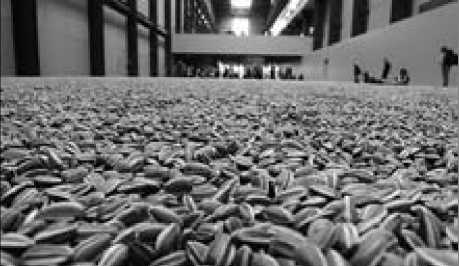

Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds in Turbine Hall, 2010

John Molyneux Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Irish Marxist Review, Vol. 8 No. 28, June 2020, pp. 60–70.

Copyright © Irish Marxist Review.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

|

This article is an extract from Chapter 2 of my forthcoming book The Dialectics of Art, due to be published by Haymarket in December 2020. Between the first section of the article, which discusses the social structures through which aesthetic judgments are made, and the second section, which advances a Marxist perspective, the book contains an extensive discussion of the various criteria (mimesis, skill, beauty, the sublime, emotional power and expression, realism, ethics/morality/politics, originality, and critique) that have been used historically to evaluate visual art, and argues that in practice judgments tend to be based on an unsystematic amalgam of these criteria.

|

Let us start with the fact that judgment is more or less inescapable. Some people may profess themselves uninterested in this question, but in practice most people, including those who deny it and including those whose interest in visual art is minimal, do make some judgments of the merits of various artworks. Even the statement ‘I don’t know much about art but I know what I like’ is a judgment of sorts. And regardless of what individuals do, it is clear that society as a whole has no choice but to make a series of such assessments. Far more art is produced than is going to survive, so decisions have to be made as to what will be preserved and what will be discarded and destroyed. Within what is preserved, another multitude of decisions arise as to what will be displayed and where. Which works will hang in the Louvre or the Uffizi? Which statues will be placed in the main square or in front of the presidential palace? Which examples will be featured in the art books? Which artists merit monographs? Which works and which artists will feature in the educational curriculums and the slideshows of professors? Which will be bought and sold by dealers and collectors, and at what prices?

And if judgment is unavoidable, this raises the questions of how the judgment is made, by whom, and on the basis of which criteria. This chapter is predominantly concerned with the third of these questions, but I will start by saying something about the first two. The process of judgment is often imagined by people to be largely personal or individual, but this is not really so. Just as people often tell themselves that the clothes they wear are a purely personal decision when in fact it is heavily determined by quite strict social norms, occupational rules, dress codes, fashion, and all sorts of social influences, so it is with art.

Both the average person and the so-called art lover are heavily influenced by what they have heard and read. They don’t stand in front of a painting they’ve been told is by van Gogh and look at it with the same eyes as they look at one by an unknown artist. This applies just as strongly, perhaps even more so, to ‘the expert’ – the art historian or professional critic – on whom there is social pressure to ‘appreciate’ the Vermeer, whereas the layperson might just say, ‘It does nothing for me’.

Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds in Turbine Hall, 2010

|

So the judgment of art is a social process. It operates through a range of institutions and strategically placed individuals within those institutions. The process changes over time. It was not at all the same in the Renaissance as it was in nineteenth-century France or is in the world today. No judgment is wholly innocent, original, or final. Whereas in fourteenth-century Florence or eighteenth-century Russia the process may have been relatively simple and transparent, involving a small number of readily identifiable aristocrats, royals, popes, and burghers, it is now highly complex and, in a sense, mysterious.

One reason it seems mysterious is that it involves the art market, which works, to a considerable extent, anonymously. Another reason is that many of the key decisions are made in secret and never publicly explained. If the Tate Modern decides to commission a work for its Turbine Hall or hold a ‘blockbuster’ exhibition for a certain artist, this will undoubtedly boost that artist’s reputation. But why that artist is chosen and not another – why Ai Weiwei and not Tracey Emin, or why Joan Miró and not Salvador Dalí – need never be publicly articulated. Then there is the fact that the process is simultaneously national, continental, and global, with different judgments made at different levels. Jack Yeats is ‘big’ in Ireland, with a room dedicated to his work in the National Gallery, but he is little celebrated in Europe or the United States and almost unknown in India or China. Very few artists have generated truly global reputations, and, for obvious historical reasons, they have been overwhelmingly European.

Jack Yeats, The Liffey Swim, 1921

|

Another point that needs to be made is that judgments are not unanimous. There is no absolute consensus. I have known seriously engaged and knowledgeable ‘art world’ people who thought Michelangelo vastly overrated or totally disparaged Francis Bacon. [1] Salvador Dalí and David Hockney are both ‘popular’ and ‘successful’, especially in market terms [2], but would be less highly rated by scholarly opinion. The same divergence would be even more the case with the work of Jack Vettriano. However, the absence of absolute consensus does not render the collective judgments of the ‘art world’ and its key players ineffectual. On the contrary, they have real social and economic force.

Jack Vettriano, The Singing Butler, 1992

|

When it comes to the operation of the art world to-day [3], it is possible to identify the following actors in the formation of aesthetic judgments: critics (journalistic and academic), historians, museum and gallery directors and curators, dealers, collectors, the art-engaged public, and artists themselves. Obviously the identification of their relative influence cannot be an exact science, though it might make an interesting ethnographic study. In the absence of that, I’m merely offering some impressionistic observations which may, however, be useful.

Of the categories listed, the critics may appear to play the central role, especially because their judgments are public. But in my view their influence is generally overrated. Much more important are museum directors, dealers, and, above all, collectors: they have much greater institutional and economic power, and we should not ignore the extent to which the critics actually depend on them, economically and culturally, rather than shape them. Here we should note that most of the ruling class (the bourgeoisie) do not concern themselves much with visual art, and certainly not in any serious way, but they are aware of its cultural significance and either ‘delegate’ some of their number to ensure their overall hegemony in this field (as in all fields of cultural life) or select certain people as their trusted intermediaries.

The role of big capitalists – the Rockefellers, Whitneys, Guggenheims, Gettys, and so on – in promoting ‘modern’ art is indisputable, and we know that the CIA consciously intervened to deploy abstract expressionism as an ideological weapon in the Cold War [4] (a manoeuvre which also had the effect of raising the movement’s aesthetic standing). Check out the patrons of any major gallery and one will see a list of big corporations and significant members of the bourgeoisie. At certain moments in time, it is possible to identify particular individuals as having exceptional influence: Alfred H. Barr Jr. at MoMA in the 1930s; Clement Greenberg as ‘top’ U.S. critic in the fifties and sixties, along with Kenneth Clark in Britain; Charles Saatchi and Nicholas Serota in the nineties. But none of them stood alone or were unchallengeable. Behind Barr was the Rockefeller family, and he was sacked as MoMA Director in 1943 by a businessman, Stephen Carlton Clark of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, who was chairman of MoMA’s board of trustees. Greenberg was rivalled as a critic by Harold Rosenberg, and his influence waned dramatically as art changed in a direction Greenberg had not foreseen.

|

The role of ‘the public’ should also be mentioned here. Of course, the public is not undifferentiated. There are vast swathes of the world’s population who take little or no interest in the art world and whose influence on the process of aesthetic evaluation is close to zero. But even if we restrict consideration to those who visit museums and galleries, purchase art books and reproductions, and so on, their influence on critical judgment is small. Their lack of funds prevents them having any serious weight in the art market, and they have almost no institutional mechanisms (except via attendance figures at exhibitions) for expressing their views. Most of the time they are far more influenced by art world ‘movers and shakers’ than they are influencing. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to discount the art-engaged public altogether. For example, Tracey Emin’s intense popularity with a certain layer (mainly of young women) has, I think, had an influence on directors and critics (see the discussion of Emin later in this book).

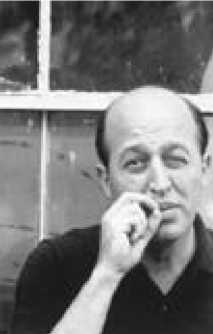

William Adolphe Bougereau, The Nympheam, 1878

|

Finally, we should consider the influence of artists themselves. Again, this cannot possibly be measured in any way exactly, but when we look at art history it would appear to have been a factor. Many times the leading artists of a period have gravitated to each other’s company, in Montmartre or Soho or the Cedar Tavern. In Florence, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were rivals, knowing each other to be the key players. In Paris in 1906, the same seems to have applied to Picasso and Matisse. In London in the fifties it was Bacon and Freud, and in the late eighties, Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas, Tracey Emin, et al. They, the artists themselves, probably have the clearest idea out of any of the groups listed as to who are the best artists of their time, and their opinions do have an impact on wider aesthetic tastes. The reason they have an effect is that although it is ultimately the bourgeoisie (or its cultural wing) who have the most influence on the establishment of the art canon (past and present), as part of their overall project of class hegemony, they nevertheless want to do so on the basis of hegemonising great art and great artists, rather than promoting the merely second- and third-rate. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the bourgeoisie and aristocracy made historical fools of themselves by backing the wrong horse, by supporting the academic art of the Salon against the emerging avant-garde – for instance, William-Adolphe Bouguereau versus Paul Cezanne. They, the more intelligent ones at least, do not wish to repeat this error. Therefore they need to find out what should be considered good, which they learn, at least in part, from artists whose company they cultivate.

At this point I want to move beyond the sociology of aesthetic evaluation to the criteria on which it can be based. Here I propose to look first at the main criteria which have been used, and are used today, to make judgments of quality. I will then look at what Marxism has to add to this conversation, in the process shifting from a consideration of how judgments are actually made to how I think they should be made.

I want to turn to what I see as the specifically Marxist contribution to this question. I use the word contribution rather than ‘theory of’ because I think it builds upon and adds to all the criteria developed over the centuries that we have been discussing, rather than replacing them. As my examples would indicate, I accept that these criteria, inherited from the past, have been and can be used to make valid and effective aesthetic judgments. However, I am now shifting to considering how I think we, as Marxists, should assess art – not just how people actually do assess it. But I do so on the understanding that while these Marxist assessments may differ from what might be considered the traditional academic or bourgeois canon, this will certainly not be the case in every instance. In other words, we should not expect that because mainstream art history approves of Piero della Francesca, Velazquez, and Rembrandt, Marxist art history will reject them.

This will not be a survey of the views of Marxists who have contributed to the question of aesthetic value: even naming them produces an excessively long list. [5] I will first deal briefly with the question of politics and art, and even more briefly, once again with ‘realism’, and then set out my own view.

Paul Cezanne, Les Grandes Baigneuses,

|

It is widely assumed that Marxism advocates and entails the assessment of an artwork’s merit, mainly or partly, on the basis of its politics. As literary critic Stuart Sim puts it, ‘Marxism is the prime example of a politically motivated aesthetic theory’, and ‘underneath both crude and sophisticated Marxism lies a similar compulsion to situate artworks within a political context ... Art’s value to a Marxist, therefore, is to be politically determined.’ [6] Sim, in his essay, repeats this idea on numerous occasions – but this does not make it true. The ‘therefore’ in the above sentence is especially illegitimate in that it does not follow from ‘situating art in a political context’ that its value is ‘politically determined’. But there is more involved here than that particular piece of poor logic.

Certainly it is true that for Marxism art is ultimately subject to assessment by political criteria, but, and this is crucial, only in the final analysis; it is the case only in the sense that everything – food, medicine, science, sport, all human activities – are subject to politics, because politics is about the general governance of human society, and (Marxist) politics is about the survival and liberation of humanity. This does not mean that Marxists can or should judge whether or not della Francesca’s The Baptism of Christ or Bacon’s Screaming Pope is a good painting by either the political views of the artist or what we deem to be the political/ideological message expressed in the painting.

Some care is needed to explain precisely what I mean here. I do not mean that some works of art are ‘non-political’ or non-ideological. All works, without exception, exist in a social, ideological, and political context, and are permeated by ideology; and all ideology is political in the broad sense. Nor do I mean that the analysis of works of art should ignore their ideological and political content, focussing only on their ‘form’. I mean that a Marxist cannot read off the aesthetic evaluation of a work on the basis of the extent to which that work’s worldview is ‘progressive’, ‘radical’, or corresponds to Marxism.

In the seventeenth century, Rubens was the principal artist of the Catholic/aristocratic counter-revolution, and this profoundly shaped the form and content of his work. But this does not mean that Marxists can, on this account, write him off or deny his greatness as an artist. His work displays far too many outstanding qualities for that, and part of his greatness was precisely the skill and elan with which he expressed the outlook and visual sensibility of that counter-revolution compared to numerous mediocre works of the day. Another example would be George Grosz, who was a member of the Communist Party of Germany (when it was a revolutionary socialist organisation, not yet corrupted by Stalinism), and whose work was explicitly anti-capitalist, predominantly comprising savage attacks on the German bourgeoisie. It does not follow from this that for a Marxist, Grosz is a greater artist than, say, the much less radical Matisse or Mondrian. It is possible to argue that the greatness or merits of an artist’s work are damaged or limited by the artist’s ideological standpoint, but this argument has to be made concretely and demonstrated in the work; it cannot be read off or assumed. [7]

Of course, it must be recognised that many would-be or self-proclaimed Marxists have attempted or even insisted on the mechanical application of political criteria to art. Mainly, if not exclusively, this is associated with Stalinism in its various forms [8], but it was not the practice of the classical Marxism of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky, Luxemburg, and Gramsci, to which I adhere, or of most serious Marxist art historians and critics. The most well-rehearsed examples are Marx’s advocacy of the conservative Balzac (along with Aeschylus, Shakespeare, and the like) and Trotsky’s polemics on this question in the early years of the Russian Revolution.

To identify the distinctive Marxist contribution to aesthetic evaluation, we have first to go back to basics. According to historical materialism, art is a component of the superstructure that arises on, and is conditioned by, the economic base which comprises the forces and relations of production. In his 1859 preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, Marx wrote:

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. [9]

Speaking at Marx’s graveside, Engels restated, as he did on many occasions, this basic idea:

Just as Darwin discovered the law of development or organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of development of human history: the simple fact, hitherto concealed by an overgrowth of ideology, that mankind must first of all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, before it can pursue politics, science, art, religion, etc.; that therefore the production of the immediate material means, and consequently the degree of economic development attained by a given people or during a given epoch, form the foundation upon which the state institutions, the legal conceptions, art, and even the ideas on religion, of the people concerned have been evolved, and in the light of which they must, therefore, be explained, instead of vice versa, as had hitherto been the case. [10]

The truth of the proposition that art is ‘conditioned’ by the economic base of society, its forces and relations of production, is, I think, obvious. The art of the Paleolithic, of the Middle Ages, of the Renaissance, of nineteenth-century Europe, and of the twenty-first century is hugely different, and much of this difference is accounted for by the fact that Paleolithic society rested on stone tools and cooperative foraging, that of the Middle Ages on agriculture and feudal land ownership, and nineteenth-century Europe on industrial capitalism and wage labour; and today, we live with globalised late capitalism in decay. The art of da Vinci, Michelangelo, or Rembrandt would have been literally impossible in the Paleolithic or even the early Middle Ages, and that of Tracey Emin and Ai Weiwei equally impossible in the nineteenth or even early twentieth century. Of course, the relationship between base and superstructure is not mechanical or automatic. As Engels put it:

Peter Paul Rubens, The Judgment of Paris, 1636

|

We regard the economic conditions as conditioning, in the last instance, historical development ... The political, legal, philosophical, religious, literary, artistic, etc., development rest upon the economic. But they all react upon one another and upon the economic base. It is not the case that the economic situation is the cause, alone active, and everything else only a passive effect. Rather there is a reciprocal interaction with a fundamental economic necessity which in the last instance always asserts itself. [11]

But, even with Engels’s proviso, there is more to be said when it comes to understanding and judging art. The core social relations of production (slave owner and slave, lord and peasant, capitalist and worker) generate and are surrounded by a host of other social relations: between monarchs and subjects, husbands and wives, lovers, children, and parents, brothers and sisters, masters and servants, bartenders and customers, entertainers and audiences, officers and soldiers, judges and prisoners, prostitutes and clients, popes, priests, and their flock, almost ad infinitum; they also generate a no-less-extensive set of social relations between people and things and people and nature; people and their food and drink, their houses, their other possessions, their animals, their land, their transport, the mountains, the sea, the trees, flowers, and sky. These relations are just as much social relations, ever-changing, and products of historical development as the relations between people. A hunter-gatherer and an eighteenth-century squire do not have the same relationship to a horse or a bull. The different meaning of trees to Hobbema, van Gogh, and Mondrian is as much a social change as the difference between Titian’s and Manet’s views of a courtesan/prostitute.

George Grosz, Toads of Property, 1921

|

These social relations occupy a social space, as it were, between the economic base and the political and ideological superstructure, and they are shaped by both in an ongoing dialectical interaction. Moreover, they are the stuff of art. By this I mean not only that art depicts these relations, which it does a great deal of the time, but also that it expresses them and responds to them. The last point is important. Because art, as I argued in the previous chapter, is a product of creative human labour, it constitutes not just a passive reflection of social relations but an active, sometimes positive, sometimes negative, response to them. There are times when this is starkly obvious – van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait or Hals’s group portraits of the Regents and Regentesses of the Old Men’s Almshouse or Leger’s Cyclists or Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans; other times it is much more indirect – a Constable landscape, a Turner storm, a Mondrian abstract, Emin’s My Bed. But always the expression and response to social relations is there, and always it constitutes the core, the animating spirit of a significant work of art.

Here we have a further and overarching criterion for the evaluation of art, and one that is distinctively Marxist in that historical materialism offers the most convincing and effective basis for the analysis and understanding of social relations.

Hans Holbein, Henry VIII, 1540

|

Works of art are good or great insofar as, and tot he degree that, they give powerful and insightful expression to social relations and, especially, to new and changing social relations. Other criteria I have considered here – mimesis, technical skill, beauty, emotional power, realism and so on – are not negated or replaced by this criterion but subsumed under it. They become possible means – each important in its own right – to achieving a unity of content and form through which the powerful expression of social relations is achieved.

All the critical essays that follow in the body of this book argue this case in relation to their respective subjects – from Michelangelo to Yasser Alwan – but for the sake of clarity I will give some examples here.

Holbein’s Henry VIII is a great portrait not simply because it achieves an accurate likeness (we assume) or because it deploys immense technical skill in the rendering of attire, but because these and other qualities, for example the composition, all combine to achieve a powerful representation of what it meant to be an absolute monarch in the sixteenth century, to have the power of life and death over not only his wives but over everyone in the kingdom. Absolute monarchy, of course, is not a quality that inheres in the personality of the individual ruler but is a condensation of class and social relations; and this portrait expresses brilliantly the relationship between the king and his subjects. The same general point can be made about other great portraits, such as Bellini’s Portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan and Velazquez’ Portrait of Pope Innocent X or, obviously in a different way, van Gogh’s Portrait of Postman Joseph Roulin.

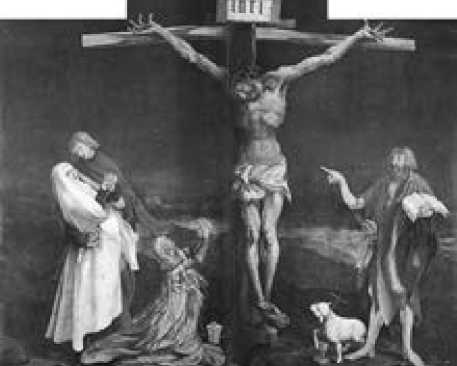

Grunewald’s Crucifixion powerfully evokes the suffering of Christ on the cross in a way that distinguishes it from the numerous Renaissance, mannerist, or Baroque crucifixions. But this is an expression of the more personal and intimate view of the relationship between the individual and God that was a key element in the Protestant Reformation, which was in turn a reflection of new ‘bourgeois’ social relations arising with the first stirrings of capitalism.

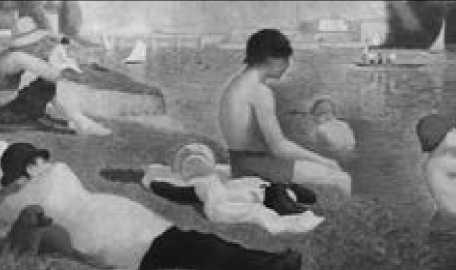

Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières is one of the greatest paintings of the nineteenth century because of its originality in combining with fine compositional and painterly skill the achievements of Manet and impressionism to give pictorial expression to a new social relation: the emergence and ‘solidification’ of a factory proletariat. [12] It was the combination of this content and this form, classical and monumental, that made the painting so initially unacceptable.

In this context I want to mention one of John Berger’s finest essays, The Moment of Cubism (which builds on his analysis in The Success and Failure of Picasso), in which he demonstrates how the development of cubism was a response to the massive transformation in social relations in the specific conjuncture of Europe before the First World War. This is an exceptionally rich example of the kind of Marxist analysis I am advocating.

Mathias Grunewald, Crucifixion, c.1515

|

Mondrian’s trademark abstracts of the twenties and thirties – compositions with blocks of primary colours within a grid of black lines on a white or pale background – are great works not because (as he himself imagined) they express fundamental natural or mystical forces, but because they are a response to a ‘pure’ aesthetic distillation of one aspect of the modern city environment – the bourgeois city of steel, glass, and straight lines – hence their affinity with Bauhaus and modernist design and architecture. His Broadway Boogie Woogie builds on this work, but moves beyond it, in response to the experience of the dynamism and energy of Manhattan skyscrapers, automobiles, and street life. [13]

It is clearly necessary that this approach should work not only for demonstrating the merits of various works and artists, but also for making comparative and negative judgments – that is, for explaining why other works and artists are much less good. Compare, for example, the French Academy nudes of the nineteenth century such as the Birth of Venus, or paintings by Alexandre Cabanel and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, with Manet’s contemporary Le Dejeuner sur l’Herbe and Olympia. It is not just that Manet is undoubtedly original and ‘critical’ in formal terms; it is that Manet gives expression to important developments in social relations in a way that is absent from Cabanel and Bouguereau, whose works tell us nothing about lived and changing social experience, other than constituting ‘evidence’ of the persistence of a lazy and familiar sexism.

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884

|

Two other examples I would give are Salvador Dalí and Anish Kapoor. Dalí is one of the most famous painters of the twentieth century, and certainly the most famous surrealist, but his art, despite its mimetic surface facility within fairly conventional naturalist representation (of ‘surrealistic’ fantasy scenes), says little or nothing of power or insight about mid-twentieth-century social relations. Essentially, it is superficial sensationalism. Anish Kapoor is much less meretricious, but most of his work, while visually attractive, consists primarily of mere visual tricks and effects. It expresses nothing significant about social relations and is therefore not significant or important art.

Henry Moore, Family Group, 1946

|

There are many other comparisons we can make using this approach. Compare the sculpture of Henry Moore and Alberto Giacometti – two very important artists of the mid-twentieth century. Moore is certainly highly skilled and probably more ‘beautiful’ than Giacometti, but which artist’s work speaks more powerfully and profoundly to the social relations of the age? In my view the answer would be Giacometti. His art expresses with great intensity the individual isolation and alienation of human beings under capitalism. True, it is a one-sided expression – for there is much more to contemporary social relations than isolation and alien-ation – but in art, intense one-sided insight is more valuable than well-balanced but shallow reflection. By contrast, Moore, for all his formal power, offers uncritical expression of conventional social relations (principally of the nuclear family) and tries to render them profound by ‘naturalising’ them. To me this makes Giacometti the greater artist.

Alberto Giacometti. Standing Woman, 1956–7

|

Now let us look at Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. There are obvious parallels between the work of these two artists, who hailed from the same time and place and knew and painted each other. [14] I would rank Freud higher than Bacon in terms of technical skill, realism, and psychological insight, but whose work makes the more powerful statement about human social relations in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? In my view the answer is Bacon, which is why, without in any way dismissing Freud (whom I admire), I would consider Bacon the greater artist.

Finally, this Marxist criterion is highly appropriate for assessing the recent work of relational art, participatory art, and ‘the social turn’ – more appropriate, at any rate, than criteria which focus on qualities inhering in the art ‘object’, such as mimesis, harmonious beauty, or even realism. Nicolas Bourriaud famously defined relational aesthetics and art as ‘a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space’. [15] What I am saying is that, ultimately, all aesthetics should be ‘relational aesthetics’ (albeit not in the narrow sense of involving audience interaction) and that, again ultimately, the same standard applies for judging the Mona Lisa and Guernica as for Carsten Holler’s Test Site.

Carsten Holler, Test Site, 2006

|

Holler’s Test Site was an installation in the huge Turbine Hall space of the Tate Modern in 2006. It consisted of five massive metal tubes or slides stretching from the upper floors to ground level, which visitors were invited to use. One of the key characteristics of relational art is that the viewer is asked to participate in the work, and their participation ‘completes’, as it were, its making. In this respect Test Site is exemplary. But how can it be evaluated aesthetically?

Holler called his work ‘a sculpture that you can travel inside’ but maintained it could be observed as a sculpture in its own right without sliding down it. In this respect it is possible to assess it in terms of all the different criteria outlined earlier in this chapter – its technical skill, beauty, sublimity, emotive power, and so on. However, his main pitch was that it offers, to those who take the slide, ‘a device for experiencing an emotional state that is a unique condition somewhere between delight and madness’. [16] It is also possible to see the work as ‘art critical’ in that it critiques and challenges the traditional space of the gallery as highly elitist, stuffy, silent or temple-like, and certainly makes it more child friendly. [17] But to what extent and how powerfully does Test Site express and respond to social relations in the wider society? It can be reasonably argued that the work offers an implicit critique of existing (alienated, utilitarian, commodified) social relations by evoking and involving people in the experience of ‘utopian’ relations of play, conviviality, pleasure, and so on.

Thus, on all these grounds, Test Site can be considered a work of some merit, but the merit, in my judgment, is limited. As sculpture it is not outstanding (compared say to that of Brancusi, whom Holler references), nor especially beautiful, sublime, or emotionally powerful, and the same could be said of the ‘experience’ it offers the participant. The critique of the gallery space is valid and useful, but the critique of wider social relations is indeed utopian and rather lightweight, bland even; and this points to an objection that can be made to much of the relational art championed by Bourriaud.

The question of relational art – how it has developed further and been further politicised in ‘the social turn’ – will be taken up again in the final chapter. At this stage, however, I have demonstrated how the criteria of aesthetic evaluation we have been considering are and can be deployed, especially within a historical materialist framework, to assess art across its full range, at least in the Western tradition. [18]

1. This was the original position, later revised, of John Berger, who compared Bacon not to Goya but to Walt Disney. See John Berger, Francis Bacon and Walt Disney, in John Berger: Selected Essays, Geoff Dyer (ed.), (London: Bloomsbury, 2001), 315.

2. Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) is, at the time of writing, expected to sell at auction for $80 million, the highest price for a living artist.

3. I am here essentially speaking about the Western art world (i.e., North America and Europe). In a sense, this is not just limited but also wrong in that in that the art world in the twenty-first century has gone global in a way that was never the case before, particularly with the inclusion of China. I return to his point in chapter 11.

4. See Eva Cockcroft, Abstract Expressionism: Weapon of the Cold War, in Artforum, Summer 1974, https://www.artforum.com/print/197406/abstract-expressionism-weapon-of-the-cold-war-38017.

5. For example: Plekhanov, Raphael, Antal, Hauser, Trotsky, Lukacs, Benjamin, Brecht, Adorno, Caudwell, Klingender, Zhdanov, Sartre, Althusser, Macherey, Berger, Jameson, Hadjinicolaou, Lindsay, Clarke, Rifkin, Eagleton, Harrison, Wood, Edwards, Roberts, Duncan, Hemingway, and many others.

6. Stuart Sim, Marxism and Aesthetics, in Philosophical Aesthetics: An Introduction, Oswald Hanfling (ed.) (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995), 441–43.

7. I have made such an argument in relation to Rubens, where I suggest that, in comparison to Rembrandt, much of his work – though superb in many respects – is diminished in its depth and sensitivity by the sociopolitical nature of his clientele.

8. The high, or low, point was reached with Stalin’s cultural supremo, A.A. Zhdanov, though a similar approach was adopted by Maoism, especially during the Cultural Revolution.

9. Karl Marx, Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy, in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Selected Works, vol. 1 (Moscow: Foreign Languages Press, 1962), 361.

10. Frederick Engels, ‘Speech at the Grave of Karl Marx’, 17 March, 1883, Highgate Cemetery, London, available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1883/death/burial.htm.

11. Frederick Engels, Letter to H. Starkenburg (1884), in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Selected Works, vol. 2 (Moscow: Foreign Languages Press, 1962), 504.

12. See Mike Davis, Old Gods, New Enigmas (London and New York: Verso, 2018), 42–43.

13. There is an interesting comparison to be made between Mondrian’s late work and the work of Robert Rauschenberg as representations of ‘the city’.

14. They were subjects of a joint exhibition, All too Human, at the Tate Britain in 2018. Exhibition guide available at https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/exhibition/all-too-human.

15. Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon: Les Presses du reel, 2002), 113.

16. Carsten Holler, interview by Vincent Honore (2006), Tate Modern official website, https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/uni-lever-series/unilever-series-carsten-holler-test-site/carsten.

17. I regard this as a significant plus and one that has been built on and extended by work such as Superflex’s One, Two, Swing installation of a brightly coloured, child-friendly surface on the entry ramp leading to numerous swings, also in the Turbine Hall, in 2017–18.

18. For clarity I should say that I am not maintaining that Marxism applies only to Western art. Historical materialism is a theory of world history, and the idea that ‘great’ art captures social relations should apply to the art of many cultures, but I have only demonstrated this in relation to the Western art due to my greater familiarity with that tradition.

John Molyneux Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 1 January 2023