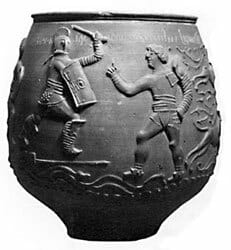

The Colchester Vase, made in Roman Britain, shows gladiators in combat

Neil Faulkner Archive | ETOL Main Page

From From Socialist Worker, Issue 1935, 22 January 2005.

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Worker Website.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for the Encyclopaedia of Trotskyism On-Line (ETOL).

Over 2,000 years ago a great slave revolt shook the Roman system of exploitation and violence. It is still inspiring for us today, writes Neil Faulkner

The Colchester Vase, made in Roman Britain, shows gladiators in combat |

A GREAT battle in southern Italy in 71 BC pitted an army of privileged citizen soldiers, commanded by a corrupt millionaire, against an army of slaves and rural labourers led by an escaped gladiator called Spartacus. It was the climax of the greatest slave revolt in antiquity.

Two years before, in the south Italian town of Capua, some 70 gladiators had armed themselves with kitchen knives, killed their guards, and escaped from their training school. They were among thousands of slaves being trained to fight to the death in the arena for public entertainment. Most were prisoners of war, victims of Roman imperialism who had been sold to slave dealers attached to the armies and then sold on to the owners of the gladiatorial schools.

Hundreds of men found themselves incarcerated in prison compounds with only a hideous death ahead.

Rome was at the height of its imperial power. It controlled colonies from Spain to Turkey, from the Alps to the Sahara. It had armies tens of thousands strong fighting at opposite ends of the empire. It was a vast war-making machine – a system of robbery with violence – in which wars were fought for the booty, slaves and tribute that could be taken from conquered people.

Ancient imperialism was different from today’s. Geopolitical competition between states and the use of force is now linked to economic competition between blocks of capital. In antiquity, the economy grew very slowly, if at all. Technology changed only in the long term. So ruling classes could not compete by accumulating capital, investing in new machinery, and producing goods more cheaply.

The struggle for surplus wealth was a “zero sum game” – one person’s gain was another’s loss because the only ways to increase wealth involved grabbing it directly from someone else. One method was to increase the rate of exploitation. Landlords could screw their peasants more. But there were important limits to this process. One was the dependence of ancient states on their own citizens to fight as soldiers in their armies. The other was the ability of these citizens to organise collective defence of their interests.

Throughout Roman history we hear of mass struggles by the common citizens against their rulers. Marx, in The Communist Manifesto, referred to the struggle between “patrician and plebeian” in ancient Rome.

The second way to grab more wealth was to take it by force from conquered people. Ancient warfare was highly profitable for the winners. The Roman conquest of Romania in AD 106 is supposed to have yielded five million pounds of gold and ten million of silver.

War also meant thousands of war-captives – not just enemy soldiers but entire populations ethnically cleansed and enslaved.

When Albania was conquered in 167 BC, 150,000 men, women and children were sold. Their abandoned farms were turned into sheep and cattle ranches for the Roman rich. It was not always so easy. Julius Caesar’s conquest of Gaul (modern France and Belgium) in 58–51 BC faced fierce resistance. At first the Gallic tribes fought piecemeal and were defeated. But the bitterness caused by the war – one estimate is that one million were killed, one million enslaved, and 800 settlements torched – put pressure on the aristocratic leaders to unite.

A great rebel confederation formed under the leadership of Vercingetorix in the winter of 53–52 BC. For the first time in history the Gauls fought as a single people, mobilising an army of perhaps a third of a million for the last great battle at the fortress of Alesia, bringing Caesar within a whisker of defeat.

Provinces won in war could later be milked of tribute to enrich the Roman state and its rulers and to buy off any risk of discontent at home. Roman citizens paid little tax, but provincials paid a property tax and a poll tax amounting to 10 or 15 percent of income.

Many, struggling on small plots and already burdened with rents, tithes and debts, faced a desperate struggle to eke out a living. Sometimes the anger boiled over.

In Palestine in AD 66–70, the Romans faced a massive revolt from below. An urban insurrection in Jerusalem was followed by a general uprising of the Jewish peasantry.

Inspired by radical preachers and organised by underground revolutionary groups who now emerged into the open, the Jewish poor were welded into a revolutionary army. Slaves were freed, debts cancelled, and property deeds torched. The revolutionaries held out in Jerusalem through five months of bombardment, assault and famine. When the city fell, the Romans consumed it with fire and sword.

It was Rome’s imperialist wars that had filled Italy and Sicily with slaves in the Late Republic (133–30 BC). Slaves soon formed a third of the population, rising to more than half in many districts. As well as working in mines and quarries, on public construction projects, in the arena and brothels, and as servants in rich households, huge numbers were used in this period to work the land.

Peasant farmers were losing out to big landlords, and when peasants were evicted, slaves replaced them.

Though slaves came from all parts of the empire, many were from the eastern Mediterranean, and the Greek that was spoken there became the language of slaves generally.

Many slaves were educated or were former soldiers.

Rome and Italy, moreover, were racked by internal conflict. The conditions were ripe, then, for slave revolution. The leadership of Spartacus was its trigger.

We know little about him – a few pages in each of two Greek historical works. But there are clues here to the character of his revolt. Poor freemen fought alongside the slaves. Captured spoils were equally distributed. And an embryonic revolutionary state emerged in southern Italy, with official storehouses, arms factories, and tight collective discipline.

After escaping from Capua, the gladiators had first taken refuge on Mount Vesuvius. From here, they raided aristocratic estates and freed the slaves. As the news of their exploits spread, others came spontaneously to join them. And when it was known that slaves had beaten Roman soldiers the trickle of recruits became a flood.

In the following year, 72 BC, the whole of Roman Italy was convulsed by slave revolution. Tens of thousands marched with Spartacus, and a succession of Roman armies were crushed. But there were splits over strategy. Should the slaves break out over the Alpine passes and disperse to their various homes?

Or should they go south and spread the revolution to Sicily where there had been two great slave revolts within living memory? Or should they march on Rome itself and try to bring down the whole slave empire?

Meantime, after their defeats of 72 BC, the Romans had appointed Marcus Licinius Crassus to a special supreme command in Italy, giving him 65,000 men to suppress the revolt.

For six months, Spartacus evaded Crassus in a skilful war of manoeuvre. But by the autumn of 71 BC, the rebel leader found himself trapped in a mountain stronghold in southern Italy. Caught in a vice of converging armies, the slaves now faced the whole military might of the Roman Empire.

Spartacus led the slaves out to their final battle. The historians record that it was bitterly fought, and that Spartacus, having killed his horse beforehand as a precaution against flight, died trying to hack his way through to Crassus himself. His body was never found.

The remnants of his army were pursued into the mountains. Some 6,000 captives were later crucified along the Appian Way, the road that ran from Rome to Capua, where the revolt began.

Spartacus became a folk hero for ancient slaves. He has been an inspiration ever since. Marx described him as “the most splendid fellow in the whole of ancient history”, and the early German communists called themselves the Spartacus League. He is an inspiration still, for today’s anti-capitalist and anti-war movements are his political heirs.

Rome is held up as a model of civilisation. It was nothing of the sort. A system of exploitation and violence, it provoked the most furious resistance from those it oppressed. But because its enemies were never united, each struggle was eventually defeated. The lesson for us, in an age of imperialism and war, is not only that empires can be resisted, but that if they are also to be defeated, resistance must be global.

Neil Faulkner’s latest book, Apocalypse, is available.

Neil Faulkner Archive | ETOL Main Page

Last updated on: 10 February 2022