NATURE had given him a fiery, inextinguishable temperament and the sacred ability to rebel again and again, to love, to hate and to curse. Birth had given him a vital and never weakening bond with the suffering and struggling masses. The party had given him an understanding of the conditions for the liberation of the proletariat. All this taken together formed this magnificent personality, well-known and cherished, but now mourned, far beyond the limits of Vienna and Austria.

The working class needs leaders of different casts of character. Such leaders as those sons of the bourgeois classes who have broken their old social fetters, rebuilt themselves internally and who have identified the meaning of their life with the movement and growth of the working class play a great role in the history of the working class. First came the great Utopians: Saint-Simon, Fourier, and Owen; then the founders of scientific socialism: Marx, Engels and Lassalle all of whom had sprung from the bourgeois classes. How could one conceive of our German party and its development without Wilhelm Liebknecht and without Singer? Or without Kautsky? Of Austrian Social-Democracy without Victor Adler? Of French socialism without Lafargue, Jaurès and Guesde? And of Russian Social-Democracy without Plekhanov?

Through these brilliant dissidents the possessing classes return willy-nilly to the proletariat a particle of that scientific culture which through the efforts of centuries they had amassed amid the gloom of the oppressed popular masses.

And the proletariat can be proud that its historical mission like a mighty magnet attracts to itself noble minds and powerful characters from out of the propertied classes. But as long as the leadership of the political struggle lies only in the hands of these figures the workers cannot get away from the feeling that they are still under a political tutelage. Confident self-consciousness and class pride can fully penetrate them only when into the first rank of leaders they put forward their own people who have grown up with them and who embody in their personalities all the political and spiritual conquests of the working class. The proletariat can then look into such leaders as into a mirror where it can see the best sides of its own class “self”.

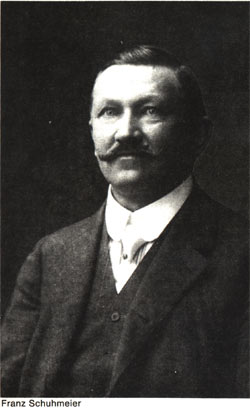

For the Vienna proletariat, as far as I can judge from five years observation, Franz Schuhmeier was above all such a class mirror.

Only very rarely did I come to meet Schuhmeier on a personal footing. But more than once I heard him at mass meetings, in parliament and at party congresses. It was enough to see and hear Schuhmeier several times to know him. For he least of all resembled a “riddle”, a person wrapped in himself. He was a man of action, skirmishes, appeals, of the streets and of impetus: in himself he was the embodiment of action and it was in action that he revealed himself. Of him one could say in the words of the Greek philosopher that he “carried his all with him”. That is why when we listened to him we not only heard his thought arrayed in living words which were always pointed and always his own but we would see all Schuhmeier in action in an athletic contest for the soul of his audience.

When you imagine to yourself standing behind the back of this splendid figure made of energy and daring that other miserable dark figure of the “Christian-Social” murderer with a Browning in his hand, the tragic sense of what has happened shakes you from head to foot.

We shall leave aside the question of what immediate motives guided the murderer. But who this unfortunate was, not as an individual but as a type we do know: he was a proletarian, but a renegade, a class defector. He did not want to join his class along its great historical road. It was amongst historically hostile forces, the state, the church and capital, whose existence is erected upon the physical enslavement and spiritual stultification of the masses that the murderer sought allies against his class when the latter was striving to impose its collective discipline upon him. Archaic prejudices which surround the cradle of the proletariat, the instincts of servility and miserable egoism meet together in this renegade – he personifies all the worst in the past of the labouring masses just as Schuhmeier personifies the best features of their future. And so the dark slavish past rises up in a wild frenzy against the future.

Who knows? Perhaps even in this miscreant there lived a festering inner wound, and a consciousness of apostasy, and this self-contempt turned into blind hate and mortal envy for everything that is lofty and fine in the socialist movement – for its contempt for all inherited superstitions, for its freedom from all servile instincts, for its moral courage and for its buoyant confidence of victory. And wild hate discharged the Browning.

What the guardians of law and order will now do with the murderer, who of course also considered himself a man of law and order, makes in the final analysis no difference to us. Along that path we will find no moral satisfaction. We shall leave the dead to bury this corpse.

But Franz Schuhmeier remains with us. We shall bury only what was mortal in him. For his spirit lives on in our hearts – the irreconcilable spirit of the tribune of revolution.

Luch, No.32, February 8, 1913

Last updated on: 23.4.2007