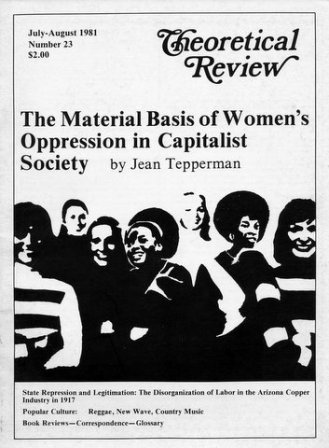

First Published: Theoretical Review No. 23, July-August 1981

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Dear TR:

Thanks very much for sending along the issue of Theoretical Review with your Springsteen piece. It is probably the only lucid piece of marxist rock criticism I have read. (Unless Simon Frith is a marxist, which I sort of doubt.) It is also one of the most intriguing reviews of The River and Springsteen’s music that I’ve come across lately. Let me know if you’d like me to forward a copy to Bruce; I think he’d very much like to read it.

Although, on the other hand, I’m not sure how much he would understand it. One thing that’s necessary to remember about his work and its progressive tendencies is that he makes it up as he goes along: Springsteen has only a high school education, and not a terribly good one of those; and his encounters with any serious discussions of issues and values outside the popular mainstream as limited. I, too, cringe at some of Springsteen’s sexual stereotyping, the most egregious example of which actually comes in the live show, when he describes Clarence Clemons as “able to leap tall women at a single bound.” But in a very real sense, he simply doesn’t know any better, and that’s one reason I think that he ought to see your piece. (He took heat from all sides for the female pronouns on The River, and I’m curious to see what the reaction in his new batch of songs will be. Not too much, I fear, since he probably sees such pronouns–not totally incorrectly–as part of rock’s idiomatic expression; this is possibly one reason why the Clemons line strikes me as more gratuitous than any of the rest.)

I do think that you misread one aspect of The River; as I thought he’s made clear in the Musician interview, Bruce is not always writing from his own perspective on that record. “Jackson Cage,” particularly the lines from it that you have cited, has very little to do with the way that he sees the world, and a great deal to do with the way that he sees others seeing it. (The lines that do reflect his beliefs are near the end: “Are you tough enough to play/The game they play/Or will you just do your time/ And fade away...”) While I’ve admittedly been shocked at Bruce’s utter misreading of capitalism–he seems to think that it’s exactly the opposite of its true nature–it seems to me that The River represents a strong step toward a much more politically involved and progressive performance style. He will never be as overtly political as Gang of Four, for a variety of reasons, having to do with his own instincts for glamour and show biz razzle dazzle and his instinctive distrust of highbrow ideas, but I think that you will be pleasantly surprised by what he does next.

I base this to a great extent on what Springsteen did on his European tour (just now being completed). It was a strange experience to see him performing in Paris, in a hall owned by the CP, singing “This Land Is Your Land” with a new verse that incorporated into Woody Guthrie’s vision, the streets of Brixton. And to hear him pose the song as a question, rather than the usual easy answer. I know also that in England, the single thing Bruce was most curious about was the Trade Union Council’s (TUC) Unemployment March. Lastly, there is the set of new lyrics he wrote for the Elvis song, “Follow That Dream.” While they are still imbued with a good deal of romanticism, I think that in many ways, the verse I’ll quote captures both the despair one can’t avoid feeling in the face of the current economic and political climate and the hope you’re looking for:

Now every man has the right to live

The right to a chance to give what he has to give

The right to fight for the things he believes

For the things that come to him in dreams

I walk in dreams, I live in dreams

Given the way that he sings it, there’s little doubt that the “I” is meant to be universal–that is, that the last line is as inclusive as the first. (On the subject of Elvis songs, it might interest you to know that the lines you quote from “Badlands” on page 26 are lifted wholesale (except the last one) from Presley’s “King of the Whole Wide World.”)

Best,

Dave Marsh

Dave Marsh is a contributing editor of Rolling Stone magazine and is the author of Bruce Springsteen’s biography– Born to Run: The Bruce Springsteen Story. He also writes for the magazine Musician: Player & Listener.