Andrew Glyn Archive | ETOL Main Page

From Militant, No. 316, 6 August 1976, pp. 6–7.

Transcribed by Iain Dalton.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

In 1909 the largest manufacturing firms produced 16% of UK manufacturing output. In 1970 their share had grown to 46%, and the compiler of these statistics speculated that the figure would be two thirds by the mid-1980’s.

The fundamental factor behind this tremendous ‘centralisation’ of capital [to use Marx’s words] has been the pressure on the individual capitalists to make the maximum profits from the exploitation of their work force and to grow at least as fast as their rivals. This is essential if they are to stay in the race for technical efficiency, which is continually demanding larger and larger scales of production.

In one quarter of the industries studied by one economist,

maximum technical efficiency could only be reached by a firm actually

producing more than that required to supply the total British market

[aircraft and diesel engines were two examples]. Large size also

allows advertising costs to be spread and better terms to be squeezed

out of suppliers of components or finance: these of course simply

constitute gains for the particular capitalists in relation to other

capitalists, rather than potential advantages of society in terms of

greater productivity. To fall behind in the race for size means,

therefore, that the firm has higher costs, lower profits, less to

plough back in more advanced equipment, yet higher costs, and so on

until it is swallowed up.

Some of the giant firms are more or less monopolies in the literal sense of the word – that is they dominate the market for a particular product. Information on this is hard to come by, but the list of monopolised markets (see chart A) includes a large number of basic commodities. The more usual situation, however, is that a small number of firms produce a particular type of product. The car industry is a classic case of what bourgeois economists call “oligopolistic” competition, in which none of the small group of producers has an overwhelming advantage. To take another example, government statistics split up the electrical industry into 24 sub-sectors (TV sets, electric motors etc.) and on average the largest 5 firms in each sub-sector capture over three quarters of the sales. This does not mean, however, that there are more than 100 important firms in the industry – a giant like GEC operates in nearly every sub-sector, and in fact the largest five firms in the industry as a whole produce around two thirds of the total output of the industry.

|

CHART A In answer to a parliamentary question on April 6th, 1970 Edmund Dell stated that no comprehensive list was available of industries in which more than one half of the market was controlled by one company or group, but that it was believed to be true of a list of 156 commodities including: Man-made fibres And many chemicals [e.g. chlorine], components for cars [e.g. carburettors, electrical instruments], and types of machinery [e.g. packaging machinery]. |

A pure monopolist can set as high a price as the market will bear, but where there are a number of large firms competing, each one has to take account of its rivals reactions. When times are good, and no one firm has any particular advantage, there is tacit recognition that they all gain by charging as high a price as possible. Of course if they charge too much other firms will come into the industry and undercut them. But even where there is little price competition, the different firms will generally still fight for a bigger share of the market through advertising, product changes etc. And as soon as one of the firms gains a marked cost advantage, what was previously a stable situation will be rapidly transformed as the firm tries to exploit its technical advantage to drive out weaker rivals and capture some of their market. Such ‘disruptive’ behaviour also intensifies in slumps when it becomes a matter of survival for a firm to increase its market share in order to maintain sales and meet fixed costs.

Competition takes place increasingly on an international, rather than domestic scale. The tremendous capital accumulation in Japan and Continental Europe relative to Britain, has been reflected in the disastrous erosion of the market shares of British firms in the home and export markets. With lower costs, based on the most advanced techniques and therefore more efficient exploitation of the workers, foreign producers have been able to undercut their British rivals, forcing down prices and profits, reinforcing the vicious cycles of low investment and growth. Of course, on occasions, the stifling of competition through cartels operates on an international level as well:

“Groups of cable manufacturers in at least 20 countries have been collaborating through a Liechtenstein registered organisation, with an operational headquarters in London, to restrict their competition in world markets. Export contracts offered by customers have been secretly shared out at agreed minimum price levels.

Under the aegis of the neutrally titled International Cable Development Corporation, some British companies have recently played a leading role in strengthening the confidential arrangements for controlling competition. Tenders received from developing countries have been subject to particular market-sharing controls.

A large contract for the supply of cables to Iran is known to have gone to British interests after rival German cable makers ceded their own offer in order to avoid needless competition between ICDC members. Machinery for allocating exports was used to settle who won the business ...

... Arrangements to which they were parties include the sharing out of export tenders, collective negotiations of guidelines for price quotations, and agreed methods for undermining competitors not belonging to the ICDC.

London appears to be the nerve centre of a complex network of manufacturers who have been staging regular committee meetings in top hotels around Europe. Executives travel from as far as Japan ...

... Last year, nearly two thirds of all export business monitored by the organisation was conducted at what are known as “tolerance” price levels. A Guiding Price List has been used by member companies to deal with customers’ orders.

Some 20 national groups of companies of companies are expected to counter competition in their own home markets themselves. But they can call in the international organisation if they require help. Centrally determined procedures exist for stage-managing competitive fights to undermine competition from outsiders...” (The Times, 7/4/75)

|

The Top 15 Financial Institutions |

|

|---|---|

|

|

£ million |

|

Barclays |

14,198 |

|

National Westminster |

13,586 |

|

Midland |

9,940 |

|

Lloyds |

8,954 |

|

Halifax Building Society |

3,767 |

|

National and Commercial Banking |

3,004 |

|

Abbey National |

3,006 |

|

Nationwide |

1,547 |

|

Bank of Scotland |

1,251 |

|

United Dominions Trust |

1,244 |

|

Leeds Permanent |

1,110 |

|

Hambros |

1,105 |

|

Samuel Montagu |

1,044 |

|

Woolwich Equitable |

1,048 |

|

Hill Samuel Group |

1,005 |

|

Source: Times 1000 1975/76, Tables 12, 13, 14, 15, 24. |

|

Competition does not necessarily lead to the weaker firms being

bankrupted, through there have been spectacular examples in recent

years; the centralisation of capital has been enormously accelerated

by the merger boom. Since the mid fifties more than half the

companies whose shares were quoted on the London Stock Exchange have

been taken over through their shares being purchased by other, almost

invariably larger, firms. In the peak years for mergers, 1968, £1,530

million was spent by manufacturing companies in buying up other

firms, as compared with £1,590 [million] investment in new factories. Mergers

are also an important route for giant companies expanding into

different industries, when possibilities for growth in their own

markets are limited; in 1972, another year of intense merger

activity, more than half the mergers involved moves into another industry.

The legal owners of the giant firms are the shareholders. Whilst there are around two million people in Britain who own shares, half of the shares are held by the wealthiest ¼% of the population, according to the Royal Commission on the Distribution of Wealth (Report 1, Table 31). Apologists for capitalism proclaim that there has been a ‘managerial revolution’ – that a diminishing proportion of the major companies are actually run on a day to day basis by major shareholders and that in a growing number of companies there are no longer identifiable groups of families with a controlling interest. As a result of this, they say, managers are no longer interested in profits for their own sake and can rule benevolently with an eye to the interests of workers and consumers. These trends have in fact often been exaggerated; Burmah Oil – the sixth biggest company in Britain in 1974 – is a good example of a company which despite appearances is controlled by a small group:

|

LARGE SHAREHOLDERS IN BURMAH OIL Scottish Widows Funds and Life Assurance Society |

“Scotbits Securities is a Scottish-based subsidiary of

Save and Prosper, the latter being jointly owned by Burmah’s two

merchant bankers – Robert Fleming’s and Barings – and by the

Bank of Scotland and Atlantic Assets Trust, the latter being managed

by Ivory and Sime. The Murray Johnstone trusts have had a long

association with Burmah – the company was founded by David Cargill

and developed under the chairmanship of his son, Sir John Cargill,

who was a chairman during the inter-war years of a number of trusts

managed by Brown, Fleming and Murray (the forerunner of the Murray

Johnstone group). The chairman of Burmah until 1974, now deputy

chairman, is also chairman of all the Murray Johnstone trusts.

Fleming’s Bank has long been associated with these same trusts

through the Fleming family’s association with the Murray family and

the large Scottish accountancy firm of Whinney, Murray, and the legal

firm of Maclay, Murray and Spens. Ivory and Sime manage the Scotbit

unit trusts, and through Atlantic Assets, have a large stake in Save

and Prosper. Scottish Widows Fund is interlocked through

directorships with the Murray Johnstone group (twice), the Fleming

trusts (twice), Save and Prosper (once) and Ivory and Sime (twice).

Finally, and strongest argument of all, Burmah’s board consists of

seven executive and six non-executive directors; of the latter, three

directors are also on Fleming’s trust, one is on Fleming’s bank,

one is on various Murray Johnstone trusts, one is on Scottish Widows,

and one is on the Bank of Scotland. Thus, the dominant proprietary

interests in Burmah are heavily interconnected through shareholdings,

directorships, management and other associations. The conclusion must

be that these groups do exercise influence over Burmah’s

operations ...” (Sociology, January 1976)

But in any case, capitalism throughout its history has been dominated by pursuit of profit not because of the personal greed of individual owners of firms, but because the competitive nature of the system imposes this behaviour. As Marx pointed out:

“The development of capitalist production makes it constantly necessary to keep increasing the amount of capital laid out in a given industrial undertaking and competition makes the immanent laws of capitalist production to be felt by each individual capitalist as external coercive laws. It compels him to keep constantly extending his capital in order to preserve it, but extend it he cannot except by means of progressive accumulation.” (Capital, Vol. 1)

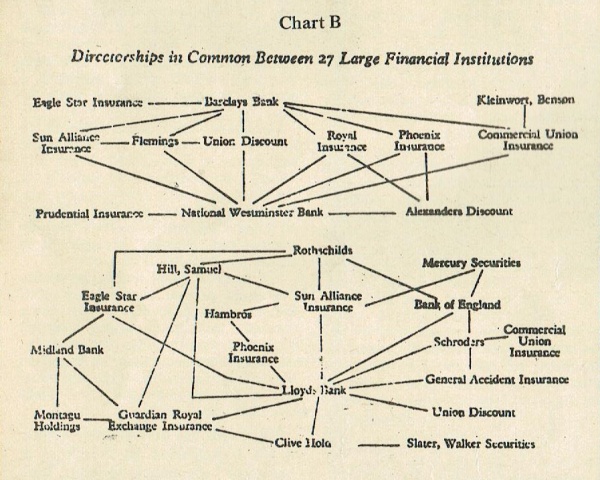

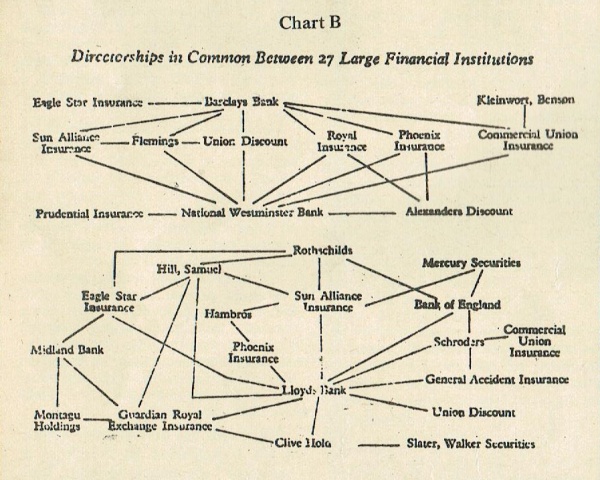

This is just as true for the chief executive of a present day company as it was of the traditional capitalist owner-entrepreneur. Even if the directors and managers hold a minute proportion of the company’s shares, their jobs, salary and prestige all ultimately depend on the success of the company, which in turn requires sufficient profits and investment. Similarly the position of the directors of the banks, insurance companies and pension funds, which together hold more than half the shares of industrial firms depend on the success of the firms in which they invest. These financial institutions are definitely in a position to ensure that their interests are taken care of; in 1970 out of the largest 50 industrial companies, 22 had directors of the clearing banks on their boards, 15 had directors of merchant banks and 18 had directors of insurance companies. There are also numerous links through joint directorships between the different financial institutions (see chart B). The cohesion of the industrial and financial sectors is further increased by links with the state – the top 50 industrial firms had (in 1960) 9 directors of the Bank of England and 5 other nationalised industries on their boards, whilst the big financial institutions had 5 directors of the Bank of England and 7 of other nationalised industries – No doubt highly useful as ‘channels of information’.

|

This also refutes the idea of the ‘democratisation of capital’, that nearly everyone now owns shares through their company pension or TU pension fund or life insurance and that we live in a ‘property owning’ democracy. On the contrary, the tremendous centralisation of productive capital in larger and large plants has been paralleled by the centralisation of control over these resources in the hands of the group of directors, chief executives and major shareholders, numbering a few thousand, who control the major companies.

|

The Top 50 Industrial, Commerical |

|

|---|---|

|

|

assets |

|

BP |

3,636 |

|

Shell |

3,109 |

|

ICI |

2,493 |

|

British-American Tobacco |

1,443 |

|

Rio-Tinto Zinc |

1,311 |

|

Burmah Oil |

978 |

|

Land Securities Investment Trust |

898 |

|

Courtaulds |

841 |

|

Unilever |

838 |

|

Imperial Group |

781 |

|

P&O Line |

750 |

|

Grand Metropolitan |

732 |

|

English Property Corporation |

787 |

|

Metropolitan Estates |

686 |

|

General Electric |

681 |

|

GKN |

626 |

|

Esso Petroleum |

621 |

|

Dunlop Holdings |

596 |

|

Shell Mex and BP |

593 |

|

Town & City Properties |

559 |

|

Bass Charington |

545 |

|

Bowater |

531 |

|

Allied Breweries |

522 |

|

British Leyland |

510 |

|

Distillers |

488 |

|

Reed International |

479 |

|

Ford Motor |

463 |

|

Rank Organisation |

460 |

|

Marks & Spencer |

413 |

|

Spears Holdings |

397 |

|

Capital and Countries Property |

393 |

|

Associated Portland Cement |

392 |

|

Great Universal Stores |

377 |

|

Rank Xerox |

376 |

|

British Oxygen |

370 |

|

British Insulated Calendar Cables |

357 |

|

Hawker Siddely |

332 |

|

Phillips Electrics |

326 |

|

Consolidated Gold Fields |

324 |

|

British Electric Traction |

323 |

|

Thorn Industries |

319 |

|

Coats Patons |

309 |

|

Tube Investments |

301 |

|

Cavenham |

300 |

|

Ocean Transport |

299 |

|

Trust House Fortes |

296 |

|

British Land |

288 |

|

Cadbury Schweppes |

287 |

|

J. Lyons |

287 |

|

George Weston Holdings |

279 |

|

Source: Times 1000 1975/6, Tables 1, 20 |

|

The activities of the Monopolies Commission, which occasionally publicises the most extortionate uses of particular monopoly power, as in the recent investigations of tranquilisers and contraceptives, and even achieves some concessions, serve mainly to divert attention from the general situation of monopoly control which they never consider.

|

The 200 Monopolies and the Financial Institutions |

|

|---|---|

|

Percentage of assets of the top 1000 industrial, commercial and property companies held by top 200 companies: |

|

|

Held by top |

% |

|

1 |

5 |

|

10 |

26 |

|

25 |

39 |

|

50 |

52 |

|

100 |

67 |

|

200 |

80 |

|

Source: Times 1000 1975/6 |

|

Perhaps the figure of 80% control can be made more real by the following list of firms in particular industries of immediate everyday significance, which would be included in the top 200 (in descending order of sales and including lists of major brand names and subsidiaries).

|

SHOPS FOOD COMPANIES BUILDING MATERIALS AND CONSTRUCTION FIRMS |

These figures do overestimate the dominance of the largest companies over the total of all companies, in that the top 1000 excludes a host of ‘small’ firms (turnover less than £13½ million); the only estimate available suggests that the largest 200 manufacturing companies produce about 60% of total manufacturing output, as compared with the higher figures quoted above. Yet the 80% figure is more indicative of the power of the giant companies, and the extent of control that nationalisation of them would give. In fact it may well understate the degree of control even for industries where small firms predominate. For many of the smaller firms, both these included in the 1,000, and the smaller ones, as well, are basically component suppliers to, or retailers for, the firms included in the top 200. They are completely dependent upon them for markets. The large firms may well find it more profitable to use their monopoly power to force down their suppliers’ prices rather than produce the same goods themselves.

Control of the motor industry (all of which is effectively

included in the top 200) would enable planning to be extended

immediately to the smaller engineering firms supplying components

(the larger firms like Dunlops, Lucas, Smiths, GKN are included in

the top 200), and also would allow control to be extended to the

smaller car distributors. Similarly ownership of the great chain

stores would allow effective government control of numerous small

producers of consumer goods (Marks and Spencers already has the

reputation for doing this in the case of many textile suppliers) even

without their immediate nationalisation. Again nationalisation of the

top 200, plus those industries already nationalised, would give

control over virtually all the major inputs of fuel, metal, chemicals

etc, and this could be used to bring smaller firms into conformity

with the requirements of a socialist plan of production.

Finally there is control of finance; at the end of 1974 there

were 25 financial institutions [excluding insurance companies] each

with capital in excess of £500 million and in total they controlled

£72 billion or more than 87¾% of the assets of the top 100

financial institutions. Nationalisation of these 25, plus the

biggest 10 insurance companies which compromise around two thirds of

the insurance industry, would give the government effective control

over the credit system. This could also be used to direct the firms

which would not immediately be taken over.

Obviously, however, it would be absurd to simply nationalise the top 200 in a mechanical fashion; the London Brick Company which lies just outside the 200 is obviously of more central importance to a socialist plan than is the Nestlé company or Consolidated Gold Fields (which operates mainly in South Africa). The list of priority companies to be nationalised would have to be drawn up on the basis of detailed information on the different industries.

The biggest 65 overseas investors, almost all of which are in the top 200, owned almost two-thirds of UK foreign investment, worth about £4,000 [million] at the end of 1971 (even excluding the oil companies assets). The way in which these assets would be used, and the 26 of the 200 companies owned overseas (mostly the USA) would be controlled, would obviously depend on the international circumstances surrounding the socialist transformation of Britain. But it is clear that nationalisation of 200 top companies, plus the 35 leading financial institutions, would give a workers’ government the control over the economic system. Only then would the tremendous centralisation of production which the dominance of the monopolies under capitalism has developed, be used for the benefit of society.

Andrew Glyn Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 3 November 2016