First Published: Forward, No. 4, January 1985.

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

The twists and turns of events in China are often bewildering. As one of many progressives in the U.S. who have been following China with a sympathetic eye over the last decade, I have been perplexed many times. Yet, past experience has taught me that being “bewildered” is more often than not a result of imposing my own assumptions, expectations and prejudices in interpreting Chinese affairs, looking at policies in isolation from the overall context, and jumping to conclusions based on subjective or idealistic views of what I think socialism ought to look like.

The series of economic and administrative reforms instituted in China over the past several years is clearly a case where interpretations based on simplistic formulas or idealistic expectations about socialism are bound to lead to confusion. Already, “China watchers” in this country are talking about the “restoration of capitalism” in China. The rural responsibility system, the increased autonomy of large industrial enterprises, the use of “free market” mechanisms to regulate supply and demand, and the stress on developing an active commodity economy are taken as signs that China has now abandoned the “socialist road.”

To say that such conclusions are premature would be too generous. I don’t think they have any real basis in fact. I can’t help but feel that such views stem from wishful thinking on the one hand and the disillusionment of idealistic expectations on the other. Such perspectives are often the product of defining socialism in terms of some universal formula or a rigid set of political, economic and social institutions. Accordingly, any deviation from this formula or institutional framework is seen as a departure from the “socialist road.”

The construction of socialism in an advanced industrial country will take a very different form as compared to socialist construction in a developing country such as China. Differences in social, political, economic and historical conditions will result in very different manifestations of socialism. Socialist institutions and policies cannot be expected to take the same shape in all countries.

This is not to say, however, that socialism can’t be defined or that there are no features and characteristics of socialist societies in general. First and foremost a socialist system is one in which the working class and its allies hold political power. This political power is used to implement policies and build institutions that defend their class interest. Second, a socialist system is one in which the exploitation of one class of people by another is abolished. The eradication of class exploitation distinguishes socialism from all systems that have historically come before. Third, socialism is characterized by the public ownership of the main means of production in society. The factories, the power plants, the mines and other production facilities are owned publicly or collectively by those who work them.

China’s responsibility system does not lie outside of this general concept of socialism. This is not to say that I would defend China’s current reform movement as being the final solution to the problem of socialist modernization. Such a conclusion would be premature.

Before going into some of the reasons for making the above assertion, it would be useful to look at the background and context of the reform movement in China today.

Since 1949, China has been trying to tackle some of the basic problems it confronts as a poor, third world country. Like most third world countries, the majority of China’s population is in the agricultural sector (80%), and the greater part of its social wealth comes from agricultural production. Beginning from this base, China is striving to become an advanced, industrial country by the beginning of the next century.

The dimensions of this goal are truly staggering. China is a country of one billion people. In absolute terms, its industrial base is already very powerful: China is a leading world producer of coal and steel. In relative terms, in terms of production per capita, however, China is unquestionably poor. Thus, the China that can launch satellites is still a developing, agrarian country.

To meet the ambitious goals set for the end of this century, China must accelerate the expansion of its social wealth in order to have the resources necessary for industrialization. As an agrarian country, this expansion of social wealth must take place primarily in its agricultural sector. Per capita agricultural output must be dramatically increased. So long as agricultural producers consume a large proportion of what they produce, the funds needed for development can only accumulate very slowly.

Per capita agricultural output can be increased in a variety of ways. Mechanization, where conditions permit, is one technique. The use of scientific farming to increase yields is another. The reorganization of agricultural production for greater efficiency is another possibility. Restricting consumption can also produce the same economic effect with respect to industrialization as increasing output. The stabilization of population growth must also accompany an effort to increase per capita output.

All developing third world countries, socialist or capitalist, must accomplish this task some way. Countries with special natural resources such as oil can minimize or even eliminate dependence on the agricultural sector. Foreign loans and international trade can help ease the burden shouldered by the agricultural sector. The balance of light and heavy industry implemented by the country’s industrialization policy can also have a tremendous impact on the pressures imposed on agriculture.

Although all developing countries face the same basic problem, there is a sharp distinction between socialist and capitalist solutions. Capitalist methods intensify the difficulties faced by agricultural producers. Peasant farmers are plundered through the expropriation of land, landlordism, heavy taxation or usury. In many situations, capitalist methods lead to cash-crop economies, which cannot adequately feed the population. In most cases, these methods lead to an underdevelopment of the agricultural sector. A developing socialist society like China, under the alliance of the proletariat and peasantry, cannot tolerate this type of exploitation of agricultural producers; yet, the resources necessary for modernization must somehow be extracted from agriculture. To accomplish this task without ’ betraying the worker-peasant alliance is the single greatest challenge facing socialist agricultural policy.

The first major step in the formulation of a comprehensive agricultural policy in socialist China was land reform beginning in 1950. Land reform eliminated landlordism and tenancy and created individual agricultural producers. Landlord holdings were confiscated and divided among the peasant households. All peasants received some land. This ended the main form of exploitative relationships in the countryside. In this context, land reform in China must be viewed as a consistently socialist policy.

The second major step was collectivization. The process of encouraging individual peasant households to share resources and tools and to cooperate in cultivation began soon after land reform. The collectivization movement began in 1955 and culminated in the establishment of people’s communes in 1958. The basic and original purpose of collectivization was to expand agricultural production and to ease some of the hardships faced by the agricultural sector in the process of rapid industrialization. Efficiencies of scale (larger plots of land), efficiencies resulting from cooperative work, the opening of new land through reclamation projects and the creation of large tracts of land suitable for the application of machinery were some of the major expectations. In many ways, collectivization was also a matter of survival.

The international blockade against China at the time imposed severe hardships on the country as a whole; without an effective way to share these hardships, many peasant households would have simply “gone under.”

In many cases, the expectations held for collectivization were met. Production was increased; new lands were opened; production became more rational and efficient. In other cases, the effort was less than successful. According to current Chinese assessments of the late 1950s and early 1960s, however, the process of evaluating the success of collectivization vis-a-vis these expectations was distorted by an emerging political trend that saw collectivization as a social revolution divorced from its economic consequences. People’s communes came to be seen as an expression of the socialist “ideal” in the countryside equating socialism with collectivization.

By the time of the cultural revolution (1966-1976), “the higher the level of collectivization, the better” had become a widespread view. Collectivization versus individual household production was no longer debated within the context of socialist agricultural policy, but became polarized into the arena of “socialist road versus capitalist road.” Collectivization had become a virtue or socialist principle in and of itself, independent of actual economic results and its consequences on the living conditions of the people.

According to current Chinese views, this approach to agricultural policy led to stagnation. While production did rise throughout most of the cultural revolution period, so did population. Overall per capita productivity was low, and there was a significant degree of underemployment, both masked by the system of collective production and income distribution. Furthermore, the differential between rural and urban incomes and living standards was very sharp. A great many rural families were living on annual incomes that were roughly equal to the monthly incomes of urban families. This is precisely the kind of polarization between industrial and agricultural sectors or “town and country” that socialist policy aims at avoiding. These and other assessments led to the formulation of a new set of agricultural policies that today are known as “the responsibility system.”

The responsibility system was designed as a way to break out of the earlier period of stagnation. Like collectivization in its initial stages, the primary goal is to expand per capita agricultural production as rapidly as possible, in a way that is consistent with socialism. This system, as it has evolved over the past five years, has the following features:

1. The individual farming household has replaced the larger collective (usually consisting of several dozen households, formerly called the production team) as the basic economic unit in agriculture. Each household now plans and manages its own production, making decisions about what to grow, how much to grow, how to allocate labor, whether to invest income in machinery and fertilizer or whether to build a house and buy a TV set. Income is dependent on household output, so that the more the household produces, the more income they have at their disposal.

2. Land is allocated to individual households according to a contract system. Farmers contract land from the state for a period of up to 15 years. The amount of land contracted by a household varies, and is an independent economic decision limited mainly by the availability of land in a given area and the capabilities of the household. Some farmers contract large tracts; others contract small ones. The decision is based on what a household thinks it can manage, and how much of the household’s income is dependent on land cultivation. Land ownership, however, remains in the hands of the state and cannot be bought or sold.

3. The contract system also has applications beyond access to land. Rural households can enter into contracts with the state to raise pigs and ducks or manage fish ponds. They can enter into contracts to produce cash crops (such as cooking oil), provide timber, or process agricultural products and other traditional “sidelines.” Households or individuals can submit contracts to provide transportation services, machine repair services, agronomic services and other activities. Offseason cottage industries are also organized under this system. Partnerships among individuals and households are also starting small-scale industrial projects in the countryside. Some of these enterprises hire workers, although this is very limited.

This “responsibility system” places heavy emphasis on individual initiative and individual latitude in economic decision-making. The economic incentives to increase per capita output are high, since income is directly proportional to output. In the past, the income “leveling” effect of collective income distribution was a serious disincentive to increased productivity. Income was not proportional to the amount of work someone did. Under the present system there is also discretion for individuals as to what to do with their income. A farmer may invest in production, or may consume income in the form of TV sets, bicycles, new homes, etc. Under the old collective system, the collective made decisions about how much income would be put back into production and how much could be distributed for discretionary, individual consumption. Today initiative also takes the form of starting new enterprises. New resources are being tapped, unfilled economic niches are being exploited, and underemployment is being reduced through these activities. Such enterprises are already contributing significantly to China’s total industrial output.

This emphasis on the individual producer (that is, the individual farmer or rural household), however, does not eliminate state planning nor does it minimize the active role played by local, regional, and central government bodies. Targets set by these levels of government must still be met and must be carried out within the framework of existing laws and regulations with respect to hiring labor, making use of state property and protecting the environment. The contract system operates as a supplement to state-owned and state-managed industries and does not operate independently of the larger socialist economy. Thus, while it leads to diversification of the economy and introduces a great deal of leeway in local and individual decision-making, it is not a “laissez-faire” system. Greater latitude on localized day-to-day economic decision-making, in fact, is seen as a way to make state planning more effective and responsive to the needs of the people.

The aim of the responsibility system in the countryside is to increase per capita agricultural output. The 7.5% average annual growth rate in agricultural output seen over the last five years is a significant measure of the initial success of this system. The 400 million ton target for grain production by 1985 as set in the current five-year plan does not seem unreasonable, since 380 million tons were produced in 1983.

Rural per capita incomes have risen sharply, and are perhaps an even better reflection of the performance of the responsibility system than gross output figures.[1] Since 1978, annual rural per capita incomes have doubled, to reach 270 RMB in 1983 (one RMB or “yuan” exchanges for somewhat more than .50 U.S. dollars).[2]

The rise in per capita incomes, however, does not show the full impact of the rural responsibility system in the countryside. There are two other particularly significant developments that deserve attention.

First, the rapid expansion of small-scale service and industrial activity in the countryside, stimulated by the responsibility system, has diversified the rural economy. This begins to resolve the problem of underemployment. It also reduces the dependence of rural households on crop cultivation as their major source of income. In fact, Chinese statisticians point out that there is a direct relationship between the prosperity of a household and the diversity of its income sources. The poorer rural households are those that rely entirely on crop cultivation.

The significance of this development, if it can continue to move in this direction, is this: without the full mechanization of agriculture in China (and this seems very far off), the discrepancy between the productivity of agricultural and industrial labor will continue. The countryside will remain poorer, while the industrial cities will enjoy relative prosperity. This isn’t necessarily due to the exploitation of the countryside by the cities (although this happens under capitalist development), but due to the fact that agricultural labor, without major technological advances, does not produce as much value as industrial labor. Countries like Japan, where rice cultivation is minimally mechanized, solve this problem by massive government subsidies to their farmers and/or protectionist barriers coupled with price supports. This is not even a remotely possible solution for China. The diversification of rural incomes and the possibility of engaging in part-time crop cultivation can build rural prosperity without artificially raising grain prices and fueling inflation. Potentially this is a major step towards closing the rural-urban gap.

Second, the rise in rural incomes is taking place at a time when a major emphasis is being placed on the production of consumer goods in the industrial sector. Newly prosperous rural households with virtually complete discretion as to how to dispose of their income, are becoming a major market for China’s growing light industrial sector. The growth of the commodity economy in China means that agricultural surplus can be transferred into industry through the sale of industrial commodities to the rural market, rather than through taxation or the imposed discipline of restricted consumption characteristic of the collective system. This process, at the same time, improves the rural standard of living.

This development, if it can continue, will represent a major breakthrough in the Chinese economy. If industry cannot produce large quantities of consumer goods, rising rural incomes will not have an economically productive outlet. Peasant incomes spent on imported goods or on lavish traditional weddings or funerals, etc., do not build the economy. Where these and similar activities are the only outlets for rural income, consumption must be discouraged, savings encouraged, or both practices enforced by official policy. This is why a major component of the economic reforms being implemented in China today is the adjustment of the balance between heavy and light industry, and why this balance has a big impact on the living standard of agricultural producers.

Like any policy or set of policies, the responsibility system may have very serious negative side effects or shortcomings that may eventually come to challenge the viability of the system. As mentioned earlier, some people think that it represents the emergence of capitalism. I’d like to review some of the weaknesses or alleged weaknesses that have been frequently pointed out by Western observers or by the Chinese themselves during the course of policy debate.

One of the most frequently cited problems attributed to the responsibility system is the link between rural resistance to the population policy (one child per family) and the fact that individual households are now the basic economic unit in the countryside. The resistance is acknowledged by Chinese authorities, and the link seems to be a logical conclusion. Peasant households want more children so that their households can be more productive. Furthermore, children continue to represent the main form of “social security” for old people in the countryside.

Although I think there is a legitimate basis to make this link, there is also a danger of taking it too far. First of all, there is a strong resistance to population policy in the country side that is unrelated to the responsibility system. Feudal thinking is deeply entrenched. Family planning has encountered rural opposition from the start, when it was first pushed in the 1950s. Rather than blame the responsibility system itself, I feel that it would be more accurate to say that certain features of the responsibility system are aggravating an existing problem. Secondly, the diversification of the rural economy and the decreasing dependence of rural households on crop cultivation tend to weaken the link. Families dependent entirely on crop cultivation may want more children so that they can contract more land and increase household income, but with the availability of diversified occupations, there is less of an incentive to do this. As to the argument that the more household members working, the larger the household income, the same can be said of the urban family.

Another major argument that has been raised against the responsibility system is that it is hindering the mechanization of agriculture. Large tracts of land on the north China plain, which are suitable for tractor farming, for example, are being broken up to be cultivated as small strips by individual households. This seems to be a valid objection. However, in looking at this problem of mechanization there are several points to keep in mind:

1) Mechanization does not necessarily mean increased production. Mechanization increases the productivity of agricultural labor, but not necessarily the yield per acre. While the productivity of agricultural labor is higher in the U.S. because of mechanization, the productivity of land in China is higher because of intense cultivation. While it is essential to increase agricultural labor productivity, China cannot afford to do this at the expense of decreased yields per acre. Total agricultural output must continue to increase if China is to meet its overall economic goals. Thus breaking up large tracts at the expense of U.S.-style tractor farming may be a reasonable consideration.

2) Agricultural modernization is much more than a problem of mechanization. Increasing yields through scientific farming (which may or may not involve machinery), diversifying the local economy to decrease rural underemployment and absorb people displaced by mechanization, and increasing agricultural labor productivity are all integral parts of a modernization program. In the long run, methods that will increase the labor productivity of the countryside will be crucial in closing the gap between town and country. Mechanization where conditions are suitable (and such conditions do not exist in many parts of China) is therefore only one tactic to be used in a modernization strategy.

3) The above arguments aside, there are strong indications that mechanization in agriculture is on the rise. Recent statistics show a major spurt in the sale of agricultural machinery in 1981, after a lull in the first two years of the responsibility system. While most sales involved small agricultural machinery, large machinery is also being sold. Some of this machinery is being used to fill agricultural service contracts where individuals or small collectives provide mechanized farming services to household farmers without their own machinery.

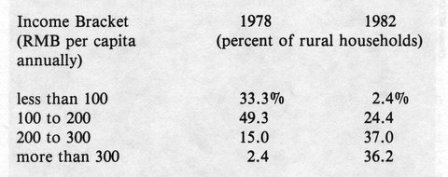

A third objection that has been raised is that the responsibility system is leading to polarization in the countryside between rich and poor households. It is true that a few peasants have become very rich through the “shrewd” utilization of opportunities presented by the system. Examples of farmers buying expensive foreign cars or trucks have received attention in both the Chinese and Western press. It seems to me, though, that these examples are more suitable to Ripley’s Believe It or Not than a representation of real conditions in China. In fact, the statistics for 1982 argue strongly against any real degree of polarization. In 1978, one-third of all rural households were making less than 100 yuan per capita annually. By 1982, this lower income stratum was reduced to 2.4% of all rural households. Let’s look at the following table comparing rural per capita incomes in 1978 and 1982[3]:

The 1982 figures show more incomes weighted towards the upper end when compared with 1978, where income clusters around the 100 to 200 range, weighted towards the lower end. If one is to be concerned about income polarization in Chinese society as a whole, then it should be noted that the highest bracket in 1982, which encompasses less than 7% of all rural households, is still less than the average annual income of an industrial worker on the lower end of the pay scale (There are reports, though, that in some parts of China, rural prosperity is attracting people back from the cities).

Related to this criticism of “polarization” is the concern that the responsibility system has the potential to lead to “land-lordism.” It is argued that public ownership of land does not rule out landlordism growing out of large contracted plots of land, where the individual contractor becomes a “landlord” with respect to poorer households who actually work the land. I would not rule out the possibility that something of this type might occur in a few instances, but it would seem to me that neither the objective conditions nor the framework of the responsibility system would encourage its development into a significant phenomenon. First of all, the kind of polarization needed to create conditions for tenancy does not exist. The number of poor households has gone way down. Secondly, with the right of any household to contract land, why should they become tenants?

The ideological impact of the stress on individual initiative and increasing individual wealth is yet another area of concern with respect to the responsibility system. The emergence of an outlook that takes the form of acquisitive individualism without concern for collective interest or the needs of the society as a whole is certainly a possibility and would cause serious social and political problems in the not-too-distant future. On the other hand, I feel there is a positive aspect to this emphasis on individual interests on an ideological level: by strengthening the concept of individual responsibility and individual interest, the prospects for greater democracy are also enhanced. Unquestioning attitudes towards authority, a “follow the leader” mentality, a resignation to the “powers that be” are aspects of an outlook deeply rooted in Chinese feudalism. This outlook has not been eradicated, despite 35 years of socialism, and has hampered the development of strong democratic institutions and greater pluralism in Chinese political life. If the responsibility system can truly begin to break down this outlook, the negative aspect of fostering individualism may be far outweighed by the positive.

Finally, there has been a tendency to lump many of China’s rural problems together and blame them on the responsibility system. It is important to remember that the responsibility system is being implemented in the countryside at the same time as a whole range of economic, social and political reforms throughout Chinese society is taking place. The re-emergence of many “backward” practices in the countryside during the course of implementing the responsibility system, such as lavish traditional weddings and funerals, for example, stems mainly from the strengthening of constitutional rights and the fact that decades of ideological campaigns have not been successful in rooting out certain old practices.

The responsibility system in China’s countryside is one approach to the problem of socialist modernization. In theory this series of policies and new institutions is no more and no less compatible with a socialist framework than the earlier collective system. Both sets of policies were basically designed to increase agricultural output, modernize agricultural production, generate funds for investment in industrial development and improve living conditions. I think that the reason some people see the responsibility system as a resurgence of capitalism in the countryside is because of certain subjective views they have about collectivization. Collectivization is often associated inseparably with socialism and with an element of moral and ideological superiority. In order to understand the role of the new reforms in China’s socialist development, these views about collectivization must be overcome.

Collectivization is only one of several options open to a socialist country in agricultural policy. Despite its superficial manifestations, collectivized agriculture imposed on pre-modern agricultural conditions is no closer to modernized, socialist agriculture than a system that continues to rely primarily on individual producers. The basic way farming is carried out is the same in both cases. Let me use an analogy to stress this point: if the shoe industry, for example, is at a level of development where it is still carried out by individual cobblers in separate workshops, putting them all into one big room does not necessarily mean that their production has been “socialized.” A modern shoe factory with a division of labor is a qualitatively different phenomenon. There may be very good reasons why cobblers should be encouraged to share materials and tools and to help each other out, just as collectivizing agriculture may have very valid reasons. However, such efforts at collectivization do not in and of themselves lead to modern, let alone socialist, production.

Because of the level of the development of the economic forces, agriculture in China is still based on the work of individual producers, whether or not they are collectivized. This is part of China’s objective reality, and it can only be changed through mechanization, scientific farming and even newer forms of agricultural technology. The past grumbling of Chinese peasants about “everyone eating from the same pot” (referring to the collective system of income distribution, where income was not linked directly to output) has its roots in the individual character of agricultural production, and not in anti-socialist attitudes, backward ideology or human nature. Collectivization does not change this basic method of production; it imposes a strong social discipline on individual producers. A farmer in a collective can always muse, “If only I had my own piece of land. . . .” A factory worker does not have the objective basis to entertain the equivalent kind of thought.

At the same time, I would not agree with the view that the responsibility system is inherently superior to collectivization, as some articles in the Chinese press tend to imply. I think both are legitimate options for socialist agricultural policy, and which is best depends on the concrete conditions to which they are applied.

The most important thing to keep in mind in looking at China, particularly for U.S. observers, is that socialism in China must be aimed at modernization and industrial development in order to improve people’s lives. This is the biggest task that faces the socialist system in China today. Socialism in the U.S. would not face this problem. This difference necessarily makes U.S. and Chinese visions of socialism worlds apart for the time being, and requires mutual respect between Chinese and U.S. Marxists.

Tak Matsusaka is an activist in the U.S.-China Peoples Friendship Association in Boston.

[1] Part of the increase in per capita income must also be attributed to the increased state purchasing prices for agricultural products.

[2] These per capita income figures are “net” income that excludes agricultural produce consumed by the household. Real income, therefore, is higher.

[3] The 1982 figure for households making more than 300 yuan per capita further breaks down into 29.5% making between 300 and 500, and 6.7% making more than 500. Per capita income brackets are “net” income brackets.[4]

[4] Compiled from figures presented in Beijing Review, Vol. 27, No. 18, p. 16.