Mexico’s Missing Students

New witness account undermines Mexican Government narrative of missing students

At the end of the night of September 26, 2014, in the Mexican city of Iguala, it rained. The lifeless bodies of Daniel Solís and Julio César Ramírez, two students from a rural teachers college in the nearby town of Ayotzinapa, lay drenched on the asphalt. No one had been able to help them. Their classmates, who had traveled to the town to steal buses to drive to a political protest, had run off in terror as an unidentified shooter opened fire. Everyone tried to escape the chaos at the same time, but Daniel and Julio didn’t make it.

The authorities arrived around 3:20 A.M. on the morning of September 27, 2014, about three hours after the killings, to take away the bodies and gather evidence from the corner of Juan Alvarez and Periférico streets. Reports written by forensic experts leave no doubts about the severity of the violence inflicted against the students, who only had rocks to defend themselves. Three buses had been shot up and dozens of empty rounds lay on the ground, along with a fragment of a finger, pools of blood and leather sandals. Their owners were either dead, hiding or disappeared.

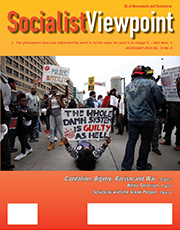

Tens-of-thousands of Mexicans have gone missing in recent years, but the disappearance of the 43 Ayotzinapa students has become a rallying point for much of the Mexican public, and provoked the most serious political crisis for the federal government in decades. Once the darling of the international media, President Enrique Peña Nieto saw his domestic approval rating and his image abroad plummet because of repeated accusations that his administration mishandled the investigation into what became of the 43 students.

As dusk fell on September 26, a group of more than 100 Ayotzinapa students traveled toward the city of Iguala to commandeer buses, a common tradition among the state’s leftwing college pupils, who often use them to go to political protests. That night, after taking the buses, the students were attacked three times. The first one was at 9:40 P.M., when the municipal police fired shots into the air. Then around 10 P.M., the students were shot at by both the municipal police and the federal police. In the third attack, around midnight, the students were once again shot at, this time by a group they could not identify.

By the end of the night, three students and three bystanders had been killed, more than 15 students had been wounded—and 43 had been abducted.

Eight months have passed since then, but more questions than answers remain about what happened that night. Federal prosecutors, whose case rests partly on confessions that appear to have been given during torture, allege that Iguala Mayor José Luis Abarca ordered the attacks on the students to prevent them from disrupting a political event for his wife, María de los Ángeles Pineda. (In fact, the political event that night ended two hours prior to the first attack.) They say local police took the 43 missing students from Juan Alvarez Street in Iguala, where the violence took place, and brought them to the Iguala police station at 11:30 P.M. From there, the federal attorney general’s office says two police patrol trucks from the nearby municipality of Cocula carried the students away, to be handed off to the drug gang Guerreros Unidos, who prosecutors say killed the students and incinerated their bodies in a dumpster in Cocula.

But a magistrate judge who spent the entire night of September 26 in the Iguala police station offers a completely different account. In an exclusive interview as part of an investigation supported by the Investigative Reporting Program at the University of California, Berkeley, former Magistrate Judge Ulises Bernabé García describes what he says really happened in the Iguala police station that night. It’s the first time a member of the security forces present at the police station that night has spoken publicly about what happened there—calling into question the government’s official investigation.

What we know about the events of September 26: A timeline

Bernabé García worked in the municipal police station in Iguala through the night when the 43 students from the rural teacher’s college of Ayotzinapa disappeared, and into the next morning. Speaking in a Mexican border city before crossing into the U.S. to ask for asylum, he said the missing students were never brought to the station, and police from neighboring Cocula never visited the station either, as the Enrique Peña Nieto administration claims.

Bernabé García says that at the time when the federal attorney general maintains the students were brought to the Iguala police station, a captain with the 27th Infantry Battalion was at the station with a group of soldiers. Shortly after that, Guerrero State assistant Attorney General Víctor León Maldonado arrived and took control of the station. If the students had been there, Bernabé García says, the army and the state attorney general’s office would have seen them.

Furthermore, he says, it would have been difficult to transport that many students into the police station in the first place.

“Let’s consider the fact that the students don’t fit in the squad trucks, much less with the police in there too,” Bernabé García said. “It’s not logically possible, right? Did the police officers walk behind the squad trucks?”

The transfer of the students to the Iguala police station is a key link in federal prosecutors’ case against the local government, and one that distances the state and federal government from the attacks and abduction. Removing that link leaves a gaping hole in the version of events offered by federal and Guerrero state authorities. Without it, we don’t know who took the 43 students, when it happened or where they were taken.

Bernabé García testified before federal prosecutors on November 21, who then sent him home. Shortly after that, the military went looking for him. Police from the neighboring town of Chilpancingo tried to find him at his home, where he lives with his mother. Bernabé García wasn’t there, but several of his family members were.

“They entered illegally, they didn’t have a warrant or anything,” he said. “They went in, drew their weapons in front of my family—my mother, my sister who was at the house at the time, my nephews who are seven and nine-years-old. In front of another nephew, who’s five-years-old, they drew their weapons.”

On January 15, 2015, the federal attorney general’s office issued an arrest warrant for his alleged participation in the kidnapping of the students and for alleged connections to organized crime. Fearing for his safety, he fled to the United States and filed a petition for asylum. U.S. authorities routinely detain asylum seekers while their cases move forward in the courts. Since April 20, he’s been stuck in an Arizona immigrant detention center.

A key witness comes forward

Bernabé García, 29, started working for the local government in Iguala five years ago, focusing on rural development. During local elections in 2012, he served as a personal assistant to the Institutional Revolutionary Party candidate for mayor, Eric Catalán. Catalán lost the 2012 election, and two months after the next mayor, José Luis Abarca, took office, Bernabé García asked to be transferred to the municipal police to avoid being fired. He took a job there as a legal consultant.

In July of last year, the magistrate judge took a leave of absence and Bernabé García temporarily took over the job. His job mostly consisted of writing tickets and handing down jail time for administrative offenses: public intoxication, disturbing the peace, urinating in public. He was scheduled to return to his old job on September 30.

“What happened to me was bad luck more than anything,” Bernabé García said.

His name is mentioned in investigations opened by both the state and federal attorney general’s offices, which accuse him of interrogating the students in the police station and then handing them over to Cocula police. He paints a different picture.

Bernabé García says only six detainees entered the police station the night of September 26. All were between 30 and 35 years old, and all of them were arrested for drinking in public. Each one received a ticket and was placed in a holding cell. The last one arrived around 9:30 P.M.

Bernabé García’s version checks out against testimony offered September 27 by local police, who said only six people had been detained that night—one was arrested near a bakery, while the other five were arrested while driving drunk.

Meanwhile, the students left Ayotzinapa about 6:00 P.M. in two buses and arrived in Iguala two hours later. By the time they entered the town, they were already being monitored by state and federal police. At the bus station, the students began to commandeer additional vehicles. At 9:40 P.M., after the students had taken three buses and left the bus station, police near them shot into the air. The buses continued on their way, followed by police. Sometime between 10:00 and 11:00 P.M., the three buses turned onto Juan Alvarez Street, which was being blocked from the front by municipal police. As the students’ buses were trapped by the police near the road’s intersection with Periférico, they were shot at once again. In depositions and in videos they recorded during the attack on their cell phones, the students identified both the federal and municipal police.

By 11:00 P.M., the police had left, and the survivors called the press and their friends for help.

A visit from the military

Bernabé García said he didn’t find out about the attack right away because as an administrator, he didn’t have access to police communications equipment. Around 11:30 P.M., the police officer guarding the station’s front door came to tell Bernabé García that a military officer wanted to see him.

The military already knew about the attacks on the students, but the captain entered the station, accompanied by five men, all armed and in uniform, under the pretext of looking for a white motorcycle. He inspected every corner of the station: cells, bathrooms, offices. The six drunk detainees were still there. None of them were students from the Ayotzinapa teacher’s college.

He identified himself as “Captain Crespo.”

“It was the first time I’d seen him and it felt a bit suspicious because he patted me on the back,” Bernabé García said. “He talked as if we knew each other. I gave him all the freedom he wanted: ‘You can search the station.’” The inspection lasted about fifteen minutes. Then Crespo left.

Shortly after 11:00 P.M. that night, some students gave a press conference on the corner of Juan Alvarez and Periférico streets, where the initial attacks had taken place. Around that time, a truck carrying local soccer players—who some believe were confused for Ayotzinapa students—were assaulted by unknown gunmen on the Iguala-Chilpancingo highway. Three people died and several others were injured.

Then around midnight, as the students and journalists gathered for the press conference, an unidentified group of people opened fire on them. It was this third attack that killed Daniel Solis and Julio César Ramírez. The next morning, another student, Julio César Mondragón, was found dead a few kilometers away, with skin torn from his face.

Students and their attorneys say some of the students were abducted during the second attack, and others were taken while fleeing the third attack.

Around midnight, several students fled to Cristina Hospital, a few blocks away from the shooting, according to a deposition taken from surviving student Francisco Trinidad Chalma. They brought a student who had been shot in the face. The army followed.

“The [person] in charge of those [military] units asked if we were the Ayotzinapa students looking for help for our friend who was bleeding profusely, and he told us that we’d ‘have to have balls to face this situation, just as you had the balls to make this goddamned mess,’” Trinidad Chalma’s statement says. “They searched through the whole clinic…looking for weapons, but we weren’t armed.”

Another student, Omar García, said in an interview that the military arrived quickly. “They came in, cocked their guns as if they were—I don’t know—facing criminals. They accused us of breaking into the hospital. [They said] they were going to take us all, because we were criminals.” The officials took photos of the students and asked them to give their real names, saying that if the students lied, the officials would find them anyway.

Mexico’s 27th Infantry Battalion filed at least four reports detailing what happened, which were obtained by journalist Marcela Turati. In two of the reports, the battalion omitted all the activities of the military. But in another two, they acknowledged that groups of soldiers, including Captain José Martínez Crespo, were in the streets of Iguala from 11:20 P.M. until 5:20 A.M. the next day—when the worst violence occurred. They also noted that Martínez Crespo went to the hospital where the students had fled with their badly injured colleague. Yet in the first days after the attack, the federal government denied the military was in the city at all that deadly night.

The Attorney General’s Office takes control

According to Bernabé García, after the military’s visit, Iguala’s head of public security, Felipe Flores, visited the police station with Guerrero Assistant State Attorney General’s Víctor León Maldonado. They saw who had been detained, and gathered together the staff. They said shots had been fired against the students and asked the municipal police to hand their guns over for forensic tests.

The Assistant Attorney General left, but the police station was left under the control of the state attorney general’s office. Around that time, family members of the people detained in the drunk tank began arriving.

“They gave me their names and paid their fines, the minimum,” Bernabé García said. “In that moment, they’d already told us what happened,” he added, referring to the authorities who had visited the station. The last detainee left at 2:20 A.M. When the Assistant Attorney General returned, he was irritated that those arrested for public intoxication had been released, though Bernabé García says he wasn’t told they should be held.

To try to quell the Assistant Attorney General’s anger and to cover his bases, the ex-magistrate judge said he then showed him the tickets documenting that the detainees were booked and released, and that days later he also submitted a report to both the state and federal attorney general’s offices with copies of the tickets.

The morning of September 27, local police gathered at the state police station. “They sent me directly to the Assistant Attorney General and asked me, ‘Where are the students?’” Bernabé García said. “What students? I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he says he answered.

León Maldonado then insisted that students had been at the station, which Bernabé García denied. Bernabé García then wanted to testify to prove he wasn’t lying, but the police didn’t take his statement. They didn’t detain him either, so he went home.

According to the Guerrero attorney general’s investigation, Iguala police officer Hugo Hernández Arias accused Bernabé García of holding the students in the police station’s patio, though documents indicate the testimony appears to be altered. Hernández Arias’ first deposition doesn’t mention the students or Bernabé García; a later copy of the deposition included in the investigation is the same word for word, with two additional questions at the end in which Hernández Arias implicates the magistrate judge. Hernández Arias had never returned to elaborate on his testimony.

Unanswered questions

How the 43 students disappeared still remains a mystery to their mourning families, who are demanding answers and accountability. In October, the federal attorney general’s office arrested police officers from Cocula, accusing them of participating in the disappearance of the 43 students. Eleven of them testified that they had been involved in arresting the students, but the testimonies contradicted one another regarding the time, manner and other details on how the students were taken.

Medical reports, which in Mexico are taken routinely in criminal investigations when police or military officials transfer suspects or witnesses to prosecutors for questions, showed signs of torture—burns, scars, bruises from beatings and red marks revealing electrocution.

In May, the head of Iguala’s police force, Francisco Salgado Valladares, was arrested. He testified before federal prosecutors that the students were brought to the station at 10:00 P.M. the night of September 26, despite that his testimony contradicts the federal attorney general’s own public statements.

Moreover, Bernabé García continues to deny that he ever interacted with the students or had anything to do with their disappearance. If the accusations against him were true, he says, other police officers and administrative personnel at the station would have also testified that the students had been there, because the patio where they were held is in the middle of the station. All of the offices have windows that overlook the patio, which reporters confirmed during a visit to the station. The military and officials from the state attorney general’s office would have seen the students too.

Repeated attempts to locate or interview then-Assistant Attorney General León Maldonado, who left his job in April according to his Facebook account, were unsuccessful. A representative of the 27th Infantry Battalion said Cpt. Martínez Crespo continues to work there, but he did not respond to an interview request. The federal attorney general’s office also declined to comment about Bernabé García’s statements.

“They’re after me because I’m telling the truth”

Since December 2014, Bernabé García has been on the run because he fears that if Mexican authorities arrest him, they will “disappear” him or torture him, like they tortured his colleagues.

“I can’t invent something that never happened,” Bernabé García said, in what are his first public remarks. “At what time could [the students] have arrived if the military was there at 11:30 P.M. to inspect the area? They didn’t find anything.…If the students had been there, they would have known.”

Bernabé García knows his police department colleagues were forced to give depositions under torture, but he fears for the security of his family more than he fears for himself.

“Let them say, ‘The magistrate is talking about things that did happen, that the army came to inspect the station,’ and let them leave some space to admit that maybe they had something to do with it,” he said. “I’m not saying they did have something to do with it, but I’m showing the proof that they were out [on the streets] that night, because they were saying that they were not.”

Bernabé García says he’s been an honest man his entire life.

“It is sad that they accuse me of being a criminal,” he said. “I am simply telling the truth as it is.”

And he finds it gut-wrenching to watch grieving parents search for their disappeared children. “But it pains me more that they’re blaming me when I didn’t have anything to do with it,” he said, “while those who might be responsible for it are walking freely on the streets.”

A version of this story was published Sunday, June 14, 2015 in Spanish in the Mexican magazine Proceso.

Anabel Hernández is a leading Mexican journalist who has covered politics and organized crime for two decades. She is the author of Narcoland: The Mexican Drug Lords and their Godfathers, a ground-breaking rethinking of the people and politics driving Mexico’s drug war.

Steve Fisher is an investigative journalist who focuses on immigration and the relationship between the United States and Mexico. Last year, he produced the award-winning documentary “Silent River,” which follows a family’s efforts to combat the contamination of one of Mexico’s most polluted rivers.

Both Hernández and Fisher are fellows at the University of California, Berkeley’s Investigative Reporting Program, which has sponsored their reporting on the disappearance of the 43 students.

—The World Post, June 14, 2015

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/14/disappeared-students-mexico_n_7574652.html