Activists demonstrate on the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade in 2012.

Activists demonstrate on the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade in 2012.Date: January 22, 2015

In recognition of the 42nd anniversary of the Roe v. Wade decision, we present this article summarizing the history of U.S. policy around reproductive rights from 1973 to present, with a special focus on new developments from the past couple of years.

The 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade that overturned laws outlawing abortion came as a result of a women’s movement that demonstrated, testified, and in some cases organized an underground railroad to enable women to obtain the abortions they needed. It was also a movement that raised demands for ending all restrictions on abortion (which unfortunately is not what the decision laid out). The movement also demanded programs for women’s health, sex education, access to birth control methods, and the right to have, and raise, children.

Activists demonstrate on the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade in 2012.

Activists demonstrate on the 40th anniversary of Roe v. Wade in 2012.

While current U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg has remarked that the Roe v. Wade decision was too sweeping, women who were involved at that time welcomed what we saw as an important but flawed decision. We saw decriminalization of abortion as a step along the way to women’s liberation. We also realized that the right wing was not going to give up their demand that women don’t need to be able to control our bodies (although they wouldn’t frame it that starkly). In fact, Roe v. Wade was never fully implemented. Most hospitals refused to perform the procedure and medical schools were not interested in educating their personnel on the issue. Meanwhile, clinics—many of them founded by women active in the movement—were targeted politically.

Generally speaking, the right wing did not attack women directly for wanting an abortion but targeted health care providers as greedy for clients. This included physical attacks on clinics, but also the harassment and murder of several physicians. Their tactic was to talk about “the abortion industry” and to set up nearby clinics where they offered free pregnancy tests and then find women who were seeking an abortion and try to counsel them out of one.

On the legal front, the right’s strategy has to been to find the areas where Americans are conflicted over sexuality or family relations. They attempted to pass both spousal and parental consent, but only the latter proved possible. They did succeed in getting Congress to pass the Hyde Amendment, a restriction first passed in 1977 and renewed each year as part of the budget. The amendment prohibits funding for abortions under Medicaid except in cases of rape, incest or to save the woman’s life. Over the years it has been expanded to limit federal funds for abortion for federal employees and women serviced by the Indian Health Service. Using the debate around supposedly “irresponsible” sexuality of people in poverty, the right was able to use this wedge in order to attack the poorest and vulnerable women in society first.

The right also targeted late-term abortions as particularly horrendous and were successful in passing a federal bill that outlawed a medical procedure. (The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that this law was constitutional in its Gonzales v. Carhartt decision.) In fact, fewer than one percent of all abortions are performed after 20 weeks.

By 1992 the U.S. Supreme Court, in its Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision, ruled that where restrictions did not place an “undue burden” on a woman they were constitutional. This opened a can of worms that rightwing legislators have used to require 24-hour waiting periods, mandate costly and unnecessary procedures including ultrasound, usually with the doctor reading a script—often of contested “facts”—about fetal development even when the woman declined to hear. By mandating ultrasounds for all abortions, legislators took an important medical procedure and distorted it by demanding it even when medically unnecessary, requiring that the physician performing the abortion be the person performing the ultrasound, and insisting that the woman listen. This denies woman’s right to make informed decisions and conveniently drives up the cost of the abortion.

After the passage of so many restrictions on abortion procedures and increasing attacks on contraceptive information, the right seems to feel wind in its sails and various spokespeople—including the former Lieut. Governor of Texas, David Dewhurst, an oil and gas businessman—have called for the overturning of Roe v. Wade. The House of Representatives plans to vote on the 20-week abortion ban on the 2015 anniversary of Roe v. Wade. This ban is similar to one passed in Arizona that a federal appeals court called unconstitutional and was refused review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) promised coverage to the millions who have no medical insurance but none of the 10 essential benefits outlined for women’s health cover abortion. The provisions of the Hyde Amendment continue to reign. The ACA does mandate contraceptive coverage for both Medicare coverage and insurance providers through the exchanges that have been set up.

Even though the Obama administration exempted religious institutions from contraceptive coverage for their employees, the U.S. Supreme Court has broadened that ruling in its Burwell v. Hobby Lobby decision. Under this ruling, family-owned corporations are also exempt. The majority ruled that having these corporations (we are not talking about mom-and-pop stores, but mayor employers!) offer insurance policies which covered contraceptives the companies identified as abortifacents (whether true or not) would substantially burden their religious freedom. Supreme Court Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., writing the majority opinion, claimed the ruling was limited in its scope and stated that if the government had a compelling interest in making sure women have access to contraception it could find ways to provide the coverage. owever the spade of challenges to ACA contracptive coverage grows.

Many observers speculate that some set of restrictions will be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court sometime within the next couple of years. Yet more than one million women living in the United States obtain abortions each year; over a woman’s lifetime, one-third secure an abortion. The reality is that the wide range of reproductive justice issues needs to be enlarged, not contracted.

In 2014, 15 states passed 26 laws restricting abortions; the previous year 22 states had passed 70 restrictions. Since 2010 a total of 231 restrictions have been passed. These have been in four areas:

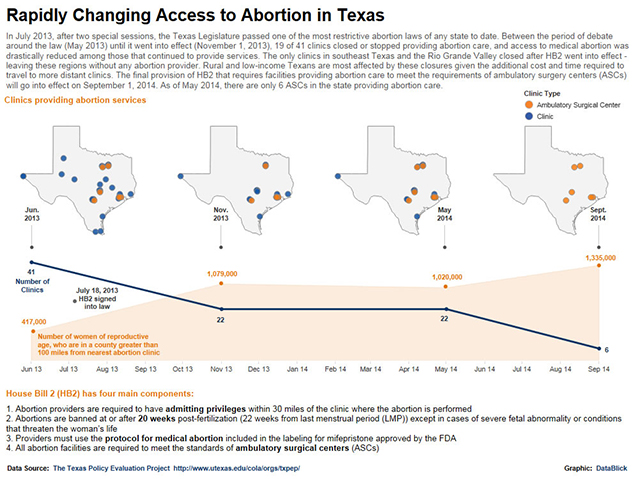

A critical bill passed by the Texas legislature in the summer of 2013 brings together four elements in the latest rightwing line of attack:

Click here for larger image.

Click here for larger image.

The first three parts of the law went into effect in November 2013, but Federal Judge Lee Yeakel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held the first section unconstitutional. Of the 42 Texas clinics where abortions were performed in 2012, 17 remain open, although they are in fewer areas of the state. (See this map.) The fourth provision was to become effective on September 1, 2014—resulting in 10 more clinics being forced to close—but Judge Yeakel ruled that provision unconstitutional as well.

In January 2015 the Fifth Circuit conducted hearings on the 2013 law. The state argued that its legislators have the right to decide issues regarding the health of its people and that there is no undue burden on women seeking abortion because women would have to drive no more than 150 miles to a clinic. Given the 24-hour waiting period, the woman might have to take several days off work. If early in her pregnancy, a woman might want to have a medical abortion, but would be forced under the 2013 provision to come to the clinic on four different dates. (Texas already outlawed telemedicine for abortion.)

Needless to say, Texas does not provide for publicly funded abortions under most circumstances. In 2011 it limited public funding for birth control and specifically targeted Planned Parenthood clinics for defunding. Women who are poor and have no health insurance are much more likely to become pregnant and will have a greater need to seek an abortion, not only in Texas but nationally.

Dianne Feeley has been active in the reproductive rights movement since the 1960s and was active in organizing the first demonstrations against the Hyde Amendment. She is a member of Solidarity and an editor of Against the Current. She would like to thank Zoe Holden for valuable contributions to this article.