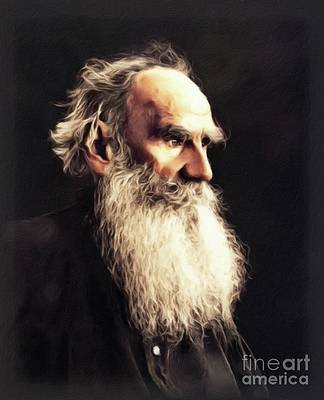

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1900

Source: From RevoltLib.com

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

The Anarchists are right in everything; in the negation of the existing order, and in the assertion that, without authority, there could not be worse violence than that of authority under existing conditions. They are mistaken only in thinking that Anarchy can be instituted by a revolution. "To establish Anarchy." "Anarchy will be instituted." But it will be instituted only by there being more and more people who do not require protection from governmental power, and by there being more and more people who will be ashamed of applying this power.

"The capitalistic organization will pass into the hands of workers, and then there will be no more oppression of these workers, and no unequal distribution of earnings."

"But who will establish the works; who will administer them?"

"It will go on of its own accord; the workmen themselves will arrange everything."

"But the capitalistic organization was established just because, for every practical affair, there is need for administrators furnished with power. If there be work there will be leadership, administrators with power. And when there is power there will be abuse of it—the very thing against which you are now striving."

.....

To the question, how to be without a State, without courts, armies, so on, an answer cannot be given, because the question is badly formulated. The problem is not how to arrange a State after the pattern of to-day, or after a new pattern. Neither I, nor any of us, is appointed to settle that question.

But, though voluntarily, yet inevitably must we answer the question. How shall I act in face of the problem which ever arises before me? Am I to submit my conscience to the acts taking place around me, am I to proclaim myself in agreement with the government, which hangs erring men, sends soldiers to murder, demoralizes nations with opium and spirits, and so on, or am I to submit my actions to conscience, i.e. not participate in government, the actions of which are contrary to my reason?

What will be the outcome of this, what kind of a government there will be,—of all this I know nothing; not that I don't wish to know; but that I cannot. I only know that nothing evil can result from my following the higher guidance of wisdom and love, or wise love, which is implanted in me; just as nothing evil comes of the bee following the instinct implanted in her, and flying out of the hive with the swarm, we should say, to ruin. But, I repeat, I do not wish to and cannot judge about this.

In this precisely consists the power of Christ's teaching and that not because, Christ is God or a great man, but because His teaching is irrefutable. The merit of His teaching consists in the fact that it transferred the matter from the domain of eternal doubt and conjecture on to the ground of certainty. "Thou art a man, a being rational and kind, and thou knowest that these qualities are the highest in thee; and, besides, thou knowest that to-day or to-morrow thou wilt die, disappear. If there be a God, then thou wilt go to Him, and He will ask of thee an account of thy actions, whether thou hast acted in accordance with His law, or, at least, with the higher qualities implanted in thee. If there be no God, thou regardest reason and love as the highest qualities, and must submit to them thy other inclinations, and not let them submit to thy animal nature—to the cares about the commodities of life, to the fear of annoyance, and material calamities."

The question is not, I repeat, which community will be the more secure, the better,—the one which is defended by arms, cannons, gallows, or the one that is not so safeguarded. But there is only one question for a man, and one it is impossible to evade: "Wilt thou, a rational and good being, having for a moment appeared in this world, and at any moment liable to disappear,—wilt thou take part in the murder of erring men or men of a different race, wilt thou participate in the exterminating of whole nations of so-called savages, wilt thou participate in the artificial deterioration of generations of men by means of opium and spirits for the sake of profit, wilt thou participate in all these actions, or even be in agreement with those who permit them, or wilt thou not?"

And there can be but one answer to this question for those to whom it has presented itself. As to what the outcome will be of it I don't know, because it is not given me to know. But what should be done I do unmistakably know.

And if you ask: "What will happen?" Then I reply that good will certainly happen; because, acting in the way indicated by reason and love, I am acting in accordance with the highest law known to me.

.....

The situation of the majority of men, enlightened by true brotherly enlightenment, at present crushed by the deceit and cunning of usurpers, who are forcing them to ruin their own lives—this situation is terrible, and appears hopeless.

Only two issues present themselves, and both are closed. One is to destroy violence by violence, by terrorism, dynamite bombs, and daggers, as Nihilist and Anarchists have attempted to do, to destroy this conspiracy of governments against nations, from without; the other is to come to an agreement with the government, making concessions to it, participating in it, in order gradually to disentangle the net which is binding the people, and to set them free. Both these issues are closed.

Dynamite and the dagger, as experience has already shown, only cause reaction, and destroy the most valuable power, the only one at our command, that of opinion.

The other issue is closed, because governments have already learned how far they may allow the participation of men wishing to reform them. They admit only that which does not infringe, which is non-essential; and they are very sensitive concerning things harmful to them,—sensitive because the matter concerns their own existence. They admit men who do not share their views, and who desire reform, not only in order to satisfy the demands of these men, but also in their own interest, in that of the government. These men are dangerous to the governments if they remain outside them and revolt against them,—opposing to the governments the only effective instrument the governments possess—public opinion; they must therefore render these men harmless, attracting them by means of concessions, in order to render them innocuous (like cultivated microbes), and then make them serve the aims of the governments, i.e. oppress and exploit the masses.

Both these issues being firmly closed and impregnable, what remains to be done?

To utilize violence is impossible; it would only cause reaction. To join the ranks of the government is also impossible—one would only become its instrument. One course, therefore, remains—to fight the government by means of thought, speech, actions, life, neither yielding to government nor joining its ranks and thereby increasing its power.

This alone is needed, will certainly be successful.

And this is the will of God, the teaching of Christ.

.....

We have now reached a stage when a man merely good and rational cannot participate in a State, i.e. in England (not to speak of our Russia), cannot be in agreement with landlordism, exploitation by manufacturers, capitalists, with the system in India, flogging, the opium trade, with the extermination of whole races in Africa, with wars and preparations for wars.

The ground upon which man says, "I don't know what the government is, nor why it exists, and I don't want to know; but I do know that I cannot live contrary to my conscience," this point of view is invincible, and to it the men of our time must adhere, in order to make life-progress. "I know what conscience dictates to me; as to you men, occupied with the State, organize the State as best you may, so that it correspond to the demands of the conscience of the men of our time."

But men are abandoning this impregnable position, taking up the view of reforming, ameliorating the State functions; and, by so doing, they are losing their points of support, acknowledging the necessity for the State, and thus abandoning their unassailable position.