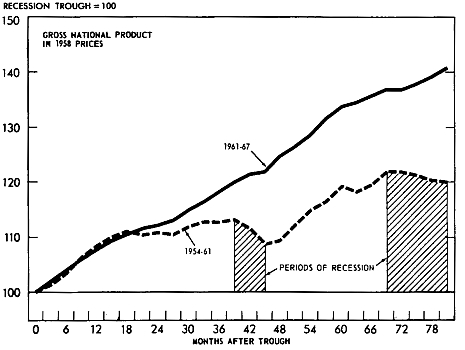

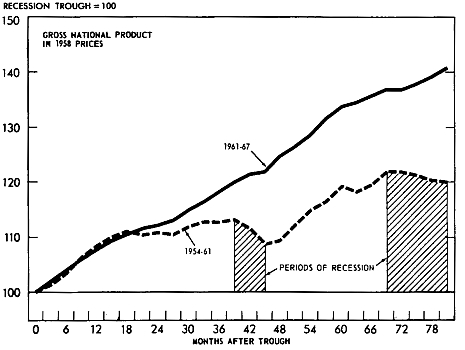

Real Gross National Product After the Recession Troughs

of 1954 and 1961

ISR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

From International Socialist Review, Vol.30, No.5, September-October 1969, pp.35-55.

Transcribed & marked up by Einde O’Callaghan for ETOL.

|

This autumn will mark the 100th month of expansion of the US economy. It is the longest “boom” in US history and one of the greatest capitalist expansions of all time. The “Keynesians” in Washington – economic advisers to the White House, the Treasury Department, the Federal Reserve Board – take credit for the expansion and some even claim they can do it again. Combining “fiscal” measures, that is, policies of taxation, and “monetary” measures, policies which regulate the money supply, they claim to be able to regulate the economy as though it was a tub of water and they controlled the faucet: now pouring money in to make the economy expand, now turning the money supply off to make the economy contract This article examines the actual record of fiscal and monetary policies in the sixties. It compares the “miracle” of the sixties with the “stagnation” of the fifties. The assertions, the facts and the figures of the Keynesians are from their own writings, official and unofficial. |

* * *

On June 30 the US House of Representatives voted by a narrow margin to continue the 10 per cent tax surcharge on incomes imposed by the Johnson administration in 1968, and to discontinue the investment tax credit for corporations dating back to the Kennedy administration (but temporarily suspended in 1966-67). These two measures are strong restrictive medicine. If they now pass the Senate, they will constitute an important further step toward “cooling off the economy,” that goal so fervently desired in US ruling circles but so difficult, it would seem, to attain.

The House debated this bill under “closed rules,” thereby limiting the discussion to four hours. It could hardly be described as a pleasant session for the Congressmen on either side. The President, who promised to repeal the unpopular tax surcharge in his campaign and told businessmen he wouldn’t tamper with their investment tax credit, had been haranguing House leaders for three weeks about why he changed his mind on both points. They had met with top economic advisers and representatives of banking and industry.

“We have not had a real recession in this country since 1937,” Congressman Bolling, a member of the Joint Economic Committee since 1951, explained. “Do not kid yourself ... We have the greatest economic skew today that we have ever had, and the fault is bipartisan and I am not going to lay the blame here ... No one knows what will happen if this measure is voted down. Do not take the chance.” House Republican leader Gerald R. Ford recalled the pressure that had been exerted by the Johnson administration:

“We sat there at the White House and Mr. William McChesney Martin [Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board] made one of the most dramatic pleas that I have ever heard a person make for an affirmative action in a crisis. Mr. Martin pointed out ... that unless we stood up and passed the surtax, we as a nation faced the distinct possibility that there would be something comparable to the depression of the 1930s ...”

The men who had voted themselves a pay raise of $6,687,500 a few months earlier and who know that the real wages of most Americans have been declining because of the war-primed inflation, were understandably reluctant to vote a tax increase, even in order to curb the inflation. The final tally was 210 for, 205 against Unity in the face of adversity is not a high-ranking virtue of capitalist politicians.

But the dangers facing the American economy are real and apprehension about the future is growing from day to day. When Secretary of State Rogers suggested a week later that wage and price controls might be necessary if the tax surcharge law was not passed in the Senate, the stock market plummeted 35 points to a low for the year.

Since December 2, 1968, prime interest rates have climbed in five successive leaps from 6.25 to 8.5 per cent, the highest interest American banks have ever charged to major corporations. Consumer prices rose 4.8 per cent in 1968 and are rising at a rate of close to 6 per cent in 1969. In the single month of March they rose at an annual rate of 8 per cent “To allow the surcharge to lapse,” the Mellon National Bank and Trust Co. warned June 27, “would serve to perpetuate and prolong the inflationary spiral and drive interest rates even higher. Furthermore, the psychological impact of abandoning even this modest measure of fiscal restraint could touch off a disruptive boom and bust cycle of business activity and trigger a worldwide loss of confidence in the integrity of the dollar with ominous implications for the expansion of world trade.”

It is becoming increasingly evident that the economic advisers in Washington have lost the reins on the economy they seemed to have four and five years ago. Even as late as 1967, when a combination of tight money and increased taxes had slowed the economic upsurge of 1966, the Council of Economic Advisers (Gardner Ackley, James S. Duesenberry and Arthur M. Okun) declared:

“The main lesson is clear from the record: economic policy was used effectively to restrain the economy during 1966, much as it had been used during the preceding five years to stimulate demand.” (Annual Report, p.50)

But the slowdown they produced in mid-1966 threatened to turn into a recession in 1967, a course that had to be ruled out at a time when the war was still escalating and there had already been several summers of stormy black protest The reins were eased and the economy resumed its frenzied inflationary climb. The Annual Report of February 1968 lacked the air of certainty of one year earlier. Now the economic advisers wanted an immediate tax surcharge as the “first order of business in 1968” to “promote the balance of payments ... The task of decelerating price and cost increases and of gradually restoring price stability,” they said, “is a key assignment for economic policy in 1968.” (p.39.)

But Congress did pass the tax surcharge hi 1968 and there were some who voted for it then who were no longer on Capitol Hill a year later to reconsider the question. The measures that were supposed to “decelerate” price inflation and “avoid” credit stringency seemed to end up accelerating price inflation and pushing interest rates to their all-time high. The economy of 1969 was in worse straits than the economy of a year earlier. And the same economic specialists were telling Congressmen to do the same thing, only more so.

In order to understand the mechanisms that have pushed the US economy into this contradictory state of affairs and to understand the course the Nixon administration is undertaking, it is necessary to review the main tendencies of the US economy in the past eight years – in the famous “boom of the sixties.” This is particularly worthwhile because the course the administration is following is recessionary. For all their claims to the contrary, the directors of economic policy in Washington have once again decided that economic slowdown and unemployment is the only solution to their problems.

The first 80 months of the boom are depicted below in a chart reproduced from the 1968 Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisers, p.60. This calls attention to the most significant differences between the economic upturn that began in 1961 and the two previous cycles which began in 1954 and 1958. Whereas the Eisenhower administration had responded to each real or potential price inflation by severely restricting credit and ultimately inducing a recession, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations followed a policy of easing credit even while the government was running budget deficits. Keynesian economists take credit for the wisdom involved:

”All five members of the council [in 1961 when Kennedy took office: Walter Heller, James Tobin, Kermit Gordon (the latter two were later replaced by Gardner Ackley and John Lewis)],” Seymour Harris wrote, “believed in Keynesian economics. They therefore, above all, sought adequacy of demand. That is, when the private economy is foundering because the goods being produced are not being taken off the market at profitable prices and, hence, output falls below the potential – at such times the government should intervene through increased public spending (and) or reduced taxes. The objective of their economic policy is a balanced economy, not a balanced budget.” (Economics of the Kennedy Years, 1964, p.22)

|

Real Gross National Product After the Recession Troughs  |

|---|

Much as has been made of this philosophy, a closer look at the economic realities of the early sixties convinces one that the choices made by the Kennedy administration corresponded to the needs of US monopolies. Furthermore, as the sixties progress, it becomes evident that the contradictions of the world market and the cost of driving back the colonial revolution overtaxed the ingenuity of the economic specialists. The contradiction between the needs of monopoly and the capacity of markets explains the present economic impasse, not any good or bad choices by economists. And finally, even a cursory glance at a few other statistics for the period shows how the Keynesian “miracle” actually operated – by taking money out of the pockets of workers and putting it into the hands of the corporations. Between the first quarter of 1961 and the fourth quarter of 1968, corporate profits after taxes increased 109.8 per cent, 10-4 per cent per year; per capita disposable personal income Increased 32.7 per cent, 3.7 per cent per year. In terms of real purchasing power, the figure for weekly paychecks in June 1969 is $2.24 below the figure for last September and below the yearly averages for each of the last four years.

’The major forces of the economic history of the sixties have been the imperialists’ need for profits on a domestic and international scale, in the context of the growing challenge of Western Europe and Japan, and the war in Vietnam. Next to these, the labor of the Keynesians has been entirely secondary. To prove this it is necessary to go back to the days when the Kennedy administration took office.

Kennedy considered that one of the central economic problems facing his administration was the persistent balance of payments deficits which had averaged more than $3 billion a year since 1958: “ The United States must, in the decades ahead, much more than at any time in the past, take its balance of payments into account when formulating its economic policies and conducting its economic affairs,” one of the first state papers of the new president declared, February 6, 1961. It had been the Eisenhower administration’s attempt to combat negative payments balances through tight money policies that ended up with the 1960-61 recession.

How could the dollar be protected without incurring a recession?

Even more important, why is the balance of payments so crucial to the US economy that the Republicans were willing to risk, and actually incurred, a recession in order to achieve a favorable balance? The question is fundamentally one of imperialist domination in the world market The negative balance of payments stemmed from the fact that throughout the postwar period, the US spent more dollars abroad than these investments returned and than foreign nations spent in this country. US dollars went to stabilize the war-wracked European and Japanese economies and to finance a worldwide network of military bases. At the same time US monopolists purchased whole sectors of foreign industry, not only in the underdeveloped world but in Europe as well.

The Bretton Woods agreements of 1944 made the dollar supreme in the world monetary system. According to the “gold-exchange standard” that was adopted, the dollar would back international currencies and the dollar itself was backed by the huge stockpile of US gold in Fort Knox. The US guaranteed mat it would exchange gold for dollars with foreign central banks. Only the dollar was so privileged. This system obviously gave US imperialism the upper hand, since it manufactured dollars – and.dollars were “as good as gold.” Wall Street flooded the world capitalist market with US goods and dollars.

For a long time, until the late fifties, the United States was not immediately concerned with the balance of payments because of its large positive balance of trade. US firms were able to sell more American goods in foreign markets than the American market absorbed in foreign goods. The do liars that flowed out in foreign investment and military expenditures flowed back in world trade.

But this overwhelming US advantage in world trade and the big stockpile of gold in Fort Knox have been undermined and depleted by the resurgence of the European and Japanese economies beginning in the mid-fifties. The imperialists abroad began to fight “dollar diplomacy” (the exception, of course, being Britain, whose dependency on the dollar rules out any consideration of rebellion). Foreign governments put pressure on Washington by turning in their dollars for gold.

The question of the balance of payments was consequently a question of the test of strength of US imperialism, that is, a question of the stability of the world monetary system backed by the dollar.

Eisenhower was willing to go so far as sacrificing domestic expansion to protect the international position of the dollar. By tightening the money supply and thereby forcing banks to raise interest rates, the Federal Reserve Board could make investment in the US more profitable for foreign capitalists. The inflow of their investments would provide Washington the counterweight to the flow of dollars abroad. This technique actually worked in 1968, as is described below, but in the Eisenhower years, the imposition of tight money strangled domestic expansion without improving the balance of payments. The prospect of a recession does not attract foreign investment.

The balance of payments was already in trouble. But the more far-sighted capitalists (including Kennedy himself and some of his advisers) saw bigger troubles approaching. In 1960, the US trade surplus was $3.8 billion; in 1961, $5.4 billion; in 1962, $4.8 billion; and in 1963, $5.3 billion. This was hardly a steady march forward. A parallel set of figures led to even more pessimistic conclusions: the declining US share of world exports.

Writing in 1963, Seymour Harris noted that

“from 1953 to 1962 the United States share of world exports of manufactures among highly industrialized countries dropped from 26.2 to 19.9 per cent Only the United Kingdom had an equally bad record ... An examination of US exports of all commodities reveals similar disappointments. From 1953 to 1962 despite the upward relative trends for industrialized countries, US exports dropped from 21.8 per cent of world exports in 1953 to 17.4 per cent in 1962.” (Economics of the Kennedy Years, p.160 ff.)

Harris blamed it on “relative rises in productivity [abroad] related to a changeover to larger scales of production; great expansion of capital which was, in turn, associated with the import of American capital; and substantial advances in technology, again tied to increased recourse to large-scale output and to American technology. A large part of the explanation of our losses,” he added, “lies in the considerable advance in Western Europe in a relatively few industries, such as automobiles and iron and steel ...” Harris, who was senior consultant to Secretary of the Treasury Douglas Dillon, concluded, “the crucial problem is the United States competitive position, an improvement in which should increase the excess of exports over imports.”

The Kennedy administration ruled out a tight-money-followed-by-recession course of righting the balance of payments. A recession would further retard the needed technological advance. US industry was on “dead center” – in the vernacular of the period – and Kennedy wanted to “knock it off.” Secretary of Labor (!) Arthur Goldberg told a National Press Club audience in 1961, “around $75 to $90 billion of our plant and eq”ipment is obsolete ... We must regain our pre-eminence in this field, using the tax system if necessary.”

Two important tax measures were adopted in 1962 to stimulate business investment: Depreciation rules were liberalized and an investment tax credit of 7 per cent on machinery and equipment was enacted. These were long-range benefits to corporations. Over time, capital investment began to increase. By 1964 a new drive toward technological superiority in world trade was underway in US industry – a drive that will now letup only in recessionary periods. The capital-investment boom of 1964-65 was further stimulated by direct corporate and income-tax reductions, which Kennedy had proposed in August 1962, but which were delayed in Congress until February of 1964.

A final and decisive impulse to business investment, pushing the expansion into 1966, came with the massive escalation of the war in Vietnam. This provided markets for war materiel But it was also a spur towards non-war-goods investment because it “virtually assured American businessmen that no economic reverse would occur in the near future,” in the words of the 1967 Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisers (p.46).

Kennedy’s tax program was difficult for some Congressmen to swallow because it forced them into the open as supporters of big business at a time when Democrats could still claim some distinction between their policies and those of the Republicans who brought on two recessions. Kennedy had gone so far as to promise “tax reform.” This sticky issue is worth examining briefly because it has come up again in the present Congressional tax dispute. US income taxes, which are supposed to be graduated as to income levels, are notoriously contrived in order to benefit the wealthy. In the June 30 debate on the tax surcharge in the House of Representatives, one Congressman asked,

“When there are 155 people with $200,000 incomes who do not pay taxes – why should the ordinary taxpayer not rebel? When he reads about 21 millionaires who do not pay taxes, I can understand his fury. When the 22 largest oil companies pay only 85 per cent on their $6.8 billion profits, I see the discrepancy. When a person earns between $5,000 and $15,000 annually and pays 30 per cent of it for taxes, I can understand the resentment”

There was good cause for resentment among some Kennedy supporters. One of them wrote in 1964,

“The fact that Kennedy gave a lesser priority to reforms was initially overlooked by cheering liberals; they forgot how easily the reform part of the package could be abandoned ... Reform was the bait – what Kennedy wanted was the tax cut.” (The Free Enterprisers: Kennedy, Johnson and the Business Establishment, by Hobart Rowan, p.233.)

Chief Keynesian Walter Heller was not so glum. He told the Societé d’Economie Politique in Paris, November 7, 1963:

”Traditionally, the Democratic Party has placed great stress on tax measures to benefit consumers. But the force of circumstance has raised investment in productive equipment to a higher and higher priority ... Such measures would have been considered unnecessary, perhaps even ‘un-Democratic,’ ten or fifteen years ago.”

During each of the three recessions since 1950, unemployment rose sharply and then returned to increasingly higher plateaus of unemployment after the downturn: to about 3 per cent in 1952-53; 4 per cent in 1955-57; and 5.5 per cent in 1959-60. There had been a total of 5 million unemployed at the bottom of the 1957-58 recession; 14 million were unemployed part time. Kennedy promised to break through the 5 per cent “unemployment barrier” and finally in 1966, the fifth year of expansion, unemployment dropped below the 4 per cent level where it has remained ever since. Was this the result of sophisticated financial policies?

A certain amount of unemployment, as Marx long ago explained, is a fixed necessity under capitalism and a capitalist economy cannot tolerate full or even near-to-full employment over an extended period of time. Such periods inevitably give rise to price inflation because of the combustible combination of high employment and high capacity utilization: The monopolists, on one side, are in a position to maximize profits because competition is limited. The workers, on the other hand, are in a position to fight for better wages because near-to-full employment gives them leverage against the bosses.

In the first phase of an economic upturn, when wages have been weakened by the previous downturn and workers are anxious to get jobs as they become available, the monopolies increase their rates of exploitation and profits begin to climb. But these types of profits are threatened as soon as workers reach employment levels that enable them to fight back. Finally, as near-capacity production and employment set in, the monopolists are once again able to increase prices: Their competitors are also operating at or near capacity and do not have the “incentive” to undercut price increases; since profits are generally high throughout the economy, there is less attraction for a firm seeking higher profits to enter another industry. This form of profit expansion is inflationary: prices are being raised without any increase in demand.

Workers have to catch up. The inflation cuts into their real wages. But they are now in the best position to win better pay precisely because of the high employment conditions. Apologists for capitalism like to call the result a wage-price spiral but it is quite obviously a price-wage spiral

To a certain extent the higher and higher unemployment levels which occurred in the United States in the fifties were a consequence of the monopoly power of US industry. The monopolists had rebuilt the plant and equipment worn out during the depression and World War II. Their profits were plowed into the expanding European economies abroad and plant and equipment investment began to fall off at home. The combination of recessions, inflation and increased unemployment levels all the more enhanced monopoly superprofits, keeping the rate of real-wage rise in the United States substantially below the rates in most European countries (although, of course, US workers started at much higher wage levels and the wage differential is still great).

Furthermore, this pool of unemployed workers created by the recessions of the fifties was an important source of the expansion of the sixties.

But price inflations have tended to become more and more unacceptable to the imperialists with the intensification of world competition. Since they are engaged in world trade, high prices undercut the capitalists’ ability to sell their goods in foreign markets; at the same time, the high prices of domestic goods allow foreign products to penetrate the domestic market

Furthermore, the “classical” solution to this problem, recession, now carries the overhead expense to the imperialists of allowing their “own” economy to lag behind those of their competitors. In this sense, the postwar US recessions were a luxury American imperialism could indulge in because of its dominance in world trade. That is a luxury it can no longer afford. By 1962-63, as I have already noted, the Kennedy administration ruled out the solution of recession.

But text-book Keynesianism requires periods of cyclical unemployment to counteract periods of cyclical price inflation. “Peaks” could be avoided, according to this theory, by federal intervention to cut back on spending and to tighten the money supply. This would increase unemployment and prevent a peak. When unemployment rose back to “ acceptable” levels, the restraint would be relaxed and the economy would be allowed to expand. The men hi the White House in 1962 succeeded in stimulating the economy by increasing federal spending and easing monetary restrictions. But this also ensured a price inflation which began to develop in mid-1965. A comparison of the relevant peak periods is shown below.

The fact that unemployment ultimately fell below the 4 per cent level did not result from the policies of stimulating the economy followed by the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. It was caused by the war in Vietnam. Without that war, the capital spending boom of 1964-65 would have peaked out with price inflation and overproduction, inevitably leading to a recession. The economic specialists who engineered that expansion never expected unemployment to fall below 4 per cent or even down to 4 per cent “ It is now clear,” Seymour Harris wrote in 1964, “that the combination of monetary and fiscal policy required to bring unemployment down to 4 per cent by 1964 or 1965 would be very difficult to achieve ... An annual needed rise of GNP (Gross National Product) of $40 or $50 billion would require a cut in taxes plus a rise of federal spending which would not be acceptable to the Congress or their constituents.” (pp. 6-7.) Nevertheless the GNP did rise $52 billion in 1965 and $63 billion in the following year, but this was because of the war.

|

TABLE ONE |

||

|---|---|---|

|

Period |

Per cent |

Percent increase |

|

January 1947-January 1949 |

3.8 |

5.5 |

|

September 1950-November 1953 |

3.2 |

3.2 |

|

May 1955-September 1957 |

4.1 |

2.4 |

|

July 1965-December 1967 |

3.9 |

2.9 |

As to the fundamental problem, Ackley, Duesenberry and Okun admitted in their 1968 Annual Report. “Neither the United States nor any other major industrial country has fully succeeded in combining price stability with high employment.”

It was only belatedly that the monopolistic giants of US industry woke up to the impending end of their epoch of unchallengeable supremacy in world trade. As late as 1963, some on Wall Street could joke about the mountain of cash profits that was piling up without productive outlets. “The Detroit gag about General Motors,” Hobart Rowan writes, “which in mid-1963 had 2.3 billion in cash and securities (more than the assessed property valuations in 18 of the 50 states) is that GM is saving its cash in order to buy up the Federal Government.” (p.48) When Kennedy rolled back a steel price increase in 1962 some investors ultimately panicked, leading to a sharp dip on the stock exchange.

Plant and equipment investment in US manufacturing industries rose $1 billion in 1962, $1 billion in 1963, $2.9 billion in 1964 and $3.9 biUion in 1965. At the beginning of 1964, about one-fourth of manufacturing equipment in use was less than 3 years old; by the end of 1966 this had grown to one-third. Comparing the five-year

periods of 1955-60 and 1960-65: in the first period, manufacturing plant and equipment investment rose from $11.4 billion to $14.5 billion, or 26 per cent; in the second period, which began with a decline of investment to $13.7 billion, investment rose by 1965 to $22.5 billion, or 64 per cent

The increases in real GNP for the United States and its main competitors over the same two five-year periods is shown in Table Two below.

|

TABLE TWO |

||

|

|

1955-60 |

1960-65 |

|

United States |

2.2 |

4.7 |

|

Germany |

6.3 |

4.8 |

|

France |

4.6 |

5.1 |

|

United Kingdom |

2.8 |

3.3 |

|

Japan |

9.7 |

9.7 |

|

Italy |

5.5 |

5.1 |

The cooling off of the boom produced by the rebuilding of Europe and Japan had pluses as well as minuses for US monopolists. It narrowed the wage differential between US and foreign labor. The big increases in the European standard of living inevitably meant that the rates of exploitation tended to decline. In the first part of the postwar period there were also the population fluxes, from the “underdeveloped” south (Portugal, Spain, Southern Italy, Greece, Turkey) to the advanced north (France, Germany, Northern Italy, UK). And these exerted additional downward pressures on wages. But stabilization brought with it an end to these fluxes and even a certain “de-migration.”

”The data do make clear,” the Council of Economic Advisers stressed in its 1968 Annual Report, “that during much of the decade of the 1950s, US costs and prices rose faster than those of our major competitors. Within recent years, however, the situation with respect to costs was reversed.

”In manufacturing, US unit labor costs (the largest element in total costs) declined between 1961 and 1965, while costs in other countries except Canada increased substantially [Table Three] ... Many of our trading partners are facing fundamental structural changes in their economies. The labor supply situation that permitted the period of extremely rapid growth in Europe had altered fundamentally. The growth of the European labor force in the next decade will be much smaller than in the recent past, and less scope remains for shifting European labor out of less efficient pursuits, such as agriculture, or out of unemployment into industrial activity. This will mean greater European demands for labor-saving machinery, in which US producers hold a marked competitive edge; it may also increase pressures in the European labor market and strengthen the bargaining power of European workers [this concern of Washington’s economists for European labor is touching – D.R.]. Finally, with the elimination of all tarriff barriers this year, internal EEC trade will no longer receive the further benefit of periodic duty reductions. Therefore, with proper economic management at home, the United States has an excellent opportunity to strengthen its trade surplus over time.” (pp.177-8)

|

TABLE THREE |

||||||||

|

|

1962** |

1963 |

|

1964 |

|

1965 |

|

1966 |

|

United States |

99 |

98 |

98 |

97 |

99 |

|||

|

Canada |

99 |

98 |

97 |

99 |

103 |

|||

|

France |

107 |

112 |

117 |

119 |

116 |

|||

|

Germany |

107 |

110 |

110 |

117 |

123 |

|||

|

Italy |

107 |

118 |

123 |

120 |

118 |

|||

|

Japan |

109 |

114 |

111 |

118 |

l15 |

|||

|

UK |

103 |

102 |

103 |

108 |

113 |

|||

|

* Ratio of wages, salaries and supplements to production. |

||||||||

But US imperialism has been largely deprived of the benefits of this situation by price inflation. The wage differentials between US and foreign labor have not been overcome. They remain the most pressing problem to US monopolists in world competition.

The inflationary character of a period combining near-to-full employment and near-capacity utilization has already been described. The years 1965 and 1966 showed that the US was no exception to the rule. As of mid-1965 unemployment was down to 4.5 per cent At the end of 1966, manufacturing industries were operating at an estimated 89 per cent of capacity, a level exceeded only in 1951 and 1953 in the postwar period. The big upsurge in war spending, beginning in mid-1965, assured that inflation would accelerate: not only because of the directly inflationary effects of government expenditures on war goods, but also because the war served to prevent a recession and capital investment surged ahead when the economy was already “overstrained,” in other words, when unemployment was already at a low level.

Consumer prices, which had increased at the rate of about 1 per cent per year since 1958, climbed 2 per cent between December 1964 and December 1965 and 3.3 per cent between December 1965 and December 1966. Housewives picketed supermarkets across the nation and workers fought for higher wages. Between November 1965 and September 1966, they won an average hourly earning increase of 3.4 per cent.

But even these wage increases were too much for the imperialists. President Johnson spluttered about a “wage-price guideline” of 3.2 per cent, which was actually lower than the 1965-66 increase in consumer prices already mentioned. The Council of Economic Advisers complained,

”Workers in low-paid occupations could not be retained without substantial upward adjustments of wage scales. Moreover, reduced unemployment strengthened the bargaining position of unions and weakened that of employers . . . Prices of services of all kinds continued to rise, and at an accelerated rate, as wages in many service occupations were increased substantially . . . Experience shows that rapidly rising prices can quickly erode a country’s competitive position in international markets.” (1967 Annual Report, p.73.)

The capitalists’ high-employment problem was exacerbated by the war in Vietnam. Just when they needed more unemployment to lower wages, they decided to throw tens of thousands of young men into the trenches of Vietnam which stimulated a war industry employing tens of thousands of others at home. Predicting (and fervently hoping) that the armed forces level in Vietnam would reach 600,000 by the end of 1967, the US News and World Report agonized about the resulting effect on the labor force:

“Labor shortages – skilled and even unskilled – will grow more severe. Unemployment, now at 3.9 per cent of the work force, will slip to 3.5 per cent by next spring, and fall to a mere [sic] 3.1 percent by year-end ... A manpower squeeze is the biggest single economic worry for the months ahead ... Says one planner: ‘The major impact of a troop build-up will be to aggravate shortages of labor. That will mean even bigger wage demands – and settlements – than would otherwise be the case. So we can expect more wage-price push, more inflation.’” (September 12, 1966.)

As early as December 1965 the Federal Reserve Board had anticipated the “crisis” of a tight labor market and began raising its discount rate in order to tighten the money supply. The wisdom here was straightforward enough: Interest rates would be driven upwards enough to cause a transfer of labor from interest-sensitive sectors of production (like housing) toward the war industry without necessitating wage increases in the process. A little later President Johnson suspended the 7 per cent tax credit to corporations. As production began to decline in the fall of 1966, Business Week assured its readers that,

“The experts see the declining indicators only as a sign that the monetary policy is being used in a wholly new way; to make the civilian economy give up its command over scarce resources, thereby freeing them for use in Vietnam.” (October 8.)

But this plan was already out of hand by winter. The main factors which would produce a recession had developed: housing construction fell off by one-third; layoffs were beginning in auto; inventories pushed far ahead of sales; there was a slight decline in capital investment Alarmed at this manifestation of a recessionary downturn, the Federal Reserve Board went into reverse. Credit restrictions were loosened in the closing months of 1966 thereby easing the money supply. The tax credit to business was restored. And when the inventory liquidation had ended by mid-1967, the economy, spurred on by war, resumed its previous inflationary pace.

The Council of Economic Advisers commented on this experience and also made a cogent observation:

“While the avoidance of recession was a major favorable development, it cannot be read as an indication that the business cycle is dead. On the contrary, the sharp inventory swing showed the continued vulnerability of the economy to cyclical forces.” (Annual Report, 1968 p.43)

Even more significant, however, was another comment elsewhere in the report: “The unsatisfactory price performance of 1966 continued through 1967; consumer prices again rose nearly 3 per cent.” (p.39) In other words, the fiscal and monetary policies had failed to do the most important thing, so far as Washington was concerned. They nearly precipitated a recession; but they failed to stem the inflation. The US, at the end of a year of international monetary crisis, was in a worse position than before.

The inflation allowed foreign goods to enter the US market, possibly even faster than the economists of the Kennedy administration had feared. The US trade surplus rose from 1963’s $5.3 billion one more year to $7 billion in 1964 but then began to slide. The trade surplus was $5.3 billion in 1965; $3.8 billion in 1966 and 1967; and $1 billion in 1968.

Imports of certain manufactured goods soared – particularly steel, industrial machinery, autos, electrical equipment and textiles. Imports of TV sets went up 60 per cent in 1968 alone. Steel imports are perhaps the most striking, rising from less than 3 per cent of domestic consumption before 1964 to 15 per cent in 1968. The impact of these imports on the US steel industry’s monopoly pricing is significant. Steel prices increased 35 per cent between 1953 and 1961 but only 7.5 per cent between 1961 and 1968!

The intensification of world competition in auto has been more noticeable to Americans, since much of the battle in world auto seems to take place in the commericals on American TV. One million foreign cars flooded into the US last year, well over half of them West German Volkswagens. Henry Ford II recently told Der Spiegel, “Yes, we were not on our toes in the past Yes, the Japanese are more dangerous competitors than Europeans. Yes, they make him ‘furious.’” Ford added,

“I would have gladly bought Volkswagen in 1948, but unfortunately that did not happen. I talked about it with representatives of the British Military Government in Germany at that time, but they said ‘no.’” (Translated in Atlas, June 1969)

The upsurge of imports would have capsized the US balance of payments in 1968 were it not for the sharp rise in interest rates which also took place. These high interest rates coupled with a booming stock market attracted a heavy increase in foreign investment in this country, which jumped from about $3 billion in 1967 to well over $10 billion last year.

Throughout the postwar period, the US ruling class has steadily increased its foreign investments, and this has taken place in three successively larger leaps: first, after the war itself; secondly, beginning in 1955; and thirdly, beginning in the early sixties: Total direct investment abroad (that is, investment where the US stockholder has controlling interest or at least 10 per cent of the outstanding stock) stood at $11.8 billion in 1950; $19.3 billion in 1955; $33 billion in 1960; and $66 billion in 1968. The total value of all US assets and investments abroad today stands close to $150 billion.

These investments have been directed more and more toward other advanced capitalist nations. Harry Magdoff calculated the shifting composition of US investments in The Age of Imperialism (Monthly Review, June 1968, p.43): In 1950, US direct foreign investment in manufacturing stood at $3.8 billion, with 15.1 per cent of this in the three largest Latin American nations, Mexico, Argentina and Brazil, and 24 per cent of it in Europe By 1966 the total direct investment in manufacturing had grown to $22 billion with 11.4 per cent in Mexico, Argentina and Brazil and 40.3 per cent of it in Europe.

It is evident that whatever the vicissitudes of the US economy at the time, the monopolists have pumped more and more capital abroad. Striking cases of this occurred in the sixties when the US was already experiencing large balance of payments deficits and supposedly marshalling all of its energy into halting the outflow of dollars. But 1964 and 1967 saw record-breaking totals of foreign investment: $11 billion in 1964 and $10.4 billion in 1967. The Council of Economic Advisers found the jump in 1964 “difficult to explain” in its 1967 Annual Report.

“Earnings on investments in Europe have fallen since 1962. Between 1955 and 1962, rates of return on investments of US manufacturing affiliates in Europe, at 14 to 19 per cent, were significantly higher each year than the 10 to 15 per cent earned by US manufacturers at home. However, since 1962, earnings on direct investments in Europe have varied between 12 and 14 percent, about the same as, or – in 1965 – even below, those in the United States.” (pp. 83-4)

The Council of Economic Advisers appears to forget that the interests of the capitalist rulers are not uniform and that some financiers may have been even more far-sighted than the Keynesian experts. Faced with continued inflation, these investors saw the potential profitability of manufacturing goods abroad and selling them in the United States.

In fact, the world network of foreign subsidiaries of US corporations produces many more goods for sale (and “export”) than the United States directly exports on the world market. The total output of US foreign subsidiaries has been estimated at $200 billion in 1968 compared to US exports of only $33 billion (Steel Labor, July 1969). Many of these “foreign” goods are sold in the United States, so that the monopolists involved have doubly upset the balance of payments: in the first place by pouring dollars into foreign investments and in the second place by selling the United States “foreign” goods. And this is not to speak of their consequent interest in seeing that the United States has more and bigger inflation.

The CEA admonishes such malpractices: “Despite the advantages of US foreign investment both to the recipient countries and to the United States, it can – like every good thing – be overdone ... In some cases, US plants abroad supply markets that would otherwise have been supplied from the United States, with a consequent adverse direct effect on US exports.” (1967 Annual Report, p. 189)

The CEA appears to have dropped its veil of impartiality on matters concerning competing interests of US corporations. It favors “domestic” US interests over “foreign.” But this is utterly factitious. The economists neglect to inform us who these double-dealing monopolists are, who own the US subsidiaries abroad.

“In the three biggest European markets,” The Economist gave as an answer to this question, “West Germany, Britain and France, 40 per cent of American direct investment is accounted for by three firms – Esso, General Motors and Ford. In all Western Europe, twenty American firms account for two-thirds of American investment.” (December 17, 1966.)

The president’s economic advisers, of course, are well aware of these figures. Their remarks, couched in the polite terminology of international finance, were simply meant as a reminder to the capitalist rulers of the short-term dangers involved in their expansionist policies. Washington found it necessary to put temporary restraints on foreign investment in 1965 and 1968 with little objection from the business world. The capital necessary to finance continued expansion of foreign interests was raised abroad instead.

Along with Johnson’s policies on Vietnam, the Nixon administration inherited and is continuing the Johnson administration’s economic policies. These are policies of restraint, aimed at slowing inflationary price rises which have reached unsustainable levels, not only so far as world trade is concerned, but for the expansion of the domestic economy as well. The experts hope to duplicate the “mini-recession” of 1966-67 – only with better results. I have pointed out that whereas Washington succeeded in slowing down the economy then, it did not succeed in its main objective, slowing inflation. Prices rose through the slowdown and then rose even faster in 1968 and this year.

In essence, the imperialists would like to have recessionary effects without a recession. They have tried to rule out drastic fiscal and monetary restraint because,

“the cost would be intolerable – unemployment would rise substantially, and the United States could easily experience its first recession in nearly a decade. As the over-all unemployment rate rose, the rates for the disadvantaged – including non-whites and teenagers – would rise even more rapidly. With heavy unemployment among even experienced workers, it would be extremely difficult to sustain recent initiatives to provide training and jobs for the unskilled and the disadvantaged. The danger of serious social unrest would be greatly increased. Moreover, the entire economy would suffer a huge loss of output, at a time when full production of goods and services is urgently needed to fulfill national goals.” (1969 Annual Report, p.53)

There can be no question of their “sincerity” in these regards. It is another question whether they can pull it off. Government and industry have pushed the economy to the point where a slowdown in inevitable. The decisive question is how successful the government will be in cutting it off once it starts – whether it can repeat the “solution” of 1967.

The policies of the Federal Reserve Board turned toward tight money in 1967 and they have continued to tighten, squeezing interest rates to an historic high. In the early part of 1968, Congress passed the income-tax surcharge that the Council of Economic Advisers had pressed for since 1967. Nearly every economist and almost the entire financial press expected a slowdown to begin over a year ago. Apparently the opposite happened. What they underestimated was the force of the drive for world technological superiority of US industry.

Each raising of interest rates has been followed by an expansion of capital outlays and this all the more drives interest rates upward as money comes in shorter and shorter supply. US monopolies have responded to what they believe to be a guaranteed short-term inflation with policies that actually guarantee such an inflation. Believing that costs will rise in the near future, they have pumped spending to the upper limits in order to save on future costs to keep up with domestic and international competition. The mo re powerful are leading the way.

An example of this was cited in the Wall Street Journal, May 26:

“Times are good here in this rolling township of 2,000 people [Lordstown, Ohio]. In fact, some say times are too good. Unskilled laborers here can earn as much as $400 a week, and skilled tradesmen can get $600 or more as they put in long hours to hurry along a $75 million plant being rushed by General Motors Corp ... The GM plant, says an executive at a big Ohio manufacturing company, ‘is breeding discontent through this whole area.’”

In Lorain, Ohio, less that two months later, construction workers won a 49 per cent, 13-month wage increase. The investment-price-wage spiral may yet drive prices and interest rates considerably higher and adds a most explosive unknown to the economic mix.

But the spurt in capital spending itself, like the comparable spurt in 1964-66, will inevitably lead to an overproduction peak and force inventory liquidation. As of this writing warnings have already been sounded about “too much inventory build up.” Every time it happens the pundits of the press seem to forget that there is no way of preventing it! To avoid inventory build up would require that certain industrialists step forward and volunteer to cut back production while their competitors are still’ pressing forward to carve out what remains of the market Before that happens, most capitalists will actually go far into debt to finance inventories in order to keep them abreast of competition. This, incidentally, is one of the reasons why interest rates shoot up at the end of a business cycle.

Furthermore the tight money policies being followed by the Federal Reserve Board will take their toll: housing construction has already begun to fall off and there are suggestions of production cut-backs elsewhere. The Nixon administration is bent on adding to this continuation of the tax surcharge and repeal of the investment tax credit In all, this is powerful – if clumsy – economic restraint To make matters somewhat different from the comparable peaks of 1965 and 1967, military spending is not on an increase but is gradually levelling off and there have already been layoffs in major war plants.

Finally, there is the entirely unknown factor of the interrelation between a slowdown in this country and the rest of the capitalist world. Imperialism counts for its good health on uneven cycles from one nation to the next, upturns in this economy that will soften the impact of downturns in the next But the law of uneven and combined development applies to world investment patterns as to all other social patterns. In order to overcome the contradictions of one national economy, the imperialists must ultimately internationalize these contradictions. The economies of the entire capitalist world are moving toward a generalized recession recession from world overproduction – for the first time in postwar history. It cannot be ruled out that the coming American slowdown will be the spark that ignites this fuse.

* * *

The attempt of monopoly to solve its own contradictions by internationalizing them is not new, but the essence of imperialism as Lenin defined it in 1917. And to this extent the parochial nationalism of the Keynesians rules out success from the start Imperialism is not always so patriotic. It recognizes that world markets are the best buffer against national economic “upsets” and it attempts to protect itself against the fluctuations of’its “own” market But it is also super-patriotic in the last analysis. For the base of its material power resides in its political control of the nation-state.

Not only is the sum total of the imperialists’ domestic investment likely to be larger than their total foreign holdings. More important, their government, their army, their police, are based “at home.” This state apparatus is crucial in protecting world monopoly investment; next to it all fluctuations of the business cycle are secondary.

In the case of the United States, this state apparatus is a world police force; its domain of patrol is the world network of US investment; its main weapon in the economic arena is the dollar. US imperialism did not enter the decade of the sixties with the thought in mind of easing outoffirstplace in order to assure a more rationally integrated world economic system. On the contrary, it entered it with the perspective of continuing the epoch of “Pax Americana” forever. All economic policies were bent in that direction alone.

Seymour Harris recalls a revealing episode of the Economics of the Kennedy Years. Many financial advisers, apparently including Harris himself, tried to persuade Kennedy to devalue the dollar as the quickest and easiest solution to the US balance of payments deficit But Kennedy preferred “to improve our competitive position by containing wage and price inflation, by raising productivity, by stimulating the marketing of goods and services, by encouraging foreign tourists, by transferring some of the burden of military expenditure and foreign aid to its allies, by discouraging excessive exports of capital and by increased procurement for economic and military aid abroad. This is the approach favored in Washington, although it is the hard way out” Harris wrote in 1964 (p.35).

The correct word for it is not “hard,” but “impossible.” Seven years later the international monetary situation and the position of the dollar is much shakier, US industry has continually slipped further behind in world trade – foreign tourists didn’t even come to the New York World’s Fair, they went to Expo along with many Americans instead! – exports of capital have nearly doubled, and the United States has avoided recessions twice – in 1965 and 1967 – only because of the murderous slaughter in Vietnam. US imperialism did not shift the burden of this military expenditure to its “allies”; it taxed the American people to the gills – and is still taxing them – to carry on the war and is undergoing an inflation as a result the full consequences of which cannot yet be estimated. That is the record so far. But in addition to an inflation which is daily eating further into consumer purchasing power there is going to be an economic slowdown and there looms the danger of this turning into recession. It is yet necessary to experience these legacies of the sixties in order to draw the final balance sheet

ISR Index | Main Newspaper Index

Encyclopedia of Trotskyism | Marxists’ Internet Archive

Last updated on 23 June 2009