Rise of the working class

Rise of the working class Rise of the working class

Rise of the working class

Source: Labor College lecture

First published: Labor College Review, 1989

Transcription, mark-up: Steve Painter

By 1900 the division of the world among the European colonising powers was almost complete. Britain controlled 11,600,000 square miles with 345,000,000 people under its control.

Instead of the old, and now vanishing, industrial monopoly we find Britain with a colonial monopoly. British state power was extended over vast background regions for the purpose not so much that finished articles of consumption could be exported, but rather the export of the means of production and of capital.

The age of imperialism had arrived and it was Lenin who gave the classic definition of this imperialism.

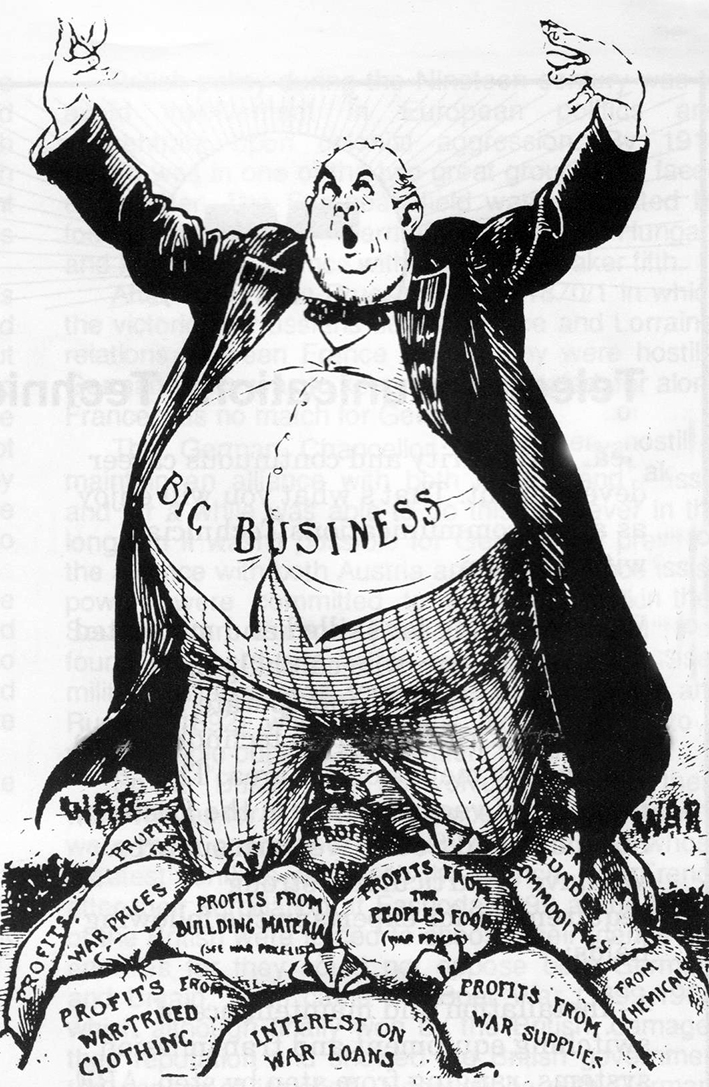

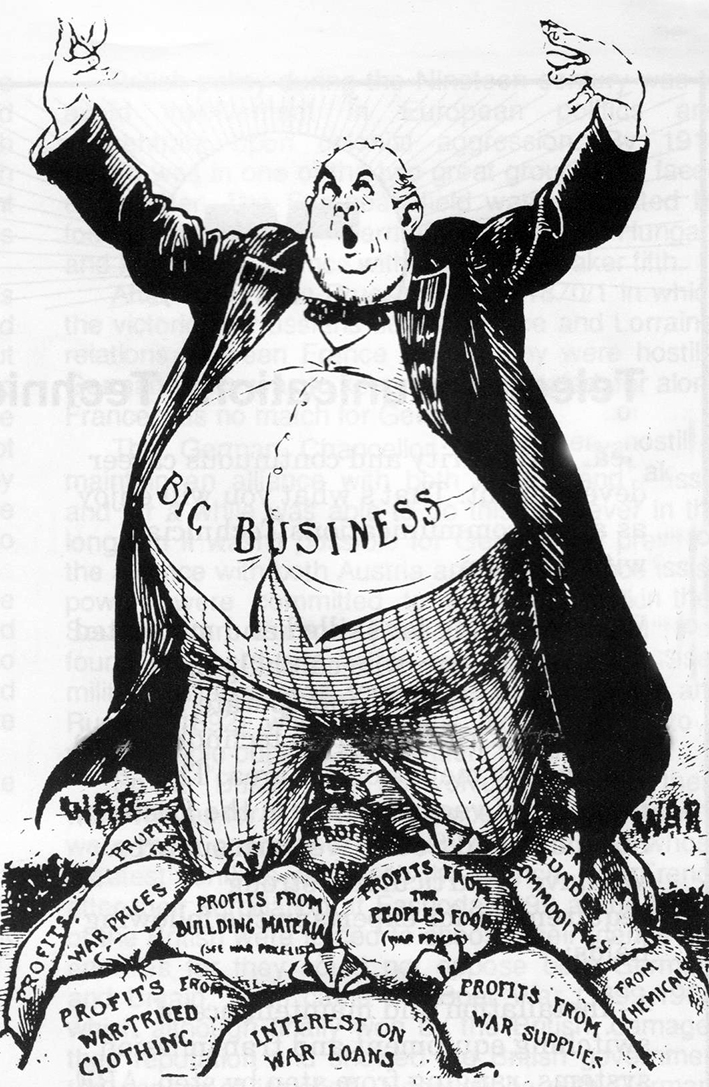

Firstly the concentration of production and capital to the extent that monopolies play a decisive role in economic life. In Britain by the end of the nineteenth century there were near-monopolies in iron and steel, shipping, ship building, soap, margarine, railways, banks and chemicals. The movement towards monopoly was less pronounced in the older export industries such as coal and mining. They remained out of date both in capital and method and they were in competition with rival industries of Germany and the United States.

Secondly the merging of bank capital with industrial capital.

Thirdly and perhaps most importantly was the exporting of capital in the form of loans and investments. The export of capital was linked with territorial expansion both as cause and effect. British loans and investments as in Egypt provided excuses for annexation and once this had been achieved British state power was used as a means of furthering the monopoly interests of the London bondholders.

Fourthly, international monopoly combines of capitalists divide up the world, and last, the territorial division of the world by the greatest capitalist powers is completed — this was substantially true by about 1900. From this date the export of capital increased rapidly so that by 1914 British investments and the income derived from them were double the 1900 figures.

Whereas Britain began with territorial expansion and the export of capital and only later passed on to the monopoly stage, the US with a vast area in which to expand began with an internal monopoly (for example Standard Oil, 1882) and only later began to appear as a colonial power and an exporter of capital after the war with Spain in 1898.

Germany had no such vast domains in which to expand, nor colonies. She set out to attack the world market by regimenting home industry with heavy involvement by the state.

Meanwhile Britain had fallen behind in productive techniques, relying on out-of-date plant and machinery. Only a thorough reconstruction of British industry would have allowed Britain to compete with Germany and the US, but while foreign investment offered super-profits there was no chance of this reconstruction taking place.

As a result, Britain lost ground to her newer rivals in the world’s markets. Until 1900 the French had been the major colonial competitor with Britain but after 1900 the main rival became Germany, which began to penetrate what the British considered to be their markets. By 1900 Britain and France had got the richest colonial booty while latecomers Germany and Italy had to be content with the less-desirable leftovers. In the east, Japan and Russia prepared to do battle over Korea.

Things could not remain as before. In the Balkans, not strictly colonies, German trade increased from 18.1 per cent to 29.3 per cent, while Britain fell from 24 per cent to 14.9 per cent. In South America the same trend occurred and even within the British empire the Germans were gaining at the expense of the British.

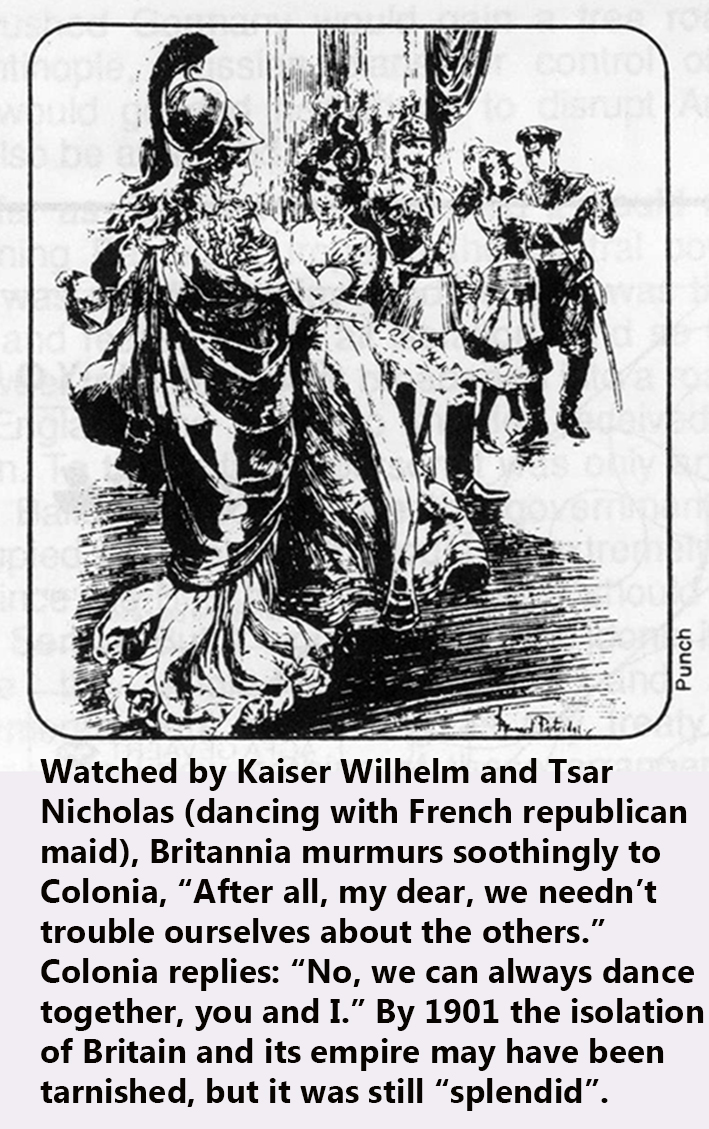

As there was no unappropriated territory left, the redivision of the world could only be effected by war. British policy during the nineteen century was to avoid involvement in European politics and concentrate upon colonial aggression. By 1914 Britain was in one of the two great groups that faced each other. The European field was dominated by four great powers: Germany and Austria-Hungary and Russia and France, with Italy as a weaker fifth.

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, in which the victorious Prussians seized Alsace and Lorraine, relations between France and Germany were hostile. German policy was to keep France

isolated, for alone France was no match for Germany.

After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, in which the victorious Prussians seized Alsace and Lorraine, relations between France and Germany were hostile. German policy was to keep France

isolated, for alone France was no match for Germany.

The German chancellor, Bismarck, wanted to maintain an alliance with both Austria and Russia and for a while was able to do this. However ,in the long run it wasn’t possible for Germany to preserve the alliance with both Austria and Russia since these powers were committed to conflicting policies in south-eastern Europe. Even Bismarck would have found this hard, and within two years of his fall a military alliance was formed between France and Russia (1892) while Germany moved closer to a more reliable but less independent ally in Austria.

So far Britain was uninvolved, although there were moves for a German alliance by the Tories, who were most concerned with the colonies, and whose greatest conflicts were with the French. The French after their humiliation at Fashoda 1899 at the hands of the British were forced to choose their friends and enemies for they could not oppose both Germany and Britain. Then came the Boer War (1899-1902), which although finally won by the British, damaged their reputation and showed the British government the danger of isolation. Negotiations with Germany were abortive and the way was clear for a British alliance with France. This alliance was concluded over the body of a colonial victim, Morocco, where prospectors had found indications of valuable minerals. This was too ripe a plum not to be picked by one of the colonial powers and in 1904 France recognised the “special interests” of Britain in Egypt while Britain in perfect diplomatic doubletalk promised France a free hand in Morocco.

What this actually meant became clear in 1911 when France, having discovered or created disorder, marched in and seized the Moroccan capital. Germany then demanded compensation in the French Congo. The British, through one-time pacifist Lloyd George, threatened war in support of the French. A compromise gave the Germans a small slice of the Congo.

Even before the Anglo-French entente had developed, relations between Germany and Britain had been growing hostile. From 1895 this was seen in a fierce naval race. In 1904 Lord Fisher, an extreme jingoist, was appointed First Sea Lord. Fisher privately urged that the German navy be surprised and destroyed, which when leaked did nothing to dispel German suspicions of the aggressive nature of the British. In 1906 the British developed the Dreadnought, a battleship that rendered previous battleships scrap iron. The government wanted to build four of these a year and by 1909, with a slogan of: "We want eight and we won't wait", there began a scare campaign of German naval construction and proposed invasion, which was created partly by the agents of certain armament firms and partly by the gutter press, particularly the Daily Mail. As a result, Britain’s naval budget was increased and the people were being psychologically prepared for the war on both sides of the Atlantic.

But this was not all. Since 1905 the British had been secretly committed to military support of France, although this was unknown even to the majority of cabinet. It was not impossible for Britain to remain outside any conflict between Germany and France. This was a striking example of the operations of a capitalist state that is able to function independently of the “democratic” institution.

An understanding between Russia and Britain took longer. A long-standing antagonism existed in Asia and in 1902 Britain had concluded an alliance with Japan. During the Russo-Japan war of 1904-05 relations with Russia became strained but Japan’s victory in fact made a rapprochement easier. Britain had a strong Asian ally that reinforced her position in Asia, and a weakened Russia was more anxious to find allies. A British loan to the Tsarist government gave it the means to stamp out the 1905 Revolution.

An Anglo-Russian entente was conducted in 1907. Edward, the British king, was the perfect monarch for the era of monopoly capitalism. His French leanings — was it because it was a centre of pleasure in Paris or a centre of money lending?

As Brigadier General Wingfield-Stratford wrote: “It would be difficult to compute what Edward owed to the friendships of Sir Ernest Cassel, but such a computation, if made, would be most suitably recorded on cash ruled paper.”

The entente with Russia needed a sacrificial lamb and Persia was to be the unfortunate victim. A treaty of 1907 was signed in which Britain and Russia guaranteed the independence and integrity of Persia. It was divided into three zones. Britain got the south-east, Russian the west and the rest was neutral. In a democratic revolution in 1909, the Persian shah was deposed and a measure of good government was introduced. Persia’s overlords were somewhat upset and a Russian army with British assistance restored the shah and European domination. Their aim as much as anything was to keep Germany out. Germany was attempting to stake out a claim in the Near East, which the decay of the Turkish empire had rendered a volatile domain. All the great powers except France had interests in the savage little states on the fringes of the Turkish Empire, and it was here that much imperialist rivalry centred.

Much time can be wasted debating whose “fault” led to the World War or the role of the “great” men of the day. The main fact still stands however, that for more than a decade Europe had been divided into rival imperialist groups, and while probably none of them wanted war, they could not achieve their objects without it, such is the nature of the imperialist monopoly stage of the capitalist development.

More precisely, however, the conflicts centred as follows:

Firstly, as already stated, there was the trade rivalry between Britain and Germany. Britain attempted to shut Germany out of the colonial and semi-colonial areas. The Germans countered by attempting to break through the British ring with a thrust to the south-east through the Balkans and Turkey.

Secondly, there was the German-French conflict. France had iron in abundance but no coal, while western Germany had coal but little iron. The industrialists of both powers wanted to unite the whole area under their own control.

Thirdly, Russia wanted to control the straits connecting the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, which conflicted with Germany’s eastward drive, while Russia’s influence in the Balkans was designed to disrupt the Austrian Empire with its large Slav and Romanian populations.

This situation was made more bitter by the pace at which land and naval rearmament was taking place. By 1913 it was clear to experts that war was close, if only because the various countries could not maintain growing armaments bills without a serious risk of bankruptcy.

We shouldn’t be surprised then, that any one of the disputes over Morocco in 1905-06 and 1911, Bosnia (1908); Tripoli (1911) (which Italy seized from a senile Turkey) or the Balkan War of 1912 could have led to wider war and was only resolved only to create new and deeper tensions.

The Balkans featured in Europe’s list of trouble spots, and it was in this area that the immediate cause of the war must be sought.

Firstly it was in the path of Germany’s eastern drive, in particular the Berlin-to-Baghdad railway, which would ensure the dependency of Turkey, where there was an increasing German presence. This route, it was felt, would ultimately threaten both British and Russian positions in Persia and India. The route passed through Serbia, but as long as Serbia was under Russian control a vital link for the Germans was missing. At the same time, the Russians used Serbia as a means of disrupting the Austrian Empire.

First the Russian party in Serbia killed the pro-Austrian king, which was followed by an economic war between Austria and Serbia. In 1908 Austria seized control of Bosnia. Russia was forced to consent when Germany and Austria threatened war. When Italy seized Tripoli in 1911, revealing how weak Turkey really was, the Russians organised an alliance of the Balkan states, which sought to reconquer the remaining Turkish provinces with the eventual aim of turning them against Austria.

After a short war, the Balkan allies were victorious. Serbia proposed to take the northern part of Albania, and Bulgaria was given most of Macedonia. Austria intervened and insisted on an independent Albanian state (1913). Serbia now wanted a slice of Macedonia as compensation — a demand that Austria encouraged Bulgaria to resist. A second war took place, which Bulgaria lost.

As a result, we find a new Balkan grouping. Serbia remained a creature of Russia, while Turkey and Bulgaria drew close to Germany and Austria (the Central Powers). In 1913 the Germans began to reorganise the Turkish army and began to pose as the protector of Moslem people. This, of course, was embarrassing to Britain, which had millions of Moslem subjects in India and Africa.

Serbia, with Russian support, began to prepare for the seizure of Bosnia (still under Austrian patronage). This was to be done by an armed uprising within Bosnia supported by an invasion. The Serbian prime minister declared at the Bucharest Conference after the second Balkan War:

The first game is won now we must prepare for the second, against Austria.

A campaign of terrorism was launched in which a number of Austrian officials were murdered, culminating in the shooting of Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne, on June 28, 1914. There

seems little doubt that the Serbian authorities knew of the plot and the Austrians welcomed it as a chance to settle accounts with Serbia. Only when seen in context of a whole series of Balkan

incidents does Austria’s impossible ultimatum to Serbia, which would have made it an Austrian protectorate, become understandable.

A campaign of terrorism was launched in which a number of Austrian officials were murdered, culminating in the shooting of Archduke Ferdinand, heir to the Austrian throne, on June 28, 1914. There

seems little doubt that the Serbian authorities knew of the plot and the Austrians welcomed it as a chance to settle accounts with Serbia. Only when seen in context of a whole series of Balkan

incidents does Austria’s impossible ultimatum to Serbia, which would have made it an Austrian protectorate, become understandable.

Russia’s position was clear enough, if Serbia were crushed, Germany would gain a free road to Constantinople, Russian plans for control of the straits would go, and her efforts to disrupt Austria would also be at an end.

So far as Russia was concerned, it would mean abandoning Eastern Europe to the central powers. France was not directly involved but she was tied to Russia and feared isolation above all. And so like a gunpowder trail the conflict flared.

In England the Sarajevo murder received little attention. To the ordinary person it was only another savage Balkan episode, while the government was preoccupied with Ireland. It would be extremely hard to convince the British people that they should go to war for Serbia. But it would have to be done if only because the Anglo-French military and naval arrangements were as binding as any treaty. The British people knew nothing of these arrangements and they were kept in the dark until the last moment.

On June 11, 1914, Sir Edward Grey, the foreign secretary, solemnly lied in the following terms:

If war arose between European powers there were no unpublished agreements which would restrict or hamper the freedom of the government or of parliament to decide whether or not Great Britain should participate in a war. That remains as true today as it was a year ago. No such negotiations are in progress and none are likely to be entered upon so far as I can judge.

In fact, Grey knew that Britain was pledged to protect the north coast of France from naval attack.

What was more likely to cause war was the fact that Germany was allowed to believe that Britain might remain neutral. But whatever might have happened, Russia and Austria were determined on war. Russia mobilised on July 31, Germany and France on August 1.

In England the great mass of working class and liberal opinion was in favour of peace but the government had made its choice and on August 2 Grey promised naval protection for the French coast and shipping.

The German invasion of Belgium came as a godsend.

Now the British government could disguise a war of imperialist robbery as a war for upholding treaty rights and the defence of small nations. There was much talk of “gallant little Belgium” and even some reflected sympathy was attempted for Serbia. In fact, the treaty guaranteeing Belgian neutrality (1839) had long since become obsolete. For years French, Belgian and British staff had been drawing up plans expecting that France and Belgium would form a single battlefield. Plans had been laid for landing British troops on the Belgian coast and probably these would have been landed by the end of August.

All this was hidden from the British people when the British sent the Germans an ultimatum to withdraw German troops from Belgium. No reply was received by midnight and the first imperialist world war had begun.