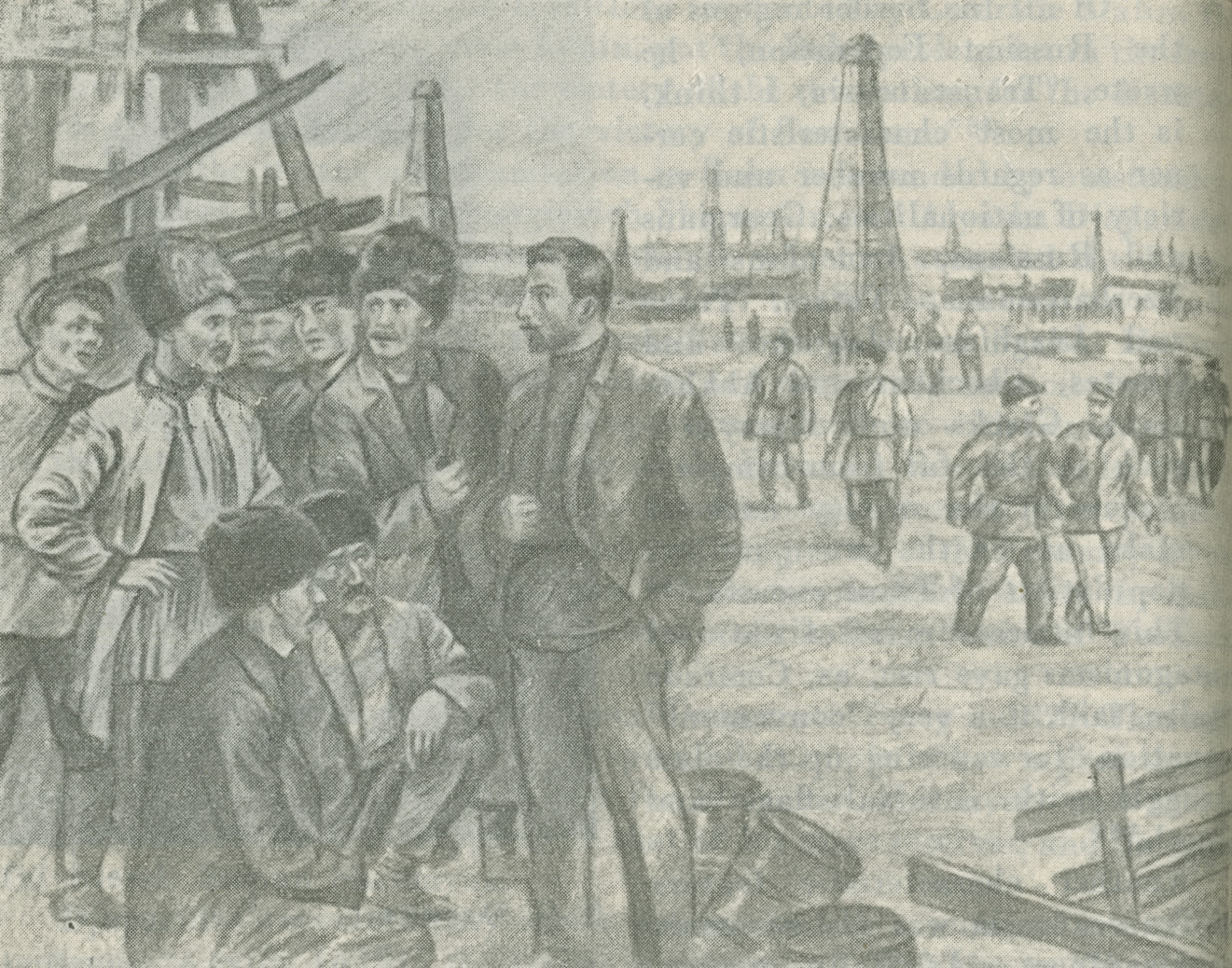

The pioneers in the struggle for the victory of the proletarian revolution in Transcaucasia were the proletariat of Baku. Baku was, as Stalin said, the industrial oasis of the region. Here were concentrated the largest oilfields and refineries, and the decisive forces of the proletariat who had a splendid militant revolutionary past.

Before the revolution the total number of industrial workers in Transcaucasia was about 100,000, of whom over 36,000, 38 per cent, were employed in the Baku oilfields. In Tiflis, which was the commercial and administrative centre of the Caucasian Dominion, there were hardly any large industrial enterprises except for the main railway workshops. In Erivan, which before the revolution had a population of barely 30,000, there was no industrial proletariat at all. In Kutais there were only several hundred industrial workers in all. All this served to make Baku the centre of the revolutionary movement in Transcaucasia.

The Bolshevik organisation in Baku was formed, grew and matured under the direct leadership of Stalin. As L. P. Beria wrote:

“The glorious Bolshevik traditions implanted by Comrade Stalin, the closest colleague of our great Lenin, put the Baku proletariat in the front ranks of those fighting for the victory of the revolution, for the dictatorship of the proletariat, for the victory of Socialism.”[1]

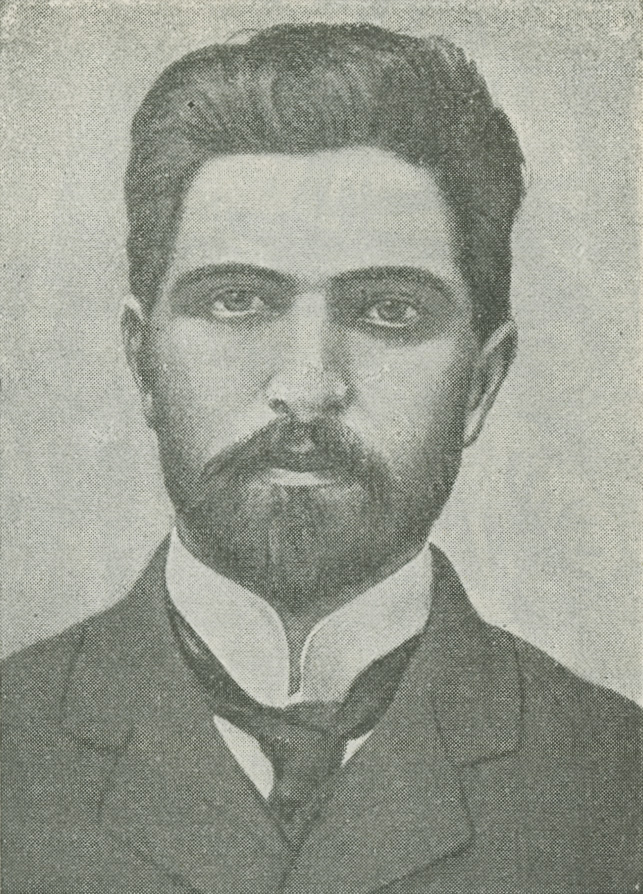

In 1917 the Bolshevik organisation in Baku was headed by outstanding Party leaders like Stepan Georgievich Shaumyan and Alyosha Djaparidze. Stepan Shaumyan was a veteran Bolshevik who had attended the Fourth and Fifth Congresses of the Party. From 1907 to 1911 he carried on revolutionary work in Baku under the immediate guidance of Stalin. He was extremely popular with the Baku workers and exercised enormous influence among them. For many years he kept up a correspondence with Lenin, mainly on the national question. At the time of the February Revolution he was in Saratov, where he had been exiled by the tsarist government after spending ten months in prison. Immediately on receiving news of the February Revolution he left for his native city, Baku. On the way he learned that the Baku workers had elected him the first Chairman of the Baku Soviet of Workers’ Deputies.

Alyosha Djaparidze joined the Social-Democratic Party in 1898. Throughout his life he, like Shaumyan, set a splendid example of how a professional revolutionary should live and fight for his cause. His lively and ardent temperament seemed to supplement that of his more reserved and thoughtful friend, Stepan Shaumyan.

Djaparidze’s revolutionary career was marked by a series of arrests and sentences to exile. In 1915 the tsarist government exiled him to Siberia but soon he escaped and, on the instructions of the Party, conducted revolutionary activities among the soldiers in the Caucasian Army.

After the February Revolution he was recalled to Baku from Trapezund, where he had been engaged in revolutionary activities.

After the All-Russian April Conference of the Bolshevik Party the Transcaucasian Bolsheviks, on the direct instructions of Lenin and Stalin, broke with the Menshevik organisation and formed independent Bolshevik organisations in Baku, Tiflis, Batum and other Transcaucasian cities. On March 11, the first issue of the Bolshevik newspaper Kavkazsky Rabochy appeared in Tiflis. On April 22 the Bolsheviks in Baku published the first issue of their newspaper the Bakinsky Rabochy, the same title as that borne by the newspaper which Stalin had edited in the period of 1906-08.

Firm Bolshevik leadership and this newspaper were powerful assets in the struggle the Baku Bolsheviks waged to transform the bourgeois-democratic revolution into a Socialist revolution.

Nevertheless, grave difficulties were encountered in the process of winning the masses for Bolshevism and of capturing power.

Comrade Stalin later pointed to two specific features of the movement in Transcaucasia, which left their impress on the course of the proletarian revolution.

“Of all the border regions of the Russian Federation,” he wrote, “Transcaucasia, I think, is the most characteristic corner as regards number and variety of nationalities. Georgians and Russians, Armenians and Azerbaijanians, Tatars, Turks and Lezghians, Ingushes and Ossetes, Chechens and Abkhasians, Greeks and Kumyks—such is the far from complete picture of the motley national make up of the seven million population of Transcaucasia.”[2]

This intricate maze of national antagonisms gave rise, as, Comrade Stalin said, to a very “convenient” situation “for covering up the class struggle with national flags and tinsel.”[3]

Another characteristic feature of Transcaucasia was its economic backwardness. As Stalin wrote:

“If we leave out Baku, that industrial oasis of the region, which is run mainly by foreign capital, Transcaucasia is an agrarian country with commercial life more or less developed on its borders, on the seacoast, and with still strong survivals of purely feudal society in the interior.”[4]

The Baku proletariat, among whom there were many Russian workers, had but slight contact with the rural districts of Azerbaijan, and this inevitably affected the course of the proletarian revolution in Transcaucasia.

In March 1917, the Provisional Government set up an administrative body known as the Special Transcaucasian Committee to replace the Viceroy of the Caucasus and Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasian Front, N. N. Romanov. This Committee was glaringly counter-revolutionary in character and so, to pacify the masses, the government was obliged to add the Menshevik Chkhenkeli to the Committee. All the regional directing bodies in Transcaucasia, such as the Regional Centre of the Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies and the Soviet of the Caucasian Army, were controlled by the Georgian Mensheviks, who had entered into a bloc with the Socialist-Revolutionaries and the bourgeois-nationalist organisations.

Even the Baku Soviet of Workers’ Deputies, of which the Bolshevik Stepan Shaumyan had been elected the first chairman, was dominated by the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries.

Taking advantage of the merging of the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies with the Soviet of Soldiers’ Deputies, which in Baku took place in May 1917, the compromisers succeeded in electing their nominee, the Socialist-Revolutionary Saakyan, as Chairman of the Joint Soviet, in place of Shaumyan.

The Georgian Mensheviks, in alliance with the bourgeois-nationalist organisations, the Dashnaktsutyun (the Armenian bourgeois-landlord party) and the Mussavat (the Azerbaijan bourgeois-landlord party), did their utmost to divert the attention of the masses from the class struggle by fomenting national antagonisms and national strife.

The Dashnaks and Mussavatists welcomed the Provisional Government and supported it with might and main. These bourgeois-nationalist organisations, particularly during the first few months after the February Revolution, succeeded by means of demagogic slogans in winning over large masses of the working people of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia, mainly in the rural districts.

The Transcaucasian Bolsheviks had to wage a long and persevering struggle to win the masses.

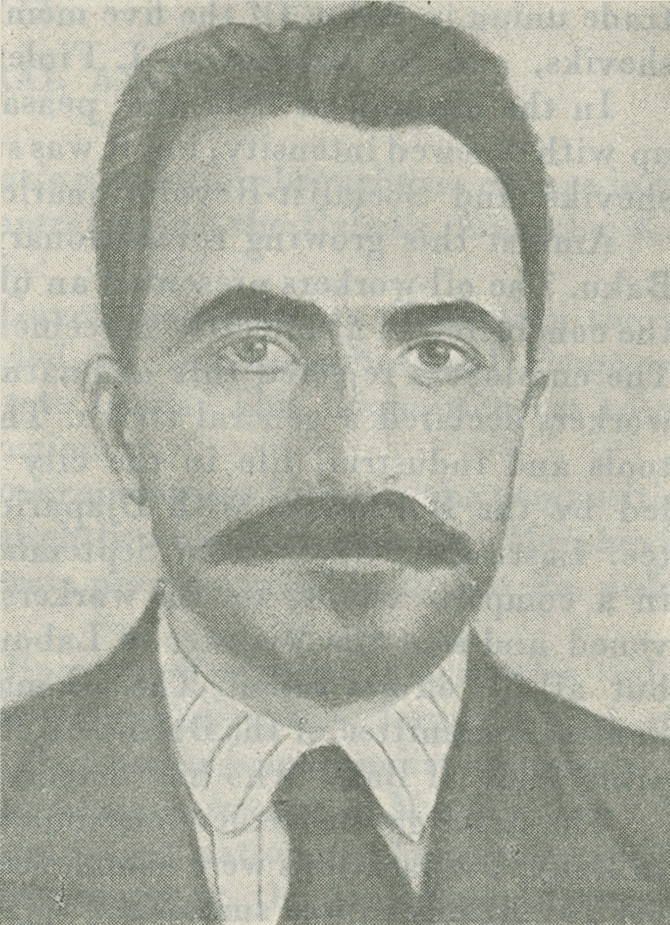

Among the Mohammedan section of the working people an important part was played by the Gummet (Energy) organisation, which was headed by the veteran Bolshevik, Meshadi Azizbekov. The Gummet was affiliated to the Baku Bolshevik organisation and published its own newspaper in the Azerbaijan language. The Sixth Congress of the Bolshevik Party greeted the Gummet as the first Social-Democratic organisation among the Mohammedans. A number of nationalists, masking their true political opinions, managed to worm their way into the organisation, however, and did everything to prevent the masses of the various nationalities from rallying around the Bolshevik Party. Moreover the organisation had only slight influence in the rural districts. Yet, despite these drawbacks, and the mistakes it committed, it succeeded in carrying on extensive Bolshevik activities in 1917, which produced important results.

At the Sixth Congress of the Bolshevik Party the Baku Bolsheviks were represented by Alyosha Djaparidze. In Petrograd he met Stalin and Sergo Orjonikidze, from whom he received the necessary instructions concerning the further objects of Bolshevik work in Transcaucasia. The Sixth Congress elected Stepan Shaumyan a member of the Central Committee and Alyosha Djaparidze an alternate member.

Guided by the decisions of the Sixth Congress, the Bolsheviks in Transcaucasia intensified their efforts with the object of swinging the Soviets to their side and of capturing power.

After the July days, and especially after the Kornilov mutiny, the situation in Transcaucasia, particularly in Baku, underwent a radical change.

On August 30, 1917, the Baku Soviet, at a meeting at which, besides the members of the Soviet, about a thousand representatives of workers and soldiers were present, for the first time adopted a Bolshevik resolution.

A demand, strongly backed by the masses, was made for the election of a new Soviet. The old Soviet was dissolved and the campaign for the election of the new Soviet was started in September. The Bolsheviks gradually gained influence also in the trade unions. In May 1917 they had already gained the leadership in the Oil Workers’ Union, the largest and leading trade union in Baku. Of the five members of the Presidium, three were Bolsheviks, and the Bolshevik, I. Fioletov, was chairman of the Executive.

In the autumn of 1917 the peasant movement in Transcaucasia flared up with renewed intensity, but it was suppressed by armed force by the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries.

Amidst this growing revolutionary crisis a general strike broke out in Baku. The oil-workers presented an ultimatum to the employers demanding the conclusion of a collective agreement on terms which they had drawn up. The employers rejected this ultimatum, whereupon, on September 27, the workers declared a general strike. The entire proletariat of Baku downed tools and industrial life in the city came to a standstill. The strike was led by the Bolsheviks with Djaparidze as chairman of the strike committee. Lasting six days—from September 27 to October 2—the strike ended in a complete victory for the workers. The Provisional Government intervened and sent the Minister of Labour to Baku to arrange a compromise, but all his efforts failed. The oil magnates were compelled to yield. The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party congratulated “the revolutionary proletariat of Baku who has defeated organised capital in open battle.”[5]

The strike gave a tremendous impetus to the growth of Bolshevik influence in Baku. Preparations were commenced for the decisive battles. On September 15 Shaumyan was summoned to Petrograd, where he attended the meeting of the Central Committee of the Party at which Lenin’s letters on armed insurrection were discussed.

On returning to Transcaucasia, Shaumyan directed the proceedings of the First Congress of Bolshevik organisations in the Caucasus, which was held in Tiflis from October 2 to 7. The decisions adopted at this Congress were based on the Central Committee’s directions on armed insurrection. It also passed a resolution on the national and agrarian questions. These decisions were supported by all the Party organisations except the Tiflis group, which held the mistaken opportunist view that it was possible to capture power “peacefully” and reach an agreement with the Mensheviks. The treacherous line pursued by this group, however, had serious consequences and served to protract the struggle for the transfer of power to the Soviets in all the decisive centres of Transcaucasia except Baku.

In the middle of October the Bolsheviks gained control of the Baku Soviet. At the meeting held on October 13 the Menshevik and Socialist-Revolutionary Executive Committee resigned and a Provisional Executive Committee headed by Shaumyan was elected. On October 15 a joint meeting of the Soviet with representatives of the workers and soldiers was held at which delegates to the Second All-Russian Congress were elected and a resolution was passed urging the necessity of depriving the enemy of power and of transferring it to the people represented by the Soviet of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies.

Thus, surmounting all the difficulties in their way, the Bolsheviks of Baku firmly and confidently marched toward the seizure of power.

[1] L. Beria, On the History of the Bolshevik Organisations in Transcaucasia, Eng. ed., p. 164.

[2] J. Stalin, “The Counter-Revolutionaries in Transcaucasia Under the Mask of Socialism,” Pravda (Truth), No. 55, March 26, 1918.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] “Greetings,” Rabochy Put, No. 29, October 6, 1917.

Previous: The Baltic Provinces

Next: Central Asia