Publications Index | Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’s Internet Archive

Socialist Review Index (1993–1996) | Socialist Review 174 Contents

Socialist Review, April 1994

Briefing

Children’s rights

Spare the rod

From Socialist Review, No. 174, April 1994.

Copyright © Socialist Review.

Copied with thanks from the Socialist Review Archive.

Marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

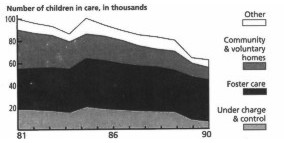

Type of accomodation for children in care

|

- Last month the High Court upheld a childminder’s right to

smack children in her care. Yet article 19 of the United Nations

Convention on the Rights of the Child, ratified by the British

government in 1991, obliges states to prevent physical violence to a

child by parents and carers.

- Smacking and other forms of corporal punishment have been

illegal in British state schools since 1986. Children from five

years upwards are protected by law from being hit by professionals –

pre-school children are not. If an adult were treated in such a way

the assailant could be charged with assault.

- Child psychiatrists, other health professionals,

educationalists and the vast majority of childminders are against

smacking, purely because there is no evidence to show that it helps

in disciplining children.

- Claire Rayner, the popular ‘agony aunt’, is a vocal

opponent of smacking. She feels that ‘hitting children to

discipline them just makes them angry and resentful. People do it

because they think it’s quicker and easier than teaching the

child.’

- Most local authorities in Britain expect their childminders

to refrain from smacking, and have introduced guidelines and

training courses to deal with issues of discipline. However there is

no legislation to prevent childminders smacking children in their

care.

- The Children Act which came into force in 1991 says

that a local authority can refuse to register a childminder if they

are ‘unfit’. Specific guidelines, including those on corporal

punishment, are not legally part of the act, so they allow a

loophole to the judges to uphold the right of childminders to

smack.

- The Children Act is based on the notion that

children’s welfare must come first. Yet subsequent laws such as

the Child Support Act, the Education Reform Act, and

the locking-up of 12-year-old offenders have clearly gone against

this principle.

- We are often presented with the assumption that children

have ‘never had it so good’. This could not be further from the

truth. Many of today’s children live in conditions worse than

those of the workhouses of Oliver Twist’s time.

- A recent National Children’s Home survey showed that for

over 1.5 million families on income support, only £4.15 a week is

allocated for food per child. This compares with weekly food

allowances in workhouses of the equivalent of £7.07 per child in

the early 1900s and £5.46 in the 1870s.

- Evidence from the National Children’s Bureau shows that

there has been a huge increase in child poverty since 1979. A recent

government report shows that nearly one in three children in Britain

live in a family receiving less than half the average income. Linked

to this poverty are poor health, unsatisfactory housing and

inadequate educational opportunities.

- One in four children in London eat free school meals

because of poverty. At school some children are unable to

concentrate because of hunger, and teachers take in biscuits to feed

their pupils.

- Poor child health is related to poverty, malnutrition and

bad housing. The legacy of childhood illnesses often lasts

throughout adult life. There has been an alarming increase in

childhood asthma and other respiratory diseases particularly related

to damp housing. Diseases related to chronic malnutrition, together

with tuberculosis and rickets, are also making a comeback among

children in Britain.

- Depression in childhood has been acknowledged only fairly

recently. A survey published by the YMCA last month found 64 percent

of teenagers questioned in Brighton had felt depressed at some time.

The same study also found 58 percent of teenagers questioned had

used illegal drugs.

- Children who suffer from neglect and abuse, or are

considered ‘at risk’, are put on Child Protection Registers.

Almost 50,000 children were placed on these registers in England and

Wales during 1990. This works out at 3.7 per thousand children

nationally. Comparing this figure with regional ones of 17.5 per

thousand in deprived Southwark, south London, and 3 per thousand in

nearby, but more prosperous, Bromley, we see some indication of the

way poverty can affect families.

- In Strathclyde a fivefold increase in children registered

as physically abused over five years in the late 1980s was directly

attributed to an increased level of poverty in the region during the

previous decade.

- The Children Act sets out that disadvantaged children

should have their needs met by services provided for them by local

authorities. Government cuts have meant new services are few and far

between and existing ones are overstretched and underfunded.

- There is a massive demand for services that allow children

to talk about their problems. Childline, a charity set up in 1986 to

provide 24 hour telephone counselling, receives 10,000 calls every

day, of which about 3,000 can be answered and only 200 to 300 dealt

with in any depth.

- Teenagers surveyed in Brighton showed scepticism about

local services – with lack of confidentiality, lack of

understanding and poor availability being the major failings. One

16-year-old wanted services ‘just to be sympathetic to the needs

of today’s young people, and understand when they feel stressed

out about unemployment etc.’

Top of page

Socialist Review Index | ETOL Main Page

Last updated: 10 March 2017