Peter Green Archive | ETOL Main Page

From International Socialism 2 : 21, Autumn 1983, pp. 3–57.

Transcribed by Marven James Scott.

Marked up by Einde O’ Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Few crises have been so widely predicted as the international banking crisis which finally hit the headlines in August 1982. [1] But such predictions merely testified to the impotence of the actors in the saga to govern their own destiny. The actions of the bankers themselves nearly brought disaster down upon their own heads; yet they had merely been pursuing the quest for profits, a quest dictated not so much by their own greed (although they are certainly greedy men) as by the fundamental nature of capitalism as a competitive system.

When Mexico in August 1982 declared that it could not pay its debts, the only novelty was that those debts amounted to anything between 80 and 90 billion (thousand million) dollars. The world’s biggest debtor had gone bust and the prospect of the banks getting their money back was in the opinion of many experts, nil. Yet the Mexican crisis was only the culmination of a series of defaults (although nobody liked to call them that), of failures to pay what was owed to the various creditors, by nation-states, stretching back over the previous eight years.

In 1975 North Korea refused to pay its debts, which were mainly to other governments. In 1977 both Peru and Zaire had to be rescued by the International Monetary Fund after failing to meet their payments to the banks on several billion dollars worth of debt. In 1979 Turkey and Zaire once more, had to have their debts rescheduled (i.e. the date of re-payment was postponed, although they were expected to go on paying interest for the banks). [2] In 1981, Poland, with debts of 24 billion dollars, sent a shudder through Western banking circles as its economy collapsed, and the struggle between the regime and the working-class organised in Solidarity remained deadlocked. In each case, the banks emerged a trifle shaken but with their profit figures still looking rather healthy. Each crisis was more serious than the last, a sign that the crisis in the world economy as a whole was worsening.

Mexico, along with Brazil (debts of $80 billion) and Argentina (debts of $38 billion) which soon followed in demanding that their debts be rescheduled, was quite another matter. As the figures began to be totted up it was found not only that their debts were much larger than anyone had suspected, but that between them a failure to pay up would wipe out more than 100% of the capital and reserves of the nine largest banks in the USA. [3] Worse than that, these were countries potentially at least as unstable as Poland. Mexico’s ruling party had been in power for over fifty years and its hold looked unshakable – but unemployment was soaring, the working-class was stirring and this was a country right on the borders of the richest, most powerful capitalist state of them all. In Brazil and Argentina things were even worse – tired military regimes losing their grip in the face of economic debacle, or military defeat, and confronting militant rebellious industrial working-classes which showed no signs at all of being prepared to pay the cost of their rulers’ extravagance.

The figures for total third world debt were staggering – a colossal $610 billion worth, more than the total gross national product of Britain. Debts in Eastern Europe amounted to around another $80 billion. [4] Not all of that was owed to the private banks. Much of it was owed to other governments which had provided vast and expanding credits and subsidies to their own exporters to the debtor countries as the world slump deepened in the 1970s. Much especially by the poorer countries of the third world, India, Bangladesh, or much of Africa, which had never been much favoured by the banks, was owed to international, (government funded), agencies like the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund. But the banks it was estimated had put up some 60% of the money, and probably around three quarters of the cash which had gone to Mexico and Brazil.

One estimate, by a collection of international bankers and ‘experts’ called the Group of 30, was that as much as $200 billion of the money lent by the banks would be difficult to collect – was bad debt. On top of that the raging economic crisis in the major industrial countries had pushed thousands of companies into bankruptcy, and a number of major multinationals (Dome Petroleum with debts of $4 billion, or International Harvester with debts of $4.2 billion) were in serious trouble. [5] Both the degree of integration and the vulnerability of the financial system were attested to when a small bank in Oklahoma, USA, Penn Square, went bust in July, and the much larger Continental Illinois found itself with losses of $220 million on money it had lent on via Penn Square. [6] As if to symbolise the whole situation, the head of the bankrupt Banco Ambrosiano in Italy was found hanging under Blackfriars Bridge on June 18 in mysterious circumstances. 1982 was not a good year for bankers.

Not surprisingly, the prophets of armageddon had a field day. Many Marxists who perhaps should have known better got carried away predicting the imminent collapse of the world banking system, but it was understandable given that Denis Healey was doing the same thing. The IMF meeting in September 1982 was, he argued, ‘the last chance to save the world from a catastrophe even greater than the slump of the 1930’s’. He went on ‘Many countries in the third world face the prospect of economic collapse, political anarchy and mass starvation. The risk of a major default triggering a chain reaction is growing every day.’ [7]

Denis Healey was wrong about the impending collapse of the international banking system. He was much more on target when he talked about the prospects for the third world. The rescue operations which were launched with astonishing speed in the months after the Mexican crisis in August showed the IMF and the world’s major states still had the capacity to contain the crisis, and in particular to prevent the collapse of any major bank. But their actions, it will be argued in the course of this article, have not solved the crisis, and may only have postponed the day of reckoning to a later date.

Two developments are necessary if the debt crisis is to be resolved. Neither is very likely. One is a sustained recovery in the world economy. But the debt crisis itself is prolonging tne current slump, reducing the level of world trade, and will limit the scope of any recovery. This makes it impossible for the debtor economies to sell enough goods on world markets to enable them to cover their repayments. The other condition is that the working-class of the debtor economies is prepared to accept the reductions in its standard of living, the increase in exploitation, necessary to free the resources, the surplus-value, demanded by the banks.

In reality the debt crisis is undermining the stability of the regimes whose very authoritarianism was so attractive to the bankers in the 1970s when they were making the loans. The strikes in Brazil, and Venezuela, the demonstrations in Chile and Argentina, are the events that have really frightened the bankers in recent months. For revolutionaries this is the real significance of the debt crisis – although these events will not be examined in any detail here.

This article is devoted to explaining the real roots of the debt crisis, and an examination of the response to that crisis both in the West, and in the major debtor economies of Latin America in particular. Most analyses of the debt crisis have been superficial because they separate out that crisis from the deep-rooted crisis of the system as a whole. That is why this article begins by looking briefly at Marx’s analysis of banks and banking crises.

Financial crises have a long history. Charles Kindelberger in his book, Manias, Panics and Crashes, traces them back to the South Sea Bubble of 1720. [8] He along with many others sees them as having a logic of their own. Thus he describes a repeated saga of speculative manias, waves of irrational ‘get rich quick’ optimism, followed by the inevitable crisis, panic and crash. It is a rich tale, of swindlers and fall-guys, foolish bankers and financial mismanagement by the state. It is also a misleading tale.

There have been examples of purely monetary crises, or of purely speculative bubbles, with little or no connection with the state of the productive base in the economy. But they are the exception, not the rule. The most serious crises since the emergence of industrial capitalism have always involved severe slumps, with chronic overproduction and mass unemployment in the productive heart of the system. On several occasions, as in 1847 which Marx studied closely, the collapse in 1890 of the London firm of Baring (which had over-lent to traders in Argentina), and the 1929 Wall Street Crash, the financial crisis has marked the turning-point from boom to slump.

Not surprisingly economists have often seen the root of the crisis in the operations of the financial system itself. Some suggest that if only bankers had not been so foolish or if the government had not mismanaged things the slump could have been avoided. Others advocate reforms of the system, government regulation, even nationalisation, of the banks, as the solution. Marx was scathing about such ideas and the theories that underpinned them:

The superficiality of political economy shows itself in the fact that it views the expansion and contraction of credit as the cause of the periodic alternations in the industrial cycle, whereas it is a mere symptom of them. [9]

Banks make their profit by lending out money. More accurately they make money out of the difference between the interest they charge on loans and the interest they have to pay to attract deposits. One reason why British banks have long been so exceptionally profitable is that they have not until recently paid interest at all on most of the deposits they receive – banks elsewhere have not been so fortunate. It is still the case today that the bulk of bank lending is to governments or, even more important, industrial companies, rather than to individuals. The interest they receive on those loans represents in either event a share of the surplus value produced by workers.

For the capitalists, however, money has the capacity simply to breed more money. The holder of a sum of money only has to place it in a bank, or buy shares, or a unit trust to receive a regular, apparently guaranteed, return. ‘It becomes as completely the property of money to create value, to yield interest, as it is the property of a pear tree to bear pears.’ [10]

Interest only represents a share of the total surplus value produced by workers, which is acquired by a particular section of the capitalist class, the bankers, and those who simply lend money without engaging in production. Yet why is it that those who control industrial capital are willing to tolerate such a group of parasites receiving a share of their profits?

The answer lies in the fact that there are advantages for capitalists from having institutions which specialise solely in the handling of money. Banks act to concentrate sums of money in large quantities and make them available to capitals when they need them. In particular, as capitalism develops so does the scale of investment. Capitals cannot simply invest their profits as they flow in, but have to wait until they have sufficient funds to build a new factory or purchase a new set of machines. At any one time some capitalists will be building up hoards of idle cash, whilst others will be seeking to invest. Those with spare cash can benefit by placing it in a bank. Those who want to invest can borrow even larger sums than those generated by the profits of their own business.

Banks do not simply lend out funds from one group of capitalists to another. They also act to speed up the whole process of the circulation of money in an economy, by minimising the idle reserves of cash which capitalists have to keep. Indeed, although this is not the place to discuss it in any detail, banks, by lending out money, by the creation of credit, can effectively increase the amount of money available within an economy. Banks enable the system to economise on its use of what Marx called ‘money proper’ – gold or state-issued paper money – through the generation of what he called ‘credit money’.

In the early days of banking this occurred when banks issued ‘bank-notes’ or promises to pay, as substitutes for the gold they held in their vaults. But this was a system vulnerable to abuse, and highly precarious if the banks issued too many notes. Since 1844 in England, the Bank of England has had a monopoly over the issue of banknotes, and the amount issued is controlled by the state. However, that has not stopped the generation of credit-money by the banks. In modern capitalism the vast bulk of what economists call money consists not of cash, coins or paper, but of bank deposits. Marx himself noted the emergence of this system, observing that in Scotland whereas ‘currency has never exceeded £3 million, the deposits in the banks are estimated at £27 million.’ The banks only kept cash reserves amounting to about a tenth of their deposits, relying on the fact that its customers would only withdraw all their deposits in cash if there was panic, ‘a run on the bank’. Thus, ‘It is possible therefore, that nine-tenths of all the deposits in the United Kingdom may have no existence beyond their record in the books of the bankers who are respectively accountable for them ...’ (Capital, Vol. 3, p. 603)

The expansion of the system of credit is simultaneously an expansion of debt. As long as capitalism is expanding, prices are rising and profits are flowing in, old debt can easily be paid off, and the temptation to acquire new debt is strong. But as soon as the system begins to falter the fragility of the whole ‘superstructure’ of credit and debt is exposed. The expansion of the credit-system occurs in response to the growth of production and trade. Correspondingly, in a time of slump the credit-system rapidly contract seriously aggravating the crisis.

A slump however also exposes the inner limit of the banking-system, the reserves which banks have to hold against a withdrawal of deposits. For banking rests in a sense upon a gigantic confidence trick – the pretence that deposits which have been lent out are really still there, capable of being withdrawn at any time. As long as deposits and withdrawals roughly balance out there is no problem. Banks will tend to push their reserves down to a minimum, as they expand their profits through lending out money as quickly as it comes in. But in a slump withdrawals will rise and deposits slow, as capitals find their profits falling. An individual bank may find that withdrawals are so great that it has to start calling in its loans, and bankrupt many of the capitals which have borrowed from it. Alternatively, fear that the bank has lent out money to debtors who cannot repay may provoke a run on the bank. Depositors lose confidence in being able to get their money out, all seek to withdraw their money at the same time, and the bank’s reserves cannot, of course, meet the demand. The bank will collapse, the panic spread, depositors will lose their money, the supply of new loans will dry up, and a wave of bankruptcies will throw the system into a severe crisis. Banks, therefore, in Marx’s account are distinctly vulnerable.

At the same time they are powerful due to their ability to concentrate all the idle money-capital of the economy in their hands. That capital they distribute amongst the various spheres of production according to where it can most profitably be used. They speed up the process whereby capital is withdrawn from declining or unprofitable industries and channelled into the profitable and expanding. They can facilitate growth and centralisation of capital in the hands of a few large corporations. They also determine the fortunes of those capitals that start losing money or running up excessive debts. It is the banks that act to ‘bankrupt’ the weak, and promote the strong.

Yet some Marxists in stressing the power of the banks, or in focusing on the rise of what Lenin in 1916 was to call ‘finance capital’ (a virtual fusion of the banks and industry with the banks in command), have ignored the dependence and vulnerability of the banks outlined above. [11] It is true that banks can increase their share of the total surplus-value produced under capitalism at the expense of other sections of capital. It is also true that, when interest rates rise, money-lenders can prosper whilst the profits of industrial capital are falling. But the banks still depend upon the ability of productive capital to generate that surplus-value in the first place. The health of the banking-system depends upon the health of capitalism as a whole.

This issue demands that the whole boom-slump cycle of capitalism be looked at more deeply. But before doing that its worth considering another question.

One of the more remarkable features of Marx’s work is the way in which he anticipated some of these changes that were to take place within the credit system. [12] In discussing the 1847 crisis he argued that the Bank of England’s refusal to supply extra notes to the banking system when the banks were in trouble served only to intensify the crisis. But, he argued:

As long as the social character of labour appears as the monetary existence of the commodity and hence as a thing outside actual production, monetary crises, independent of real crises or as an intensification of them are unavoidable. It is evident on the other hand that, as long as a bank’s credit is not undermined, it can alleviate the panic in such cases by increasing its credit money, whereas it increases this panic by contracting credit. The entire history of modern industry shows that metal [i.e. gold] would be required only to settle international trade and its temporary imbalances, if production at home were organised. The suspension of cash payments by the so-called national banks [i.e. the refusal of the Bank of England or other central banks to provide gold for pound-notes] which is resorted to as the sole expedient in all extreme cases, shows that even now no metal money is needed at home. (Capital, Vol. 3, p. 649)

Two points are worth making about this passage. One is that Marx clearly distinguishes between the use of money within a national economy, where state guaranteed paper notes can indeed completely replace gold – and the use of money for international payments. A state can print as much paper-money as it likes – but there is no guarantee that this will be acceptable as a means of payment to sellers in other countries, especially if, as with the Argentinian peso recently, it is a currency liable to lose its value rather rapidly. To pay off their debts to traders or banks in other countries national groups of capital and the states which represent them, need money which is internationally acceptable – gold, or national currencies which are considered to be as ‘good as gold’ and are therefore held as reserves of foreign exchange. The pound sterling in the years up to 1931, and the dollar up to 1971, were therefore tied to gold as a guarantee of their value on the world market. Since 1971 when the Americans abandoned their commitment to exchanging their reserves of gold for dollars held abroad, gold has had no official role to play in the system. But that, as the exchange rate chaos of recent years has shown, did not settle the issue. Only a world state could issue paper money which would be automatically acceptable everywhere. As it is the world economy remains in a situation where, despite growing internationalisation, the key world reserve currency, the dollar, is issued by one particular, if powerful nation-state. [13]

To return to the passage quoted from Capital Marx is also arguing that whilst state intervention can help to alleviate a crisis (or intensify it), monetary crises will remain an inevitable result of the cyclical movement of capitalism itself.

Accumulation is the process whereby capital throws back part of the surplus-value it has extracted into the production process as new investment. It is the rate of accumulation, driven by competition for ever greater profits, which drives the system forward, generating the booms, and, when it falters, the slumps. It is accumulation which in expanding the forces of production, and increasing the productivity of labour, also exposes the limits set to capital by capital itself, by the way the system is organised. Accumulation tends to undermine itself, because it cuts into the rate of profit, the flame which lures it forward. The law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall lies at the root of Marx’s explanation of why the system should sink into deeper and more prolonged crises as it grew older.

The arguments concerning this have been extensively discussed in other issues of this journal. [14] What I want to emphasise here is that Marx’s formulation of the law is at a very high level of abstraction and by itself does not provide a sufficient explanation of how the system moves from boom to slump. Most obviously it is an analysis applied to capital in general, ignoring the unevenness which arises from the competition among different capitals. Some capitals (especially the most efficient with lower costs of production) will be able to gain at the expense of others, even in a crisis.

The unevenness of the system relates to a second point. The rise in the organic composition of capital, and thus the pressure on the rate of profit from this source, is something which occurs only gradually, over a lengthy period of time, and subject, as Marx showed, to a whole number of countervailing tendencies. Yet the system has not slid gradually into a state of stagnation as its driving spark faded away. On the contrary, the underlying tendency has expressed itself only through a cycle of booms, or periods of expansion, in which the rate of profit rises, at least at first, only to fall even more sharply in the ensuing slump. This short-term cycle, which when Marx was writing lasted almost exactly ten years from peak to peak or trough to trough, also has to be explained.

Marx argued that the length of the ten-year cycle had its roots in the lifetime of fixed capital. The recovery of the system after a crisis will also form the ‘starting-point of a large volume of new investment’. [15] Whilst this investment is being made, new machinery introduced, new factories built, demand for means of production is high, encouraging the rapid expansion of industries such as building, steel and engineering. Money is being thrown into circulation, new workers are being taken on, and the level of demand rising ahead of the increase in production which this new investment will generate. Sales are easy, prices are rising, and profits tend to rise as well, encouraging a further expansion of production.

But eventually as this new investment comes on stream, the extra factories and machinery start to function, more and more commodities are thrown onto the market, and a situation of overproduction begins to develop. With full employment and a high level of demand the wages of workers and the price of raw materials will probably have risen. Capitalists find their profits being squeezed both by rising costs and the need to cut prices in order to ensure sales as the market becomes overstocked. They start to cut back on investment, which leads to sharp fall in demand for those industries producing investment goods – building, steel, engineering etc. Those industries, having expanded to meet the extra demand at the beginning of the cycle, are now faced with chronic overcapacity, and start to lay off workers and close down plant. The whole system begins to move in a vicious spiral downwards, as the fall in investment leads to a fall in demand throughout the economy.

If the rate of profit begins to fall as the boom nears its peak, it falls much more rapidly as a result of the slump itself. The fall in investment, the contraction of the economy, the rise in unemployment, all mean that capitals have great difficulty in selling their commodities – in ‘realising’ the surplus-value that is produced. Yet the slump also generates ‘counteracting’ forces which ease the pressure on profitability. The price of raw materials, capital goods and labour may all fall sharply. Some capitals will go bankrupt leaving a larger share of the market, and assets which can be purchased cheaply, by those which remain in the arena.

A revival of the system, a return to boom, however, depends on a revival of investment, and the low level of demand itself acts to discourage any such thing. But this is where the ‘lifetime’ of fixed capital enters the picture. Those capitals which survive the slump will eventually have to replace the machinery which they acquired at the beginning of the cycle. The very act of replacement, especially when it is bunched together by a number of capitals, serves to stimulate the industries producing means of production. They take on more workers, and reopen plant that’s been mothballed, demand in the economy as a whole begins to revive, and the cycle resumes again.

Marx argued that the short ten-year cycle which characterised the nineteenth century was thus rooted in an average ten-year lifetime of machinery. But he also argued that the length of the cycle, and especially the timing of the move from boom to slump, could be affected by other factors, including the operations of the financial system.

Here again we have to develop, make more concrete, Marx’s analysis of the rate of profit. That took no account of the division of the total surplus value between the interest received by the banks, and profit in the strict sense of the return received by productive capital. Obviously, movements of the rate of interest can affect the amount of profit available to the rest of the capitalist class, independently of what happens to the rate of profit in general. Shifts in the rate of interest also go hand in hand with the cycle of capital which we have just discussed.

It is difficult to summarise the most relevant content of Marx’s work in this area. As Engels lamented, Marx left only a mass of incomplete and disorderly notes on the subject. [16] Much of this was concerned with the details of contemporary crises and debates. For example, Marx placed a great deal of emphasis on commercial credit, debts contracted between commercial and industrial capital themselves, which is much less significant today. But the general picture which Marx provides of the expansion and contraction of the credit system in the course of the cycle, which we outlined in the last section, remains extremely relevant. Moreover Marx himself provides a concise account of the way in which the rate of interest changes:

If we consider the turnover cycles in which modern industry moves – inactivity, growing animation, prosperity, overproduction, crash, stagnation, inactivity, etc. ... we find that a low level of interest generally corresponds to periods of prosperity or especially high profit, a rise in interest comes between prosperity and collapse, while maximum interest up to extreme usury corresponds to a period of crisis ... yet low interest can also accompanied by stagnation, and a moderate rise in interest by growing animation. The rate of interest reaches its highest level during crises, when people have to borrow in order to pay, no matter what the cost. (Capital, Vol. 3, pp. 482–3)

The rate of interest is governed by the supply and demand for what Marx called loanable capital’. In the aftermath of a crisis, the period of stagnation and inactivity, interest rates will fall and remain low, because capitals with money to spare will be willing to lend it out again, or redeposit it in the banks, but the demand for loans for productive investment will be weak. As the system begins to expand again, and investment rise, the demand for loans will increase but so will the supply. Sales will be easy, prices rising, and profits high. In this period of prosperity, the credit system expands and more money flows into circulation, in response, as we saw earlier, to the expansion of the productive system itself: ‘The ease and regularity of returns, combined with an expanded commercial credit, ensures the supply of loan capital despite the increased demand and prevents the interest rate from rising.’ (Capital, Vol. 3, p. 619)

However, the expansion of credit, and the relatively low level of interest in relation to the rate of profit, themselves encourage an acceleration of investment and borrowing. The rise in prices, fuelled by the growth of credit, encourages speculation on a further rise in prices. Capitals borrow both to expand production even further, and, increasingly, simply to gamble on purchasing commodities, shares or property, hoping to make a quick profit from a rise in prices which will also enable them to pay off their debts.

The system then comes under pressure from two sources. On the one hand, profits actually generated by productive capital fail to rise to match the vast expectations generated by the speculation, and may even begin to fall, as costs rise and markets become glutted. On the other hand the rapid expansion of lending stretches the reserves of the banks to the limit. Interest rates rise rapidly as the demand for funds far exceeds the supply provided by the return of money as deposits to the banking system. But this rise in interest rates in turn cuts into the rate of profit of those capitals that have borrowed heavily.

The spiralling of credit and speculation means that the crash may come abruptly.

... the appearance of very solid business with brisk returns can merrily persists even when returns in actual fact have long since been made only at the cost of swindled money-lenders and swindled producers. This is why business always seems almost exaggeratedly healthy immediately before a collapse. (Capital, Vol. 3, pp. 615–6)

The banking system does not determine the course of the cycle, but it does accelerate and extend the booms, only to make the entire system dependent upon debt, vulnerable to a rise in interest rates and liable to crash. As the crisis begins, the interest level soars to ‘usurious rates’. Capitals faced with falling demand and prices cannot pay off their debts and are desperate to borrow more. The capitals with money in the bank withdraw it to keep themselves afloat. The rise in the rate of interest benefits the money-lenders, and forces large numbers of companies into bankruptcy.

But if the crisis becomes serious it may spread to the banks themselves. In that event there is a rush to turn bank deposits into cash, banks have to close, borrowing becomes impossible, and the whole system of credit and debt collapses. The crisis in the financial system in turn feeds back into the industrial crisis, aggravating it, and prolonging the stagnation which follows. As Marx summarised the whole process:

If the credit system appears as the principal lever of oveproduction and excessive speculation in commerce, this is simply because the reproduction process which is elastic by nature is now forced to its most extreme limit ... The credit system hence accelerates the material development of the productive forces and the creation of the world market, which it is the historical task of the capitalist mode of production to bring to a certain level of development, as material foundations for the new form of production. At the same time credit accelerates the violent outbreaks of this contradiction, crises, and with these the elements of dissolution of the old mode of production.

We have, therefore, three elements to Marx’s account of crises.

There is his explanation of the basic tendency of the rate of profit to fall, the rise in the ratio of dead to living labour, or of the amount of capital invested in means of production relative to the source of surplus-value. This means that over time, as the system ages, it should become prone to deeper and more prolonged slumps, whilst the booms become shorter and weaker. We have his account of the boom-slump cycle itself, which explains why even in a lengthy period of crisis and stagnation, the system continues to rise and fall, with periods of acute slump followed by limited recoveries. Finally we have his explanation of how the system of credit and banking is drawn into the cycle, in turn influencing the movement of production – helping to sustain and accelerate the booms, only to intensify the slumps which follow.

The relevance of all three of these strands to understanding the world crisis of the 1970s and 1980s should become apparent in the account which follows. But this is by no means obvious, not least when it concerns Marx’s analysis of the banking system and the course of the cycle. The capitalism which Marx examined was far less developed, much less international, much less concentrated in large corporations, and above all less subject to the growth and activity of nation states than it is today.

One consequence of those changes is a shift in the character of the boom-slump cycle. In the nineteenth century, the slump and the contraction of the system of credit went hand in hand with a wave of bankruptcies, a fall in prices (compensating for their rise in the boom), and a wiping-out of debt as it was either paid off, or the debtors were bankrupted and their assets sold. But nineteenth century capitalism consisted of a large number of small firms. The banking system itself was much less integrated and centralised than it was to become by the beginning of the twentieth century. A wave of bankruptcies, even the collapse of a bank or two, did not halt, indeed only briefly interrupted, the upward rise of capitalism. Indeed crises, in rationalising the system helped to restore the rate of profit of those capitals which survived.

Crises therefore were the mechanism by which capitalism resolved its own internal contradictions, ‘violent eruptions which for a time restore the disturbed equilibrium’ as Marx put it. They also served to accelerate the centralisation of capital in the hands of a much smaller group of large capitals – a process facilitated by the banks themselves, with their ability to concentrate large sums of money-capital. Hilferding, observing this growth of vast monopolies interconnected with the banks, suggested in his classic work Finance Capital that the crisis could be at least alleviated, and perhaps even resolved altogether, by this new type of ‘organised capital’.

But the crisis of the 1930s was to show that the concentration of capital in the hands of a few large corporations only intensified the difficulties of the system, once it entered into slump. A crisis now meant the bankruptcy not of a number of small firms but of several large corporations with a devastating impact on the whole national economy. A collapse of one bank now threatened an entire integrated banking system. Not least the internationalisation of the system meant that the crisis was transmitted from one country to another at rapid speed.

However, the crisis of the 1930s would also thrust upon the states, for the first time apart from war, the task of managing their national economies. The 1930s marked the advent of an era in which the concentration of capital was matched by the intervention of the state – increasing spending on arms and welfare, nationalising key sectors of the economy, propping up weaker capitals and bailing out banks in trouble and proclaiming its ability to prevent slumps and sustain growth for ever.

The crisis of the 1970s would, however, expose the myth of the Keynesian managed economy. Yet the protracted, stagflationary crisis of the last decade has been different from both the short sharp shocks of the nineteenth century, and the chronic depression of the 1930s. The persistence of inflation through both boom and slump has been the most obvious difference, but the new phenomenon of ‘stagflation’ (stagnation and inflation combined) is but a symptom of the much deeper transformation in the character of the system. At root it is a product both of the enormous concentration of capital, the resistance to price-cutting of the few giant corporations which dominated most industries – and the intervention of the state to prop up the system as the crisis deepened. That intervention involved, not least, supporting the vast and international system of credit and debt which had grown at accelerating pace in the post-war era. The major states and their central banks have had some success. There has, so far, been no major banking collapse, no sharp contraction of the credit system of the sort we discussed earlier.

But these features of the crisis also mean that the system is trapped in stagnation – there has been no thorough clearing-out, no rationalisation of the system through bankrupting the weak. the inefficient, and all those who cannot pay their debts. Instead the contradictions persist, the system staggers from slump to weak recovery, back into slump – and the debts have just grown and grown – until some of the suppressed tensions finally burst out in the course of 1982. It is this story – of banks and the states, debt and stagflation, and why it is the international banking system, the lending to countries like Poland and Mexico, which has finally broken down – that will be told in the rest of this article.

The history of international banking is a long one. As far back as the sixteenth century the banking houses of the Medicis and Fuggers were making and losing fortunes out financing the wars of the Holy Roman Emperors or the Kings of Spain and France. The Rothschilds, based in Frankfurt, London and Paris, had become the first ‘multinational’ banking firm in the early 1800s. [17] Marx, however, whilst noting the international repercussions of banking crises does not discuss them in any detail. This was partly a matter of levels of abstraction – Marx never wrote the volume on the world market where such developments would have been discussed. It was also because the significant period of capital export from the heartlands of developed capitalism in Western Europe to the rest of the world only began in the 1880s as he was dying.

The bulk of bank loans and other overseas investment in the 19th century came from Britain and went to finance railways and governments in the rest of Europe and America. But as rates of profit declined and the system entered into stagnation in the 1880s the search for profitable investment opportunities led those with spare capital further afield, and the competition became more intense. The rise of the new industrial powers of the United States and Germany threatened the dominance of France and Britain. The export of capital became intertwined with imperialist rivalries and the scramble to partition the globe between the major powers. It was this development which Lenin summed up by establishing the connection between the growth of ‘finance capital’, the concentration of capital in the hands of large monopolies intertwined with the banks, the export of capital and the epoch of Imperialism.

Although that thesis can be criticised in detail it did capture some of the decisive tendencies of the capitalism of that era. [18] Bank lending to foreign governments in particular was highly profitable but very risky. The American state of Mississippi is still listed in London as a bad debtor from its default in the 1850s. The prestigious London house of Barings, as we noted, collapsed in 1890 after guaranteeing dodgy loans to Argentina. Elsewhere however the accumulation of debt by sovereign borrowers was the cause or the excuse for intervention by the imperialist powers – in Egypt where the British took control in the 1880s, in Turkey where a consortium of German, British and French became the manager of the finances of the crumbling Ottoman empire, and in the Dominican Republic in the Caribbean where in 1907 in exchange for a loan, an American appointee was put in charge of the customs revenues, and troops were dispatched in 1911 and 1916 to guarantee that the money was collected. [19] After the Russian revolution in 1917, however, French holders of Tsarist bonds lost the lot, proving that international lending remained qualitatively different from lending to companies whose assets could always be flogged off after they had been taken to the bankruptcy court.

Capital export, and the markets and higher profits that it generated helped to sustain the rapid expansion of the system in the early years of the twentieth century. Capital export, including both bank lending and loans by individual ‘bond-purchasers’ tended to increase in times of slump in Britain, acting in counter-cyclical fashion to offset the severity of the crisis within the domestic economy. In the 1920s however, the rapid growth of international lending from the United States in particular served both to accelerate the boom and deepen the subsequent crash.

The events of 1929–32 vividly confirmed Marx’s account of the character of banking crises. In the United States nearly half the banks collapsed. In 1931 the Rothschild-controlled Kreditanstalt, Austria’s largest bank closed provoking a chain reaction of deposit withdrawals and bank failures throughout Europe. Germany, which had received large inflows of short-term money in the 1920s, was faced with a demand that the money be repaid instantly and was forced to default on its debts. In both Germany and the United States the collapse of the banking systems added to the severity of the crisis and as new loans dried up thousands of companies had to close. In both countries unemployment was as much as a third of the working population in the depths of the slump. In Latin America the fall in the price of raw materials meant that Bolivia defaulted in 1930, to be followed by names familiar in the current crisis – Peru, Chile, Brazil, Mexico. [20]

International defaults were in some ways less serious for the banks in the 1930s than the crises in the domestic economy. Instead of lending their own money, banks had in most cases simply sold bonds to wealthy individuals on behalf of the government which issued them. Nevertheless in the wake of the crisis the flow of capital from the world’s main financial centres dried up. The issue of foreign securities by United States financial institutions declined from an annual average of $1151 million in 1924–28 to $229 million in 1931 and nothing at all in 1934. [21]

Crudely summarised it can be said that the 1930s marked an end to the era of finance capital and the beginning the era of state capital not just in Russia but throughout the capitalist world. In the aftermath of the crisis states moved to prop up their domestic States. The Roosevelt government stepped in to provide insurance for depositors and extend the powers of the Federal Reserve central bank over the banking system. In Germany the banks were first nationalised by the Nazis and then allowed to operate only under the strict direction of the state. In France four of the largest banks and thirty-four insurance companies were nationalised at the end of the Second World War. [22] In Britain in the 1930s and 1940s both Tory and Labour governments pursued ‘cheap money’ policies, keeping the basic interest rate (the Bank Rate) as low as 2%, to encourage industrial investment.

The postwar order established in the West under American hegemony put an end to the period of national isolation and autarchic policies which had marked the 1930s and led to the second world war. The interests of American capital demanded that the markets of Western Europe be opened up in the name of free trade. But individual states retained the controls they had established over their domestic banks, and the network of exchange controls which limited the mobility of private capital. International bank lending to cover balance of payments deficits was to be in the hands of government-funded international agencies which were dominated by the United States. Capital export in the 1950s and 1960s consisted mainly of either government loans and aid, or direct investment by American and other multinationals, mainly in other industrial countries.

In the 1950s as the long boom gathered momentum the banks in America and Europe were still both tightly regulated and rather minor actors on the international scene. This situation would change for two main reasons.

One was that as the boom accelerated so the demand for bank loans increased as in the booms discussed by Marx. This occurred slowly. Most large corporations were making ample profits to finance their investments internally. But in the 1960s the competitive pressures began to increase, the scale of investment grew, and loans were cheap and readily available. Creeping inflation was rooted in the concentration of capital and the implicit agreement among the giant monopolies to raise prices in line with each other and never to engage in price competition. But inflation also both encouraged and was fuelled by the expansion of credit. Inflation encouraged companies to go into debt because it lowered the value of past debt in real terms, whilst at the same time raising the cost of new investment. The speeding up of the circulation of money by bank lending (which was increasingly efficient and centralised) in turn helped to sustain the overall level of monetary demand which meant that prices could be raised in the expectation that sales would not fall as a result.

By the late 1960s bank lending was accelerating hand in hand with inflation in most of the major western economies. Levels of debt owed by governments, companies and individuals were rising correspondingly. In the past this would have placed increasing pressure on the monetary reserves of the banking system, forcing up interest rates and cutting off the boom. This did not happen only because governments intervened to increase the money supply, in effect printing more money and expanding the reserves of the banks thereby providing as one Marxist has termed it a ‘pseudo-validation’ of the increase in the prices of commodities and sustaining the whole inflationary process. [23] States were finding that they had made a ‘one-sided bargain’, whereby they were committed to propping up the banking system as a whole but had lost all control of the process of bank lending. [24]

The second development that undermined state regulation of the banks was the re-emergence of international lending but in a form quite different from that of the 1920s. The postwar expansion of the system saw an even more rapid growth in the level of world trade, the size and number of multinational companies, and the mutual interdependence of national economies. The revival of international banking was a response to these developments. American banks set up branches overseas to service American multinationals. British banks in London began to receive deposits in dollars which they could then profitably lend out again. American moves in the 1960s to control interest rates and the flow of funds abroad only served to encourage American banks to transfer their base for lending to American and other multinationals to Europe, and especially to London where Harold Wilson’s 1964 Labour government allowed them great scope to operate. [25]

The emergence of the Eurodollar market, as it came to be known, marked a new phase in the international integration of the system. The Euromarkets (which came to include lending in other Euro currencies – sterling, marks and yen as well) were truly international markets in that they involved the borrowing and lending of currencies outside of their country of origin. Lending through the Euromarkets was more profitable because banks were not subject there to government controls, which usually demanded, for example, that they keep a fixed proportion of their deposits as reserves. In the Euromarkets reserves were minimised as banks maximised their lending. The use, via the markets, of offshore tax-havens such as the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg and Panama also enabled banks to escape taxation. On one estimate the average worldwide effective tax rate for American banks on their profits was only 19% in the 1970s. [26]

The growth of the Euromarkets was fuelled by the American balance of payments deficit which widened in the 1960s with the costs of the Vietnam war and increased overseas investment. As dollars piled up in the hands of holders outside the United States, they were redeposited in the Euromarkets for further lending. Even central banks in Europe began to deposit their foreign exchange reserves with banks in London, undermining their own attempts to keep the markets under control. Between 1965 and 1973 the size of the market (excluding interbank transactions or deposits by one bank with another) grew from $15 billion to $132 billion. The internationalisation of the money markets began to undermine the ability of individual states to manage their own national currencies, and provided ample opportunity for speculative movements from one currency to another. This in turn helped to undermine the whole postwar order of stable exchange rates which finally collapsed in 1973.

In the period leading up to the return of the world system to slump in 1974 however, the role of domestic lending was still more significant. Some observers have argued that the length and scale of the long postwar boom is attributable to the inflationary generation of credit, that the ‘western economy sailed to prosperity on a sea of debt’. [27] This is extremely dubious. The expansion of credit did not take off until the late 1960s, after 20 years of boom, and was far too unstable to do more than extend the Boom for a few years; What is true is that in the early seventies the pressure on profit margins on the one hand, and attempts by governments to follow Keynesian reflationary policies as the boom faltered on the other, meant an inflationary explosion of both private company and public debt. The rate of growth of bank loans in the United States accelerated from 9.0% a year between 1965 and 1969 to 15.2% a year in 1970–73. [28] The boom was also becoming more speculative. Inflation now meant that higher and quicker profits could be made from speculating on property development or the stock exchange, or commodities such as wheat and copper, than from productive investment in factories and machinery.

The 1974 slump, precipitated by the oil price rise, but with far deeper roots in the declining profitability of industrial capital, put an end to the speculative boom of the early 1970s. In Britain the collapse of the property market threatened the network of secondary banks which had sprouted in the previous decade. The financial crisis had all the hallmarks of those analysed by Marx with one important difference. To prevent a panic and the crisis spreading to the banking system as a whole the central banks intervened. In Britain the Bank of England put up $2 billion in a lifeboat operation to rescue 26 financial institutions. [29]

But whilst the states (which intervened to bail out or nationalise the most important debt-ridden companies such as British Leyland, Lockheed and Chrysler) and the central banks (which pumped money into the banking system and held down interest rates) could prevent a collapse – they could not restore the system to health. The recovery which followed in the late 1970s was weak and fragile. Investment levels remained low, and despite low interest rates (negative for a while in real terms after inflation was taken into account) borrowing was slow to recover. This was one reason why the banks turned to new, more eager, borrowers in the third world.

The Euromarkets were also hit by the 1974 crisis. The Herstatt bank of Cologne and the Franklin bank of New York had to close after huge losses from foreign exchange speculation. For a brief period this led to a rapid shrinking of the international banking system. The number of banks involved fell almost overnight from over 200 to under 40, as deposits in the interbank market were withdrawn from any bank which lacked the most impeccable credentials. [30] The crisis exposed the degree of integration of the international financial system, created by the way in which banks deposit funds and borrow from each other – so that a failure by one bank ripples through into losses throughout the system. But the crisis also forced the central banks to announce in the Basle Concordat of 1975 that they would take responsibility for guaranteeing deposits with their respective national banks. Confidence was restored, but for the states it was a matter of responsibility without control. When international lending began to grow rapidly again they had no means of regulating it. The banks were landed between 1974 and 1976 alone with an estimated $46 billion worth of deposits from the OPEC countries such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the Gulf States (although the contribution of OPEC deposits to the growth of the Euromarkets has been exaggerated and on one estimate has been only 10% of the total). The slump meant that profitable opportunities for lending in the main industrial countries were limited. Flush with cash, on which they were having to put out interest, the banks were desperate to lend. Third world borrowers, facing large deficits on their balance of payments and often with ambitious industrialisation programmes were anxious to borrow. Between 1976 and 1981 lending to such borrowers, mainly through the Euromarkets, rose at an average yearly rate of 23%. [31]

The whole process of channelling funds from surplus to deficit countries is now often referred to as the great recycling folly. [32] At the time it was acclaimed as a great achievement by all but the most far-sighted, as a means by which the banks could continue to lend to those who wanted to spend, and thus maintain the overall level of demand in the world economy. Certainly the advocates of financial rigour, who now criticise the imprudence of the banks, fail to consider that the stagnation of the system would have been even deeper in the late 1970s if the lending to countries in Latin America and Eastern Europe had not occurred. But the suggestion that this was an act of folly on the part of reckless bankers also needs to be rejected.

Anthony Sampson in his book The Money Lenders tells of how bankers at the annual meetings of the IMF in the late 1970s would literally pursue the finance ministers of countries like Brazil and Argentina in the hope of signing deals for new loans ahead of their competitors. [33] His account of the optimism of some bankers over the mineral resources of Zaire or the stability of the dictatorship of the Shah of Iran makes them look naive and blundering rather than calculating financial sharks. It is a good story, and provides a useful corrective for those inclined to overestimate the sagacity of the ruling class or the expertise of economists. The problem with it is that it ignores just how profitable that lending proved to be. Banking is a very competitive business and as more banks, including the Japanese and tiny banks from the Midwest of the United States, entered the market, margins of profit on loans to the biggest borrowers were forced down. In 1979 Argentina was being charged an interest rate only slightly higher than that for the British electricity board.

|

TABLE I |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

8 Largest US Banks |

Total |

Foreign |

For. Rev. |

Total |

|

Citicorp |

14.2 |

9.1 |

64.1 |

68.0 |

|

Bank of America |

12.1 |

6.3 |

52.5 |

44.3 |

|

Chase Manhattan |

8.0 |

5.1 |

63.5 |

40.1 |

|

J.P. Morgan |

5.2 |

3.2 |

62.0 |

27.3 |

|

Mfrs Hanover |

5.2 |

2.8 |

54.5 |

28.2 |

|

Chemical New York |

4.3 |

2.1 |

49.4 |

17.5 |

|

Bankers Trust |

3.7 |

2.0 |

55.3 |

16.4 |

|

First Interstate |

2.3 |

1.3 |

57.2 |

7.2 |

|

TOTALS |

$55.0 |

$31.9 |

(av. 58.0%) |

$249.0 |

|

[Source: see note 34] |

||||

Nevertheless, by 1977 most of the major United States banks were making over 50% of their profits on overseas lending (in the case of Chase Manhattan and Citicorp over 70%). [34] Much of the debt was at floating interest rates, which rose after 1979 in line with the rise in interest rates in the United States and the Euromarkets. The scale of the profits American banks were making in 1980 is indicated by the table. If the banks ignored warnings about the rapid accumulation of debt, and the danger of defaults, it was partly because of the profits they were making, which could be made nowhere else, and partly also because the largest banks at least were relying on the IMF and US government to bail them out if they got into trouble. As an official of the Chase Manhattan bank told the magazine Euromoney in 1976:

On the one hand a purely technical analysis of the current financial conditions would suggest that defaults are inevitable; yet on the other hand, many experts feel that this is not likely to happen. The World Bank, the IMF, and the governments of major industrialised nations, they argue, would step in rather than watch any default seriously disrupt the entire Euromarket apparatus with possible secondary damage to their own banking systems which in many cases are already straining under their own credit problems. [35]

The lending was also highly selective. Countries which ran into trouble with their repayments such as Zaire and Peru were promptly cut off from all further loans. In the ten years after 1971 three quarters of all Eurocurrency lending to the third world went to just six countries – Brazil, Mexico, Argentina, South Korea, Peru and the Philippines. Mexico and Brazil alone accounted for a quarter of the debt from all sources. [36]

It has been argued that much of this selectivity was political, that bank loans were directed particularly to client regimes of the United States, or those particularly favourable to the operations of private, multinational capital. The manner in in which bank lending to Chile after 1973, and to Argentina after 1976 increased in the wake of American sponsored military coups is commonly used to support this claim. [37] But the argument misses the point that the real significance of these coups was that they led to a crushing of the working-class movement, and an enormous increase in the rate of exploitation. It ignores the rapid growth of lending to Eastern Europe, even though American banks played only a small role in this. But in Peru in the early 1970s US banks were willing to lend to the nationalist military regime of Velasco even whilst it was cut off from money from American sponsored international agencies after nationalising a number of American owned mining interests. [38]

What mattered to the banks were two features which characterised almost all the major borrowers. One was that they possessed either substantial mineral resources capable at least in theory of generating export revenues on the world market, or that they had already acquired a social and industrial infrastructure which made further rapid industrial development possible (some such as Mexico and Brazil had both). The other was that they were strong repressive states, capable of maintaining high levels of exploitation. As one banker revealed about one of the important state capitalist borrowers in the mid-1970s:

We like Algeria because it’s totalitarian and if the government says people will have to cut back consumption, they will. [39]

Similar considerations applied to Poland, Brazil, South Korea, and Chile after 1973.

By and large the banks preferred lending to states rather than private companies. States after all could at least in theory mobilise the resources of a whole country to pay them back. In Mexico 86% of all funds went to the government or state-owned enterprises. In Brazil the banks financed the military regime’s programme of massive state investment. A remarkable alliance was formed between the Brazilian state which accounted for 51% of industrial assets, multinationals (another 11%) and the international banks (which provided the capital necessary for rapid expansion). [40]

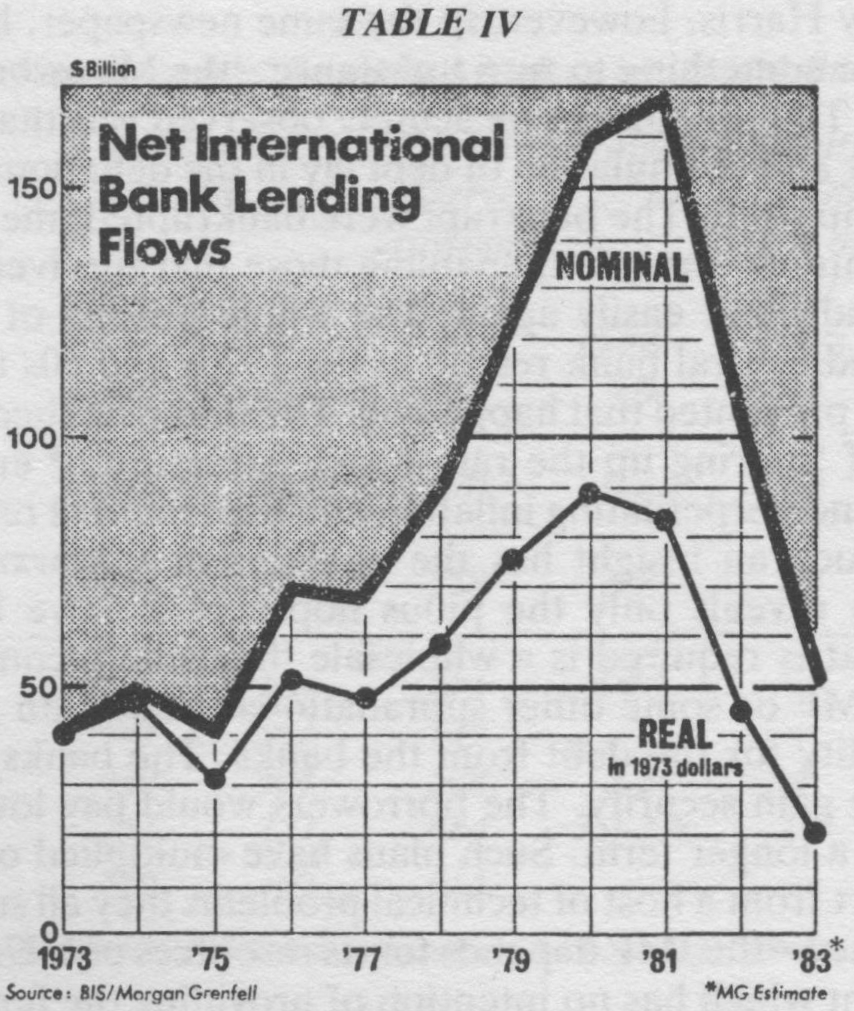

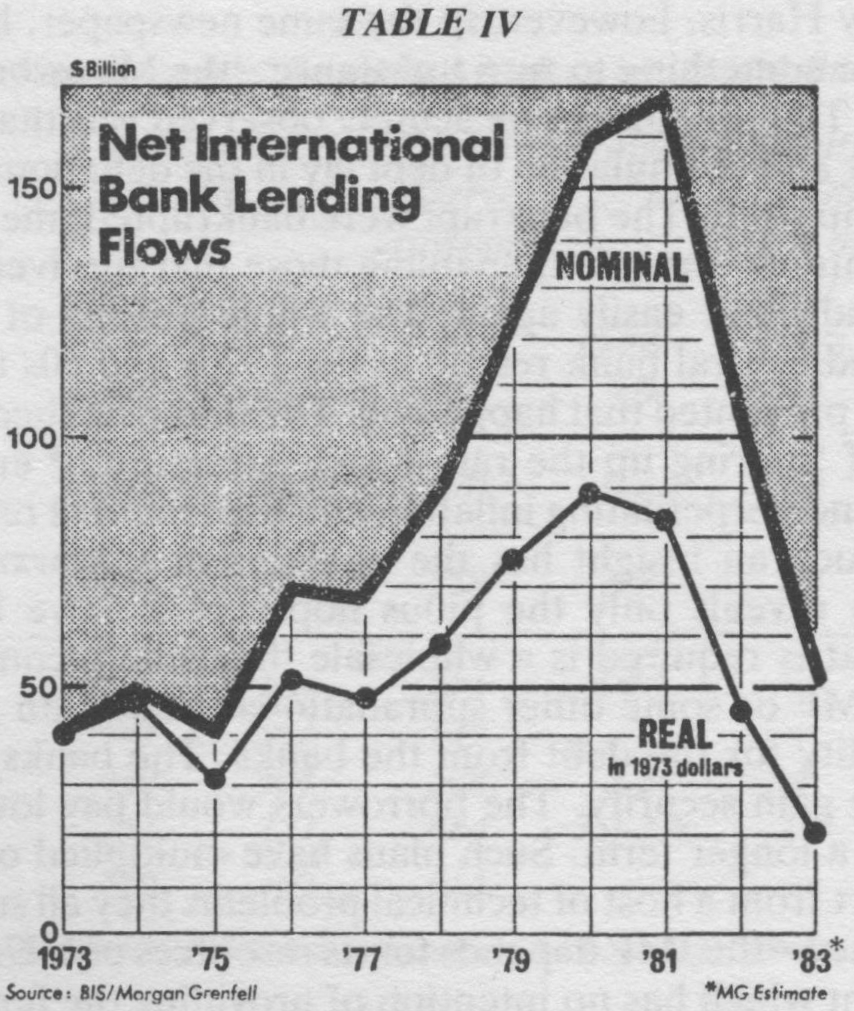

Neither vast resources and industrial capacity, nor vicious repression, could, however, guarantee that the banks would get their money back. The ability of the major debtor economies to service their debt depended also upon the health of the world economy. In the years after 1975 continuing inflation and a moderate recovery in the West lightened the burden of debt service (the proportion of exports devoted to the payment of interest plus the repayment of the sum originally borrowed, in any one year). Inflation of export prices meant that the burden of the debt diminished in real terms, but encouraged the debtors to borrow even more. The weak recovery of the late 1970s went hand in hand with a rapid growth of IT the volume of world trade especially between North and South. All that changed after 1979.

The turning point came with the appointment of Paul Volcker as Chairman of the Federal Reserve (the US central bank) in 1979. His task was to reverse the fall in the value of the dollar on world markets by restraining the growth of the US money supply. He succeeded but only at the cost of sending American interest rates soaring through the roof. With other major economies turning to tighter monetary policies as well, interest rates rose generally, threatening an already precarious financial structure inside the western economies. There is no space here to discuss adequately the repercussions of this shift for the corporate borrowers inside Western Europe and North America. Many had remained heavily indebted through the 1970s, and the failure of the 1974–75 slump to produce a clearing out of the weak and inefficient had merely postponed the problem. As interest rates rose whilst profits were squeezed the banks benefited but the burden for many companies of this debt forced them to slash their operations and throw thousands on to the dole-queue. Bankruptcies soared and a number of major multinationals found themselves in deep trouble – AEG-Telefunken in West Germany. Massey-Ferguson and International Harvesters, Dome Petroleum in Canada, several of the major steel firms and airlines in the United States. According to one observer the American banks were faced with around $100 billion on dodgy loans to corporate customers. [41]

The financial squeeze in the industrial west soon spread to the debtor economies in the third world. The integration of the world financial markets meant that the rise in American interest rates was soon reflected in the Euromarkets. At the same time the slump meant a decline in the markets for raw materials and an even sharper fall in commodity prices. In real terms, on one estimate, interest rates moved from being negative after inflation in 1979, to a positive, rate of 20% in 1981 for the major commodity exporters. [42]

The initial response to these pressures was to go on borrowing, at least by those states such as Mexico and Brazil to which the banks were still willing to lend. But the debt-service ratios were mounting rapidly (see table for figures at end of 1982). An increasing proportion of new borrowing was being used simply to pay off old debt. In 1980 the ‘non-oil developing countries’ received $45 billion from the banks but after paying interest their net receipts were only $8 billion. By 1982 their net receipts had become negative – they were paying more money back than they were receiving. [43] As the table shows the burden had become intolerable: [44]

|

TABLE II |

|||||

|

|

Total debt |

Borrowing |

Debt services in 1982 as % |

||

|

|

interest |

principal |

total |

||

|

Mexico |

80 |

56.9 |

37 |

92 |

129 |

|

Brazil |

75 |

52.7 |

45 |

77 |

122 |

|

Argentina |

37 |

24.8 |

44 |

135 |

179 |

|

South Korea |

32.5 |

19.9 |

11 |

43 |

53 |

|

Venezuela |

18.5 |

26.2 |

14 |

81 |

95 |

|

Yugoslavia |

18 |

10.7 |

14 |

32 |

46 |

|

Philippines |

15 |

10.2 |

18 |

74 |

91 |

|

Chile |

15 |

10.5 |

40 |

76 |

116 |

|

Ecuador |

6.6 |

4.5 |

30 |

92 |

122 |

|

[Source: Financial Times, 15 October 1982] |

|||||

In the latter half of the 1970s, the growth of the major borrowing countries in the third world and Eastern Europe was well above that of the industrial west, and in some cases (Mexico, Poland, South Korea) was spectacularly high. Between 1973 and 1979 the countries as a whole grew at an average annual rate of around 5%. That growth, as Nigel Harris has observed, helped to rescue the major industrial economies from the 1974–5 slump, “Providing the markets for the export of consumer and capital goods and sustaining the level of world trade. [45]

In the years 1980-83 that situation was sharply reversed. For the developing countries as a whole growth fell to 3% in 1980 and below 2% in 1982. But the aggregate figures conceal a great diversity of experience, and the severity of the crisis in particular countries. In 1982 the growth of the oil exporters plunged sharply with the fall in the oil price and the disarray of OPEC. In Latin America as a whole overall production fell by 2.4% in 1981 and 1.2% in 1982, before the debt crisis of the last year began to take its toll. In the Eastern bloc chronic stagnation set in. [46]

In some countries talk of economic collapse ceased to be the hyperbole of journalists as the figures registered falls in output not seen in any country, apart from the devastation of war, since the 1930s. In Poland output fell by an estimated 12% in 1981 and by a further 8% in 1982. In Argentina the economy dropped by 6% in 1981 and by another 5% in 1882. In Chile a highly speculative boom burst and output fell by 14% in 1982 alone. The bare statistics of course cannot convey the suffering and humiliation they involved for some, usually the poorest, sections of the population, the shortages of essential goods in Poland or the effects of soaring inflation in Argentina, or indeed the shock to the authoritarian political regimes of all three countries.

Debt, as economists say, is nothing but deferred trade. The borrowing had enabled the countries concerned to finance large current account deficits, in effect to import more than they exported. Now the situation had to be reversed, and the borrowers had to run an even larger current account surplus to cover repayment not just of the money borrowed but of the interest as well. The prospects of them doing so in 1982 or in the foreseeable future were nil.

Whilst the burden of interest payments was rising rapidly, maintaining exports was becoming more and more difficult. Commodity prices fell sharply between 1980 and 1982 by around 30% in nominal terms. [47] In real terms allowing for inflation they hit their lowest level since before the Second World War. [48] In the course of 1980 alone the price of one kilo Argentinian beef fell from 218 (American) cents to 160 cents; of Brazilian coffee from 485 cents to 317 cents; of Chilean and Peruvian copper from 260 cents to 165 cents (only cocaine of the major Latin American commodity exports kept its value). [49] The fall in the price of oil was less severe but combined with a sharp decline in the quantity of exports was sufficient to push the economies of Ecuador, Venezuela, and even non-OPEC Mexico with its special access to markets in the United States, into trouble.

In Brazil remarkable efforts were made to compensate by increasing the level of manufacturing exports, with some success. In 1981 the government deliberately engineered a sharp recession designed to cut back imports and divert resources into exports. Manufacturing exports rose by 30%, especially to markets elsewhere in the third world and oil imports were cut by a quarter. [50] For the first time in four years the economy attained a surplus on its balance of trade. The success was noted with approval by western bankers and for a time Brazil’s credit rating was well above that of other major debtors.

But the exercise was like running on a treadmill. In the first half of 1982 Brazil’s export volume actually rose by 5% whilst its revenues fell by 10% because of the fall in commodity prices. [51] Several of the major Brazilian export markets also collapsed in the course of 1982, notably Nigeria hit by the oil price squeeze, and in Latin America itself. Import controls, especially in the United States, added to their problems. Exports of vehicles and components fell by 20%. Imports of capital goods fell by 16% in 1981 and another 10% in 1982, as oil and interest payments absorbed almost the entire revenue from exports. [52] But as a result sectors of industry were beginning to grind to a halt in the absence of necessary spare parts of essential machinery, thus threatening the export drive itself.

Throughout Latin America it was the marginalised population of the shanty-towns, the unemployed (officially around 10%) and the underemployed scraping a living selling odds and ends on street corners (perhaps as much as another 30% in Brazil and Mexico), and the industrial working-class who suffered. Bankers, IMF economists and journalists would fly in first-class, stay in the local Hilton or Sheraton all expenses paid, examine the figures, talk over dinner with the local officials and make their recommendations – an end to food subsidies (an Economist magazine favourite this one, suggesting slyly that all those billions had been squandered on the poor), cuts in public spending, a general reduction in living standards.

For the bulk of the population after years of repression and savage wage-cuts there was little left to cut – no welfare state, no social security cushion. In Argentina in 1982 real wages were still 50% below their 1975 pre-coup level. In Brazil the union organisation and strikes of 1978–80 had pushed up wages in the industrial areas of Sao Paulo. But still an estimated 50% of the population had seen no benefit at all from the post-1964 ‘economic miracle’. According to the World Bank Brazil is the only country in the world where the richest 10% of the population receive more than half of the national income. (In Mexico the top 20% receive 53% of national incomes and the bottom 20% receive 3%.) Whoever benefited from the foreign borrowing it was not the working-class of Latin America. [53]

Where then did the money go? A common explanation (much in favour in right-wing circles as it diverts attention from the depth of the world crisis and the sheer burden of interest payments) is that the money was simply blown, frittered away on corruption and wasteful projects by governments, or used to subsidise a boom in luxury imports for the middle classes and spirited away across the border to buy up villas and other property in Florida and the Bahamas. If this account is inadequate it nevertheless contains an important element of truth.

The most corrupt and incompetent third world regimes in fact received relatively small sums from the banks. In the case of Zaire in the mid-1970s some of the more starry-eyed bankers seem to have been carried away by the immense mineral reserves of that country and President Mobutu’s heartfelt commitment to western interests. Perhaps some banks came under pressure, or were swayed by government propaganda, because of Zaire’s strategic significance for American plans in Africa. But by 1978 even the most patriotic banker was not prepared to go on lending to a country in which most of the $2 billion worth of loans seem to have ended up in the pockets of the Mobutu family. [54]

Zaire was a dramatic but extreme case. But the squandering of borrowed money by the local ruling-class of the debtor countries was common enough. In the oil-rich economies of Mexico and Venezuela the corruption is legendary. Between 1979 and 1982 money poured out of both countries, into tax-sheltered bank accounts in the Bahamas or property in the United States. ‘Mexicans are reckoned to hold some $30 billion in assets abroad, Venezuelans some $18 billion’ according to The Economist. [55]

In Mexico, as in Argentina, Chile and Venezuela, an overvalued currency made overseas assets relatively cheap and encouraged the flight of capital (as indeed the high value of the pound has done in Britain in recent years). In the years 1981–82 the flight accelerated. Some $8 billion is estimated to have left Mexico in the period between October 1981 and the first major devaluation of the peso in February 1982. In one week alone before the August 1982 crisis broke, and the shutters came down, an estimated $2.5 billion is said to have left the country. [56] Elements of the Mexican ruling-class at least were well aware of how serious the crisis was. In effect anything up to a quarter of the money lent to Mexico flowed straight out again, the dollars, the precious foreign exchange, used by the Mexican rich to buy up assets in the United States itself. They still hold that property. The burden of paying off the accumulated debt rests solely on the shoulders of the majority of the population living at near subsistence levels already.

In Argentina, the foreign borrowing of some $40 billion seems to have produced virtually no additional investment or sustained growth at all. In 1982 the Argentinian gross national product, despite a sharp if temporary boom in 1979, was still 2½% lower than it had been in 1974. The monetarist regime introduced after the military coup in 1975 was less thorough than in Chile but it still helped to wreck most of Argentinian industry. High interest rates and an overvalued peso were supposed to bring down inflation and rationalise the economy. Argentinian industry was faced first with a torrent of cheaper imports then with a soaring inflation rate and a collapse of the peso in 1981. Speculation was a far more profitable business than manufacturing in the years up to 1981. Companies could borrow money on the international markets and then lend it out again in Argentina at four times the rate of interest. Those who got their money out before the peso collapsed trebled the value of their original capital. Those who did not were unable to repay their overseas debts in devalued pesos and some spectacular bankruptcies of financial companies ensued. [57]

The scale of bankruptcies in the course of 1981 was such that the state had to intervene and bail out of the shareholders and take over their foreign debts. The workers thrown on the dole and those who saw their wages cut again in 1981 by over 20% had no such protection. The state was already responsible for some 40% of the economy and over half the capital investment in the country despite all the rhetoric about free enterprise. The Army controlled the steel industry jealously, and the navy the shipyards. [58] On top of that some 50% of the public debt was a result of purchases of military material. [59] In the aftermath of the Falklands war it remains the country most seriously in arrears on its debt repayments. According to former economy minister Aldo Ferrer

Argentina’s foreign debt increased by US$30 billion between 1975 and 1982. Two thirds of this represents capital flight and arms purchases. The remaining third can be traced to luxury imports, foreign tourism, and a subsidy to royalty payments and profit remission by foreign companies operating in the country – a total waste of resources from the national point of view. [60]

In Chile, by contrast, the monetarist regime following the coup 1973 was far more thorough and seemingly much more successful. But the consequences in the end were similar. Under the Allende government Chile had been effectively blacklisted in the national financial markets. The 1973 coup was the condition both for a resumption of American aid and a revival of bank lending. By 1976 wages had fallen by 50–60% from their 1972 level. Pinochet’s economic advisors, the ‘Chicago boys’ had set about a remarkable economic experiment, dismantling exchange and import controls, and uniquely for Latin American regimes dismantling the state sector. Nationalised enterprises were sold off at prices so low that the hidden subsidy to the purchasers amounted to 40–50%. [61]

In the late 1970s the Chilean economy was growing at rates of 8 or 9% a year, inflation was down from over 500% to 10% and the ‘experiment’ was proclaimed a success by economists and bankers alike. In reality the boom was hollow. Despite the rapid inflow of foreign capital, fixed investment in new factories and machinery averaged only 15.2% of GNP between 1977 and 1980, ‘one of the lowest rates in the developing world’ according to the Financial Times. [62] Chile remained dependent upon copper for half its exports and on other raw materials such as timber and fish for most of the rest. As commodity prices fell after 1980 the trading deficit soared. In 1981 several of the largest speculative enterprises collapsed. In 1982 industrial production collapsed, even the official unemployment level topped the 20% level and the state was forced to intervene.

The monetarist and free enterprise rhetoric of the Chilean government, as in Argentina, was exposed by the sheer depth of the crisis. In January 1983 the government was forced to liquidate three major banks and nationalise five others, including the two largest, to prevent their collapse undermining the economy as a whole. In May the state, under strong pressure from the international banks and the IMF, was forced to take on responsibility for repayment of much of the private sector’s foreign debt. [63]