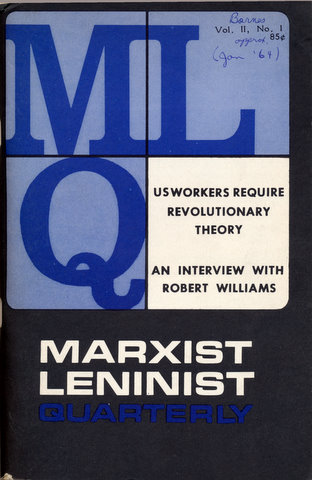

First Published: Marxist-Leninist Quarterly, Vol. II, No. 1, no date [approximately January 1964]

Transcription, Editing and Markup: Paul Saba

Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above.

Editor’s Note: William Z. Foster was born, the son of a carriage washer, in Taunton, Mass., on Feb. 25, 1881 and died in Moscow on Sept. 1, 1961. This article is written in commemoration of his birthday and in appreciation of his many contributions to the American working class and the international socialist movement.

* * *

At this time when Marxism-Leninism is engaged in a worldwide struggle against modern-day revisionism it is particularly appropriate that American Socialists pay tribute to the memory of William Z. Foster and draw upon the rich legacy of experiences which he left us. Certainly his struggles against revisionism are an important part of this legacy and though, since his death, the attempt has been made to metamorphosis Foster into a sycophant of revisionism and, later, to consign him to oblivion, American Socialists cannot permit either of these stratagems to go unchallenged.

During his 60 years in the socialist movement here, Foster took an active part in all of the major struggles against revisionism, leading the offensives against Lovestoneism, Browderism and Gatesism. In each of these, the ideological position he supported was basically correct while those taken by Lovestone, Browder and Gates were basically incorrect and a gross distortion of Marxist-Leninist principles. For his role in these, Foster deserves great credit and, notwithstanding mistakes or shortcomings, successes or failures, he readily stands out in this whole period as the ablest and most consistent fighter against revisionism.

Because the U.S. is the stronghold of world capitalism, Foster recognized that the socialist movement here is particularly susceptible to revisionist doctrines which are based on an overestimation of the strength of capitalism and seek to attribute to it progressive virtues. He wrote, “The capitalist system in this country is a collossus with feet of clay. American imperialism will lose ideological and organizational control of the workers as its dominant world position weakens. And because of the inevitable deepening of the general crisis of capitalism, this decline is bound to come.”[1]

Foster had a high regard for Marxist-Leninist theory as a guide to action and knew that, without a correct theory, the American workers could never achieve socialism. Both from first-hand experience and his studies of American history, he saw that the development of the socialist movement in the U.S. had been seriously retarded by its entanglement with muddle-headed “theories” and that, in spite of their claims to the contrary, neither the Socialist Labor Party nor its successor, the Socialist Party, had ever devised programs that were anything more than highly distorted and grotesque caricatures of Marxism.

Much more clearly than his contemporaries however, Foster saw revisionism as the corruption of Marxism-Leninism by the infusion of pro-capitalist ideas and realized that capitulation to or compromise with revisionism is a betrayal of the working class and its struggle for socialism. Lenin warned against allowing the lessons of revisionism to be forgotten and, writing in 1908, stated that “recent theories of the revisionists are being forgotten by everyone, even, it seems, by many of the revisionists themselves. But the lessons . . . must not be forgotten.”[2] The left in our country has, to be sure, repeatedly shown an unseemly haste to sweep its revisionist mistakes under the rug and forget about them, instead of first drawing the full lessons and using these to fortify itself. Foster, however, wrote many articles about the struggle against revisionism and generalized them in his History of the Communist Party in the U.S.

Foster’s historical analyses of these struggles are quite helpful, being more accurate and objective than other available sources. Yet it cannot be said that they are by any means final or complete. They suffer from the same general limitations and shortcomings that characterized the left-wing movement in this period. Though more far-seeing, critical and self-critical than other C.P. leaders, Foster shared in considerable measure the illusion that the party had already achieved a correct theory and was, generally speaking and except for some temporary aberrations, properly applying it to the specific conditions prevailing in the United States. Thus, on the one hand, he overestimated the degree to which the party had developed its understanding of theory and, on the other hand, underestimated the danger of opportunism, reformism and revisionism. Though Foster fought against these opportunist tendencies with greater vigor and understanding than other C.P. leaders, it is true that even he was usually slow to recognize revisionism until it reached an advanced stage and that the struggles against revisionism were never carried through to a definitive ideological resolution but only to a formal, temporary, organizational accommodation. There were, of course, many reasons for this and these deserve careful analysis by U.S. Marxists. Certainly, one of the most fundamental is the traditional American contempt for theory, the strong appeal of pragmatism and empiricism, which in the C.P. tended to stifle the free discussion of Marxist-Leninist principles and, notwithstanding claims to the contrary, made inevitable the sacrifice of correct principles to organizational expediencies.

Foster’s proletarian origin and his early experiences as a worker helped to prepare him for his later responsibilities as a labor organizer and socialist leader. At the age of ten, Foster got what he called his “first real job” and thereafter tried his hand at all sorts of work, such as mixing fertilizer, driving mules, cooking for Texas ranch hands, operating a New York trolley car, inspecting and repairing railroad cars. At the age of twenty, he went to sea, sailing on “square riggers”, and then became a migrant worker, “on the hobo” as it was then called.

Foster was every inch a worker and unswervingly loyal to his class He embodied all of the best qualities of the American working class and was indeed its finest son. “From my earliest youth I have always felt great pride in being a worker. . .,” Foster wrote in his Twilight of Capitalism, “If I were starting my life all over again, I would take the same course as I have done,” he declared.

At the age of 19, after listening to a street speaker in Philadelphia, Foster said, “I began to count myself, from that time on, a Socialist.” But it was not until 10 years later that he joined a socialist organization, the I.W.W., a syndicalist group, and not the Socialist Party which then claimed to be the standard bearer of Marxism in the U.S. At the time, Foster had gone to Spokane, Washington, to take part in the militant free speech fight being waged by the I.W.W. and, while in jail there, made his decision. “It was chiefly,” he explained, “disgust with the petty bourgeois leaders and policies of the S.P. that made me join the I.W.W. ... It was an easy step for me to conclude from the paralyzing reformism of the S.P. that political action in general was fruitless and that the way to working-class emancipation was through militant trade union action, culminating in the general strike. This conclusion was a serious error, my confounding political action as such with S.P; opportunism, and thus casting aside the political weapons of the working-class. It took me many years to correct this basic mistake.”[3]

Lenin sometimes spoke of revolutionary syndicalism as a special form of revisionism, which he called “revisionism from the Left.” In this sense we can say that Foster’s first, fight against revisionism was with himself. He broke with the I. W.W. in 1912 after an unsuccessful effort to persuade the I.W.W. to give up its dual union tactics and then, after two years, of difficult but not very rewarding work in trying to organize the Syndicalist League of North America, Foster became closely associated with the group of militants in the Chicago Federation of Labor, then the most progressive labor council in the country. It was here that Foster earned his reputation as the outstanding labor organizer and strike leader of this period. He led the 1917-18 drive that succeeded in organizing 200,000 workers in the meat-packing industry, the first mass production industry in the U.S. to be unionized, and in 1919 he led the great steel strike, which, though broken after three months of heroic resistance, won the 8-hour day and other gains. Most important, these struggles ushered in the policy of industrial unionism, a correct and urgently-needed policy in the conditions then prevailing and one which shaped labor history by helping to make possible the later organization of the C.I.O.

The great October Revolution dispelled Foster’s lingering doubts and caused him to switch from anarcho-syndicalism, which he took up after syndicalism, to Marxism. To see for himself the birth of the first socialist nation, he made a trip to Russia, heard a speech by Lenin that impressed him both by its simplicity and wisdom and, while still there, immersed himself in Lenin’s writings. “After more than twenty years of intellectual groping about,” he wrote in Pages From A Worker’s Life, “I was at last, thanks to Lenin, getting my feet on firm revolutionary ground.” Upon his return to the United States in 1921, Foster joined the newly-formed Communist Party.

Unity within the new Communist Party proved to be short-lived. Sharp factional strife erupted in 1923 and continued until 1929. Over most of this period, the party split down the middle into two warring camps, almost evenly divided. The usual line-up was: on the one side, the Foster-Bittleman-Browder-Dunne-Cannon group and, on the other, the Ruthenberg-Pepper-Weinstone-Lovestone group.

The quarrel arose over the question of how the left forces should try to influence the 1924 elections when LaFollette ran on the Progressive ticket against the ultra-reactionaries, Coolidge: (R) and Davis (D). Instead of endorsing the LaFollete movement as it should have, the Communist (Workers) Party, fearful of becoming engulfed in the LaFollette upsurge, sought to rouse left-led labor groups in support of a Federated Farmer-Labor Party. In so doing, the Communist (Workers) Party succeeded only in isolating itself from the broad masses of workers and farmers and eventually found itself committed to a party that nobody really wanted.

Alarmed by these developments, Foster called the farmer-labor party a mistake, pointed to the needless break with the Fitzpatrick-led labor groups in the powerful Chicago Federation and urged that measures be taken to correct the narrow, sectarian labor policies responsible for the error. The Federated Farmer-Labor Party never took the field and instead the Communist (Workers) Party put up its own candidates. But a minority group within the C(W)P led by Ruthenberg and Pepper refused to admit that the national farmer-labor party was a mistake and went on to defend the whole political line that spawned this still-born orphan. Many of the arguments pro and con strongly resembled those later heard in the 1948-52 period of the Progressive Party when the mistake was again made of unduly pressuring and needlessly isolating left-wing trade unions. This dispute over third party tactics, though mediated by the Comintern was never fully resolved, soon spread to all sorts of questions, such as: The evaluation of imperialism and the development of capitalism, work in the trade unions, united front tactics, the Negro and agrarian questions, attitudes towards the Socialist Party and other groups, the organization of the Communist Party, etc. So bitter were the fights that questions were not discussed or decided on their merits but were continually being referred to the Comintern.

Not until the end of the 1920s did these factional fights move to a showdown. In 1928 James P. Cannon was expelled from the C.P. for supporting Trotsky’s left-deviationist doctrine. Upon his return from the sixth world congress of the Comintern, which had turned down an appeal from Trotsky in exile, Cannon began clandestinely distributing Trotskyite materials. Though Cannon had been a member of their group, Foster and Bittleman preferred the charges against him of disseminating Trotskyite propaganda, advocating withdrawal from existing trade unions, abandoning the united front and fomenting disruption. Eventually about 100 of Cannon’s followers were also expelled and, under Cannon’s leadership, formed an opposition league which later became the Socialist Workers Party, affiliated to the Fourth International.

In 1929 the Lovestone group of right opportunists, numbering some 200 members, were also expelled after their doctrine of “American exceptionalism” had been rejected by the Comintern and they, refusing to abide by the outcome, then sought to split the U.S. party. The nub of Lovestone’s theory was that U.S. capitalism was about to enter its “golden era” and that, while the general crisis of capitalism was becoming more intensive elsewhere, prosperity would continue upwards indefinitely in the U.S. The Foster-Bittleman group opposed as revisionist the whole Lovestone line with its perspective of continuous, uninterrupted prosperity, abatement of the class struggle and the automatic solution of the Negro question through the industrialization of the South.

The inability of the American party itself to resolve the Lovestone crisis of revisionism was, of course, a measure of its ideological weakness. At the CPUSA’s convention on March 10, 1929, the Lovestone-Pepper group had a majority of the delegates and the Foster-Bittleman group a minority. After a futile effort at discussion, the convention voted unanimously to refer the issues raised by Lovestone to the Comintern. There, a commission made up of representatives from various parties, characterized Lovestone’s “theory” as: “a crisis of capitalism, but not of American capitalism; a swing of the masses to the left, but not in America; a necessity of struggling against the right danger but not in the American Communist Party.” It was at this Comintern session that Stalin made his well-known prediction of the “ripening of the economic crisis in America” and a few months later the onslaught of the Great Depression added its refutation to Love-stone’s “golden era” of uninterrupted prosperity. Following his opportunist bent, Jay Lovestone went on to become an advisor to George Meany on how to subvert labor movements internationally in the interest of U.S. imperialists.

Although the methods by which these purges were carried out–by means of outside intervention and action from the “top-down”–left much to be desired, they nevertheless rid the party of its chief factionalists, its left sectarian deviationists and its right opportunist revisionists, thus enabling it to prepare itself to some extent for the Great Depression which struck with furious force just four months after Lovestone’s expulsion. The depression stirred the masses into motion and transformed the C.P. into a dynamic, militant organization. It was the only party that undertook to organize the unemployed and to champion their fight for jobs and relief. It led mass demonstrations and hunger marches, set up Unemployed Councils and initiated the demand for unemployment insurance; it led ex-servicemen in a National Bonus March on Washington; it penetrated the South, upholding the rights of the Negro people and arousing broad public support to win the Scottsboro, Herndon and other cases; it helped to organize the unorganized urban workers, agricultural workers, sharecroppers and farmers, was active in the big strike movement of 1934-36 and in the organizing campaign that led to the establishment of the CIO.

During the 1929-33 years of deepest crisis, the C.P. raised its membership from 10,000 to 18,000, a substantial increase though not in proportion to the influence it then wielded. This was actually the high point of the C.P.’s development, the period of its greatest strength, even though its membership continued to increase, reaching 80,000 in 1944 when the balloon of Browderism burst. The recruits during the depression came chiefly from the ranks of the proletariat, thus strengthening the composition of the party and countering tendencies toward petty bourgeois opportunism. In fact, the chief mistakes at this time were of a leftist nature, as indicated by such slogans as “The revolutionary Way Out of the Crisis” and “A Workers and Farmers Government.” Even after allowing for mistakes, however, it must be said that the program developed in this period marked a major advance. It came closer to being a correct Marxist-Leninist program for the U.S. than anything that had been developed during the previous 70 years.

As economic conditions began to improve, however, the C.P. under Browder’s leadership began, slowly at first and then faster, to move toward the right on a course that brought it in 1944 to Browder’s Teheran dream of “progressive capitalism.” Many of the revisionist ideas that Browder later used in extolling the virtues of his postwar Teheran world in which the class struggle would virtually disappear began to take form in his early efforts at rewriting U.S. history. Though some objections were made at the time, neither Foster nor any other C.P. leaders were aware of where Browder was heading, however, as early as 1934, Browder issued the slogan, “Communism is Twentieth Century Americanism” and, as Foster noted, “After Browder’s writings were saturated with his ’all-class’ conceptions of ’American democracy.’” Browder, like Kautsky, made no distinction between bourgeois democracy and proletarian democracy and sought to present socialism as a “natural” evolutionary development of capitalism rather than as a revolutionary break with capitalism. Thus, he got the CP. to write into the preamble of its constitution that Jefferson’s principles “lead naturally and inevitably to the full program of the Communist Party, to the socialist reorganization of the U.S.”

During World War II Browder pressed for a program of national unity that called for “uniting the entire nation, including the biggest capitalists, for a complete and all-out drive for victory.” In practice, this meant that labor should commit itself to a “no strike” pledge and demand no voice in the wartime government, that the Negro people should abandon their fight for jobs and rights and that the party should give up its vanguard role and tail behind the Roosevelt Administration–i.e., total capitulation to monopoly capitalism. Browder initiated or sponsored a whole series of moves that systematically weakened the class composition of the party and opened the way for petty bourgeois opportunism–e.g., eliminating shop units, shutting down left-led mass organizations in the guise of achieving “broader unity’, making deals with the rightwing labor cliques, liquidating most of the CP. in the South and finally, his grand coup, getting the CP. to dissolve itself into a “non-partisan association,” “a political education association,” the Communist Political Association.

In unfolding his Teheran perspective, Browder said, “Capitalism and socialism have begun to find the way to peaceful coexistence and collaboration in the same world.”[4] Though the Teheran agreement of Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin was essentially a military one, Browder exalted it into a plan for a postwar utopia in which contradictions would fade away between imperialist and socialist countries and between imperialist and colonial countries. “It is the most stupid mistake to suppose that any American interest, even that of American monopoly capitalism, is incompatible with the necessary people’s revolution in Europe,” he declared.[5] With a few quick strokes of his pen, Browder went on to liberate the colonial and semi-colonial countries as follows: (1) “America, with by far the strongest capitalist economy in the world, must have enormous postwar markets for its products,” (2) “Colonial or semi-colonial regimes provide narrow and restricted markets, while independent, self-governing nations provide expanding markets” and (3) the U.S. must have a policy “directed, therefore, toward abolishing the colonial system and its replacement by a system of free, self-governing, unified nations.” While allowing that some old-fashioned fuddy-duddy capitalists might balk at these changes, Browder was convinced that a sufficient number of big capitalists, especially here in the U.S., would welcome them, thus assuring peaceful transitions to socialism in Europe and colonial liberation in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Whereas Lenin described imperialism as parasitic, decadent and moribund, Browder, who shunned the word “imperialism,” said that American capitalism “retains some of the characteristics of a young (Emphasis his–Ed.) capitalism,” that it would play a “progressive role” and be a force for peace for a long time.

Many of the ideas set forth by Browder are strikingly similar, some almost identical, with those being offered today by Khrushchev as “creative Marxism.” Though Browder later repudiated Marxism, he maintained in 1944 that his Teheran thesis was “true to basic Marxian principles” though “not an ’orthodox’ Marxian program“–“an un-precedented policy” for “an unprecedented situation” and not “dogmatic’ Marxism. Teheran was to Browder what Khrushchev said a Summit Conference could mean to the world; both put a heavy, one-sided emphasis on the negotiation of an agreement by the heads of state of the most powerful capitalist nation and the most powerful socialist nation as the guarantee of world peace, thereby underemphasizing and discouraging the people’s struggles. Both distort Lenin’s correct principle of peaceful coexistence between countries with different social. systems into an overall program or general line which would exclude assistance to and cooperation with the revolutionary struggles of the oppressed people and nations. Both give U.S. imperialism a “new look,” a benign, peaceful visage and both magnify the slim, but never yet realized possibility of a peaceful transition from capitalism to socialism as something approaching a certainty. Browder dissolved the CPUSA and Khrushchev has already proposed an end to the Soviet Union’s dictatorship of the proletariat.

At the conclusion of Browder’s long-winded Teheran report on Jan. 7, 1944 before the expanded meeting of the C.P.’s national committee, attended by some 500 party workers, the floor was, so it was said, opened for discussion. But when Foster put his name on the speakers’ list, he later wrote that “several members of the committee strongly urged him not to do this,” apparently with the threat of expulsion. They also said that “Browder had spoken without a previous review of his speech and that the whole matter would be taken up shortly for reconsideration by the Political Committee.” Such was the status of free discussion: only Browder had the right to speak and only those who agreed with him had the right to discuss what he said: Even the latter was not always permitted, however, for at the CP. convention of May 20-22, 1944, Browder’s motion that the CP. liquidate itself was adopted without discussion.

After waiting in vain for the Political Committee to meet, Foster wrote in January 1944 a letter to the national committee stating, “In this (Browder’s–Ed.) picture, American imperialism virtually disappears, there remains hardly a trace of the class struggle, and socialism plays practically no role whatever.” Foster was the only one in the national leadership of the CPUSA to challenge Browder’s overall Teheran line as revisionist before Jacques Duclos, secretary of the French C.P., wrote a highly critical article in the April 1945 issue of Cahiers du Communisme.

Foster explained that he did not take the fight against Browderism to the membership because it would have led to a split and he was sure the members themselves, even without Duclos’ article, “would eventually have cleared the Party of this political poison.” “But,” he added, “it would have been a difficult process, probably involving a serious Party split.” As later events showed, Foster was far too optimistic about the ability of the party to cleanse itself of the poison of Browderism, which had gone deeper than he realized. In actual fact, it was the Duclos article rather than any internal party struggle that brought the political committee of the C.P.A. to reject by a two-thirds vote, later made unanimous, the Browder line and to summon an emergency convention which endorsed its actions and restored the C.P. as a party. Thus, as in the case of Lovestone’s revisionism, the pressure for correction came from outside the organization and the rejection of Browderism, like its acceptance, was carried out from the top-down with the result that, while party unity was formally preserved, ideological unity was still lacking. Though Browder was later expelled, the national leadership remained much the same, having merely been reshuffled, and district organizers were in some cases moved from one area to another.

Foster was wrong in thinking that the worst thing that could possibly happen would be a split in the party. The worst thing, as later events proved, was the failure to do everything possible to scourge the party of petty bourgeois opportunism, the effect of which was to sacrifice principle for the sake of unity. After the removal of Browder from leadership and Foster’s re-instatement as national chairman, Foster could and should have insisted upon a vigorous, overall struggle against revisionism throughout the party and into every aspect of its work. Instead, he chose to accept at face value the preciptious, mechanical reversals, the sudden disavowals of Browderism, by the national and state leaders of the party and, to save” these leaders en bloc. Foster interposed his authority, assuring the membership that these leaders had never become seriously tainted by Browderism. The result of Foster’s intervention was to render impossible any effective follow-through in the struggle against Browderism and to continue, with only minor changes, the former leadership. Foster’s purpose was, of course, to maintain party unity and while unity is always important to a Marxist-Leninist party, it must never be given priority to principle.

Foster’s intervention on behalf of the leaders, to “save” them from criticism, also indicated an underlying incorrect attitude, one which had long been held and did considerable damage to the C.P., toward the relationship of “leadership” to “membership.” It is no exaggeration to say that, within the C.P., there were two organizations, quite separate and distinct: the leadership that enunciated policies and the membership that was supposed to carry them out. After Browder’s removal, no fundamental measures were taken to change this or other incorrect methods of work, to overcome bureaucracy or to stem revisionism at its source by undertaking to transform the party from a petty bourgeois organization into a proletarian one.

So long as the U.S. party was able to rely upon the Comintern for guidance (incorrect and over-dependent as this relationship, often proved to be) it was able to conceal to some extent its internal weaknesses and opportunist vagaries. After the death of Stalin, however, these weaknesses became increasingly apparent and as Khrushchev began to put forth his revisionist views, all of the pent-up revisionist ideas so long harbored by the leaders of the U.S. party poured out.

The postwar world was quite different from Browder’s dream world. Foster’s warning that U.S. imperialism was making a drive for “world mastery” proved correct. With Churchill’s help, U.S. imperialists unleashed their Cold War policy which soon developed into a large-scale offensive in Korea and in an atmosphere of McCarthyism and frenzied anti-communism, the government carried out mass arrests and deportations under the Smith, McCarran and other so-called anti-subversive Acts. With this sharp change in the objective situation and the heavy blows of the government against the left, the C.P., still reeling from and shot through with Browderism, quickly fell into the opposite error and committed costly left-sectarian mistakes, especially of a tactical nature. Some of the worst of these were: (1) the inflexible tactics used in opposing the Marshall Plan which led to the expulsion of left-led unions from the CIO, (2) the methods used in promoting support for the Progressive Party in 1948 as a third party from labor and other groups which cut into their mass contacts and (3) the so-called security measures taken to protect the CP., such as arbitrarily lopping off 75% of the members and abandoning others.[5a]

It was Khrushchev’s “secret” report to the 20th Congress in 1956 that reversed the leftist course of the CPUSA and sent it again careening into revisionism, which this time was called “Gatesism” though “Titoism” and “Khrushchevism” might be more appropriate. Seizing upon the left sectarian mistakes that had been committed during the Cold War, the right opportunists in the CPUSA, some of whom were loosely grouped around John Gates, began to press for liquidation of the party and renunciation of any vanguard role. Gates urged “A party of a new type,” geared to the “totally changed situation” in which the path toward the triumph of Socialism here is one of peaceful and constitutional struggle.[6] That the majority of the national committee of the CPUSA was at the time in general agreement with such views is shown by the 1956 draft resolution it approved calling for a “new mass party of socialism,” deleting the reference to “Marxism-Leninism” from the party’s constitutional preamble and abandoning responsibility for the vanguard role. Though the party leaders paid little attention to Foster’s views at this time and the articles that he sent to party organs from his sickbed generally went unpublished, he did manage to get one article published at this time in which he warned the membership, “As the Resolution now stands our party ceases to be specifically a Marxist-Leninist Party.”[7] In this article Foster noted the resurgence of Browderism by those who “argue that if we had stuck to Browder’s line the Party would have avoided the bitter persecution 0f the cold war period.”

The uprisings in Poland and Hungary gave further stimulus to the revisionists here and so great was the confusion within the CPUSA at this critical juncture that the national executive committee could think of nothing better to say about the Soviet Union’s action in Hungary than that it “neither approved, nor do we condemn” the action. Foster got up from his sickbed to lead the fight against revisionists and it was largely due to his efforts that they were repulsed on this occasion. They were not, however, fully exposed or defeated. They backed down, temporarily at least, putting the full blame for “Gatesism” on Gates, the editor of the Daily Worker, who was expelled and on a small group of his fellow journalists, who resigned. While anti-revisionist insurgents did succeed in forcing some changes at this time in the national leadership, most of the top leaders managed to survive the storm and, even those removed from top leadership positions were soon brought back.

Foster himself was not immune to the revisionist ideas that Khrushchev began unloosing in this period and, in fact, lavishly praised Khrushchev as a “brilliant” Marxist-Leninist theoretician. But when the party here was threatened with liquidation and Marxism-Leninism was earmarked for elimination, Foster could see revisionism for what it was and plunged into the fray. Though Foster’s ability to identify revisionism which correctly was better than that of other C.P. leaders, it must be admitted that in the cases of Gatesism and Browderism even he did not fully recognize their revisionist character until after they had reached the stage of virulency. In neither case even after a correct diagnosis, did he or others offer any effective cure or recommend any preventive therapy for use in the future.

In the decade following the repudiation of Browderism, Foster was apparently under the illusion that the C.P. had quite thoroughly rid itself of Browder’s influence. When Gatesism erupted in 1956, he commented that “strong Right tendencies, for the first time in a decade, have shown themselves in the Party.” But where had these “tendencies” come from? Foster did not say. Among the ideas put forward by the right opportunists at this time were: (1) abandonment of the dictatorship of the proletariat; (2) repudiation of Marxism-Leninism in theory and in practice as left sectarian; (3) renunciation of a vanguard role and of the revolution; (4) liquidation of the party; (5) denial of the war danger; (6) soft-pedaling of the Negro question; (?) tailism in the labor movement. So unrestrained was this outpouring of reformist obscenity that even Foster was forced to recognize carry-overs from Browderism and observed, for example, that “some comrades...would resurrect what was ’good’ in his (Browder’s) system” while “other comrades, however, are prepared to accept Browderism hook, line and sinker, justifying his whole revisionist system and they are running extensive Browderite material in our Party press.” Yet Foster, here as in the fight against Browderism, failed to draw the seemingly glaring conclusion that a major assault against right opportunism was necessary.

Foster’s strength and also his weaknesses reflected the level of development of the movement at this time and his contributions were in any case “its best.” In the struggle against Gatesism as in those against Browderism and Lovestoneism, he played a leading role, if not the leading role. That the struggles against Gatesism and Browderism did not achieve their purpose cannot be blamed solely on Foster, of course, as some people would have us believe; the main blame must be accorded tt the opportunist leaders of the C.P.

Lenin once wrote, “The only Marxist line in the world labor movement is to explain to the masses the inevitability and necessity of breaking with opportunism...” and he added that the only way to do this is for communists to “go down lower and deeper to the real masses.”[8] Unfortunately, the C.P. did not do this. After neither the Browder nor the Gates struggle did the party prove itself capable of initiating any fundamental changes that might have helped to transform it into a vanguard party of the proletariat but was instead content with a few changes in the palace guard. The right of the members to discuss freely, to voice their criticisms and to dissent was never established; petty bourgeois opportunism was still rife; the stultifying atmosphere of bureaucracy, sectarianism and commandism remained.

Shortly after Foster’s death in the Soviet Union on Sept. 1, 1961 a funeral service was held in New York at which Gus Hall and other CPUSA spokesmen offered their “tributes.” None of these “tributes” took any notice of Foster’s struggles against revisionism; there was not even a mention of Browderism, his most important anti-revisionist fight. This glaring omission was an indication of the extent to which the CPUSA itself had capitulated to revisionism. In his remarks Gus Hall even sought to claim Foster for the revisionists by saying that Foster had “presented new and further possibilities for a peaceful transition to socialism.” Hall did not mention the qualifications that Foster, even at the time of the Smith Act trials, had been careful to add, namely: “The capitalists always go to every possible extreme of violence to crush socialism.”[9] Unlike those who try to delude the workers into believing that peaceful coexistence will somehow guarantee a peaceful transition to socialism in the U.S., Foster wrote: “No one who knows the American capitalist class, with its long record of war aggression, brutality in strikes, slaughter of workers in industry, persecution against the Negro people, etc., can doubt but that the reactionaries would use every available means of Social-Democratic treachery and of outright violence to prevent or destroy any government (emphasis added–Ed.) that cut into their rule and into their robbery of the people.”[10]

Before Foster died, the Great Debate had already begun and, though quite ill, he followed it carefully. At the end of 1960 just before he left for Moscow to seek medical treatment, Foster said that he intended to go on from there to China. Of the book then recently issued by the Communist Party of China, Long Live Leninism, he declared, “I’ve read it carefully–more than just once–and agree with every word in it.” He was greatly concerned over the growing rift and was already convinced on the basis of what had by then appeared that there would be a long and difficult struggle. Taking issue with those here who tried to suppress the distribution of Long Live Leninism and to dismiss the arguments of the C.P.C. as the rantings of madmen, Foster expressed the opinion that American communists should “make a careful study of what the Chinese are saying.” He was obviously quite impressed by the arguments that the Chinese were advancing and disturbed by the attitude of those here who sought to misrepresent the arguments of the Chinese and reject them out of hand.

Foster criticized the leaders of the CPUSA for their “soft” line on U.S. imperialism, for supporting Kennedy in the ’60 elections and for tailing behind him thereafter. “What conceivable difference could it make to the American workers,” he asked, “whether Kennedy or Nixon was elected?” In a series of rhetorical questions, he asked: “What are the two main questions today? Peace and the Negro question, right? And what are they (the leaders of the CPUSA–Ed.) doing about either of these?” Fairly shouting the answer, he replied, “NOTHING”. When asked what he thought was the reason for this, he said, “They are all centrists.”

Some comrades ask, “If Foster had only been here, would he not perhaps have been able once again to save the CPUSA from revisionism?” Without detracting from Foster’s ability and achievements, the answer is, “No.” Despite all that Foster and others did, the CPUSA was never able to recover from the paralyzing and devitalizing poison of Browderism–it was never really “saved” from Browderism or from Gatesism and no force on earth could have “saved” it from Khrushchevism. Under Browder’s revisionist leadership, it lost its revolutionary spirit and purpose; though it formally “broke” with Browderism, its lack of a Marxist-Leninist equilibrium was shown by its erratic swerve into left-sectarianism, followed by its succumbing to Gatesism, and now its total capitulation to modern-day revisionism.

The record of the past four decades shows that American socialists have generally underestimated and fallen victim to the danger of right opportunism and revisionism, also that the measures taken to combat this danger have been inadequate, superficial and temporary. Instead of thorough-going intraparty discussion with criticism and self-criticism and a proletarianization of cadres, there has been a one-sided reliance on “quickie” methods – expulsions and the issuance of new orders for an “about face” – with the result that revisionism has been succeeded by left-sectarianism only to give way to revisionism again. Both of these are, after all, only opposite sides of the same coin, the same petty bourgeois ideology, which is notoriously unstable and subject to sudden vacillations. With monotonous regularity, the blame for these swings from left-to-right and right-to-left has been put on “objective conditions” and while it is true that revisionism tends to flourish when the ruling class puts on its velvet gloves and left-sectarianism to develop when the mailed fist is bared, objective conditions are not the sole cause. Internal, subjective factors which stem from an incorrect theory must also be taken into account.

The forces of the vanguard party must understand and learn to deal correctly with the class struggle in its ever-present dual nature: first, to maintain at all times an independent revolutionary line and role based on fundamental Marxist-Leninist principles which are never subject to compromise and, second, to engage in joint (united front) work with allies on particular issues in which compromising on specific questions is not only permissible but usually vital and necessary. Only if this duality of the struggle is grasped and the correct tactics mastered can the twin dangers of opportunism and revisionism on the one hand and sectarianism and adventurism on the other (the swinging pendulum pattern) be avoided. The key here is that the interrelationship of the two aspects must be properly gauged and dealt with at the same time even though in different degrees – not by dealing with one and ignoring the other and then committing the same error in reverse.

Though some hard lessons have been learned and some headway has been made, American socialists realize that the task of applying Marxist-Leninist principles to the specific conditions of the United States is still a long way from fulfillment. This task will be made easier if we learn how to properly deal with ideological contradictions and instead of regarding every such contradiction as an antagonism, can utilize the experiences gained in correctly resolving these contradictions (not ignoring or denying or trying to reconcile them without struggle) to improve the ideological development of our movement. A quotation from Lenin that Foster often cited was that: “Without correct theory there can be no revolution, no socialism.”

[1] Foster, History of the Communist Party in the U.S., Int’l Publishers, 1952, P.549.

[2] Lenin, Against Revisionism, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1959, p. 118.

[3] Foster, From Bryan to Stalin, Int’l Publishers, 1937, pp. 47-48.

[4] Foster, History of the C.P. of the U.S., p. 422.

[5] Browder, Teheran, Int’l Pub., 1944, p. 44.

[5a] Here, too, Foster bears a share of responsibility in not strongly opposing the line which put lop-sided emphasis on the united front (then represented by the Progressive Party movement) and failing to give adequate attention to the longer-range and primary need for developing an independent Marxist-Leninist position and thus building a proletarian party.

[6] Gates, Time for a Change, Political Affairs, Nov. 1956.

[7] Foster, On the Situation in the C.P., Political Affairs, Oct. 1956.

[8] Lenin, Against Revisionism, Foreign Languages Publishing House, Moscow, 1959, p. 345.

[9] Foster, In Defense of the C.P. and the Indicted Leaders, 1949 p. 21.

[10] Foster, History of the C.P. of the U.S., p. 252.