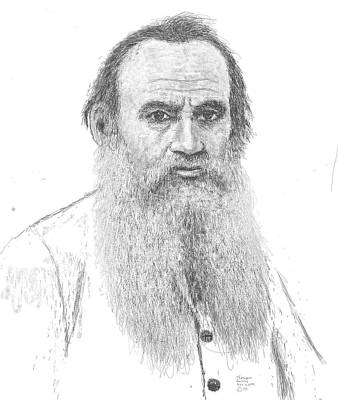

Leo Tolstoy Archive

Written: 1898

Source: Translated by Nathan Haskell Dole

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

A man sees with his eyes, hears with his ears, smells with his nose, tastes with his tongue, and feels with his fingers. Some men have more serviceable eyes. Some men have less serviceable eyes than others. One man has keen sense of hearing, another is deaf. One man has a more delicate sense of smell than another, and he perceives an odor from a long distance, while another will not notice the stench from a bad egg. One person recognizes an object by touching it, while another can do nothing of the sort, and is unable to distinguish wood from paper by the touch. One no sooner puts a substance into his mouth than he tells it is sweet, while another swallows it and cannot make out whether it is sweet or bitter.

In the same way wild animals have various senses in various degrees of power. But all wild animals have a keener scent than man has. When a man wants to tell what an object is, he examines it, he listens when it makes a noise, sometimes he smells of it and tastes it ; but more than all, if a man wants to be sure what an object is, he must feel of it.

But in the case of almost all wild animals, their chief dependence is on smelling the object. The horse, the wolf, the dog, the cow, the bear, do not recognize sub- stances until they test them by smelling.

When a horse is afraid of anything, it snorts ; in other words, it clears its nose so as to smell better, and its fear does not disappear until it has scented the object. A dog will often follow its master by its scent, and when it sees its master it is afraid, it does not recognize him, and it keeps on barking until it smells him, and recognizes that what seemed terrible to his eyes is really his master. Cattle see other cattle killed, they hear other cattle bellow in the abattoir, and yet they have no comprehension of what is taking place. But if the cow or the ox happens to find a place where the blood of cattle has been shed and catches the scent of it, then the creature understands, begins to low, kicks, and resists being driven from the place.

An old man had a sick wife ; he himself went to milk the cow. The cow lowed ; she knew it was not her mistress, and she would not give any milk. The man's wife 1 told him to wear her cloak and put her kerchief on his head ; and when he did so the cow let herself be milked. But when the old man threw off these garments, the cow smelt him and again held back her milk.

Hounds when they track a wild animal often run, not on the trail itself, but at one side, even as far as twenty paces. When an inexperienced huntsman wants to set his dog on the trail of an animal, and touches the dog's nose to the trail itself, the dog always goes to one side. The trail smells so strong to the dog that it cannot make the proper distinctions by the trail itself, and cannot tell whether the animal was running one way or the other. It goes to one side and then only it tells by its sense of smell in which direction the scent increases, and so runs after the animal.

It does what we do when any one speaks too loudly in our ear : we move away, and then at a proper dis- tance we distinguish what is said. Or when we are looking at any object which is too near us, we hold it farther from our eyes, and then we look at it.

Dogs recognize one another and communicate with one another by means of smells.

Still more delicate is the sense of smell in insects. The bee flies straight to the flower which it needs. The worm crawls to its leaf. The bug, the flea, the gnat, smell a man distant a hundred thousand times its own length away.

If the atoms emanating from substances and penetrat- ing our nostrils are minute, how infinitesimal must be the particles which affect the smellers of insects !

1 The khozya'ika.