Andrew Glyn Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Militant, No. 435, 8 December 1978.

Transcribed by Iain Dalton.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Under EMS [European Monetary System] the currencies of all the EEC countries would be linked together and could only fluctuate within very narrow ranges.

A large chunk of the foreign exchange reserves of the participating countries, probably around £17 billion, would be pooled in a fund which would be lent to countries whose currencies were under pressure. Devaluations and revaluations would be possible, but only after consultation, and presumably the agreement, of the other countries.

The German capitalists in particular are in favour of it because of the rise of the Mark against other currencies. As the Economist (15 July) reported, “Mr Schmidt is worried that his country’s currency will become increasingly vulnerable to speculation against the dollar [as international investors move their funds out of sinking dollars and into rising Marks – ed.] and will become overvalued, which will hurt German exports [by making them more expensive on world markets – ed.].”

By tying the Mark to the pound, the lira and other weaker currencies, the German capitalists hope to be able to hold their export prices down and increase their competitiveness both in European markets and the rest of the world

For the utopian prophets of a united capitalist Europe, the ultimate development of the EMS would be European monetary union with a single euro-currency issued by a European Central Bank.

While the proposals to back the EMS with substantial reserves from richer economies may give the EMS more chance of success than the ill-fated snake, however, the fundamental national antagonisms rule out the development of an integrated currency. Conflicts between competing national capitalists will scotch such a process long before it could work its way to completion.

Under the floating exchange-rate system of recent years, British capitalists have to a certain extent offset their continued low productivity growth by the downward drift of the pound. Under a monetary union this would not be possible, and the twice-as-high level of productivity in German and French manufacturing could proceed smoothly to crunch up UK industry.

The only attraction of EMS for the other capitalists is the hope that it will somehow make them competitive with their German rivals.

Roy Jenkins, in his October 1977 speech, reviving the idea of European Monetary Union, stated that wages in different countries must “remain in some kind of reasonable relationship to productivity” (Lloyds Bank Review, January 1978). The Economist reported (November 4) that Irish ministers think that “EMS membership would help them keep down wages.”

As soon as Labour Party Conference voted against the 5% pay limit, The Times commented that this provided a good reason for joining EMS. Even the CBI appears to have shifted from initial hostility to EMS to general support (Financial Times, October 24). This is probably based on the desperate hope that with the pound in the EMS, they will be able to argue more convincingly to trade unionists that “excessive” wage increases (or an “unreasonable” relationship of wages to productivity, as Jenkins would put it) would cause loss of jobs through reduced international competitiveness.

But the likely effects of the UK joining were summarised by the National Institute as doing “not much to bring down the rate of inflation in the UK; it would weaken UK competitiveness and so lead to lower exports and higher imports, lower output and higher unemployment” (Financial Times, November 6).

The irony is that German capital would be lending British capital vast sums in order that the exchange rate of sterling could be kept up so that German capital could more easily penetrate British markets. A Tory government would almost certainly join in the hope of using it to batter down on wages and justify the “stern monetary policy within the system” called for by the Economist.

|

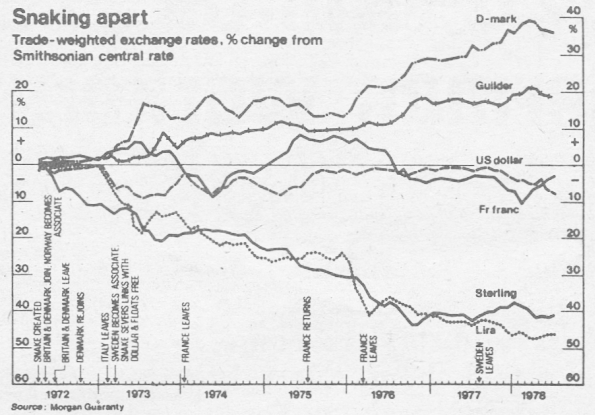

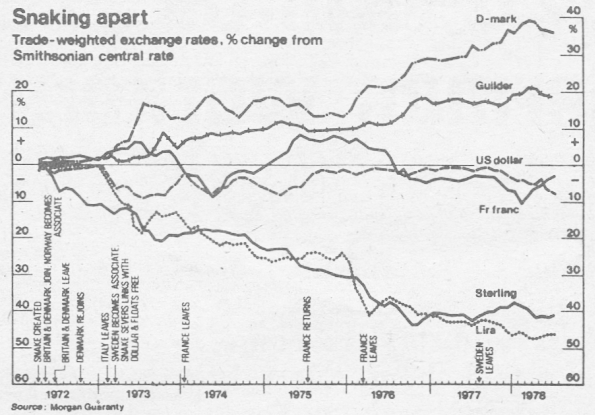

The chart shows the enormous variations in the exchange rates since the last ill-fated attempt to link the EEC currencies in the “snake”. In the last three years, the inflation rate has been 10% higher on average in Italy than in Germany – hardly a convincing basis on which to link the currencies!

It is very likely that as soon as the spectre of a left government in France or Italy is raised, or the dollar undergoes another bout of speculation, the whole edifice will collapse.

If Britain was involved, the EMS would be that much weaker, for whereas France, Germany and Italy have all achieved a similar productivity increase in manufacturing since 1973 (14% to 19%), the increase in the UK was only 3%. There is no way in the long run in which such a divergence in productive power could be contained within EMS.

While the need to plan their operations on a continent-wide scale forces the giant European companies towards breaking down the barriers between national states, at the same time the divergent national patterns of development of the productive forces and class relations make this quite impossible to achieve on a capitalist basis.

Would staying out of EMS solve anything? Obviously not, unless you think that the problems of jobs and living standards are being satisfactorily sorted out now.

In fact, there is a danger that discussion of the EMS will tend to divert attention from the capitalist crisis – world-wide and in the UK – which is the real source of these problems. Jack Straw (‘Tribune’. October 13) says of EMS that “at stake is Britain’s (our emphasis) freedom to decide its own economic policies, independent of the EEC.”

But Britain is not independent of the EEC, or more accurately, British capital is not independent of European capital inside or outside the EEC. The EMS is just one form of pressure from world capital.

The source of the pressure is the competitive nature of the capitalist system, which makes it utopian to try and opt out of it on a capitalist basis. Being outside the EMS does not preserve some ultimate “freedom” of British workers from the depredations of the capitalist class at home.

In his horror of EMS, Jack Straw seems uncritically to accept the “expansionist strategy the government is trying to follow”, as though the sovereignty of British parliament could guarantee a Labour government being able to achieve full employment if only it were not for “selfish foreigners”.

Is it true, in any case, that the Labour government is following an expansionist policy? By raising interest rates by 2½% as it did recently, the government drew praise from the City for at last applying the monetarist brakes more vigorously – the very opposite of an expansionist policy.

Behing the Tribunites’ demand for “freedom” from EEC contrains, moreover, lurks their alternative “devaluation” strategy. As opposed to the pound being supported in the EMS, the favour the deliberate devaluation of the pound on the grounds that this would boost British exports and allow for the expansion of the economy.

Past experience under the Labour government, however, shows that devaluation offers no solution for the labour movement. Big business uses devaluation, not to increase its exports, but to push up its profits, and the fall in the pound (meaning higher import prices) inevitably pushed up prices in Britain. There was no real increase in investment and no significant expansion of production as a result of devaluation.

In other words, it is clearly futile to oppose the EMS on the basis of “financial and currency freedom” for the British economy.

British big business will decide on whether or not to participate in the EMS by weighing up the likely profit and loss involved on either side, and unfortunately their attitude will be the decisive factor in the cabinet’s calculations too.

But whether British capitalism goes into the EMS or boycotts the System will not make a fundamental difference to the working class of Britain. The labour movement should not become involved in a fruitless argument as to the pros and cons of EMS from a capitalist point of view.

It is certainly necessary to analyse and explain what EMS means, and warn of what it may mean for the workers. But our real task is to answer the desperate expedients of the European capitalists with a socialist alternative which would provide a real way of bringing together the workers of Europe in the fight for the democratic, socialist planning of Europe’s productive forces.

Andrew Glyn Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 2 April 2016