In 1917 Byelorussia was in the war zone. The country was intersected from end to end with the trenches and barbed wire entanglements of the three armies of the Western Front. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers garrisoned the cities. Moghilev was the headquarters of the Supreme Command, where the generals were hastily mustering forces to crush the revolution. Through the large railway junctions, such as Minsk, Gomel, Vitebsk and Orsha, troop trains passed from the front, carrying troops to be used against revolutionary Petrograd. All this gave exceptional importance to the struggle for the victory of the revolution in Byelorussia. It was essential to wrest this extremely important place d’armes from the counter-revolution.

The first Bolshevik organisation in the region was formed in Gomel, where a Bolshevik Committee was set up as early as April 1917. This Committee preserved the name of Polessye Committee, by which the local Bolshevik organisation had been known before the revolution.

The activities of the Polessye Committee extended far beyond Gomel to all parts of the Moghilev Gubernia, as well as to Moghilev itself, the gubernia capital. The Committee’s activities were greatly stimulated by the arrival in Gomel, in August 1917, of L. M. Kaganovich, who was elected Chairman of the Polessye Committee.

Kaganovich made contact with the industrial workers, sent instructors, organisers and propagandists to the districts, saw to all details of Party work, visited the study circles, and supervised the activities of the Party workers.

He personally took charge of Party work in the most difficult districts. One of these was Moghilev, the headquarters of the Supreme Command. There was as yet no independent Bolshevik organisation in Moghilev; the Bolsheviks belonged to the united Social-Democratic organisation. The city was inundated with counter-revolutionary officers and this hindered the work of revolutionary propaganda. Kaganovich managed to establish connection even with a battalion of the Chevaliers of St. George who guarded General Staff Headquarters, and formed a Bolshevik organisation among them.

In Minsk the Bolsheviks withdrew from the united Social-Democratic organisation in June.

The proximity of the front to a large degree determined the nature of the work of the Minsk Committee of the Bolshevik Party. It organised special courses to train propagandists for work among the soldiers. Propaganda work in the army was conducted by tried and experienced Bolshevik revolutionaries. Frequent visits to the front were made by Mikhail Vasilyevich Frunze, who had taken part in the 1905 Revolution, during which he had been active in organising combat groups. He had been twice sentenced to death for the part he had taken in the fight against the tsarist autocracy. During the war he was employed in Minsk as a clerk in the office of the Union of Zemstvos and Cities under the assumed name of “Mikhailov.” Here he formed an underground Bolshevik organisation and after the overthrow of the autocracy he became one of the principal leaders of the revolutionary movement in Byelorussia and on the Western Front, where he was extremely popular among the soldiers.

In July 1917 the Provisional Government arrested hundreds of revolutionary-minded soldiers at the front and had them brought to Minsk. The Minsk prison was overcrowded, and all the guardrooms, several army barracks, and even the Girls’ High School in the city were filled with soldiers under arrest.

The conditions of the prison were very bad and the men were kept on a starvation diet. The Minsk Committee of the Bolshevik Party formed a Political Red Cross Society for the relief of the arrested soldiers. Assistance was also rendered by the Petrograd workers, who sent the prisoners money and food parcels.

The Minsk Committee assigned to a group of comrades the task of conducting work among the soldier prisoners. In the dimly lit crowded cells, these Bolshevik propagandists would explain to the men the aims of the war, how it affected the peasants, and in whose interests it was being waged. The soldiers eagerly listened to the Bolsheviks, bombarded them with questions and asked for literature.

Soon a number of the imprisoned soldiers began to sympathise with the Bolsheviks, and a Bolshevik Party organisation was formed in the prison.

All the arrested soldiers were formed into a regiment which elected all its officers, from the regimental commander down to the corporals.

The detention prison was guarded by the 37th Regiment, in which Bolshevik influence was very strong. The guards permitted the prisoners to roam freely about the town, and the Minsk Committee of the Bolshevik Party utilised many of them as propagandists at the front. They formed groups of five or ten men, each headed by a Bolshevik, and supplied them with literature. Having been in the firing line themselves, these men knew how to approach the men in the trenches. Evading the patrols who were guarding the roads to the front, they reached the trenches and outposts where they distributed Bolshevik literature and supplemented the rousing calls of the Party with their own plain and simple talks to the men.

An important role in the work of the Minsk Party organisation was played by the Bolshevik newspaper Zvezda (The Star) which began publication at the end of July.

The initiative in publishing this paper was taken by A. F. Myasnikov, one of the outstanding leaders of the Bolshevik Party in Byelorussia. Owing to lack of funds with which to start the paper the Minsk Committee organised a lottery and a collection, but this did not bring in enough. Comrade Myasnikov himself later on related the following:

“We had no funds, so we scraped together our last copecks and sent a comrade to the Central Committee in Petrograd with a petition for a loan of a small sum of money with which to launch our literary undertaking. Although very hopeful, we nevertheless doubted whether the Central Committee would heed the request of our young and little known organisation. But our envoy returned with 2,000 rubles. We were overjoyed. With this money we could publish six issues of our daily newspaper.”[1]

The first issue of the Minsk Zvezda appeared on July 27, and nearly every subsequent issue contained editorials by Myasnikov—writing under different noms de plume, such as “A. Martuni,” “Alyosha,” and “Bolshevik”—calling upon the workers and soldiers to prepare for the struggle.

A. F. Myasnikov was an old Bolshevik who had joined the revolutionary movement as far back as 1904. He conducted his early activities in Transcaucasia—in Nakhichevan, and later, in Baku. On the outbreak of the war he was called up for military service as a sub-lieutenant in a regiment of reserves, which was quartered in Dorogobuzh, in the Smolensk Gubernia. Calm, strong-willed and unassuming, Myasnikov was a capable organiser and soon made contact with the Bolsheviks in his regiment, organised the distribution of literature, etc.

Myasnikov was in command of a company for the training of N.C.O.’s. He formed a Bolshevik group in the company and while making no secret of his hostility towards reactionary officers, and generally keeping aloof from all the officers, he was ever on the lookout for individual revolutionaries. He used to invite men from his company to his quarters and in his cautious, skilful way, gradually turned them against the autocracy. Even when the company moved closer to regimental headquarters, Myasnikov painstakingly continued his revolutionary work. On the eve of the revolution the Bolshevik Party had 13 members in the regiment.

The newspaper edited by Myasnikov became very popular among the soldiers on the Western Front and among the workers and peasants in the region. In a message of greeting to the newspaper sent by the men in prison in the Kalanchevsky Guardroom, in Minsk, we read the following:

“Difficult is your path, dear Star, for you are a lone star in the dark firmament of reaction. . . . May your light dispel this gloom. . . . May your brilliance never fade in these sombre days.”[2]

The soldiers under detention contributed their last copecks to the newspaper, and even donated the money they received from the Petrograd workers. These donations were used to establish an “iron fund” for the newspaper, the circulation of which rose from 3,000 copies in July to 6,000 in August. The High Command of the Western Front regarded this Bolshevik newspaper as a menace. On August 22, the Commissar of this front stated in a dispatch to Petrograd.

“The Social-Democratic Party in the Minsk Soviet of Soldiers’ and Workers’ Deputies has started publishing the newspaper Zvezda which is pursuing a definitely Leninist line. I have taken measures to prevent it from reaching the front.”[3]

When Kerensky ordered the suppression of the Zvezda, the directors of the newspaper, aided by a group of young workers who were active in the Party Committee, procured a motor truck and quickly cleared out the printshop where it was printed. The type which had been set up for the next number was taken to another place so that when the authorities arrived to confiscate the copy for the newspaper they found nothing there.

The Minsk organisation, under the direction of Frunze, conducted considerable activity among the peasants.

As chief of the local militia, Mikhail Frunze spent a great deal of his time visiting the villages, where he held meetings of the peasants, had heart-to-heart talks with them, and conducted revolutionary propaganda. Among the poorer section of the rural population he found many who sympathised with Bolshevism. These he helped to organise and supplied them with literature.

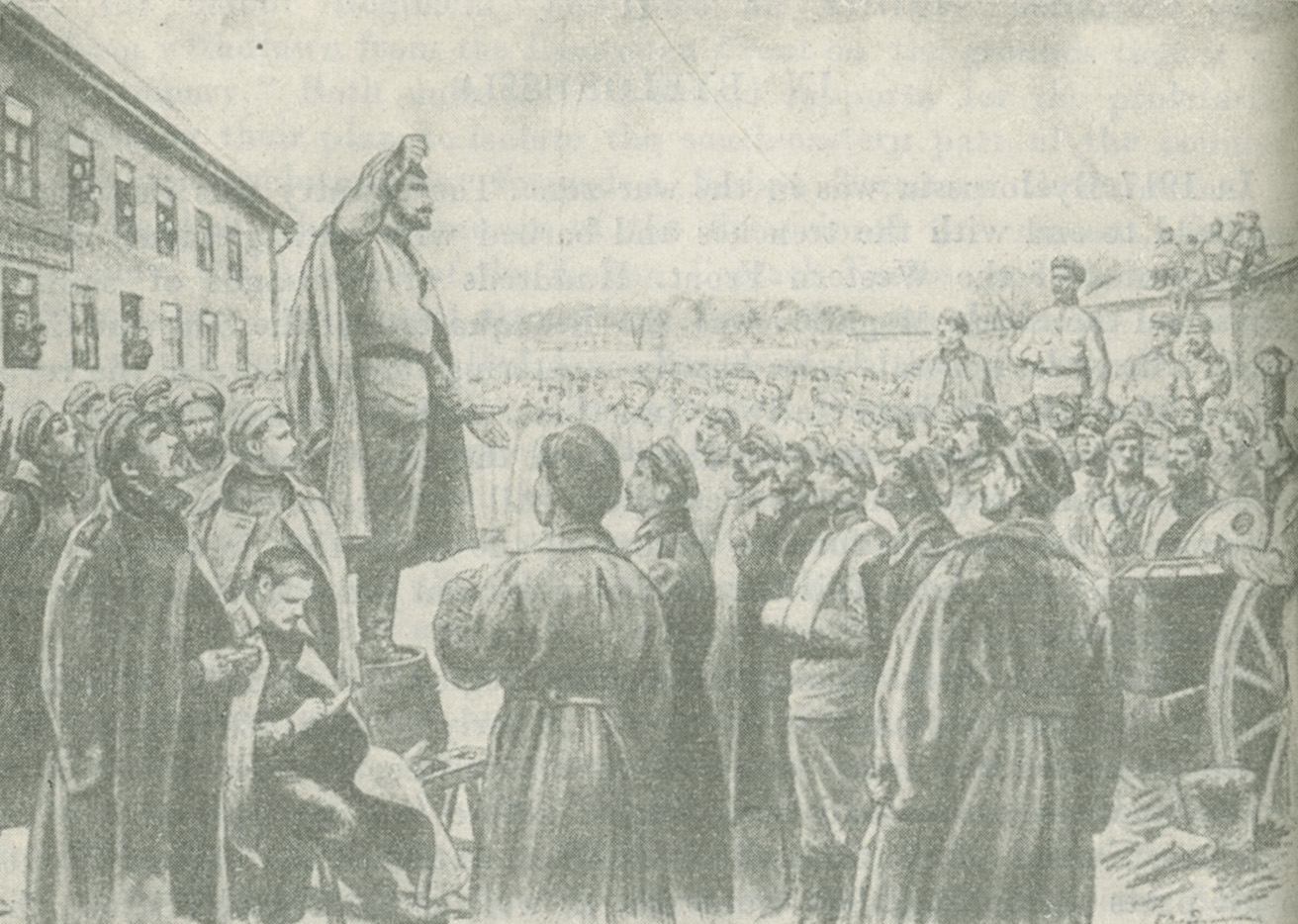

The confidence which the peasants reposed in the Bolshevik Party was strikingly manifested at the Second Congress of Soviets of Peasants’ Deputies in the Minsk Gubernia which was opened in Minsk on July 30. Among the delegates there were many elderly peasants who had never been in the city before. The Congress was opened by Frunze, and it at once became evident how popular he was among them. As Zvezda reported at the time:

“The delegates paid tribute to the enormous services our Comrade Mikhailov has rendered in organising the peasants in the Minsk Gubernia. The first to organise them, he was their leader and ideological guide, and enjoyed their complete confidence. When it was moved that Comrade Mikhailov be elected chairman without discussion, the motion was greeted with unanimous applause.”[4]

The representative of the Socialist-Revolutionaries, however, protested, and said that “it would be more fitting for a Peasant Congress to have a chairman who stood under the banner of ‘Zemlya i Volya,’ i.e. of the Socialist-Revolutionaries.

This proposal evoked loud protests from the delegates. Voices were heard shouting: “Don’t elect those who refuse to give the peasants land!” The Socialist-Revolutionaries tried to intimidate the peasants by saying: “Mikhailov is a Bolshevik.” But to this the peasants retorted: “Yes, and he’s our man!”[5]

The Socialist-Revolutionary leaders exerted strenuous efforts to dissuade the peasants from electing Frunze as chairman of the Congress. They adjourned the session, held private conferences, returned and again appealed to the delegates, but the latter were adamant. Frunze was elected chairman by an overwhelming majority. In their joy, the peasant delegates surged round the Bolshevik Frunze, tossed him in the air and then carried him shoulder-high to the platform.

Almost simultaneously with the Minsk Bolsheviks, the Bolsheviks and the Internationalists in Vitebsk withdrew from the united Social-Democratic organisation. This question was discussed at a meeting held on June 20 at which 56 Bolsheviks, 28 United Internationalists and 11 Internationalist Mensheviks were present.

The comrades who took part in the discussion said that “the local Committee of the R.S.D.L.P. has gone too far to the right,” and suggested that an independent organisation of Bolsheviks and Internationalist Social-Democrats be formed.[6]

At this meeting a Provisional Committee was elected which met on July 4 jointly with the Committee of the Lettish Social-Democratic Party. It was agreed that a common City Committee of the Bolshevik Party should be formed.

The Bolsheviks in Byelorussia were able to put their organisation and solidarity to the test during the Kornilov mutiny. In Minsk a Revolutionary Committee of the Western Front was formed. Frunze was appointed Chief of Staff of the revolutionary troops who were ready to defend the revolution.

The Minsk garrison was ready for action and was only waiting for the word of command.

The Bolsheviks in the Vitebsk Soviet formed a Military Revolutionary Bureau and representatives of the Soviet were assigned to the railway stations, the Post Office and the Staff Headquarters Telegraph Office.

In Orsha, fighting detachments were formed and were ready to go into action against Kornilov.

In Moghilev, the centre of the Kornilov conspiracy, the Soviet ceased to exist for a time. At a secret meeting of Bolsheviks held to discuss the situation, it was decided to issue a manifesto to the people in order to let the workers and soldiers and also the counter-revolutionary generals know that a revolutionary party was in existence in the city. This manifesto was secretly printed in one of the local printing plants.

Several of the workers who printed the manifesto were arrested.

In Gomel an “Emergency Committee of Five” was formed on the initiative of the Bolsheviks. The Polessye Committee sent Bolshevik Commissars to the most important points in the city, such as the post and telegraph offices. It arrested Zavoiko, General Kornilov’s “ideological adviser” and sent a number of comrades to Minsk, Rechitsa and Orsha for liaison purposes.

The fight against the Kornilov mutiny served to raise the prestige of the Bolshevik organisation in Gomel very considerably. The effect of this was immediately seen in the change that took place in the relation of forces in the Gomel Soviet, where the compromisers had predominated up to that time.

The Chairman of the Gomel Soviet was a Menshevik named Sevruk. He called himself a Bolshevik, but as early as March 1917 he spoke as a Menshevik-Defencist at the All-Russian Conference of Soviets. For this he was expelled from the Bolshevik Party, a fact which he concealed on his return to Gomel from Petrograd.

The Soviet of which Sevruk was Chairman persecuted the Bolsheviks in Gomel.

On September 1, a regular meeting of the Gomel Soviet was held at which the current situation in general, and the Democratic Conference in particular, were discussed. Thanks to the influence of the Bolsheviks, the Soviet rejected a resolution proposed by the compromising presidium in favour of uniting all the “virile forces of the country.” Another meeting of the Soviet was held on September 9 at which the question of the Democratic Conference was again discussed. The debate was opened by Sevruk.

At the end of his speech he moved the same resolution that had been rejected at the previous meeting. The Bolsheviks again secured its rejection. Having been defeated twice, Sevruk was obliged to resign the chairmanship of the Soviet.

On the election of a new presidium a Bolshevik was chosen as vice-chairman.

After the Kornilov mutiny new Bolshevik organisations arose in Rogachev, Klintsy and Dvinsk. In September, a Bolshevik organisation was definitely formed in Orsha.

An important part in the activities of the Party organisation in Orsha was played by the veteran Bolshevik, P. N. Lepeshinsky, a former high school teacher, who was extremely popular in the city. He was the Chairman of the City Duma and took an active part in the work of the Bolshevik Committee. He addressed numerous meetings and held heated debates with the Menshevik leaders who visited Orsha. In September the well-known Menshevik Lieber came to Orsha to deliver a lecture. The Bolsheviks prepared for the meeting and mobilised all their sympathisers. Lepeshinsky took part in the debate and his speech was greeted with enthusiastic applause. At the end of the debate a resolution was passed demanding the transfer of all power to the Soviets.

The revival of the organisation which had been suppressed on July 3-5 was reported to the Vitebsk Committee by the Bolsheviks of Polotsk. In October the Polotsk organisation already had a membership of about 75.

Party work was conducted on a wide scale in the armies on the Western Front. On September 9 the Bolsheviks in the 3rd Siberian Army Corps reported to the Central Committee as follows:

“We are going ahead forming new and strengthening and expanding existing Party groups. . . . At present we have in the corps 14 groups with an aggregate membership of about 1,000.”[7]

In the hectic days of preparation for the assault, scores and hundreds of new fighters for the revolution joined the Bolshevik organisations. Every day workers and soldiers came to the Party offices to enrol in the ranks of the militant Leninist Party. In August, in Vitebsk alone, 212 new members joined the Party. In September the figure rose to 353 and in October to 735.

In September the Party in Byelorussia had a total of over 9,000 members and sympathisers.

The Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party devoted considerable attention to Byelorussia. It sent organisers there and gave the Party organisations detailed instructions concerning their activities. Sverdlov often summoned the leaders of the Byelorussian Bolsheviks to Petrograd and kept them closely informed of the Central Committee’s plans and directions. He also gave practical advice to the local organisations in Byelorussia. On one occasion he wrote to the Bolsheviks in Orsha as follows:

“At the present time, no honest Internationalist can remain in a bloc with the Defencists, who by their compromising policy are betraying the revolution. . . .”[8]

The Central Committee attached special importance to the Party work in the army. In this letter Sverdlov wrote:

“In building up the military organisation you must bear in mind that it must be closely connected with the workers’ organisations. Owing to its class character, the personnel of the military organisation is not very susceptible to the ideas of proletarian Socialism. Close contact with the workers is therefore extremely important.”[9]

The best way to secure this close contact between the workers and the soldiers was to have one organisation for the region and the front.

The formation of this regional organisation was undertaken by the Minsk Committee of the Bolshevik Party. It issued notices to the Bolsheviks of Vitebsk, Polotsk, Moghilev, Gomel, Bobruisk, Slutsk, Borisov, and other towns calling a Regional Conference for September 1. It was also arranged to call a conference of Bolsheviks at the front.

Owing to the Kornilov mutiny, however, it was impossible to withdraw large Bolshevik forces from the districts with the result that only 46 delegates with the right of voice and vote and six only with the right to speak arrived in Minsk on September 1. It was therefore decided to postpone the Conference and instead to hold a council to hear reports from the districts and a review of the current situation, to discuss the rules of the Party military organisation, and to fix another date for the Regional Conference.

The deliberations of the council drew to a close on September 3 after the election of a Regional Bureau. The Regional Conference was fixed for September 15 to be held in Minsk.

How closely the Central Committee watched the process of building up this regional Party organisation may be judged from the letter Sverdlov addressed to the Bolsheviks in the 3rd Army Corps in the course of which he wrote:

“It is a very good thing that the regional organisation has become a fact. Although always important, it is particularly important at the present time, the more so that the groups belonging to it are scattered in different places.”[10]

The Regional Conference of the Bolsheviks of Byelorussia took place on the appointed date and was attended by 88 delegates—61 from the army and 27 from the region.

The first item on the agenda was: the persecution of the Bolsheviks.

The resolution that was adopted on this question demanded free speech, freedom of the press and assembly, the creation of conditions that would ensure a really free political contest, the cessation of the persecution of the Bolsheviks, the dropping of all cases of legal prosecution of a political character, the immediate liberation of all those under arrest, and amnesty for all those who had been convicted.

The Conference expressed the opinion that these measures could be achieved only if power were taken out of the hands of the imperialist bourgeoisie and transferred to the proletariat and the poor sections of the peasantry.

The delegates reported on the enormous growth of Bolshevik influence among the masses. Nearly everywhere the garrisons had become Bolshevik. The Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks were isolated. Combat groups were being formed in the regiments at the front for the purpose of fighting the counter-revolution.

A report on the current situation was made by Comrade Myasnikov, and in the resolution which the Conference adopted on his report it emphasised that:

“. . . The only organised centres in the revolutionary country are the Soviets, and they have become such to an increasing degree. . . . The Soviets are becoming stronger, the proletariat and the soldiers, the majority of whom are already conscious of their own interests and the interests of the revolution, are strengthening the Soviets. In many places the Soviets are taking power. . . .”[11]

Every line of this resolution, and every deduction drawn by the Conference, reduced itself to the one slogan: “All power to the Soviets!”

On the report on the Constituent Assembly, the Conference adopted a resolution calling for the organisation of short training courses for speakers and instructors in all parts of the region and at the front where Party organisations existed, the calling of conferences in the Vitebsk and Moghilev electoral areas to nominate candidates for the Constituent Assembly, and the nomination of candidates in the Minsk electoral area.

The Conference endorsed as the official organ of the Regional Committee the newspaper Molot which had started publication on September 15 in place of Zvezda after the latter had been suppressed by the government.

Like its predecessor Molot played an important organisational role in Byelorussia and on the Western Front. Officers sent telegram after telegram to Headquarters complaining about the newspaper. At last, on October 3, General Vyrubov, Chief of Staff of the Supreme High Command, sent the following message to General Baluyev, Commander-in-Chief of the Western Front.

“I sent a request to have the newspaper Molot suppressed. As long as that paper circulates at the front no measures to restore order will prove effective. The Supreme Commander-in-Chief has ordered Molot to be suppressed and the printing plant to be requisitioned. A telegram to this effect has been sent to you today.”[12]

On October 6 Molot was suppressed and the printing plant at which it was printed was sealed. The military authorities had decided to raid the printing plant and place a guard over it, but the soldiers refused to perform police duty. The Minsk Soviet undertook to take care of the premises and after posting a military guard demanded that the seals be removed. This demand was supported by the entire garrison, which had expressed great indignation at the order suppressing the Bolshevik newspaper. The 289th Infantry Regiment even threatened to resort to arms.

The chief of the garrison was terrified at this and yielded to the garrison’s demand. Two days later, on October 8, a new Bolshevik newspaper, the Burevestnik was published in place of the Molot.

The voice of the Burevestnik was heard right up to the victory of the proletarian revolution. In its columns the workers and peasants, and the soldiers on the Western Front, were able to read Lenin’s articles. Issue No. 3, of October 11, contained Lenin’s article “The Crisis Has Matured,” No. 8, of October 17, contained his article “The Nationalisation of the Banks,” and Nos. 13-16, his “A Letter to Comrades.”

Lenin’s articles in the Burevestnik and his pamphlet Can the Bolsheviks Retain State Power? which the Minsk Committee reprinted, became the Bolshevik program of action in Byelorussia.

The practical results of the First Regional Conference in Byelorussia were seen in the organisation of the election campaign when the Soviets came up for re-election.

The first Soviet in Byelorussia to dissolve and appoint new elections was the Minsk Soviet, which had been under Bolshevik influence from its inception.

The Party in Minsk took advantage of the election campaign to explain the political situation in the country to the masses. Within a short period, the Minsk Committee arranged as many as 40 lectures on the current situation. The election returns showed that the people had full confidence in the Bolsheviks. In the newly elected Minsk Soviet the Bolsheviks had 184 seats, the Socialist-Revolutionaries 60, the Mensheviks 21.

The new Soviet exercised enormous influence. Throughout October it devoted its efforts to training its armed forces and collecting and taking stock of arms. The influence and prestige of the Bolshevik groups grew also in those Soviets which did not stand for election again, or in which the Bolsheviks did not succeed in obtaining a majority in the elections.

The Vitebsk Committee of the Party also paid close attention to work in the Soviet. In the latter half of September the Vitebsk Bolsheviks began to make active preparations for the Gubernia Congress of Soviets.

Fearing that the Bolsheviks would obtain a majority at the Gubernia Congress, the Menshevik and Socialist-Revolutionary leaders of the Soviet succeeded by manipulating the elections in securing the return of 300 peasant deputies and of only 40 representatives of the workers and soldiers. The Congress was opened on October 4. There were only 26 Bolsheviks present, but they had the backing of scores of other delegates. This was seen during the voting on the resolution on the current situation, when nearly one-fifth of the delegates voted against the resolution moved by the Socialist-Revolutionaries and for the resolution moved by the Bolsheviks.

Although the Bolsheviks did not yet have a majority in the Soviet, the Vitebsk Committee of the Bolshevik Party, in the middle of October, began to make active preparation for the seizure of power by the Soviets. At a meeting of the Committee held on October 20, comrades from the army units were co-opted, thus linking the Committee more closely with the masses of the armed forces. At the same meeting a military organisation was formed.

In Gomel the Bolsheviks’ struggle for influence was complicated still further by the fact that the Jewish workers in the city were imbued with nationalist ideas. There was a strong organisation of the Bund (the Jewish Social-Democratic League) in the city headed by hardened politicians who exercised considerable influence among the petty bourgeoisie. Lieber, Weinstein—the Chairman of the Central Committee of the Bund who had his headquarters in Minsk—and other leaders of the Bund often visited the city. This put the utmost strain upon the Bolshevik forces.

But already in September it was evident at the meetings that were addressed by the visiting Menshevik and Bundist leaders that the Bolsheviks had gained predominance.

On October 5 the Second Regional Conference of Bolshevik organisations in Byelorussia and on the Western Front was opened in Minsk. The brief minutes of this Conference that have been preserved tell us very little about the great work carried on by the Bolshevik organisations in the short period between the First and the Second Conferences. The most eloquent testimony of this are the figures showing the growth of the Party membership. During the 20 days that passed between the two conferences, the Party organisation in Byelorussia increased almost sixfold. At the Second Conference 28,591 members and 27,856 sympathisers were represented. At the time of the First Conference the army organisation on the Western Front had a total of 6,500 members and sympathisers, whereas at the time of the Second Conference the figure had risen to 49,000. At the time of the First Conference the civilian organisations had 2,642 members and sympathisers. Twenty days later the figure stood at 7,453.

The Conference, which was opened by Comrade Myasnikov, who was elected chairman, sent greetings to Lenin.

On the question of the Soviet and Army Committee elections, the Conference instructed the different organisations:

“To exert all efforts to ensure in the districts the convocation of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’, Soldiers’ and Peasants’ Deputies on the appointed date—October 20.”[13]

It also instructed them to see to it that the newly elected army committees should send to the Congress of Soviets representatives who will “express the will and defend the interests of the working people.”[14]

The Byelorussian organisations quite rightly regarded the struggle for the early convocation of the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets as one of their fundamental tasks.

In accordance with the decision of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party of September 24 concerning the holding of Regional Congresses of Soviets, for the purpose of preparing for the All-Russian Congress of Soviets, a Regional Conference of Soviets was held in Minsk on October 16.

The overwhelming majority of the delegates at this conference were Bolsheviks. In its resolution the conference associated itself with the manifesto issued by the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region calling for the convocation of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets and insisted that this Congress should be convened not later than October 20.

On October 22 the Minsk Soviet celebrated the 12th anniversary of the formation of the St. Petersburg Soviet. Comrade Myasnikov delivered an address on the historical significance of the St. Petersburg Soviet of 1905 and urged the necessity of seizing power by force of arms. The Soviet supported this idea in the resolution adopted after Myasnikov’s speech.

The working people of Byelorussia sent to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets 46 delegates, of whom 20 were Bolsheviks and six “Left” Socialist-Revolutionaries. Nearly all the delegates received instructions to support the transfer of all power to the Soviets.

The delegates of the Minsk, Gomel, Vitebsk, Gorodoksk, Nesvizh, Slutsk, Rechitsa and Orsha City Soviets, and the Soviets of the Tenth Army, the Guards Corps, the 35th Army Corps and the 37th Infantry Regiment conveyed to the Congress of Soviets the demand of their people for “All power to the Soviets.” The delegates of only three Soviets, i.e., the Vitebsk Gubernia Soviet, the Moghilev City Soviet and the Orsha District Soviet, which were still under the influence of the compromisers, came to the Congress with the demand for “All power to democracy.”

On the eve of October, the Bolsheviks had torn Byelorussia from the enemy’s grasp and had converted it into a stronghold of the revolution.

[1] A. Myasnikov, “Preparations for October,” Balshavik Belarusi, 1927, No. 3, p. 33.

[2] “Greetings to Zvezda from Arrested Soldiers,” Zvezda (The Star), Minsk, No. 3, August 1, 1917.

[3] Central Archives of Military History, File No. 185, folios 57-60.

[4] “Report on the Second Peasants’ Congress Held in Minsk on July 30, 1917,” Zvezda, Minsk, No. 6, August 6, 1917.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Byelorussian Party Archives, Fund 640, File No. 1063, folio 1.

[7] The Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute. Excerpts from Correspondence between the Bolshevik Organisations in Byelorussia and on the Western Front and the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.), No. 1108.

[8] Ibid., No. 1111.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., No. 1108.

[11] The C.P.(B.) of Byelorussia in Resolutions, Part I (1903-1921), Party Publishers, Minsk, 1934, p. 60.

[12] Central Archives of Military History, File Nos. 155-109 and 515.

[13] The C.P.(B.) of Byelorussia in Resolutions, Part I, (1903-1921), Party Publishers, Minsk, 1934, p. 71.

[14] Ibid.

Previous: In the North Caucasus

Next: The Baltic Provinces