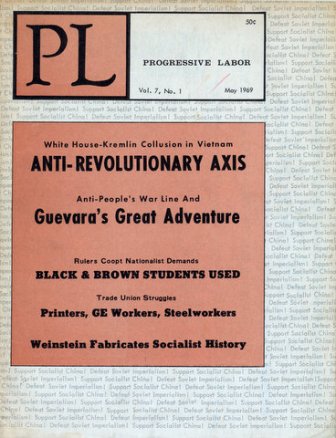

First Published: Progressive Labor Vol. 7, No. 1, May 1969

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

SINCE THE ELECTION of Nixon it is clear that all policies of importance to the United States are going to be made in accordance with its needs and those of the Soviet Union. In other words, U.S.-Soviet collusion will be escalated. Of course, this should lay to rest various suspicions that liberals and fake radicals have about “tricky Dick.”

Before the election, the U.S. Communist Party, Soviet leaders and other liberals were bewailing the fact that Nixon was anti-Soviet. They felt that his election would mean the continuation of the anti-Soviet policies of the Fifties. What these assorted liberals and right-wingers on the Left failed to grasp is the class situation in the world and class strategy of the U.S. in the Sixties. Nixon himself observed that he could no longer be guided by outmoded tactics he pursued in the Forties and Fifties. He was acknowledging the triumph of Soviet revisionism, thus the need for Washington and Moscow to work together now as chief counter-revolutionaries.

We do not mean to imply that contradictions between the two capitalist giants will no longer appear. But these antagonisms, like any others, will take a back seat to the needs of the Soviet bosses and the U.S. ruling class. The U.S.S.R. is no longer a progressive force on the world scene. It has turned into its opposite, hence the collusion between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.

Nixon, therefore, will faithfully execute the policy of the U.S. bourgeoisie just like his predecessors–Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy and Johnson. Humphrey’s defeat signaled no change in basic policy. The U.S. two-fold policy of the carrot and stick goes on. It will try to remain policeman of the world. It will continue its efforts to buy off militants. And it will get more help than ever from Moscow. The latest example is the Soviet attack on Chinese forces.

We have been given another lesson in class rule: Personalities do not dictate the strategy of U.S. imperialism. The needs of imperialism are first and foremost. Recently, we read the following:

One big danger in the President’s trip–he could make the same mistake John F. Kennedy made, by heating up the Cold War at a time when he very much needs Soviet support to help end the war in Vietnam, settle problems in the dangerous Middle’ East, and head off the missile and ABM race.

In fact, Nixon may even need a certain amount of Soviet cooperation in Latin America where the Peruvian military have rushed to resume Russian diplomatic relations, signed a Soviet trade pact and are trying to inflame the entire South American continent against the U.S.

Russian policy is a global policy. If Moscow is following a cooperative line with the United States, it extends from North Vietnam to Cuba and Latin America. If it is not cooperative, there can be obstruction all the way from Cuba to the West Berlin autobahn.

President Kennedy found this out when he spurned the very warm message Nikita Khrushchev sent after Kennedy’s election. He declined to see Khrushchev even though the then Soviet chairman offered to come to New York.

Later, after Kennedy got into hot water with the Cuban Bay of Pigs fiasco, he himself initiated a meeting with Khrushchev in Vienna, where the Russian leader was cold. The meeting was a failure, and U.S.-U.S.S.R. relations skidded downhill to near war over Cuba.

Soviet relations with Nixon started on the same warm basis as with Kennedy. On the day of Nixon’s inauguration, the Kremlin issued an extremely cordial statement welcoming talks on all matters of importance. Nixon replied more cordially than did Kennedy. (Drew Pearson, New York Post)

Pearson also suggests that Nixon’s trip to West Europe might antagonize the U.S.S.R. inasmuch as he is supposed to be talking about European and U.S. strength to ward off the Russians. But Nixon, prior to his trip, called in Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin. “He sent word to Moscow that he means no affront to the Soviet Government.” At Brussels, in the early part of his junket, Nixon publicly expressed his intention to “enter negotiations with the Russians on a wide range of issues.” He also said that “he would consult with them before and during the talks.”

As a matter of fact it may be that Nixon’s trip to Europe is to try to keep Western Europe in line while the main alliance of the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. develops further. After all, it was the Russians who always “understood” U.S. problems in Vietnam. It was the Russians who, according to Averell Harriman, forced the north Vietnamese and the NLF to the bargaining table. The New York Times, on Jan. 27, reported the following:

W. Averell Harriman, former head of the United States delegation to the Vietnam peace talks in Paris, said today he believed that the Soviet Union sincerely wanted a peaceful, neutral Southeast Asia that would serve to block Communist Chinese expansion.

Mr. Harriman expressed hope that in 1969 there would be a de-escalation of the fighting in Vietnam and a start in withdrawal of foreign forces, including the return home of some American troops. But he did not predict that any of these things would happen.

During an interview on a National Broadcasting Company television-radio program, Meet the Press, he said the Russians were “helpful in October and helpful recently” in starting and maintaining the peace talks but gave no details.

Two days later a Times editorial quoted Harriman and extolled the developing U.S.-Soviet collusion.

Actually, most of Western Europe wasn’t too upset watching the U.S. being ground up by People’s War in Vietnam. The licking the U.S. was taking there was helping Western Europe strengthen its economic and political position. Western Europe was more rattled by its own people revolting in France, Italy and, to a lesser extent, Germany, Belgium, Denmark and Sweden.

The Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia is sluffed off by the Nixon bunch, as it was by the LBJ gang, and the U.S. ruling class. They recognize that collusion with the Soviets requires spheres of influence. One hand washes the other, you know. These ideas were spelled out by Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s chief security advisor, in the New York Times (Jan. 27):

“Could a power achieve all its wishes,” Dr. Kissinger wrote in “A World Restored,’’ “it would strive for absolute security, a world order free from the consciousness of foreign danger...” Similarly, on the pending missile talks, he is again asking the larger question: How can we use these talks in order to get to the objective of an understanding on what is permissible and what is not permissible in the conduct of the nuclear powers in the Middle East?

“No power,” Dr. Kissinger writes, “will submit to a settlement, however well balanced and however ’secure,’ which seems totally to deny its vision of itself.... There exist two kinds of equilibrium: a general equilibrium which makes it risky for one power or group of powers to attempt to impose their will on the remainder; and a particular equilibrium which defines the historical relation of certain powers among each other. The former is the deterrent against a general war; the latter the condition of smooth cooperation.”

Dr. Kissinger is apparently advocating that the Nixon Administration try for both with the Soviet Union. His notion seems to be that a missile agreement by itself will not provide even relative security, and a peace in Vietnam, while essential, will likewise not deal with the problem unless there is a larger understanding between Washington and Moscow on the rules of international conduct.

This is clearly only the beginning of the debate, but at least it is better than Mr. Nixon’s former thesis that security can be achieved by a military “superiority” which the Soviets will clearly never accept.

“But since absolute security for one power means absolute insecurity for all others, it is never obtainable as a part of a ’legitimate’ settlement and can be achieved only through conquest.”

He adds that an international settlement which is accepted and not imposed will always appear somewhat unjust to everybody concerned. “The foundation of a stable order,” he concludes, ”is the relative security–and therefore the relative insecurity–of its members. Its stability reflects, not the absence of unsatisfied claims, but the absence of a grievance of such magnitude that redress will be sought in overturning the settlement rather than through an adjustment within its framework.”

In short, Dr. Kissinger wants to concentrate on negotiating an international agreement, not on missile systems alone, or the Middle East alone, but a broad agreement about “the permissible aims and methods of foreign policy,” fully realizing that even so large an achievement would only produce “relative security.

The Nixon gang is now going forward on a whole range of agreements launched by the Johnson group and advocated by Kissinger. The current nuclear non-proliferation pact, which was unacceptable to Nixon during the campaign, is number one on his hit parade now. The U.S. and the U.S.S.R. are going to try to rule the world. Revisionism is the chief ally of imperialism. Revisionism is imperialist ideas within the revolutionary movement.

Vietnam and the current negotiations are a specific example of this collusion and counterrevolutionary policy in practice. Those who reject our analysis and who sincerely believe that the Paris negotiations will lead to a U.S. pull-out must accept all the implications of that belief: The U.S. has abandoned its key strategy of dominating large sections of Asia; the Soviet Union has actually been aiding the Vietnamese, and Soviet interests are diametrically opposed to U.S. interests in Vietnam; and Vietnamese leaders have pressed home the final logic of People’s War–victory for the people and evacuation for the U.S.

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal (Nov. 4) dwells on the meaning of the Paris negotiations:

Communist shelling of South Vietnam’s cities is supposed to end. Hanoi is no longer to send troops across the demilitarized zone to attack allied forces. Red battalions have deteriorated in quality, and their numbers may decline–some Vietcong commanders fear “mass defections” by troops deserting a lost cause.

The rest of the article discusses, at length, military problems the Saigon government faces to stay in power. The article doesn’t deal with a more fundamental problem: How is the U.S. going to prevent revolution in the rest of Asia? This becomes more important as U.S. investments in this area increase. By 1970 Asia, Africa and Latin America will outstrip Europe and Canada as areas for U.S. investment.

Nor does the article raise the need of U.S. military might to help form a ring of steel around the People’s Republic of China. However, it is quite definite about the need for U.S. troops to stay on indefinitely to maintain the balance of power in Vietnam. The U.S. is not going to give up 20 billion dollars in military and business investments in Asia. It is not going to abandon Asian profits. Paris negotiations, as we have said repeatedly, are a fraud against the Vietnamese people and all anti-imperialists. They are aimed at winning at the bargaining table what the U.S. was about to lose to People’s War.

In the Guardian of Jan. 25, Wilfred Burchett hails the victory of changing the shape of the bargaining table:

The Paris conference on the Vietnam war finally moved past the table-talk stage Jan. 18 and reports reaching here indicated the agreement to use a round table was a victory for the Vietnamese liberation fighters.

Other designs, proposed by the U.S. and Saigon, were aimed at setting the precedent that the talks–and therefore the ultimate settlement–were two-sided, “ours” and “theirs.” The round table indicates that there are four parties to the talks.

But the U.S. negotiators, headed by Henry Cabot Lodge, who replaced W. Averell Harriman when administrations changed in Washington, wasn’t seeing it that way. It was sticking to the “our side-your side” fiction, as indicated in the opening statement of Cyrus R. Vance, deputy head of the U.S. delegation, who will be replaced soon by President Nixon.

The debate about the shape of the table would be a farce if the political implications weren’t so tragic. The crucial question is Have the Vietnamese abandoned the strategy of People’s War for the strategy of negotiations or betrayal?

Of course negotiations distort, even change, the war’s issue, which is to defeat U.S. imperialism and win socialism. But people will forget this (the revisionists hope). Already every right-wing group on the U.S. Left has made Vietnamese nationalism its cause of the year (in common with Look magazine). Already the whole scruffy herd of hack journalistic yes-men (those on the payroll and those trying to get on) are turning out reams of articles “proving” that neutralism equals socialism, in an attempt to mislead supporters of the Vietnamese revolution into supporting the negotiations.

The traditional strategy employed by the Vietnamese people’s forces was described by Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap: “A war of this nature in general entails several phases; in principle, starting from the stage of contention, it goes through a period of equilibrium before arriving at a general counter-offensive... Only a long-term war could enable us to utilize to the maximum our political trump cards, to overcome our natural handicap, and to transform our weakness into strength.” (People’s War People’s Army, Hanoi, 1961, p. 29)

Truong Chinh, one of the leading theoreticians and the former First Secretary of the Vietnamese Communist Party, elaborated on what is to be done by the people’s forces in each of these three stages: At the beginning of the first stage the people’s forces are on the defensive, retreating when attacked and attacking only when they have local superiority. “But gradually towards the end of this stage, the enemy-occupied zone being extended and the militia and guerrilla movement being developed, guerrilla warfare comes to play the major role.”

Of the second stage he wrote: “Gradually the enemy’s forces and ours become equal. The enemy’s strategy at this stage is to remain on the defensive while ours is to prepare for the general counter-offensive... Our military and political aim during this stage is to wear out the enemy’s forces, annihilate them piecemeal, sabotage, disturb, give the enemy no peace to exploit the people easily, mobilize the people to wage armed struggle against the puppet administration, oppose the enemy’s mopping-up policy, and strive to annihilate bandits and traitors... By the end of this stage a part of our guerrilla warfare is turned into mobile warfare, which is thereby reinforced.”

Finally comes the third stage of general counter-offensive: ”In this stage the balance of forces having changed in our favor, our strategy is to launch a general counter-offensive and the enemy’s strategy is to defend and retreat... As for us, our consistent aim is that the whole country should rise up and go over to the offensive on all fronts, completely defeat the enemy, and achieve true national independence and unification.” (The Resistance Will Win, Hanoi, 1960, pp. 149, 151, 152, 153).

In late 1966, Le Duan, First Secretary of the Communist Party, wrote a long letter for the purpose of political orientation, and Generals Nguyen Chi Thanh and Nguyen Van Vinh gave political orientation speeches to a meeting of cadres. In all of these three political documents there are unequivocal statements that the balance of forces is still unfavorable to the NLF. All stressed the need for further fighting before equilibrium (stage two) could be achieved.

A year later, in the summer of 1967, the north Vietnamese Army newspaper published a detailed review of the war situation in the south: “The southern armed forces and people have stepped up their offensive, developed their mastery over the battlefield one step further...” (Quan Doi Nhan Dan, July 20, 1967)

There was no claim that mastery over the battlefield had been won, but simply that it had advanced one step. Note that in the last three years of the fight against the French this same newspaper explicitly claimed that the third stage had been reached and the people’s forces were masters of the battlefield.

This same assessment, that the NLF was struggling to move from stage one to stage two, was echoed by the NLF radio at about the same time the above quoted newspaper article appeared. On July 20, 1967, Liberation Radio broadcast Ho Chi Minh’s statement that “The war may last another 5, 10, 20 years or longer.” Despite these assessments the Vietnamese adopted an altogether different strategy in the autumn of 1967. The Tet offensive was the product of the new strategy.

In the autumn of 1967, Liberation soldiers adopted a new course of fighting. Extremely costly battles were fought against heavily reinforced enemy positions. Main force units of the NLF concentrated in the region of the border between north and south Vietnam, and they were massively reinforced with five divisions of the north Vietnamese army. The famous Dien Bien Phu-style seige at Khe Sanh was mounted. None of these developments was consistent with the traditional Vietnamese style of fighting a protracted war at the stage of transition from stage one to stage two, or even when stage two had already begun.

The Tet offensive was similar to the above. On the night when the holiday started, simultaneous attacks were launched against 48 of south Vietnam’s major cities. Local NLF troops made up the bulk of the attackers, with a cutting edge of north Vietnamese regulars and special engineer and commando units. These men were ordered to capture carefully selected public buildings within the cities and hold them. They were promised relief within 48 hours of their assault, and were further assured that many puppet soldiers and policemen would join them immediately, following mutinies. Popular uprisings would take place.

It seems certain that this is exactly what the northern and NLF leaders believed would happen since no people’s army sends troops into battle deliberately misinformed. Nor could the small number of troops committed possibly have held any large city unless the mutinies and popular uprisings occurred. But the general uprising, as Truong Chinh pointed out, is the culmination of stage three’. Following the Tet offensive came the drive against Saigon, which also conformed to the new strategy.

This new strategy of “quick victory,” which was apparent first in the fall of 1967, stemmed from a Central Committee meeting of the north Vietnamese communist party held in April, 1967. That meeting adopted Resolution 13, which stated that the people’s forces should seek “a decisive victory in south Vietnam in the shortest time possible.” This resolution, then, is a clear rejection of the traditional strategy of protracted war. As Le Duan put it in his letter of late 1966: “... tremendous efforts are to be made to obtain decisive victory within a relatively short period of time.”

From the point of view of the Vietnamese communists who supported the new “quick victory” strategy, it was a costly failure. Though it produced important tactical successes and achieved an important psychological victory, the Tet offensive did not end the war, and this was its strategic purpose. But it did hasten the U.S. into negotiations.

The Vietnamese leadership then came up with another military gamble for quick decisive victory: the Saigon campaign. This also failed of it’s strategic purpose–Saigon was not captured and the administration not destroyed. There is strong evidence that a third offensive against Saigon was being prepared in an effort to produce the quick victory when a change in policy intervened.

The Vietnamese leadership had rejected protracted fighting (we will examine why in a moment) and promised quick military victory. This they were unable to produce. Some of the leaders rejected negotiations because they have always been skeptical about winning at the negotiating table what you have failed to win on the battlefield. (Other Vietnamese leaders are for negotiations because they think they can get from them what eludes them in the fighting.) The leadership was up a tree. It was time for a change.

In May, 1968, an important speech was made and broadcast by Hanoi Radio from September 16-20, 1968 and has since been formally adopted as party policy and is now described as ”a new contribution to the treasury of theoretical works on the Vietnamese revolution” (Nhan Dan, Oct. 12, 1968). This speech was no less than a full-scale attack on the old policies. As Hanoi Radio put it, its presentation was followed by “several sessions of heated debate.” In fact the debate lasted four months.

In discussing the war, the speech laid heavy emphasis on the importance of protracted war: “We must grasp the slogan ’protracted war and reliance mainly upon oneself.’” This theme is restated a number of times. In view of the fact that the communist party had officially abandoned the idea of protracted war just 13 months and two military campaigns earlier in favor of “decisive victory in the short term,” this was obviously a deliberate criticism of the communist conduct of the war in the south.

Second, the speech criticized the importance placed on purely military struggle at the expense of political struggle. Political work had not been carried out effectively and this had had a marked effect on the people’s forces’ mass support and the fighting ability of the people’s army. The speech implied that the fighting should be left to the southerners, and the northern troops should withdraw to concentrate on building up socialist construction in the north and suppressing counter-revolution there.

The NLF in the south, the speech implied, was being led by the national bourgeoisie as a result of the error in downgrading political work. The party was not isolating and fighting the principal enemy, meaning that not enough attention was being paid to exploiting the contradictions in the enemy camp by aiming more blows precisely. The speech also indicated that use should be made of diplomatic struggle: “We are currently taking advantage of the contradictions between the doves and the hawks in the American ruling class.” (This, as it turned out, was the decisive point of the speech, leading directly to the Paris negotiations.)

In addition, the speech discussed other matters, such as the erosion of Party control in the north, the infiltration of revisionist ideas, mistakes in the management of cooperatives, mistakes in socialist transformation and the resurgence of small producers.

In other words, the speech ran directly counter to almost every policy in force. Where the speech advocated protracted war, the leadership abandoned it in 1967. The speech advocated retrenchment and increased emphasis on political struggle. The leadership planned massive assaults. The speech demanded stricter Party control, tighter discipline, a purge of the Party. The leadership stressed the value of material incentives, of private agricultural plots, a pragmatic approach to solving problems. It is easy to see why the speech was labeled “pro-Chinese” by the Western press. But this is superficial. What runs deeper is that the speech figured out a way to propose and justify negotiations “from the Left.”

Since the Vietnamese concede they did not carry out political work properly (that means they had the wrong line) and this affected the fighting quality of the troops, we may conclude that this is the reason the leadership had to abandon the strategy of protracted warfare. For this strategy depends in the first instance on political mobilization and high political awareness. If the troops and the people are not prepared by the Party for protracted war, and this is just what the criticism says was the case, they will be able only to fight a war of quick decision if they are able to fight it at all. The political line thus undermined the military struggle. They had either to change the political line or adopt a new military line. As we have seen, they choose a new military line.

But the inescapable conclusion of this self-criticism is that the NLF soldiers were losing morale, the NLF infra-structure was being battered and matters on the people’s side of the war generally were turning bad. Some claim that this conclusion “pushes the U.S. military’s wishful thinking within the antiwar movement” but this argument is with the Vietnamese communists, not Progressive Labor.

When the reality is that you are involved in difficult circumstances, your politics determines your reaction. Some close their eyes and wish it all away. The NLF delegation in Paris tells all comers (each “secretly”) that it is true the NLF infrastructure has been dealt heavy blows. Their conclusion is to take what they can get. They request that the U.S. antiwar forces start a campaign to force Nixon to “bargain in good faith.” All this means is an end to People’s War.

According to the Vietnamese the NLF was dominated by the national bourgeoisie, especially in late 1966 and 1967. But this is the time when the current NLF program was formulated:

1. This is the program that poses neutrality as the goal.

2. This is the program that broadens the idea of “national union” to include all but the very few top Saigon puppets.

3. This program explicitly states that the pro-imperialist politicians will be allowed to pursue their policy aims within the new coalition government as long as they break with the handful of present top puppets.

4. The program states the north Vietnamese are foreigners in south Vietnam, that they have no role to play in settling south Vietnam’s problems, that eventual reunification (to take upwards of 20 years) will come about “peacefully” through “peaceful transition.”

5. This is the program that bars an “independent” south Vietnam entering into military alliances with north Vietnam or China, or the Pathet Lao. Doesn’t this also tie north Vietnam to neutralism? How else will they be permitted to reunify peacefully?

6. This program pledges the NLF to friendly peaceful coexistence with U.S. imperialism.

Now either the American imperialists oppose the Vietnamese revolution or they support it. Either the pro-U.S. puppet politicians oppose the Vietnamese revolution or they oppose U.S. imperialism. How will revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries compose their differences and work out a unified policy that will allow them to serve in the same government?

Some say the NLF program is all trickery. (Who is spreading Washington’s line now?): “Neutrality of any government established by the NLF would only be temporary neutrality with an explicit predetermined direction.” There are three possible directions for the Vietnamese–dominated by the United States, dominated by the Soviet revisionists, or to be revolutionaries. If the puppet politicians (who represent the U.S.) have important positions in the coalition government, or dominate it, then the U.S. will dominate south Vietnam. If “neutrality” is the south Vietnamese coalition government’s policy and “neutral communists” run the show, then Moscow will dominate Vietnam although the form may resemble North Korea. Only if the proletarian revolutionaries are in power can the revolution triumph. But then the country cannot be “neutral.”

Nor can the proletarian revolutionaries come to power now through the Paris negotiations. They do not yet have the power. The counterrevolution (the U.S.) is not yet completely beaten. The Paris negotiations can only accomplish what the NLF program now aims at: ending the fighting and instituting a government with NLF participation. But the proletarian revolutionaries cannot come to power without People’s War continuing. That is why these negotiations are revisionist. They prevent proletarian revolutionaries from coming to power.

Suppose the NLF enters a coalition with the U.S. agents. Suppose the Vietnamese revolutionaries don’t want to sell out, neither Washington’s way nor Moscow’s way (although they are the same in essence). Will the reactionaries in the government (don’t forget that they have power, they have not been suppressed) permit a revolutionary policy without resistance? Will the U.S. stand by with folded hands in the face of this revolutionary policy? Will Moscow not intervene to “prevent the flames of war from being fanned”? Does the murder of 500,000 Indonesian communists mean nothing to supporters of the Paris negotiations? Was it just a peculiar Indonesian quirk carrying no lessons for the rest of us? Does the example of Laos offer no lessons? Is the tragedy of the Congo or Iraq irrelevant? Are these questions “misleading the peace movement?”

A genuine revolutionary would try to help the Vietnamese revolutionaries by using U.S. imperialism’s internal weaknesses to revolutionize U.S. workers. Lenin long ago said to turn the imperialist war into a civil war.

The only progressive orientation for a “peace” movement is an anti-imperialist one. But then it is not a “peace” movement. It is a movement against imperialist aggression. It teaches the working people of our country that the imperialist aggression is aimed at them as well. It splits the U.S. imperialists from the U.S. working people. It does not teach that the imperialists could voluntarily withdraw on a “reasonable” basis. It is by developing the class struggle at home that we express our proletarian internationalism. This can only be done by sinking roots and establishing bases in the U.S. working class for communism, as well as demanding that U.S. get out of Vietnam now. Let us imagine for the sake of the argument what is not true: that the Vietnamese must pause in their struggle because the mistakes they have made in the past cannot be rectified politically. So they negotiate. If we are really concerned with the revolutionary movement at home and in Vietnam we cannot portray that as a victory. We must explain that as a necessary retreat forced by the mushrooming effects of a revisionist line, a retreat leading to renewed fighting in the near future as revisionism is exposed and rejected. That way the working people advance their political understanding. If we present the halt as a “victory” we will never be able to move beyond the real defeat suffered. Far from misleading the U.S. antiwar movement, Progressive Labor is doing the only thing the logic of revolution dictates when it explains the lessons of the Vietnamese struggle and criticizes mistakes.

What is true about Vietnam is that a serious situation obviously exists due to a revisionist military and political policy. Now it seems that steps have been taken to change the reckless military policy. But this is not a certainty. These steps, which supposedly re-establish protracted war as the basis of policy, are phoney. They are the way a right-wing policy cloaks itself to appear “Left.”

That this is true is indicated by the fact that the military line is attached to a revisionist political line: negotiations. The military line is subordinate to this political approach. In all likelihood if one examined the various groupings within the north Vietnamese leadership it would be discovered that the current line has majority support precisely because those who oppose the war altogether value the “Left” cover. Those who desire to keep fighting favor the negotiations because they are afraid of having to start over again; the wrong line must cause them to lose a lot of strength, and the war must be resumed at a weaker and lower level than it has been fought up to now. And those who oppose the negotiations have limited strength to oppose them with. That there is a genuine Left is undoubted, but it must have been overwhelmed in the leadership.

Negotiations will not permit protracted war to emerge as the strategy of the people’s war. You cannot negotiate and at the same time convince the troops to make the sacrifices required by protracted war. This does not mean the level of the fighting will not rise. It will. It is standard Vietnamese negotiating strategy to step up the tactical attacks to influence the negotiations.

This is the main reason for the current NLF offensive. The great power of the masses is being squandered by negotiations and a military strategy dominated by negotiations.

Tactical attacks do not equal strategic direction. The strategy is peaceful maneuvering. The Vietnamese have not yet abandoned a revisionist political line. This is what the news out of Hanoi is saying. This is why some here offer sound and fury without revolutionary content.

So we can deduce that the Vietnamese leaders have abandoned People’s War. We feel that the evaluation of People’s War in Vietnam is the main way we can judge the intentions of the Vietnamese leaders. The perspective for neutrality cannot solve the problems of the people. Only the dictatorship of the proletariat can do this. Was socialism or neutrality the outlook of the communist party leaders? If the outlook was for neutrality, the strategy of negotiations was bound to win out. If the outlook was for socialism then the strategy of People’s War would have triumphed. The logic of a people’s war cannot be to fasten bourgeois national ideas on the people. It must be to establish socialism. Can socialism and freedom be built in coalition with Saigon? Can socialism be won with U.S. imperialists and the Soviets present?

Only a long fight to the end can establish socialism. We believe this is the desire of the people. They have been fighting foreign imperialists for many decades–first the Japanese, the French and now the U.S. Do we really believe the people of Vietnam will settle for anything less than socialism? When the sellout becomes apparent, People’s War will surely reassert itself. Didn’t the error of negotiations of 1954 give way to People’s War? The errors of ’54 have become the betrayal of’68. This is the logic of repeated errors.

Naturally, Soviet “aid” was designed to strengthen revisionist groupings in Vietnam. It is no accident that the Soviets were able to speed up Vietnamese participation at Paris. Of course the Vietnamese were the first to hail Soviet aggression in Czechoslovakia. Of course the leaders of Vietnam are silent about Soviet military aid to reactionaries in India, Indonesia, Egypt, Algeria, etc.; nor will they condemn Soviet aggression against China. This is the logic of neutrality–neutral at the expense of the masses. And neutral on the side of revisionism and imperialism.

To be on the side of the workers and oppressed people means the exposure of all that impedes their advance. There is no neutrality in the class struggle. The choice ultimately is either nationalism (capitalism) or socialism (the dictatorship of the proletariat).

Therefore, in viewing Vietnam we can see the continuation and escalation of the Soviet-U.S. collusion under Nixon. It is easy to see the counter-revolutionary interests of the U.S. and the U.S.S.R.

If this collusion isn’t fought, if both sides of the counter-revolutionary axis aren’t fought, if “aid” is accepted from either one, if all Soviet tactics for peaceful coexistence (which equal counter-revolution) aren’t exposed, it will not be long before you move to the antirevolutionary camp. The fight against revisionism is one of life and death–or socialism and freedom vs. imperialism and oppression. This is what the Soviet-Chinese border fighting is all about.

Many genuine antiwar forces have been forced, under the manipulation of the local troika (Communist Party, Socialist Workers Party, pacifist bunch) and the tutelage of the Moscow-Hanoi-Washington axis, to fight for “successful” negotiations. This would leave the Vietnamese people with more fake leaders imposed by Washington and Moscow and continued U.S. presence and oppression. What most antiwar forces want and what the Vietnamese want is for the U.S. to get out of Vietnam now! It is not a coincidence that the Nixon Administration can adjust so easily to the LBJ negotiations. Capitalist newspapers are always singing about the smooth transition of power in general, and the smooth transition in Paris from Harriman to Lodge.

The important breather the U.S. has gained in Vietnam will be used to intensify the attack on people at home. Naturally, the hardest hit will be the Black workers and Black people who are fighting the bosses. Recently, Nixon has threatened various militant students with police terror and other oppression if they don’t stop their efforts. While we are not in favor of all student movements, especially Black nationalist ones, we are in favor of the antiracism-anti-imperialism that motivates all of them.

Senator Muskie has given us a glimpse of what is in store. Many politicians, including the various fakes in the anti-war movement, have been popping-off about how the billions spent in Vietnam would be spent for the people “if only the war ended.” He referred to this idea as “wishful thinking.” He spoke of the need for continued presence in Vietnam and the high cost of this. He implied that similar U.S. commitments around the world require a tremendous cost.

The U.S. has no idea of abandoning its foreign interests (imperialism). We are sure that it will back these commitments to the hilt (because maximum profits are made from them). And the U.S. is helped by the force of the Soviets. Workers here will continue to pay not only the high taxes this requires, but even higher taxes as U.S. bosses .fight people around the world who try to free themselves.

What is also in store for workers is a continuing squeeze to underwrite U.S. foreign policy. Higher prices, less wages, speedup and more automation are the order of the day.

Workers are going to have to hit the bricks more often and longer to ward off ruling-class blows. Recent strikes around the country in longshore, steel, printing, teaching, etc., show that workers are not going to take more attacks lying down. As the Nixon Administration tries to carry out more of the same in Vietnam and elsewhere, it will find opposition to imperialism in workers’ ranks expressing itself far beyond present limitations. U.S. workers are hot going to pay willingly for the expenses of imperialism. They are not going to fight and die so that U.S. bosses can pile up bigger profits. This is one reason there is so much blather about changing the draft. But no gimmick will succeed.

No matter how Nixon tries to soft-peddle the contradictions within the U.S. and its allies he will still run into a pack of trouble. U.S. rulers aim to rule’. They are relying on Soviet bosses to help them. The Soviet aggression in China is part of that deal. Workers and oppressed people at home and around the world will fight back. What the bosses fear most is that these struggles will surpass anything in the past. They fear these struggles will become revolutionary–Marxist-Leninist. People are learning that partial, limited struggle won’t fill the bill. They are learning the answer to a crucial question: Which class holds state power? The dictatorship of the proletariat will triumph! Workers and oppressed people are learning from setbacks in Vietnam and elsewhere. Soviet and U.S. bosses have something to be fearful about.