Vance Archive | Trotskyist Writers Index | ETOL Main Page

Walter J. Oakes, Toward a Permanent War Economy?, Politics, February 1944.

Transcribed by Ernest Haberkern (Center for Socialist History, Berkeley, California).

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

As this article goes to press, the Wall Street Journal of Jan. 6 carries a lead story which strikingly confirms one of Mr. Oakes’ main points: the scope of the planning now going on for World War III. The Journal’s Washington correspondent writes: The State Department is now considering a big post-armistice stockpile scheme. Under this proposal, which has now reached Secretary Condell Hull, the Government would accumulate a hoard of strategic materials, mostly from imports, over a period of some five years after the war. Goods like crude rubber and industrial diamonds would be stored above ground in warehouses; commodities such as tin and petroleum would be amassed below ground in vaults, mines and subterranean reservoirs. Such a program, say its advocates, would provide a hedge against any future national ‘emergency’ (presumably, the next war). In addition, it would provide a balance for the large-scale American export program that is in prospect for world reconstruction, offering a way for debtor nations to repay public loans advanced by this country. The Journal also reports that Vice-Chairman Batt of the War Production Board, speaking the same day in Chicago, urged adoption of a similar plan. Indicating the idea has had “more than casual official consideration”, Batt suggested it as “a novel means of approaching a balance in our foreign trade picture”. This last argument shows the intimate connection that is coming to exist between war-making and economic stability. The riddle of how the impoverished, relatively backward rest of the world is going to pay for American exports of goods and capital, is neatly solved by importing vast quantities of raw materials and “sterilizing” them, much as the gold at Fort Knox is sterilized, by burying them in stockpiles withdrawn from the market. War and the prospect of war offer the means for performing this useful economic trick. In war modern capitalism has, as this article shows, an economic stabilizer better than pyramids, cathedrals and WPA rolled into one. – Ed. Politics, 1944. |

AS World War II enters its climactic stage, it becomes increasingly clear that this is not the “War To End All Wars.” Already there have been many warnings of the “possibility of another war.” A growing cynicism is abroad concerning the prospects of durable peace. World War III is not only a distinct possibility, it is inevitable as long as the world’s social structure remains one of capitalist imperialism. As Dorothy Thompson puts it in her column of December 6, 1943, “All grand alliances (referring to the Roosevelt-Stalin-Churchill meeting), have existed only as long as it was necessary to win a war, or protect themselves against the aggressions of other powers. Once all enemies are defeated, the only potential enemies left are members of the grand alliance themselves.” In more scientific terms – the contradictions which led to this war have not been eliminated: if anything, they have been intensified.

More revealing than any theoretical analysis concerning its inevitability are the obvious preparations that are now being made for World War III. One may dismiss the psychological preparations, designed to condition the population to accept the inevitability of the next war, as too intangible to evaluate. One may shrug aside the political preparations, which are clearly inherent in the power politics now being played by the leaders of the United Nations, on the ground that this is realpolitik in a materialistic world. But it is impossible to overlook the unanimity with which the business community approves the maintenance of a large standing army, universal military service and an air force second to none as preconditions of America’s “security” in the post-war world. Disarmament, the utopian pipedream of Geneva, is to be abandoned as a slogan after this war – except for the conquered enemy.

Important as are the above more or less obvious types of preparation, currently concealed economic preparations are decisive. In the United States, this question is intimately bound up with the problems of reconversion. Much more is at stake than the question of what to do with the huge government-owned war plants (estimated at $20 billion by the end of the war). A plan for reconversion, no matter how loose and flexible, must be guided by some Indication of the type of post-war world that is desired. If war within the life of the next generation is a probability, then it must be planned for on the basis of the lessons learned from this war.

American imperialism, for example, has no intention of entering another war without adequate stockpiles of all critical and strategic military materials. And so we have Senate Bill 1582 (introduced early in December 1943 by Senator Scrugham of Nevada) whose stated purpose is:

“To assure an adequate supply of strategic and critical minerals for any future emergency by holding intact in the post-war period all stock piles surviving the present war owned by Government agencies and by necessary augmentation thereof primarily from domestic sources.”

The “future emergency” is subsequently defined as “a total war of three years’ duration, or of any equivalent emergency.”

In the case of copper, an article in the National Industrial Conference Board’s Economic Record (November 1943) reveals what would be involved. “As current usage of copper probably is at least 1.5 million tons annually, a supply for a three-year war, as proposed in the Scrugham bill, might require 4.5 million tons. This amount is nearly equal to the entire domestic output of new copper in the Thirties, or four years’ output at the peak mining rate of 1.07 million tons in 1942.” While the Scrugham bill leaves the question of cost open, it is estimated that the copper program alone would cost well above $1 billion. Clearly, economic preparations for World War III are beyond the stage of informal discussion.

The big question which all discussions of post-war economy try to answer is, of course: How to achieve full employment? The sad experiences following the last war, culminating in the world-wide depression of the 1930s, give the problem an understandable urgency. Public interest in the question is certainly more widespread than ever before. What better tribute to American advertising genius, or what more fitting commentary on the political and economic naivete of the American people, could there be than the $50,000 contest now being held by the Pabst Brewing Company, in commemoration of its 100th birthday, for the best plans to achieve full post-war employment?

There is an urgent political necessity for capitalism to achieve the abolition of unemployment. It is motivated by the inevitable slack in private investment in order to maintain the savings-investment equilibrium.

Assuming, therefore, that my major thesis is correct and that government balancing operations in the future will consist largely of socially sanctioned war outlays, the question arises: how will the future laws of capitalist accumulation differ from the past?

In the past, the dynamics of capital accumulation have caused a polarization of classes. (On the one hand, concentration of wealth in fewer and fewer monopoly capitalists; on the other, a steady increase in the size of the working class, both factory and non-factory, relative to other classes). The war, far from interrupting, has accentuated both these trends – in general, at the expense of the middle classes.

Although this law will still hold true in the epoch of Permanent War Economy, the increased State military outlays 1 as compared with prewar State expenditures) will have the effect of slowing up the rate of class polarization. This is due not so much to the different economic nature of these expenditures as to their political character. Their purpose, it must be remembered, is to stabilize the economy; i.e., by State intervention to freeze class relations and simultaneously the existing class structure. That is why the post-war size of the labor force and the national income will be considerably below that achieved during the war. Otherwise, the magnitude of post-war war outlays would be at a level so high as virtually to guarantee widespread political opposition on the part of the capitalist class.

The major revision that will have to be made in the Marxian analysis of capitalist accumulation is in the famous law, that an increase in capital means an increase in the industrial reserve army. If the Permanent War Economy succeeds in stabilizing the economy at a high level, unemployment will be eliminated, but only through employment in lines that are economically unproductive. Thus capitalist accumulation, instead of bringing about an increase in unemployment, will have as its major consequence a decline in the standard of living.

The decline in the standard of living will be similar in nature to that which is just beginning to take place in wartime. For example, until about the middle of 1942 it was possible for the developing American war economy to support a substantial increase in military production at the same time that a small, but significant, rise occurred in average civilian standards of living. This was due, for the most part, to the fact that in 1939 there was considerable underemployment of both men and resources. Once more or less full employment was attained, however, further increases in military production could only be achieved at the expense of the civilian sector of the economy. Most civilians have not yet felt the full impact of this development because of the accumulation of huge inventories of consumers’ goods in the hands of both merchants and consumers. As these inventories are depleted and as consumers’ durable goods wear out, the standard of living begins to decline noticeably. If the war continues throughout 1944, with no significant over-all cutbacks in military programs, the decline is apt to become precipitate.

The Permanent War Economy will operate much the same way. At first, of course, there may be a rise in the average standard of living if the levels of national income reached, are reasonably close to those now maintained and if, simultaneously, there is a sharp reduction in total miiltary out lays (inclusive of expenditures for “relief and rehabilitation”). Within a relatively short periGd, however, assuming that the economy is stabilized at the desired level with a minimum of unproductive governmental expenditures, the maintenance of economic equilibrium will require a steadily rising curve of military outlays. The decline in the average standard of living of the workers, at first relative, will then become absolute – particularly on a world scale as all na. tions adapt their internal economies to conform with the requirements of the new order based on an international Permanent War Economy. Naturally, the decline will not be a descending straight line; it will have its ups and downs, but the long-term trend will definitely be downward.

Three major assumptions are implicit in the above analysis. First, any significant increases in real national income or total product beyond the reconversion equilibrium level are excluded, due to the capitalist nature of production. This ties in with the reasons why continued accumulation of capital is necessary and why these additional increments of capitalist accumulation require more or less corresponding (socially acceptable) economically unproductive State expenditures. Second, while a portion of the State’s consumption of accumulated unpaid labor may take the form of public works, for reasons previously stated only a minor portion of such public works will be capable of raising the standard of living; and these will decline in importance as direct war outlays increase. Third, the possible effects of alternative fiscal policies (financing through difference:methods of taxation and borrowing ) to support the Permanent War Economy are excluded as not affecting the basic anlysis; although certain methods may markedly accelerate the inflationary process, while others may permit American entry into World War III without having experienced a violent inflation.

Capitalist society is forever seeking a “stable and safe” equilibrium – one which eliminates unemployment or, at least, reduces it to negligible proportions (“stable”); and one which is generally acceptable or, at least, politically workable (“safe”).

This is, of course, hardly a new problem. Instability has been a dominant characteristic of capitalism particularly since technological advances in industry have become marked, a matter of some fifty to one hundred years. It is only in recent years, however, especially since the Bolshevik Revolution plainly demonstrated that capitalism is a mortal society and can be succeeded by a different set of socio-economic institutions, that the problem has taken on a new urgency. Theoretical analysis indicates, and the observations of capitalists confirm, that capitalism would have great difficulty in surviving a depression comparable in severity to the recent one. This must be avoided at all costs, say the more enlightened members of the bourgeoisie, even if far-reaching structural changes are called for. True, this type of motivation has led to fascism and can easily do :so again. It is assumed, however, that the ruling class prefers to stave off the advent of fascism as long as possible, and that there is sufficient evidence to indicate that what I have termed “a Permanent War Economy” is coming to be a much more powerful stimulus than the increasingly-repeated question: “If we can employ everyone in wartime, why can’t we do as much in peacetime?” The fact is that the capitalist system cannot stand the strain of another siege of unemployment comparable. to 1930-1940. It does not require a far-seeing statesman to picture the revolutionary dynamite inherent in a situation where 10-12 million people are unemployed. And this is a conservative estimate of the size of post-war unemployment, if the traditional methods, such as those used after the last war, are followed this time.

The traditonial methods (consisting essentially of trying to restore the status quo ante bellum as rapidly as possible) will not be followed. Whether Roosevelt presides over the transition period or not, too much water has flowed under the bridge to permit an uncontrolled post-war inflation followed by a resounding and catastrophic depression. This much, at least, the better minds amongst the capitalists see. The State will have to intervene. It is a question of how much and in what form.

Here we encounter a problem in semantics. State intervention, as I shall show below, must take the form of maintaining a Permanent War Economy. What is a “war economy”? In an extreme sense, involving the reduction of civilian standards of living to the bedrock minimum in order to permit the maximum expansion of war output, we have not, of course, a war economy today. Russia, since the consolidation of Stalin’s dictatorship, and Germany, since the consolidation of Hitler’s dictatorship, both in “peace” and in the period of military hostilities, have experienced this type of war economy. They are the only countries in modern times to have experienced a “genuine” war economy, with the possible exception of Japan.

A war economy, as I use the term, is not determined by the expenditure of a given percentage of a nation’s resources and productive energies for military purposes. This determines only the kind of war economy – good, bad, or indifferent from the point of view of efficiency in war-making. The question of amount, however, is obviously relevant. At all times, there are some expenditures for war or “national defense.” How much must the government spend for, such purposes before we can say a war economy exists? In general terms, the problem can be answered as follows: a war economy exists whenever the government’s expenditures for war (or “national defense”) become a legitimate and significant end-purpose of economic activity. The degree of war expenditures required before such activities become significant obviously varies with the size and composition of the national income and the stock of accumulated capital. Nevertheless, the problem is capable of theoretical analysis and statistical measurement.

Until the present period, in America at least, only one legitimate end-purpose of economic activity has been recognized (in theory) ; namely, the satisfaction of human wants or, less euphemistically, the production and distribution of consumers’ goods and services. In wartime, of course, the legitimacy of war expenditures is never questioned, except by those few who question the progressiveness of the aims of the war. We are now being prepared, however, to recognize as a legitimate economic activity peacetime expenditures for war of a sizable nature. Hereinis lies the real importance of the psychological preparations now under way for World War III.

The state will have to spend for war purposes as much as is required to maintain a “stable and safe” equilibrium. As a result, unemployment will be a thing of the past. Barring the immediate outbreak of World War III – i.e., within five years of the end of World War II – the size of post-war war outlays is not significantly influenced by the potential utility of such expenditures for war-making. The decisive consideration is the level of employment that it is desired to maintain. Based on preliminary estimates of national income and capital accumulation in the interim period between World War II and World War III, the United States will achieve a Permanent War Economy through annual war expenditures of from $10-20 billion. Thus, the inner functioning of American capitalism will have been significantly altered, with profound consequences for all classes of society.

Why these “balancing” expenditures on the part of government must take the form of war outlays rather than public works requires a brief excursion into the past history of unpaid (surplus) labor.

The root of all economic difficulties in a class society lies in the fact that the ruling class appropriates (in accordance with the particular laws of motion of the given society) a portion of the labor expended by the working class or classes in the form of unpaid labor. The expropriation of this surplus labor presents its own set of problems; generally, however, they do not become crucial for the ruling class until the point is reached where it is necessary to pile up accumulations of unpaid labor. When these accumulations in turn beget new accumulations, then the stage of “primitive accumulation” (designed to build up the physical stock of the country for immediate consumption’ rose purposes) ceases and the stability of the society is threatened. The ruling class is impaled on the horns of a most deep serious dilemma: to allow these growing and mature accumulations to enter into economic circulation means to undermine the very foundations of existing society (in modern terms, depression); to reduce or eliminate these expanding accumulations of unpaid labor requires the ruling class or sections of it to commit hara-kiri (in modern terms, the capitalist must cease being a capitalist or enter into bankruptcy). The latter solution is like asking capitalists to accept a 3 per cent rate of profit, because if they make 6 or 10 per cent they upset the applecart and destroy the economic equilibrium. This is too perturbing a prospect; consequently, society as a whole must suffer the fate of economic disequilibrium unless the ruling class can bring its State to intervene in such a manner as to resolve this basic dilemma.

Since a class society can support on a relatively stabled it basis a certain amount of accumulated unpaid labor, the problem becomes one of immobilizing the excess. State intervention is required precisely because no individual member of the ruling class will voluntarily give up the opportunity to accumulate further wealth. The State, therefore, acts in the interests of all the members of the ruling class; the disposition of the excess accumulated unpaid labor is socially acceptable, and generally unnoticed by individual members of the ruling class.

Such, for example, was the role performed by pyramid-building in Ancient Egypt, the classic example of a stable economy based on the institution of chattel slavery. In feudal society, based on the accumulation of unpaid labor through the institution of serfdom, an analogous role was performed by the building of elaborate monasteries and shrines. These lavish medieval churches were far more than centers of worship and learning, or even than examples of conspicuous expenditure on the part of the ruling classes; they were an outlet for the unpaid labor of feudal society – an outlet which permitted a deadening economic equilibrium for centuries.

Capitalist society, of course, has had its own pyramids. These ostentatious expenditures, however, have failed to keep pace with the accumulation of capital. In recent times, the best examples have been the public works program of the New Deal and the road building program of Nazi Germany. Both have been accomplished through what is termed “deficit financing.” That is, the state has borrowed capital (accumulated surplus labor for which there is no opportunity for profitable private investment) and consumed it by employing a portion of the unemployed millions, thus achieving a rough but temporarily workable equilibrium.

While the Roosevelt and Hitler prewar “recovery” programs had much in common, there is an important difference. The latter was clearly a military program; all state expenditures were calculated with a direct military use in view. As such, they did not, for the most part, conflict with the direct interests of the capitalist class of Germany who wished to reserve for private capital all opportunities for profitable investment. In the United States, only a minor portion of the WPA and PWA programs possessed potential military usefulness. Consequently, as such expenditures increased, the opposition of the capitalist class rose (this was basically an economic development, although the psychological impetus afforded by recovery from the depths of depression undoubtedly aided the process). The more money the state spent, the more these expenditures circumscribed and limited the opportunity for profitable private investment. The New Deal was dead before the war; the war merely resuscitated its political expression and was, in reality, an historical necessity.

War expenditures accomplish the same purpose as public works, but in a manner that is decidedly more effective and more acceptable (from the capitalist point of view).

In this, capitalism is again borrowing from the techniques employed by the more static class societies of slavery and projects were officially counted among the unemployed. Today, however, not only are those engaged in producing the instruments of war considered to be gainfully employed; even those in the armed forces are classified as part of the employed labor force. It is only necessary to perpetuate into the post-war period this type of bookkeeping which classifies soldiers and munitions workers as “employed,” and then war (“national defense”) outlays become a legitimate end-purpose of economic activity; a Permanent War Economy is established and socially sanctioned; capitalist society is safely maintained – until the next war.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of capitalist society – in comparison with earlier class societies, and at the same time that which indicates its superiority over these earlier forms – is the rapidity with which wealth is accumulated. Alternating periods of rising and falling business activity have resulted and have come to be accepted as an inevitable and peculiarly capitalist feature of the accumulation of capital. This was, at least, the situation prior to World War II. To understand the basic laws of motion of capitalist society required the application of the fundamental Marxian concepts of the increasingly high organic composition of capital and the falling average rate of profit. With these tools Marx predicted, and one could analyze, the results of capitalist accumulation. The Marxian general law of capitalist accumulation may, for convenience, be expressed as two laws; namely, the inevitable tendencies toward the polarization of classes and the increase in unemployment.

Today, however, this analysis no longer holds good without certain modifications. The new element in the situation is clearly the fact that the entire present period (in the United States, beginning with the advent of the Roosevelt Administration) is one of increasing State intervention. New forces are set in motion and new laws or trends are discernible. The war both obscures and highlights these basic changes in the functioning of capitalism. The role of the State is obviously increased, but the conduct of the war gives rise to the illusion that this is a temporary affair. But the government cannot spend upwards of $300 billion on war expenditures, acquiring ownership of huge quantities of facilities, raw materials and fabricated goods, without having a profound and lasting effect on the body economic. How to dispose of an anticipated $75 billion of government assets at the end of the war is one of the more perplexing questions troubling the best minds among the bourgeoisie today.

If the Republicans are victorious in the 1944 elections, it is conceivable that they might try to restore the status quo ante bellum. Reversing an economic trend, however, is far more difficult than reversing a political trend. Destroying or immobilizing $75 billion of government assets is qualitatively a different proposition than the situation which existed at the end of World War I. It would be impossible to do this, and at the same time to maintain employment at a high level and to carry through the international plans of American imperialism. Any such Republican experiment will necessarily be short-lived. As for the Roosevelt Administration – it seems to be “sold” on the Keynesian proposition that public investment must take up the inevitable slack in private investment in order to maintain the savings-investment equilibrium.

Assuming, therefore, that my major thesis is correct and that government balancing operations in the future will consist largely of socially sanctioned war outlays, the question arises: how will the future laws of capitalist accumulation differ from the past?

In the past, the dynamics of capital accumulation have caused a polarization of classes. (On the one hand, concentration of wealth in fewer and fewer monopoly capitalists; on the other, a steady increase in the size of the working class, both factory and non-factory, relative to other classes). The war, far from interrupting, has accentuated both these trends – in general, at the expense of the middle classes.

Although this law will still hold true in the epoch of Permanent War Economy, the increased State military outlays i as compared with prewar State expenditures) will have the effect of slowing up the rate of class polarization. This is due not so much to the different economic nature of these expenditures as to their political character. Their purpose, it must be remembered, is to stabilize the economy; i.e., by State intervention to freeze class relations and simultaneously the existing class structure. That is why the post-war size of the labor force and the national income will be considerably below that achieved during the war. Otherwise, the magnitude of post-war war outlays would be at a level so high as virtually to guarantee widespread political opposition on the part of the capitalist class.

The major revision that will have to be made in the Marxian analysis of capitalist accumulation is in the famous law that an increase in capital means an increase in the industrial reserve army. If the Permanent War Economy succeeds in stabilizing the economy at a high level, unemployment will be eliminated, but only through employment in lines that are economically unproductive. Thus capitalist accumulation, instead of bringing about an increase in unemployment, will have as its major consequence a decline in the standard of living.

The decline in the standard of living will be similar in nature to that which is just beginning to take place in wartime. For example, until about the middle of 1942 it was possible for the developing American war economy to support a substantial increase in military production at the same time that a small, but significant, rise occurred in average civilian standards of living. This was due, for the most part, to the fact that in 1939 there was considerable underemployment of both men and resources. Once more or less full employment was attained, however, further increases in military production could only be achieved at the expense of the civilian sector of the economy. Most civilians have not yet felt the full impact of this development because of the accumulation of huge inventories of consumers’ goods in the hands of both merchants and consumers. As these inventories are depleted and as consumers’ durable goods wear out, the standard of living begins to decline noticeably. If the war continues throughout 1944, with no significant over-all cutbacks in military programs, the decline is apt to become precipitate.

The Permanent War Economy will operate much the same way. At first, of course, there may be a rise in the average standard of living if the levels of national income reached are reasonably close to those now maintained and if, simultaneously, there is a sharp reduction in total miiltary outlays (inclusive of expenditures for “relief and rehabilitation”). Within a relatively short peric,d, however, assuming that the economy is stabilized at the desired level with a minimum of unproductive governmental expenditures, the maintenance of economic equilibrium will require a steadily rising curve of military outlays. The decline in the average standard of living of the workers, at first relative, will then ] become absolute – particularly on a world scale as all nations adapt their internal economies to conform with the I requirements of the new order based on an international Permanent War Economy. Naturally, the decline will not i be a descending straight line; it will have its ups and downs, but the long-term trend will definitely be downward.

Three major assumptions are implicit in the above analysis. First, any significant increases in real national income or total product beyond the reconversion equilibrium level are excluded, due to the capitalist nature of production. This ties in with the reasons why continued accumulation of capital is necessary and why these additional increments of capitalist accumulation require more or less corresponding (socially acceptable) economically unproductive State expenditures. Second, while a portion of the US State’s consumption of accumulated unpaid labor may take the form of public works, for reasons previously stated only a minor portion of such public works will be capable of raising the standard of living: and these will decline in importance as direct war outlays increase. Third, the possible effects of alternative fiscal policies (financing through difference methods of taxation and borrowing) to support the Permanent War Economy are excluded as not affecting the basic anlysis; although certain methods may markedly accelerate the inflationary process, while others may permit American entry into World War III without having experienced a violent inflation.

Capitalist society is forever seeking a “stable and safe” equilibrium – one which eliminates unemployment or, at least, reduces it to negligible proportions (“stable”) ; and one which is generally acceptable or, at least, politically workable (“safe”).

This is, of course, hardly a new problem. Instability has been a dominant characteristic of capitalism particularly since technological advances in industry have become marked, a matter of some fifty to one hundred years. It is only in recent years, however, especially since the Bolshevik Revolution plainly demonstrated that capitalism is a mortal society and can be succeeded by a different set of socio-economic institutions, that the problem has taken on a new urgency. Theoretical analysis indicates, and the observations of capitalists confirm, that capitalism would have great difficulty in surviving a depression comparable in severity to the recent one. This must be avoided at all costs, say the more enlightened members of the bourgeoisie, even if far-reaching structural changes are called for. True, this type of motivation has led to fascism and can easily do again. It is assumed, however, that the ruling class preftts to stave off the advent of fascism as long as possible, and that there is sufficient evidence to indicate that what I have termed “a Permanent War Economy” is coming to be regarded as a feasible, even if temporary, alternative to fascism.

How will the Permanent War Economy operate? Can it achieve the “stable and safe” equilibrium? It is possible to chart the major outlines of the functioning of the Permanent War Economy. The assumptions underlying this projection are listed below in outline form without any attempt at justification. They are grouped under three broad headings, as follows:

MILITARY

INTERNATIONAL

DOMESTIC ECONOMY

(all dollar figures in 1943 prices)

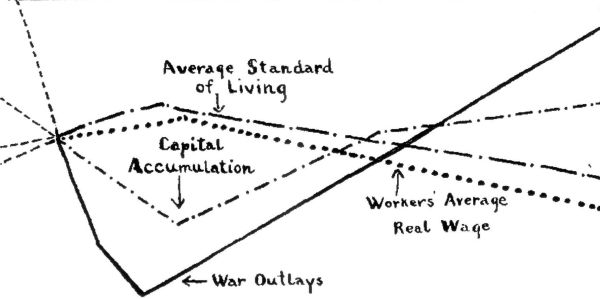

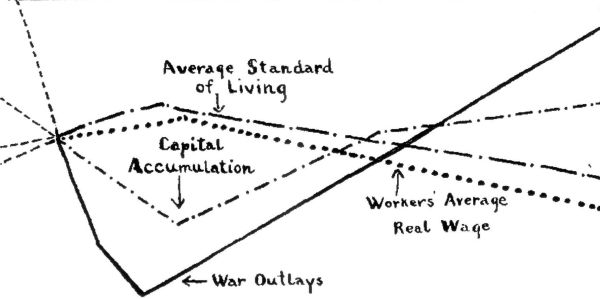

On the basis of these assumptions, the table below of the movement of capital accumulation, government war outlays, the average standard of living and average real wages of the working class ander the Permanent War Economy follows logically.

1947 is chosen as the base year, for this is assumed to be the first “normal” post-war year. 1946 is considered as a year of transition. The concepts are presented in index ambers in order to show bask trends under the Permanent War Economy. Thus, according to the chart, the critical period will be 1934–1936. It Is at this time that the inherent contradictions of capitalism will begin to threaten seriously the newly-found economic stability, pushing society rapidly in the direction of World War

|

Minor divergences will not materially affect the validity of the assumptions. This is particularly true of assumptions 1–9 and 17–20, which are really political and economic generalizations. For example, the analysis still holds true even World War III should take place in 1965 or 1970, rather than, as predicted, in 1960. Assumptions 10–16 are of a an entirely different character. Here, substantial differences in magnitude might render the forecasts useless. But 12, 13, 14 and 16 require explanation. The others conform rather closely to most predictions now being made.

The figure stated in assumption 12, taken together with that stated in assumption 13, is only slightly above the estimate made by Professor Alvin Hansen (one of the outstanding authorities in this country on the theoretical aspects of investment policy) of $20–25 billion as the amount necessary to be invested in the post-war period. The level indicated have would be $30 billion, hardly a significant difference. Assumption 13 provides for private capital formation is perfectly consistent wih the hest prewar years starting with the history of capitalism since it entered the phase of permanent crisis.

Assumption 14 will appear very high to those who view the post-war situation in the same manner as the prewar situation. An interesting confirmation of the estimate made here appears in the October 1943 issue of the National Industrial Conference Board’s Economic Record in an article entitled Postwar Budget Prospects: 1945–1948:

While all the figures for future years are necessarily speculative, they are particularly so for national defense expanditures in the post-war period. Armed forces numberimg 1 million lee would constitute a smaller number than are assionsed in some quarters. If the size of the armed services should be nearer to 2 million, expenditures of about $7 billion would seem to be more nearly the level of our peacetime defense expenditures than the $4 billion shown for l948. The natureand the extent of equipment that would be used by our armed forces in the post-war era could account for variations in expenditures of several billion dollars a year. (My italics – W.J.O.)

A total military establishment of 2 million appears to be conservative in the light of plans for occupation and policing forces, plus conscription of the youth. Equipment and supplies for this size military force should easily reach $10 billion. Stockpiling and other military outlays, direct and indirect, appear to be quite capable of raising the total to $20 billion, the upper limit in the assumption.

The average of current estimates regarding the probable size of the post-war labor force is about 55 million persons. Assumption 16, therefore, is considerably below prevailing estimates; for if the difference of 5 million were to constitute unemployment in any genuine sense of the term, it is obvious that the Permanent War Economy would not be, fulfilling its main function. 50 million is a more realistic figure than 55. It is higher than all prewar records, although it is some 13 million below the current peak o about 63 million (which includes those in the armed forces) The translation of those in the armed forces into active members of the labor force, is subject to shrinkage which depending on battle casualties and related factors, should run between 1 and 2 millions. Net retirements, due to the excess of over-age people leaving jobs as compared with new entrants, should be close to 3 million. The balance of 8 million represents women who are temporary war worker and are expected to leave the employed labor force once the war is over. This figure includes current child labor and is therefore not much higher than generally accepted “guess-timates.”

The assumptions upon which the operations of the Permanent War Economy are predicated thus appear to be realistic. Among the many problems which will remainare two outstanding and closely related ones: can class relations be frozen, and can disastrous inflation be prevented. Each requires a separate article, to be adequately discussed. The first, as I have indicated, is directly related to the pre cess of capitalist accumulation in the post-war period.

It depends not only on many political factors but on severa economic ones, the most important of which is clearly the question of inflation.

It is not my belief that the Permanent War Economy wit provide an enduring solution for capitalism. But it can work for the period under consideration; and there is like wise no reason why appropriate fiscal policies (from the point of view of the capitalists, which means anti-working class in essence) will not be successful in preventing out right inflation. The national debt, astronomical as it mar seem, presents no serious problem. Assuming an annual interest burden of $7 billion, a very generous estimate, this will easily be covered out of current tax receipts. It is the type, as well as the amount, of taxes to be levied that will constitute one of the major areas of political and class conflict. The question is made still more acute by the fact that inflation appears to offer the bourgeoisie an easy way out to unload the cost of the war onto the backs of the working masses of the population. A policy of this kind however, cannot be drifted into; it must be adopted consciously. If the die is now, or soon to be, cast in favor of deliberate and uncontrolled inflation, this can only mean that the decisive section of the ruling class is determined to establish fascism as soon as possible. I see no evidence at present, to warrant this belief although, of course, there are many similarities between fascism and the Permanent War Economy. The danger of inflation is not diminished by a Permanent War Economy; on the contrary, it is steadily increased. But it seems more probable that the inflation-fascism sequence is a contender for a prime place on the agenda after World War III than in the post-World War II period.

It is not likely that the above analysis, necessarily presented in sketchy, outline form, will meet with any enthusiastic reception. For one thing, it runs counter to all currently organized and clearly defined bodies of political thought. Orthodox Marxists (Trotskyists) have convinced themselves that only a successful proletarian revolution can end this war; otherwise fascism will rule the post-war world. New Dealers want to restore “free competition” and make capitalism humane; the only practical note amidst their absurdities is the attempt to win a fourth term for Roosevelt. Social Democrats are still for socialism in theory and capitalism in practice. In fact, all capitalist (and Stalinist) political thought will deny the possibility of a Permanent War Economy, although they will support measures leading toward its establishment.

Moreover, the imagination, courage and capacity of the human mind to project itself forward in an hour of deep social crisis and deal with reality instead of illusion has not been a very noticeable characteristic of the human species. Nevertheless, this war, which has already destroyed so many cherished illusions, will destroy many more before it is consigned to the history texts. The drift of events is toward a Permanent War Economy. What better solution has capitalism to offer? And what likelihood of an anti-capitalist solution is there at present? What may now seem fantastic to many will, as the present war draws to a close, appear to be obvious as the evidence piles up.

Upon the shoulders of the labor movement rests the real responsibility for preventing World War III. This universally-approved objective can never be achieved by the Roosevelts, Churchills, Stalins, or Chiang Kai-Sheks of this or the next decade. For the labor movement, especially its socialist-minded sector, to stand a chance to prevent the atomization of society as a result of repeated wars requires much closer and more realistic study of what is actually happening in the world today than has yet been evidenced. The basic strategic aim of socialism as the only rational alternative to capitalism needs no revision except that of modernization. It is in the field of tactics that substantial revisions are needed. A declining standard of living under a Permanent War Economy cannot be successfully fought by a labor movement whose most powerful organizations are trade unions, no matter how powerful these may be. The important battle areas will be abstruse (to the masses) economic questions, such as the size and composition of the Federal budget, taxation and fiscal policy, investment alternatives, and the like, rather than wages, profits and working conditions for specific industries or factories. These latter will still be important, to be sure, but they will largely be determined by the decisions affecting the former. This points to the necessity not only of widespread mass economic education, but of the vital need for an independent political Party of labor. Only a labor party, independent of capitalist political machines, and based upon trade unionists, is capable of coping with the problems of living under a permanent war economy.

Vance Archive | Trotskyist Writers Index | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 16 August 2019