the Bolsheviks predominated. The report on the political situation was made by Comrade Yerman, who was in Saratov at that time. In the course of his report he clearly and concisely conveyed to the Congress the political line of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party.

By a majority of 128 votes against 12 the Congress adopted the Bolshevik resolution, whereupon the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries demonstratively withdrew from the Congress.

The “chief reason for our withdrawal,” they stated, “is the rejection by the majority at this Congress of the resolution which called for abstention from street demonstrations.”[3]

Thus, from the Central Committee to Saratov, from Saratov to the various uyezd towns throughout the region, right up to Tsaritsyn, came the clear and definite instruction to prepare for the armed struggle for power.

On October 6, a Gubernia Congress of the Bolshevik Party was opened in Samara. This Congress elected a Gubernia Committee with Kuibyshev as Chairman.

On October 22, a few days before the October insurrection, a joint meeting was held of the Bureau of the Gubernia and City Committees of the Party with representatives from the districts. At this meeting the question of making practical preparations for the insurrection came sharply to the front.

Kuibyshev demanded that “actual operations be started.”

The meeting adopted the following resolution:

“That resolute measures be undertaken, such as suppressing the newspaper Volzhsky Dyen, arresting provocateurs, floating a compulsory loan, abolishing queues, etc., etc. The resistance of the bourgeoisie to these measures will stimulate the energy of the masses and then, having the majority behind us, and with the launching of similar operations in the majority of other cities throughout Russia, to proclaim the dictatorship of the Soviets.”[4]

Intense preparations for the insurrection were also made in Nizhni-Novgorod.

Soon after the Central Committee had made its historic decision on armed insurrection a meeting of the Nizhni-Novgorod Gubernia Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.) was held at which the following decision was adopted:

“Be ready to do everything at the proper moment to ensure a successful insurrection.”[5]

In September, and particularly in October, the Bolshevik organisations in the Volga Region energetically armed the workers.

The first to start was Samara. Already at the beginning of May, a Workers’ Militia was formed to cope with “drunken riots,” i.e., the raiding of wine shops, and so forth.

On September 29, the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, after hearing a report by Kuibyshev, endorsed the main points of the Workers’ Red Guard Regulations.

In September, the formation of Red Guard units began in Saratov. On September 2, the Executive Committee of the Saratov Soviet decided to form combat groups, and in October, the Soviet appealed to the Moscow Soviet for assistance in the way of arms for the Red Guard. In October, the Railwaymen’s Red Guard alone numbered 700 men. On October 22, a City Conference of the Red Guard was held at which the Regulations were adopted.

On October 15, a joint meeting of representatives of the Red Guard of Kanavino, Sormovo and Myza was held at which the question of procuring arms for the Red Guard was discussed. Sormovo needed 285 rifles and Kanavino and Myza 200 each. A week later, the Gubernia Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.) set up a Gubernia Headquarters Staff for the Red Guard.

In Tsaritsyn, the arming of the workers began long before the October Revolution, and in the period of the Kornilov mutiny it was conducted on a mass scale. The pioneers in this matter were the workers employed in the two leading plants—the Ordnance Works and the French Works. The Volgo-Donskoi Krai, a bourgeois newspaper published in Tsaritsyn, reported the following:

“On the night of August 30, a group of members of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.) took several waggon loads of rifles and cartridges from the stores of one of the companies of the 93rd Regiment for the purpose of arming the workers. That same night the rifles were served out to the workers in the French Works and at the saw mills.”[6]

This incident raised quite a furore.

On August 30 the punitive detachment commanded by Korvin-Krukovsky was recalled from Tsaritsyn, but before leaving the city the Colonel issued his last “threatening” order demanding the immediate surrender of the arms captured by the workers. Nobody, of course, paid any attention to this order. Very soon the workers needed these weapons to fight the Kornilovites.

The arming of the Tsaritsyn workers proceeded at a rapid pace throughout September and October. At that time the Tsaritsyn Red Guard numbered about 750 men.

The Central Committee’s directions to prepare for an insurrection were effectively carried out by the Bolshevik organisations in the Volga Region.

To the Second Congress of Soviets Samara sent three Bolshevik delegates, Tsaritsyn two Bolshevik delegates, Saratov two Bolsheviks and one Menshevik, and Nizhni-Novgorod five Bolsheviks and several Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. The overwhelming majority of the delegates from the Volga Region carried to the Second Congress of Soviets the instruction: “All power to the Soviets!”

[*] From the Russian word “darom,” i.e. “gratis”—Trans.

[1] “Anarchy and Counter-Revolution in Tsaritsyn,” Rech, No. 128, June 3, 1917.

[2] Central Archives of the October Revolution, Fund 406, Catalogue No. 69, File No. 306, folios 42-44.

[3] “The Regional Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies,” Proletary Povolzhya (The Volga Proletarian), No. 116, October 18, 1917.

[4] “The Joint Meeting of the Bureau of the Gubernia Committee and the City Committee of the Bolshevik Social-Democrats with Representatives in the District,” Privolzhskaya Pravda (Volga Truth), Samara, No. 145, October 22, 1917.

[5] Ibid.

[6] 1917 in the Stalingrad Gubernia (Chronicle of Events). Compiled by G. G. Gavrilov, Stalingrad, 1927, p. 90.

Previous: The Moscow Bolsheviks Prepare for Insurrection

Next: In the Don Region