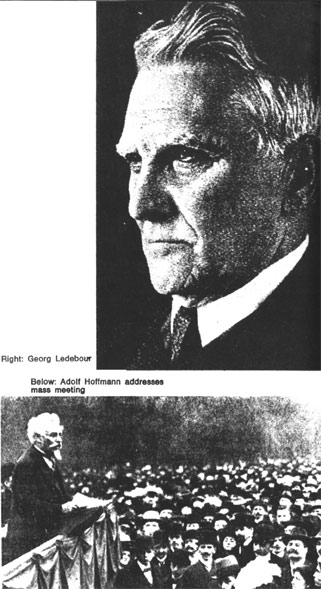

DURING the first two days after my arrival in Berne for the Zimmerwald conference I met all the members of the German delegation which had arrived for the International Socialist Conference. There were ten of them including three Reichstag deputies and one deputy from the Prussian Landtag. At the head of the delegation in age and popularity stood Georg Ledebour. He was just the same as ever: events of the war had left no visible stamp on him. During seven years living in Vienna I had to visit Berlin quite often and nearly every time I met Ledebour: either in the Reichstag, at Kautsky’s house or at the Furstenhof Café where Ledebour would hobble up the stairs on his stunted leg. Ledebour regarded himself a friend of the Russians and Poles and they called him sometimes Ledeburov, sometimes Ledeburg. However, his links with Russia and Poland never went beyond the bounds of purely parliamentary interests or personal services to Russian exiles at a time when his young friend Karl Liebknecht had succeeded in the course of the last decade in linking himself to young Russia by firm spiritual bonds. Ledebour must now be at least 65 as I recall that in 1910 or 1911 his 60th birthday was celebrated at Kautsky’s flat. August Bebel who had then already entered his 80s was there too. This was a period when the party had reached its zenith. Its organization, press and funds had attained an unprecedented flowering. Tactical unity seemed more complete than it had ever before. The old men automatically noted the successes and looked to the future without fear. The cause of this celebration, Ledebour, sketched caricatures at the dinner table and met with general acclaim. Without doubt he had the talent of a caricaturist – in general, irony and gall formed a component part of his temperament which in days gone by would have been regarded as choleric in the extreme. Five years have passed since that festive banquet of greying men – what great changes this period has brought and what even more colossal ones it carries in its womb! ...

Ledebour came over to Social-Democracy with Franz Mehring from the ranks of democratic journalism, but in the workers’ party he was incomparably more active in the capacity of parliamentarian than of journalist. In parliament Ledebour frequently created great sensations; on those occasions when he did not need to tie himself to the considerations of “high” policy but instead, giving way to his natural bile, attacked and lashed his adversary. He often provoked indignant shouts from the audience; the liberals hated him perhaps more than the conservatives, and he paid them back with sarcasms hurled with a grimace of contempt on his thin face, clean shaven and agile like an actor’s.

Adolf Hoffmann, also one of the old men, had changed little too with a beautiful shock of fine grey gossamer on his head and his Rochefortesque features. Hoffmann, a senior member of the Reichstag, fell at the last elections and remained only a member of the Prussian Landtag where he continued, hand in hand with Liebknecht, his fight against “Prussiary” i.e. the dominance of feudalism. Hoffmann was always numbered among the extreme left. Many years ago he drew up the ten commandments of the social-democrat and from that time onwards the nickname caught on to him of “Zehngebote-Hoffmann,’ (Ten-commandments Hoffmann). He is an orator of the people, with his cutting voice, sharp gestures and abundant store of jokes and jibes which frequently strike home very painfully. He holds the conviction that the honest democrat must before moving into a campaign against foreign “militarism” defeat reaction in his own country. Hoffmann is now more radical than Ledebour and is extremely dissatisfied with the fact that the opposition section of the Social-Democrat faction in the Reichstag abstained on the voting of war credits instead of voting openly against.

Relations in the party between the “patriotic” majority and the left wing have sharpened to the extreme. This is now no longer a theoretical nor a secondary tactical disagreement but a complete opposition in regard to the basic fact by which mankind is now living or rather swallowed up. There are no measures to which the Siidekums and Scheidemanns will not resort to gag their opponents’ mouths. And the more they lose the ground under their feet in the masses, the more they are forced to lean on the state apparatus and the more violent conflicts within the party will become ... Ledebour told of the Reichstag session when he protested against the repressive measures by the German military authorities against the civilian population. Scheidemann as is known, at that time disowned Ledebour.

“But do you think,” says Ledebour, “that these people would call a session of our faction to judge and condemn me? Nothing of the sort! During the ‘sensation’ which my words caused in Parliament, Scheidemann merely went up to the government table, had a whisper with the ministers – not with the faction but with the ministers! – and declared amid the general applause of the Reichstag that I was not authorized to criticize the actions of the military authorities. Such are the methods of these characters!”

“And still you decided not to vote openly against them in the Reichstag!” exclaimed another German delegate, an extreme Left, from his corner.

An argument about tactics started; Ledebour attempted to prove that the tactic of abstention being more cautious and not producing an open infringement of discipline would easily win over the majority of the faction. “At the begining of the war we were 14, now we are 36.”

“But you forget,” Hoffmann objected, “about the impression your conduct will have on the masses. Half-measures and half-decisions may be bad at any time but in the face of those events on which the future of our political development depends for many years, they are utterly impermissible. The masses are demanding clear, frank and courageous answers, for or against the war. And they must be given this answer.”

Unfortunately I cannot give the names of the other members of the delegation as this would be to expose them to the attacks of the German police. As regards Ledebour and Hoffmann they “expose” themselves fully appreciating the consequences, having put their names to the manifesto formulated by the Zimmerwald conference. But the rest of the German delegation have remained and must remain nameless; one can characterize them in only general terms.

In the delegation representing the left section of official German Social-Democracy there was in turn its own left wing. In Germany two publications gave ideological expression to these tendencies: Julius Borchart’s little propagandist bulletin Lichtstrahlen (Rays of light), which was formally very uncompromising but in effect very restrained and had little political influence, and Die Internationale, the organ of Luxemburg and Mehring, which in fact was not an organ but one issue in all, militant and lucid, after which the journal was closed down. Around the Internationale group were such influential elements of the German Left as Liebknecht and Zetkin. No less than three delegates were supporters of the Luxemburg-Mehring group. One supported Lichtstrahlen. Out of the remaining delegates two Reichstag deputies were by and large backers of Ledebour, two others possessed no definite psysiognomy. Hoffmann as we have said is an “extreme” left but he is a man of the old cast and the younger generation of Lefts are seeking new paths.

Kievskaya Mysl, No. 296, October 25, 1915

Last updated on: 10.4.2007